A sunken Soviet nuclear submarine that’s been on the sea floor for three decades is leaking an abnormally high amount of radiation, according to the Institute for Marine Research. The institute says the leak poses no risk to people or fish.

The researchers took water samples near a ventilation duct on the Cold War-era sub. They contained up to 800,000 times the normal amount of the element caesium, a metal that can be radioactive.

“The levels we detected were clearly above what is normal in the oceans, but they weren’t alarmingly high,” expedition leader Hilde Elise Heldal said in a media release.

The scientists used a remote-operated vehicle called the Ægir 6000 to survey the wreck, which sits about a mile below the water surface.

Researchers have been monitoring the wreck for decades

After a fire in its engine room, the Komsomolets sank in April 1989, coming to rest on the sea floor about 135 miles southwest of Norway’s Bear Island.

Researchers have been monitoring the submarine since the 1990s, and have seen these types of radiation leaks from the sub’s ventilation duct before. But the most recent pictures of Komsomolets, taken in 2007, are twelve years old.

“Over the past few days we have also taken samples a few meters above the duct,” Justin Gwynn, a researcher at the Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority said. “We didn’t find any measurable levels of radioactive caesium there, unlike in the duct itself.”

They’re investigating a milky cloud

With the addition of a live video feed to their work, the scientists can gain new insights. They noticed a white-ish cloud rising up from the duct where they saw the high radiation levels.

Not every radiation reading was 800,000 times the normal ocean amount of caesium, so they’re investigating whether the milky cloud is related to the radiation readings.

They’ll keep monitoring the wreck of the Komsomolets. But they say there doesn’t seem to be any danger for the time being, because the radiation hasn’t cracked unsafe levels, the pollution is quickly diluted within the seawater, and there aren’t many fish that deep for fishermen to catch.

“We need good documentation of pollution levels in seawater, seabed sediments and, of course, fish and seafood,” Heldal said. “So we’ll continue monitoring both Komsomolets in particular and Norwegian waters in general.”

More Videos

View Video

View Video

February 2nd, 2026, 05:15 PM EST

WATCH LIVE: Jury returns guilty verdict in ‘au pair affair’ double murder trial

View Video

View Video

January 17th, 2026, 08:08 AM EST

WATCH LIVE: Spanberger becomes Virginia’s 1st woman governor during historic inauguration

View Video

View Video

November 25th, 2025, 12:14 PM EST

WATCH: Trump pardons turkeys Gobble and Waddle in annual Thanksgiving tradition

View Video

View Video

November 20th, 2025, 10:35 AM EST

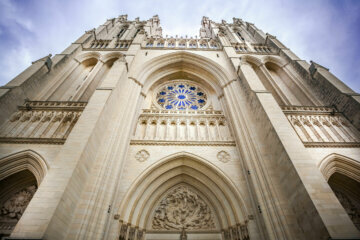

WATCH: Former Vice President Dick Cheney’s funeral service at Washington National Cathedral

View Video

View Video

November 12th, 2025, 03:09 PM EST

WATCH: Funeral services for conservationist Jane Goodall held in DC

View Video

View Video

November 4th, 2025, 10:18 PM EST

WATCH: Victory, concession as Virginia votes in general election

View Video

View Video

October 16th, 2025, 02:36 PM EDT

WATCH: Virginia attorney general candidates debate with text scandal front and center

View Video

View Video

September 18th, 2025, 06:14 PM EDT

WTOP Answers: Is the federal law enforcement surge decreasing crime in DC?

View Video

View Video

September 11th, 2025, 08:30 AM EDT

WATCH: Trump, military officials mark 24th anniversary of 9/11 attacks at the Pentagon

View Video

View Video

September 3rd, 2025, 01:40 PM EDT

WATCH: ICE raids create anxiety for teachers, parents, students in DC schools

View Video

View Video

September 2nd, 2025, 12:22 PM EDT

Game over? Zelky’s North arcade temporarily closes on Rehoboth boardwalk

View Video

View Video

August 4th, 2025, 10:35 AM EDT

WATCH: Panda Bao Li celebrates his 4th birthday at DC’s National Zoo

View Video

View Video

July 29th, 2025, 06:01 PM EDT

WATCH: Candidates for Gerry Connolly’s congressional seat face off in forum

View Video

View Video

July 3rd, 2025, 01:17 PM EDT

WATCH: Patriotic performances, dazzling fireworks mark America’s 249th birthday

View Video

View Video

May 6th, 2025, 04:31 PM EDT

WATCH: How AI is helping meteorologists with storm predictions

View Video

View Video

April 14th, 2025, 05:24 PM EDT

WATCH: Trophy falls apart as VP Vance tries to lift it during Ohio State’s White House visit

View Video

View Video

January 20th, 2025, 04:03 PM EST

WATCH: Speakers at Capital One’s indoor ‘parade’ mark Trump inauguration

View Video

View Video

January 16th, 2025, 04:44 AM EST

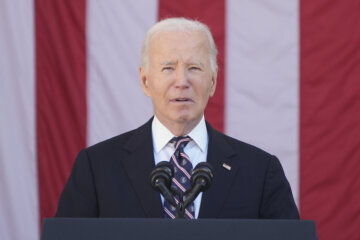

WATCH: President Biden delivers farewell address from Oval Office

View Video

View Video

January 7th, 2025, 04:08 PM EST

WATCH: Jimmy Carter’s remains lie in state at the Capitol ahead of state funeral

View Video

View Video

November 11th, 2024, 11:13 AM EST

WATCH: President Biden attends Veterans Day ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery

View Video

View Video

November 7th, 2024, 10:38 AM EST

WATCH: President Biden addresses nation after 2024 Election

View Video

View Video

October 10th, 2024, 04:55 PM EDT

WATCH: Hogan, Alsobrooks face off in only debate ahead of Maryland Senate vote

View Video

View Video

October 2nd, 2024, 06:48 AM EDT

WATCH: JD Vance, Tim Walz meet for one-and-only vice presidential debate

View Video

View Video

July 24th, 2024, 01:06 PM EDT

WATCH: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu delivers speech to Congress

View Video

View Video

July 23rd, 2024, 04:28 AM EDT

How Old Town Alexandria is preserving its original DC border

View Video

View Video

July 13th, 2024, 11:13 PM EDT

WATCH: Shots fired during Pa. rally as Secret Service escorts injured Trump off stage

View Video

View Video

July 11th, 2024, 05:54 AM EDT

Matt About Town: Unearthing hidden fossils from millions of years ago at a popular DC monument

View Video

View Video

June 11th, 2024, 06:15 AM EDT

Matt About Town: DC’s newest pop-up mixes nostalgia and mini golf

View Video

View Video

May 30th, 2024, 05:59 PM EDT

WATCH: Trump, Bragg react after guilty verdict in hush money trial

View Video

View Video

May 9th, 2024, 01:23 PM EDT

People on the National Mall celebrate their mom by sharing her best advice

View Video

View Video

May 9th, 2024, 05:38 AM EDT

Matt About Town: Loudoun Co. comic store hosts free comic book giveaway on Star Wars Day

View Video

View Video

March 14th, 2024, 05:01 AM EDT

Matt About Town: Dive into the conspiracy behind the disappearance of an obscure DC monument

View Video

View Video

February 8th, 2024, 05:22 AM EST

Ice Ice Baby: This obscure Alexandria monument celebrates all things frozen

View Video

View Video

January 30th, 2024, 12:50 PM EST

Embrace your inner codebreaker at Maryland’s National Cryptologic Museum

View Video

View Video

January 15th, 2024, 02:04 PM EST

WATCH: California woman finds large black bear in crawl space

View Video

View Video

December 14th, 2023, 07:45 AM EST

WATCH: There’s a ‘wine revolution’ happening in the DC area— and it’s not where you might expect

View Video

View Video

December 5th, 2023, 07:37 AM EST

WATCH: Acorns are surprisingly edible. New exhibit at GW champions the ‘humble little nut’

View Video

View Video

November 28th, 2023, 04:58 AM EST

WATCH: No pandas? No problem. DC’s National Zoo shines brighter than ever this season

View Video

View Video

November 21st, 2023, 04:54 AM EST

Explore DC’s FDR memorial … not the one you’re thinking of!

View Video

View Video

November 16th, 2023, 05:39 AM EST

Dessert for breakfast! Have you had the award-winning gelato at DC’s National Gallery of Art?

View Video

View Video

November 7th, 2023, 04:05 AM EST

WATCH: National Building Museum’s new ‘Mini Memories’ exhibit offers pocket-size fun for the whole family

View Video

View Video

November 2nd, 2023, 05:01 AM EDT

WATCH: Down, but never out: Last Montgomery Co. duckpin bowling lanes thrive after reopening in White Oak

View Video

View Video

October 26th, 2023, 04:53 AM EDT

WATCH: Md. cyclist looks to be first Black woman to compete for Team USA at 2028 Olympics

View Video

View Video

October 24th, 2023, 04:39 AM EDT

Out of town feel in the heart of DC: Hillwood Estate offers unique glimpse into the past of high society

View Video

View Video

October 20th, 2023, 05:10 AM EDT

WATCH: President Biden delivers Oval Office address on Israel, Ukraine

View Video

View Video

October 19th, 2023, 07:39 AM EDT

WATCH: Old Town Alexandria Colonial Ghost Tours offer spooky fun for all ages

View Video

View Video

August 30th, 2023, 11:49 AM EDT

WATCH LIVE: Hurricane Idalia steamed through the US after making landfall

View Video

View Video

July 27th, 2023, 10:34 AM EDT

Crowds watch Chincoteague wild ponies complete 98th annual swim in Virginia

View Video

View Video

June 15th, 2023, 01:21 PM EDT

WATCH: See the progress of the I-95 rebuild in Philadelphia

View Video

View Video

April 4th, 2023, 07:24 PM EDT

WATCH: Trump delivers remarks at Mar-a-Lago after New York hearing

View Video

View Video

March 29th, 2023, 07:19 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Reason to care about the 2023 Nationals and how a new Commanders owner impacts Lamar Jackson

View Video

View Video

March 23rd, 2023, 05:55 AM EDT

Van Leeuwen ice cream shop opens in Union Market with $1 scoops

View Video

View Video

March 14th, 2023, 05:51 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Breaking down the NCAA basketball brackets and Commanders free agency

View Video

View Video

March 8th, 2023, 05:56 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: The curious case of Lamar Jackson and what to expect from Terps’ tournament run

View Video

View Video

March 1st, 2023, 06:27 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Choosing the Commanders’ new veteran QB within our jam-packed, beautiful disaster

View Video

View Video

February 23rd, 2023, 05:56 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: What Eric Bieniemy’s offense will mean for the Commanders

View Video

View Video

February 16th, 2023, 05:34 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: The Commanders’ ongoing OC search and Strasburg’s future with the Nats

View Video

View Video

February 8th, 2023, 05:47 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Super Bowl LVII preview and the LeBron-Jordan GOAT debate

View Video

View Video

February 8th, 2023, 04:45 AM EST

VIDEO: Biden’s 2023 State of the Union address, Republican response

View Video

View Video

January 31st, 2023, 05:36 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Ranking Washington’s 1982 and 1987 Super Bowl teams on their milestone anniversaries

View Video

View Video

January 25th, 2023, 05:47 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Hoyas win, Wizards confound and the Commanders’ QB question — Brady or Rodgers?

View Video

View Video

January 18th, 2023, 06:09 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Who is the Commanders’ best OC option?

View Video

View Video

January 10th, 2023, 05:46 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: The truth about the 2022 Commanders how it will impact 2023

View Video

View Video

January 6th, 2023, 01:44 PM EST

WATCH: Biden marks second anniversary of Jan. 6 Capitol riot

View Video

View Video

January 5th, 2023, 05:26 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Assessing the Howell factor and whether Rivera is right for the Commanders

View Video

View Video

January 3rd, 2023, 08:12 AM EST

President Teddy Roosevelt’s teenage relative takes office in DC

View Video

View Video

December 29th, 2022, 05:06 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: How the Commanders’ QB change alters the rest of the 2022 season

View Video

View Video

December 26th, 2022, 10:23 AM EST

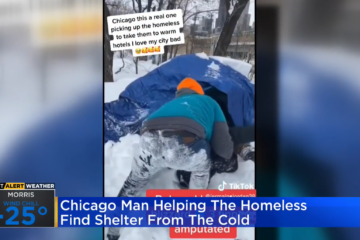

WATCH: Chicago man helps people experiencing homelessness during deadly cold

View Video

View Video

December 22nd, 2022, 10:24 AM EST

DC Sports Huddle: How the Commanders can pull off another season-saving upset in San Francisco

View Video

View Video

December 20th, 2022, 08:06 AM EST

WATCH: Horse rescued after falling through thin ice over frozen lake

View Video

View Video

December 8th, 2022, 07:33 AM EST

VIDEO: Walmart donation from Chesapeake store to help some at Christmas

View Video

View Video

December 7th, 2022, 06:10 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Commanders at the bye — and the last time they ruled DC sports

View Video

View Video

December 6th, 2022, 09:35 AM EST

WATCH: Officers receive Congressional Gold Medals for Jan. 6

View Video

View Video

December 2nd, 2022, 12:03 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: How Washington can take command of the NFC

View Video

View Video

November 22nd, 2022, 04:57 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Thanksgiving, the Commanders’ playoff push and a new ownership option

View Video

View Video

November 15th, 2022, 11:02 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Ranking Commanders’ upset win and whether it keeps Heinicke at QB

View Video

View Video

November 9th, 2022, 07:21 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Assessing the Commanders at midseason — can Washington stun Philly on MNF?

View Video

View Video

November 3rd, 2022, 06:00 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: The truth about a Snyder sale and the Commanders’ crucial stretch

View Video

View Video

November 2nd, 2022, 06:49 PM EDT

WATCH: Biden warns of threats to democracy from election deniers

View Video

View Video

October 27th, 2022, 05:39 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Have we seen the last of Carson Wentz as Commanders QB?

View Video

View Video

October 25th, 2022, 09:26 AM EDT

WATCH: Imported fire ants reported in Southeastern Virginia

View Video

View Video

October 25th, 2022, 09:24 AM EDT

WATCH: Towson baseball player with diabetes lands NIL deal

View Video

View Video

October 20th, 2022, 07:41 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Making sense of the Commanders’ QB conundrum and Snyder’s ownership strife

View Video

View Video

October 14th, 2022, 05:16 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Commanders win amid tumultuous day — here’s what it means for Washington

View Video

View Video

October 6th, 2022, 06:10 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: The harsh reality of the Washington Commanders

View Video

View Video

September 29th, 2022, 05:42 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: The Commanders’ reckoning in ‘Big D’ and Wizards’ mission in Japan

View Video

View Video

September 22nd, 2022, 05:59 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Can the Commanders defense be fixed in time?

View Video

View Video

September 22nd, 2022, 11:22 AM EDT

Dozens indicted in COVID-19 nutrition program fraud scheme

View Video

View Video

September 15th, 2022, 04:58 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Are the Commanders better as underdogs?

View Video

View Video

September 8th, 2022, 04:48 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Washington Commanders 2022 season preview, predictions

View Video

View Video

August 31st, 2022, 04:51 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Commanders’ cut to 53 and the big move that could make them contenders

View Video

View Video

August 25th, 2022, 05:23 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Does the Ravens’ preseason win streak matter? And what if Washington ends it?

View Video

View Video

August 18th, 2022, 04:08 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: The Commanders’ KC measuring stick and Mystics playoff preview

View Video

View Video

August 17th, 2022, 08:28 PM EDT

WATCH: Survivor of lightning strike near White House shares story

View Video

View Video

August 17th, 2022, 10:21 AM EDT

WTOP’s Old Bay-flavored snacks taste test: Which treat will win?

View Video

View Video

August 11th, 2022, 04:50 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Has the Commanders’ culture really changed?

View Video

View Video

August 3rd, 2022, 05:19 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Is Soto trade Washington’s ‘Curse of the Childish Bambino’?

View Video

View Video

August 1st, 2022, 06:37 PM EDT

WATCH: Biden speaks after US strike kills top al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahri

View Video

View Video

July 27th, 2022, 05:39 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Top storylines out of Commanders training camp

View Video

View Video

July 20th, 2022, 04:20 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Will the Nationals really trade Juan Soto?

View Video

View Video

July 18th, 2022, 08:48 AM EDT

Tasting the rainbow may be toxic: Lawsuit filed over Skittles’ use of chemical

View Video

View Video

July 6th, 2022, 03:45 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: What to expect from Terry McLaurin now that he’s paid

View Video

View Video

June 30th, 2022, 11:44 AM EDT

WATCH: Ketanji Brown Jackson sworn in as Supreme Court justice

View Video

View Video

June 29th, 2022, 04:23 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Which deal was bigger — Commanders re-signing McLaurin or Wizards trade?

View Video

View Video

June 25th, 2022, 06:20 PM EDT

Take a walk through DC history on the 112th birthday of Meridian Hill Park

View Video

View Video

June 24th, 2022, 11:59 PM EDT

WATCH: Biden delivers remarks following Supreme Court abortion ruling

View Video

View Video

June 22nd, 2022, 06:18 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: 2022 NBA draft preview — the Wizards’ best and worst picks

View Video

View Video

June 17th, 2022, 01:00 AM EDT

WATCH: Third Jan. 6 hearing turns to pressure on Pence to reject election

View Video

View Video

June 15th, 2022, 04:48 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Who more deserves big money — Terry McLaurin or Lamar Jackson?

View Video

View Video

June 8th, 2022, 05:45 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Did Jack Del Rio just cause a schism in the Commanders locker room?

View Video

View Video

June 1st, 2022, 06:13 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Chase’s return to Commanders camp and NBA Finals preview

View Video

View Video

June 1st, 2022, 02:44 PM EDT

Watch Live: Jury reaches verdict in Depp-Heard defamation trial

View Video

View Video

May 13th, 2022, 12:05 AM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Analyzing Washington Commanders’ schedule, Caps’ playoff hopes

View Video

View Video

May 2nd, 2022, 02:33 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Grading the Commanders’ draft and Capitals playoff preview

View Video

View Video

April 27th, 2022, 05:16 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Whom should the Commanders take in the NFL Draft?

View Video

View Video

April 21st, 2022, 08:40 AM EDT

WATCH: Biden announces new military assistance for Ukraine

View Video

View Video

April 20th, 2022, 06:04 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Commanders’ NFL draft strategy and best celebrity DC owners

View Video

View Video

April 13th, 2022, 05:23 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: How to get the Wizards back to NBA contention

View Video

View Video

April 6th, 2022, 05:23 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: What to expect from the 2022 Washington Nationals

View Video

View Video

April 5th, 2022, 06:22 PM EDT

WATCH: Fairfax Co. woman disappeared after ‘goodbye dinner’ with ex-boyfriend

View Video

View Video

March 24th, 2022, 08:28 AM EDT

WATCH: Day 4 of confirmation hearing for Supreme Court nominee Jackson

View Video

View Video

March 24th, 2022, 01:45 AM EDT

WATCH: Day 3 of confirmation hearing for Supreme Court nominee Jackson

View Video

View Video

March 23rd, 2022, 03:42 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Maryland’s move for Willard, NFL’s QB carousel

View Video

View Video

March 22nd, 2022, 09:30 PM EDT

WATCH: Day 2 of confirmation hearing for Supreme Court nominee Jackson

View Video

View Video

March 9th, 2022, 04:12 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Is Carson Wentz the right QB for the Commanders?

View Video

View Video

March 2nd, 2022, 05:27 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Part I of the Commanders QB question — is the answer in the NFL draft?

View Video

View Video

February 23rd, 2022, 06:16 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Handshakes, tanking and the Commanders’ new mascot

View Video

View Video

February 16th, 2022, 05:10 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Remembering the Ryan Zimmerman era in Washington

View Video

View Video

February 9th, 2022, 06:32 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: How Super Bowl LVI ties into Commanders’ rebuild

View Video

View Video

February 9th, 2022, 04:12 AM EST

Memorial service for 2 officers killed in Bridgewater College shooting

View Video

View Video

February 3rd, 2022, 10:13 AM EST

WATCH: House oversight roundtable on Washington football’s toxic workplace culture

View Video

View Video

February 2nd, 2022, 06:43 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: How does Washington Commanders sit with you?

View Video

View Video

February 2nd, 2022, 07:52 AM EST

WATCH: It’s Groundhog Day 2022 — will Phil see his shadow?

View Video

View Video

January 26th, 2022, 05:29 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Ranking Washington’s 1991 Super Bowl team

View Video

View Video

January 19th, 2022, 07:09 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Washington’s blueprint lies in the NFL playoffs

View Video

View Video

January 12th, 2022, 04:02 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Who should be Washington’s next starting QB?

View Video

View Video

January 6th, 2022, 04:57 PM EST

WATCH: Prayer vigil on Capitol steps commemorates Jan. 6 attack

View Video

View Video

January 5th, 2022, 06:40 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Washington’s name game and moral of its 2021 season

View Video

View Video

December 22nd, 2021, 02:54 PM EST

WATCH: White House COVID-19 response team provides situational update

View Video

View Video

December 22nd, 2021, 02:40 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Does Washington have a Christmas miracle in Dallas?

View Video

View Video

December 15th, 2021, 06:52 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Can Washington overcome COVID, Eagles in Philadelphia?

View Video

View Video

December 15th, 2021, 05:52 PM EST

WATCH: Washington National Cathedral honors 800,000 Americans who died of COVID-19

View Video

View Video

December 9th, 2021, 06:50 AM EST

WATCH: Santa arrives in Los Angeles by police helicopter

View Video

View Video

December 8th, 2021, 05:55 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Can Washington beat Dallas and steal back the NFC East?

View Video

View Video

December 3rd, 2021, 07:51 AM EST

WTOP’s Beer of the Week: Bluejacket/Finback For the Time Being DIPA

View Video

View Video

December 1st, 2021, 06:16 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: The reality of the Washington Football Team’s win streak

View Video

View Video

November 24th, 2021, 06:23 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Can Washington make another NFL playoff push?

View Video

View Video

November 17th, 2021, 06:59 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: Can the Washington Football Team contain Cam Newton?

View Video

View Video

November 10th, 2021, 06:39 PM EST

DC Sports Huddle: What to expect from Washington Football Team’s second half

View Video

View Video

November 3rd, 2021, 06:45 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: The state of the Washington Football Team at midseason

View Video

View Video

October 27th, 2021, 08:22 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Will Washington buy or sell at the NFL trade deadline?

View Video

View Video

October 13th, 2021, 05:44 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Caps preview and can Washington keep up with the Chiefs?

View Video

View Video

October 6th, 2021, 05:06 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Should Washington have drafted Justin Herbert?

View Video

View Video

September 29th, 2021, 02:31 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Why Washington’s defense needs Atlanta

View Video

View Video

September 22nd, 2021, 05:44 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Can Taylor Heinicke lead Washington to victory in Buffalo?

View Video

View Video

September 21st, 2021, 05:24 PM EDT

WATCH: DC couple shares first, last kiss at Dave Thomas Circle Wendy’s before restaurant closes

View Video

View Video

September 15th, 2021, 04:50 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Washington vs. Giants preview, WFT QB conundrum

View Video

View Video

September 13th, 2021, 10:48 AM EDT

VIDEO: WTOP tests out Helbiz’s DC historical tour on scooter

View Video

View Video

September 8th, 2021, 04:20 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: What will the Washington Football Team be in 2021?

View Video

View Video

September 7th, 2021, 09:30 PM EDT

Seeing stripes: Dazzle of zebras spotted in Prince George’s Co.

View Video

View Video

September 1st, 2021, 02:12 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Washington Football Team roster breakdown, college football preview

View Video

View Video

August 24th, 2021, 02:15 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Cause for concern over Washington Football Team offense?

View Video

View Video

August 17th, 2021, 12:33 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Washington Football Team’s preseason progress report

View Video

View Video

August 10th, 2021, 02:40 PM EDT

DC Sports Huddle: Washington Football Team ‘preseason superstars’

View Video

View Video

August 3rd, 2021, 02:01 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: Will COVID unravel the Washington Football Team?

View Video

View Video

July 27th, 2021, 03:06 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: Washington Football Team Training Camp Preview

View Video

View Video

July 20th, 2021, 01:08 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: Is Wes Unseld Jr. an inspired Wizards hire?

View Video

View Video

July 13th, 2021, 01:14 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: What should be the new name for the Washington Football Team?

View Video

View Video

July 6th, 2021, 01:56 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: NBA Finals preview, Scherzer’s All-Star snub

View Video

View Video

June 29th, 2021, 02:27 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: How far can Tiafoe, Kudla go at Wimbledon?

View Video

View Video

June 25th, 2021, 06:52 PM EDT

WATCH: Arlington man waiting for word on missing family members after Miami condo collapse

View Video

View Video

June 25th, 2021, 08:13 AM EDT

Japan’s Olympics superfans who want Tokyo 2020 to go ahead despite COVID-19

View Video

View Video

June 25th, 2021, 08:02 AM EDT

His wife died by suicide after a 13-month battle with long-haul Covid. He hopes help is on the way for others

View Video

View Video

June 25th, 2021, 07:46 AM EDT

Weddings are making a huge comeback and couples are ‘panic booking’

View Video

View Video

June 8th, 2021, 02:03 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: Who should be elected to a DC sports super team?

View Video

View Video

May 25th, 2021, 03:16 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: How do the Wizards win in Philly? Time for Caps rebuild?

View Video

View Video

May 11th, 2021, 02:00 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: Russell Westbrook’s legacy, impact on the Wizards

View Video

View Video

May 5th, 2021, 08:38 AM EDT

WATCH LIVE: Facebook Oversight Board announces Trump decision

View Video

View Video

May 5th, 2021, 06:35 AM EDT

DC police release more bodycam footage in shooting of Terrance Parker

View Video

View Video

May 4th, 2021, 02:21 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: Wizards are contenders, Washington’s NFL draft grades

View Video

View Video

April 27th, 2021, 03:29 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: Who Washington should pick in the NFL draft; inside Caps’, Wizards’ playoff pushes

View Video

View Video

April 21st, 2021, 09:31 AM EDT

Apple unveils a new iPad Pro, colorful iMacs, AirTag and more

View Video

View Video

April 20th, 2021, 02:36 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: The Wizards look playoff-ready and Alex Smith’s legacy

View Video

View Video

April 14th, 2021, 09:39 AM EDT

WATCH: Trial of Derek Chauvin, charged with George Floyd’s murder

View Video

View Video

April 13th, 2021, 02:36 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: Nats back on track; Caps, Wizards make playoff pushes

View Video

View Video

March 23rd, 2021, 03:41 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: Maryland March Madness and remembering Elgin Baylor

View Video

View Video

March 16th, 2021, 02:36 PM EDT

The WTOP Huddle: FitzMagic hits Washington, Hoyas become March Madness stars

View Video

View Video

March 11th, 2021, 09:05 PM EST

WATCH: President Biden addresses nation on anniversary of COVID-19 in US

View Video

View Video

March 9th, 2021, 02:08 PM EST

The WTOP Huddle: Scherff’s franchise tag, Washington’s next QB and March Madness

View Video

View Video

March 4th, 2021, 08:09 AM EST

WATCH LIVE: Outside Capitol amid possible plot to breach Congress

View Video

View Video

March 3rd, 2021, 09:31 AM EST

WATCH LIVE: National security officials testify before Joint Senate hearing on Capitol riot

View Video

View Video

March 2nd, 2021, 09:10 AM EST

WATCH: FBI Director Chris Wray testifies in Congress on Capitol riot

View Video

View Video

February 25th, 2021, 09:45 AM EST

WATCH LIVE: Acting Capitol Police chief testifying about Capitol riot

View Video

View Video

February 23rd, 2021, 02:38 PM EST

The WTOP Huddle: Wizards keep winning and a new Nats lineup?

View Video

View Video

February 22nd, 2021, 03:19 PM EST

This 29-year-old cancer survivor is set to be the youngest American ever in space

View Video

View Video

February 16th, 2021, 03:09 PM EST

The WTOP Huddle: Wall’s return to Washington and Nats Spring Training

View Video

View Video

February 10th, 2021, 07:45 PM EST

WATCH: Opening arguments in Donald Trump’s impeachment trial

View Video

View Video

February 3rd, 2021, 07:38 AM EST

WATCH: Members of Congress pay their respects to fallen Capitol Police officer

View Video

View Video

February 2nd, 2021, 09:25 PM EST

WATCH: Capitol Police officer Brian Sicknick lies in honor at Capitol Rotunda

View Video

View Video

February 2nd, 2021, 03:14 PM EST

The WTOP Huddle: Super Bowl LV and which QB can get Washington back to one?

View Video

View Video

January 26th, 2021, 03:13 PM EST

The WTOP Huddle: COVID’s current impact on sports, Stafford a QB option for Washington?

View Video

View Video

January 21st, 2021, 08:31 AM EST

WATCH LIVE: Presidential Inaugural Prayer Service at National Cathedral

View Video

View Video

January 20th, 2021, 11:00 PM EST

Joe Biden’s Inauguration Day concludes with extravagant firework show

View Video

View Video

January 19th, 2021, 03:47 PM EST

The WTOP Huddle: Hurney returns to Washington Football Team, will Watson be next?

View Video

View Video

January 12th, 2021, 02:58 PM EST

The WTOP Huddle: What’s next for the Washington Football Team?

View Video

View Video

January 12th, 2021, 08:51 AM EST

WATCH LIVE: House vote expected on 25th Amendment resolution

View Video

View Video

December 29th, 2020, 09:29 PM EST

WTOP Huddle: Washington Football Team parts ways with Dwayne Haskins

View Video

View Video

December 22nd, 2020, 08:56 PM EST

WTOP Huddle: How will Washington Football Team respond against Carolina?

View Video

View Video

December 18th, 2020, 09:17 AM EST

Here’s why some McDonald’s restaurants are putting cameras in their dumpsters

View Video

View Video

December 18th, 2020, 03:51 AM EST

‘We should be less afraid to be afraid,’ says Emily Harrington after historic El Capitan climb

View Video

View Video

December 17th, 2020, 07:27 AM EST

Here are some of the amazing things that happened on Zoom this year

View Video

View Video

December 16th, 2020, 02:07 AM EST

The WTOP Huddle: Washington Football Team now sits atop NFC East standings

View Video

View Video

December 14th, 2020, 07:29 PM EST

WATCH: President-elect Joe Biden on Electoral College confirmation

View Video

View Video

December 8th, 2020, 02:18 PM EST

The WTOP Huddle: Was Washington’s win in Pittsburgh a ‘culture-setting’ victory?

View Video

View Video

December 4th, 2020, 04:53 PM EST

Look out world! DC’s giant panda cub Xiao Qi Ji is on the move

View Video

View Video

December 1st, 2020, 04:52 PM EST

WTOP Huddle: After a statement win, where does the Washington Football Team stand?

View Video

View Video

December 1st, 2020, 04:32 PM EST

Instagram influencer Alexis Sharkey was found dead near a Houston interstate, police say

View Video

View Video

December 1st, 2020, 06:43 AM EST

Super Nintendo World is opening at Universal Studios Japan in February. Here’s a sneak peek

View Video

View Video

November 17th, 2020, 08:17 PM EST

WTOP Huddle: Is Alex Smith starting a good thing for the Washington Football Team?

View Video

View Video

November 16th, 2020, 07:18 PM EST

Astronauts really just took Baby Yoda with them up to space

View Video

View Video

November 10th, 2020, 09:21 PM EST

WTOP Huddle: Where does the Washington Football Team go from here?

View Video

View Video

November 6th, 2020, 11:19 AM EST

How to cope with stress eating through the 2020 election

View Video

View Video

November 2nd, 2020, 10:46 AM EST

Kendall Jenner slammed for Halloween 25th birthday celebration

View Video

View Video

October 28th, 2020, 08:52 AM EDT

Bugatti unveils a super light hypercar that can top 300 miles an hour

View Video

View Video

October 25th, 2020, 07:59 AM EDT

Dad’s Zoom Halloween costume for his daughter is scary good

View Video

View Video

October 22nd, 2020, 10:52 PM EDT

WATCH: Final presidential debate between Trump and Biden

View Video

View Video

October 20th, 2020, 08:13 PM EDT

WTOP Huddle: Should Allen remain starting QB? A look ahead to Sunday’s game against Dallas

View Video

View Video

October 16th, 2020, 11:31 PM EDT

Sshh! He can hear you: National Zoo’s baby giant panda turns 8 weeks old

View Video

View Video

October 14th, 2020, 08:31 AM EDT

WATCH: Day 3 of hearings for Supreme Court nominee Barrett

View Video

View Video

October 13th, 2020, 09:11 PM EDT

WTOP Huddle: Is the Washington Football Team trying to win now?

View Video

View Video

October 12th, 2020, 07:27 AM EDT

WATCH: Confirmation hearings for Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett

View Video

View Video

October 7th, 2020, 10:19 PM EDT

WTOP Huddle: Washington benches QB Haskins, switches to Allen vs. Rams

View Video

View Video

September 29th, 2020, 11:13 PM EDT

WTOP Huddle: What happened to Burgundy and Gold in week 3 and what about playing the Ravens this weekend?

View Video

View Video

September 25th, 2020, 03:36 PM EDT

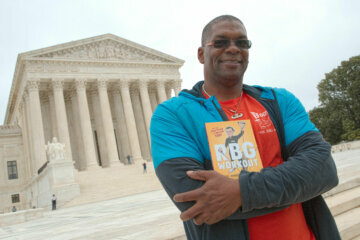

Ginsburg’s longtime personal trainer honors the late justice with pushups

View Video

View Video

September 24th, 2020, 08:59 AM EDT

Meghan makes surprise ‘America’s Got Talent’ appearance

View Video

View Video

September 24th, 2020, 08:12 AM EDT

WATCH: Ruth Bader Ginsburg lies in repose at Supreme Court

View Video

View Video

September 24th, 2020, 02:09 AM EDT

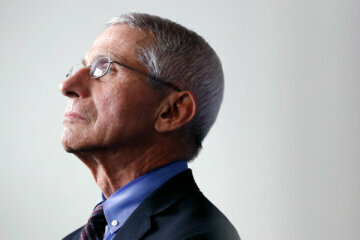

Fauci cautions that a COVID-19 vaccine won’t eliminate the need for masks and public health measures

View Video

View Video

September 23rd, 2020, 12:16 PM EDT

WTOP Huddle: What happened to Burgundy and Gold in week 2?

View Video

View Video

September 17th, 2020, 02:14 PM EDT

WTOP Huddle: WTOP Sports team looks back at NFL’s first week

View Video

View Video

August 25th, 2020, 11:12 AM EDT

Inside China’s new lab conducting late-stage vaccine trials

View Video

View Video

August 21st, 2020, 08:19 AM EDT

WATCH: Postmaster General Louis DeJoy testifies before Senate

View Video

View Video

August 14th, 2020, 11:22 AM EDT

RZA came up with a new ice cream truck jingle because the old one was used in minstrel shows

View Video

View Video

August 14th, 2020, 05:38 AM EDT

How 11-year-old Gui Khury made skateboarding history with first 1080 on a vertical ramp

View Video

View Video

August 12th, 2020, 01:40 PM EDT

WATCH: Joe Biden introduces Kamala Harris as running mate

View Video

View Video

July 31st, 2020, 03:10 PM EDT

Nike’s viral ‘You Can’t Stop Us’ ad is winning big on social media

View Video

View Video

July 31st, 2020, 02:01 PM EDT

Human sperm roll like ‘playful otters’ as they swim, study finds, contradicting centuries-old beliefs

View Video

View Video

July 31st, 2020, 01:00 PM EDT

Health officials testify before House panel on national pandemic plan

View Video

View Video

July 28th, 2020, 03:57 PM EDT

WATCH: Civil rights icon John Lewis lies in state on Capitol steps

View Video

View Video

July 27th, 2020, 10:30 PM EDT

WATCH: Civil rights icon John Lewis lies in state at US Capitol

View Video

View Video

July 26th, 2020, 10:50 AM EDT

WATCH LIVE: John Lewis crosses Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge for final time

View Video

View Video

July 25th, 2020, 06:45 PM EDT

Watch: Selma honors congressman, civil rights icon John Lewis

View Video

View Video

July 20th, 2020, 11:21 AM EDT

Gap shares fall after Kanye West threatens to walk away from Yeezy deal

View Video

View Video

July 20th, 2020, 08:44 AM EDT

Police in Italy find shipment of coffee beans stuffed with cocaine

View Video

View Video

July 19th, 2020, 08:47 PM EDT

Online petition calls on Trader Joe’s to change its ‘racist packaging’

View Video

View Video

June 26th, 2020, 09:34 AM EDT

MGM National Harbor shows off changes ahead of Monday reopening

View Video

View Video

June 11th, 2020, 04:08 AM EDT

How the ‘Juventus Way’ helped young Montgomery Co. soccer players during pandemic

View Video

View Video

June 10th, 2020, 02:57 PM EDT

Medical supply company threw out products after Trump toured its facility

View Video

View Video

June 10th, 2020, 01:34 PM EDT

Here’s what’s getting more expensive — and cheaper — at the grocery store

View Video

View Video

June 9th, 2020, 12:56 AM EDT

NASCAR’s Bubba Wallace will have Black Lives Matter paint scheme on car at Martinsville Speedway race

View Video

View Video

June 6th, 2020, 02:04 PM EDT

WATCH: Thousands gather on sweltering day in DC for 9th day of protests

View Video

View Video

June 2nd, 2020, 11:22 AM EDT

WATCH: Trump to visit DC’s Saint John Paul II National Shrine

View Video

View Video

May 29th, 2020, 11:01 AM EDT

LIVE VIDEO: Minnesota governor holds briefing following Minneapolis protests

View Video

View Video

May 20th, 2020, 01:51 PM EDT

VIDEO: WTOP anchor finds 100+ used gloves, masks littered around Northwest DC

View Video

View Video

May 19th, 2020, 01:15 PM EDT

Mnuchin, Powell testify to Senate panel about small-business lending effort

View Video

View Video

May 12th, 2020, 07:32 AM EDT

WATCH: Dr. Fauci, health officials testify before Senate committee on reopening US

View Video

View Video

May 5th, 2020, 02:24 PM EDT

A Dollar Tree worker told a man he needed a mask, so he wiped his face on her shirt, police say

View Video

View Video

May 5th, 2020, 01:22 AM EDT

A 5-year-old boy was pulled over in Utah on his way to California to try to buy a Lamborghini

View Video

View Video

May 4th, 2020, 10:14 PM EDT

Park ranger was telling a crowd to social distance. Mid-speech, someone pushed him into a lake

View Video

View Video

May 1st, 2020, 02:09 PM EDT

Maryland sixth grader who helped create 1,000 masks gets Caps surprise

View Video

View Video

April 29th, 2020, 09:52 AM EDT

Stephen Colbert and Jake Gyllenhaal bonded over sourdough starter

View Video

View Video

April 28th, 2020, 10:34 PM EDT

Quarterback Alex Smith’s grueling road to recovery chronicled in ESPN program

View Video

View Video

April 28th, 2020, 11:56 AM EDT

A reporter went on air wearing a suit coat and no pants, not realizing everyone could see his legs

View Video

View Video

April 27th, 2020, 06:01 AM EDT

MASN Sports’ Melewski on the passing of legendary pitcher Steve Dalkowski

View Video

View Video

April 15th, 2020, 03:49 PM EDT

With no tourists around, animals at Yosemite are ‘having a party’

View Video

View Video

April 15th, 2020, 03:48 PM EDT

When the ventilator comes off, the delirium comes out for many coronavirus survivors

View Video

View Video

April 14th, 2020, 01:07 PM EDT

Respiratory therapist with coronavirus gives birth to a daughter while in a medically induced coma

View Video

View Video

April 14th, 2020, 10:13 AM EDT

Swizz Beatz and Timbaland want to keep us entertained and in the light amid coronavirus

View Video

View Video

April 13th, 2020, 05:49 PM EDT

Brad Pitt’s HGTV debut on ‘Celebrity IOU’ is the feel-good TV we all need

View Video

View Video

April 12th, 2020, 10:32 AM EDT

WATCH LIVE: National Cathedral holds virtual Easter Sunday services

View Video

View Video

April 10th, 2020, 05:13 AM EDT

Climbing the height of Mount Everest from the comfort of your own home

View Video

View Video

April 9th, 2020, 09:36 AM EDT

Joseph Gordon-Levitt wants to hear your coronavirus stories

View Video

View Video

April 3rd, 2020, 03:26 PM EDT

People living in vans and RVs are getting squeezed during pandemic

View Video

View Video

March 30th, 2020, 09:58 AM EDT

John Krasinski and Steve Carell gave us a mini ‘The Office’ reunion

View Video

View Video

March 24th, 2020, 01:54 AM EDT

What these 34-year-old and 26-year-old coronavirus patients have to say to young adults

View Video

View Video

March 23rd, 2020, 09:31 PM EDT

Care home nurse tells of terrifying and sudden ways coronavirus struck her patients

View Video

View Video

March 23rd, 2020, 07:38 PM EDT

A man ran the length of a marathon all from his balcony during France’s coronavirus lockdown

View Video

View Video

March 20th, 2020, 10:47 AM EDT

WATCH: White House daily coronavirus briefing for March 20

View Video

View Video

March 19th, 2020, 10:27 AM EDT

WATCH: White House daily coronavirus briefing for March 19

View Video

View Video

March 18th, 2020, 10:51 AM EDT

WATCH: White House daily coronavirus briefing for March 18

View Video

View Video

March 17th, 2020, 12:45 PM EDT

Two siblings held a porch concert for a neighbor who is self-isolating

View Video

View Video

March 17th, 2020, 10:39 AM EDT

WATCH LIVE: White House coronavirus task force gives update March 17

View Video

View Video

March 17th, 2020, 12:43 AM EDT

This student created a network of ‘shopping angels’ to help the elderly get groceries during the coronavirus pandemic

View Video

View Video

March 11th, 2020, 07:23 PM EDT

WATCH: Trump suspends travel between US and Europe for 30 days

View Video

View Video

March 9th, 2020, 09:56 AM EDT

Highest sky deck in Western Hemisphere dares visitors to live on the edge

View Video

View Video

March 9th, 2020, 08:35 AM EDT

For her 75th birthday, Dolly Parton wants to be on the cover of Playboy

View Video

View Video

March 8th, 2020, 04:02 AM EDT

Lieutenant Dan the two-legged hound is competing to be the next Cadbury Bunny

View Video

View Video

February 28th, 2020, 10:32 AM EST

VIDEO: Cops confiscate Batmobile replica during traffic stop

View Video

View Video

February 26th, 2020, 05:21 PM EST

WATCH: Trump says US ‘very ready’ for virus; Pence to lead response

View Video

View Video

February 25th, 2020, 06:24 PM EST

WATCH: USPS worker’s reunion with Howard County boy he found along I-95

View Video

View Video

February 21st, 2020, 07:45 AM EST

WATCH: Nats celebrate World Series with parade ahead of Spring Training opener in Florida

View Video

View Video

February 20th, 2020, 08:17 AM EST

Contigo recalls nearly 6 million of its kids water bottles due to a choking hazard. Again.

View Video

View Video

February 20th, 2020, 06:51 AM EST

Julie Walters reveals she was diagnosed with bowel cancer

View Video

View Video

February 19th, 2020, 09:03 PM EST

WATCH: Bloomberg, Sanders under attack at Democrats’ Nevada debate

View Video

View Video

February 19th, 2020, 10:02 AM EST

Lark Voorhies ‘a bit slighted and hurt’ by ‘Saved by the Bell’ reunion snub

View Video

View Video

February 14th, 2020, 03:30 PM EST

Prince William County man scratches $10M winning lottery ticket

View Video

View Video

February 13th, 2020, 07:20 AM EST

A 2-year-old boy’s reaction to a Target ad is powerful reminder of why representation matters

View Video

View Video

February 13th, 2020, 07:18 AM EST

A 6-year-old girl found a note at the grocery store with a surprise tucked inside

View Video

View Video

February 12th, 2020, 11:22 AM EST

Worker on board Diamond Princess says crew are at greater risk of coronavirus

View Video

View Video

February 12th, 2020, 10:35 AM EST

WATCH: LA Zoo welcomes first baby gorilla in over 20 years

View Video

View Video

February 12th, 2020, 07:17 AM EST

He was 6 inches from being hit with a steel beam. A steering wheel saved him

View Video

View Video

February 11th, 2020, 02:56 PM EST

Mysterious radio signal from space is repeating every 16 days

View Video

View Video

February 11th, 2020, 11:53 AM EST

Dwyane Wade is proud to support his 12-year-old to live in her truth

View Video

View Video

February 7th, 2020, 06:06 PM EST

VIDEO: All that political tension in DC? ‘Everyone’s hangry,’ AOC says

View Video

View Video

February 5th, 2020, 11:05 AM EST

Watch: Camera captures dog starting fire in New Mexico house

View Video

View Video

February 3rd, 2020, 05:00 PM EST

WATCH: Impeachment trial resumes with Senate poised to acquit

View Video

View Video

February 2nd, 2020, 07:30 AM EST

WATCH: Punxsutawney Phil makes his forecast on Groundhog Day 2020

View Video

View Video

January 29th, 2020, 12:19 PM EST

‘Mighty Ducks’ actor Shaun Weiss accused of breaking into man’s garage while high on meth

View Video

View Video

January 29th, 2020, 07:41 AM EST

A 9-year-old boy who can deadlift more than twice his bodyweight is breaking powerlifting records

View Video

View Video

January 26th, 2020, 05:35 PM EST

WATCH LIVE: LA County Sheriff’s Dept. briefing on Kobe Bryant helicopter crash

View Video

View Video

January 25th, 2020, 09:36 AM EST

WATCH LIVE: Trump’s defense team makes case in impeachment trial

View Video

View Video

January 19th, 2020, 03:18 PM EST

An abandoned husky with ‘weird’ eyes has been adopted after her photos went viral

View Video

View Video

January 17th, 2020, 01:26 PM EST

Without warning, Eminem drops new album ‘Music to be Murdered by’

View Video

View Video

January 16th, 2020, 12:25 PM EST

WATCH: Senators sworn in ahead of impeachment proceedings

View Video

View Video

January 15th, 2020, 09:50 AM EST

WATCH: Pelosi names Schiff, Nadler as prosecutors for Trump trial

View Video

View Video

January 10th, 2020, 10:09 AM EST

WATCH: ‘Jeopardy!’ greats go head to head in game show showdown

View Video

View Video

January 9th, 2020, 10:57 AM EST

WATCH: Burglar cooks food and takes nap in Georgia Taco Bell

View Video

View Video

January 7th, 2020, 02:23 PM EST

Why Netflix is partnering with Goop and its controversies

View Video

View Video

January 7th, 2020, 11:57 AM EST

Punta Ventana, one of Puerto Rico’s natural wonders, has been destroyed by an earthquake

View Video

View Video

January 7th, 2020, 09:43 AM EST

Michelle Obama to highlight college students’ first year in new Instagram TV series

View Video

View Video

January 7th, 2020, 01:37 AM EST

NASA astronaut shares beautiful image of 2020’s first meteor shower

View Video

View Video

January 2nd, 2020, 02:49 PM EST

A family thought they were just baking a pizza. Then they found a snake inside their oven

View Video

View Video

January 2nd, 2020, 11:39 AM EST

Ricki Lake reveals she’s been struggling with the ‘quiet hell’ of hair loss for 30 years

View Video

View Video

January 1st, 2020, 04:40 PM EST

Bells ring at Washington National Cathedral in harmonious start of the new year

View Video

View Video

January 1st, 2020, 06:41 AM EST

From plastic bags to natural hair, here are the new laws coming in 2020

View Video

View Video

December 31st, 2019, 10:46 AM EST

Two puffins scratched their itches with sticks — the first evidence that seabirds can use tools

View Video

View Video

December 31st, 2019, 10:15 AM EST

Michelle Williams and ‘Hamilton’ director Thomas Kail are engaged and expecting

View Video

View Video

December 30th, 2019, 03:39 PM EST

A 12-year-old got a magnifying glass for Christmas — and set his lawn on fire

View Video

View Video

December 30th, 2019, 12:11 PM EST

Trump and Obama tied for the most admired men in the US this year. Michelle is the most admired woman, Gallup reports

View Video

View Video

December 24th, 2019, 10:32 AM EST

VIDEO: Washington Capitals show their Christmas spirit with Captain

View Video

View Video

December 13th, 2019, 08:26 AM EST

WATCH: House Judiciary votes on articles of impeachment

View Video

View Video

December 12th, 2019, 07:56 AM EST

WATCH AND LISTEN LIVE: House Judiciary draws up formal articles of impeachment

View Video

View Video

December 11th, 2019, 05:35 PM EST

Michelle Obama helps give out iPads, $100K to Southeast DC school

View Video

View Video

December 10th, 2019, 08:28 AM EST

WATCH: Democrats unveil impeachment articles against Trump

View Video

View Video

December 5th, 2019, 08:33 AM EST

WATCH: Speaker Nancy Pelosi says House will draft articles of impeachment

View Video

View Video

December 4th, 2019, 07:51 AM EST

WATCH: House Judiciary Committee’s 1st Trump impeachment hearing

View Video

View Video

December 4th, 2019, 03:18 AM EST

A polar bear was spray-painted with graffiti. Experts fear it won’t survive

View Video

View Video

December 2nd, 2019, 10:21 AM EST

Robert De Niro defends Anna Paquin’s role in ‘The Irishman’

View Video

View Video

November 25th, 2019, 08:00 PM EST

No easy mark: Female bodybuilder, 82, clobbers intruder

View Video

View Video

November 22nd, 2019, 03:15 PM EST

WATCH: A Boeing 777 lands safely back in Los Angeles after flames shoot from an engine

View Video

View Video

November 22nd, 2019, 02:57 PM EST

WATCH: Remember when Fred Rogers swapped his sport coat for a knit cardigan?

View Video

View Video

November 21st, 2019, 01:02 AM EST

Koala rescued from Australia bushfire is reunited with hero grandma

View Video

View Video

November 20th, 2019, 08:15 PM EST

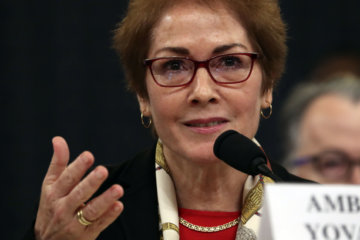

WATCH: Impeachment panel grills US ambassador to EU and Defense, State officials

View Video

View Video

November 20th, 2019, 12:54 PM EST

More than 140 ancient geoglyphs were found carved in the sands of Peru

View Video

View Video

November 19th, 2019, 08:17 PM EST

WATCH AND LISTEN: Day 3 of impeachment hearings wraps up after long day of testimonies

View Video

View Video

November 19th, 2019, 10:11 AM EST

The ‘Dancing With the Stars’ semifinals left the audience and contestants in tears

View Video

View Video

November 19th, 2019, 12:08 AM EST

A new Uno deck promises to keep families away from politics at Thanksgiving dinner

View Video

View Video

November 18th, 2019, 02:17 PM EST

‘Jeopardy! The Greatest of All Time’ premiering in January

View Video

View Video

November 17th, 2019, 06:55 PM EST

Taco Bell wants you to take its tacos, stick ’em in a blender, and serve them as bisque this Thanksgiving

View Video

View Video

November 16th, 2019, 08:25 PM EST

Florida couple gives birth to boy thanks to ‘Win a Baby’ contest

View Video

View Video

November 16th, 2019, 03:54 PM EST

Kanye West performed a surprise concert for inmates at Houston jail

View Video

View Video

November 15th, 2019, 03:45 PM EST

VIDEO: House impeachment inquiry of President Trump continues

View Video

View Video

November 13th, 2019, 12:17 PM EST

Minecraft Earth is available in the US for fans hoping to play the AR game early

View Video

View Video

November 12th, 2019, 11:41 AM EST

We bought a $1 house in Italy. Here’s what happened next

View Video

View Video

November 11th, 2019, 09:48 PM EST

Alex Trebek chokes up on ‘Jeopardy!’ after contestant’s heartfelt message

View Video

View Video

November 11th, 2019, 04:03 PM EST

A World War II submarine that was missing for 75 years has been found off Okinawa, Japan

View Video

View Video

November 11th, 2019, 01:14 PM EST

A judge held a law student’s baby so that the boy could be part of his mother’s swearing-in ceremony

View Video

View Video

November 11th, 2019, 12:21 PM EST

Tiny deer-like animal thought lost to science photographed for first time in 30 years

View Video

View Video

November 7th, 2019, 12:42 PM EST

The woman accused of entering the Bronx Zoo lion enclosure was arrested

View Video

View Video

November 6th, 2019, 01:11 PM EST

A 25-year-old politician got heckled during a climate crisis speech. Her deadpan retort: ‘OK, boomer’

View Video

View Video

November 6th, 2019, 08:01 AM EST

‘It didn’t have to end with a bowl’: Democrat beats GOP incumbent to win seat she lost in 2017 after tie-breaking pick

View Video

View Video

November 6th, 2019, 04:30 AM EST

Our poor, unfortunate souls are grateful for Queen Latifah’s Ursula in ‘The Little Mermaid Live’

View Video

View Video

November 5th, 2019, 11:56 PM EST

Cyclist who flipped off Trump motorcade wins local office in Virginia

View Video

View Video

November 5th, 2019, 03:50 PM EST

Jimmy Kimmel shares parents’ pranks on kids’ Halloween joy

View Video

View Video

November 4th, 2019, 10:08 PM EST

Krispy Kreme reverses course, allows student resale service

View Video

View Video

October 31st, 2019, 09:20 PM EDT

WATCH: World Series champs Nats get hero’s welcome at Dulles International Airport

View Video

View Video

October 29th, 2019, 02:23 PM EDT

Holy guacamole! Thousands of avocados spilled on Texas highway

View Video

View Video

October 29th, 2019, 01:26 PM EDT

Halloween costumes wouldn’t fit his son’s wheelchair. Now he builds epic outfits himself

View Video

View Video

October 29th, 2019, 09:13 AM EDT

Retired doctor, 67, gives birth in China after getting ‘pregnant naturally’

View Video

View Video

October 28th, 2019, 12:46 PM EDT

Authorities identify victim of gender reveal party explosion

View Video

View Video

October 28th, 2019, 07:30 AM EDT

Popeyes’ spicy chicken sandwich is officially coming back

View Video

View Video

October 27th, 2019, 01:30 PM EDT

Man wins $200,000 lottery prize on the way to his last chemo treatment

View Video

View Video

October 26th, 2019, 01:22 PM EDT

A fat cat named Cinderblock wins over the internet with its heartwarming workout routine

View Video

View Video

October 24th, 2019, 09:14 AM EDT

WATCH: Rep. Elijah Cummings lies in state at Capitol ceremony

View Video

View Video

October 23rd, 2019, 09:57 AM EDT

Kelly Clarkson’s new talk show is a hit. Here’s why that’s a big deal

View Video

View Video

October 22nd, 2019, 09:31 AM EDT

Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash’s demo of ‘Wanted Man’ is released

View Video

View Video

October 21st, 2019, 05:54 PM EDT

Researchers discover Japanese carrier from the World War II Battle of Midway

View Video

View Video

October 21st, 2019, 06:40 AM EDT

A girls soccer team was penalized for their ‘equal pay’ shirts. Now their message is being celebrated

View Video

View Video

October 18th, 2019, 11:37 AM EDT

WATCH: Woman falls onto subway tracks and is pulled to safety

View Video

View Video

October 15th, 2019, 12:00 PM EDT

Here are all the movies and TV shows you can binge on when Disney+ launches

View Video

View Video

October 15th, 2019, 08:15 AM EDT

Fortnite is back online with a new chapter after two-day hiatus

View Video

View Video

October 14th, 2019, 09:15 PM EDT

A massive mastiff had to be rescued after getting exhausted on a mountain hike

View Video

View Video

October 14th, 2019, 03:01 PM EDT

Panera defends its mac and cheese after a video exposed the menu item is, gasp, cooked in a bag

View Video

View Video

October 14th, 2019, 12:16 PM EDT

Search resumes for worker missing in fatal New Orleans building collapse

View Video

View Video

October 10th, 2019, 08:26 AM EDT

Ed Sheeran and Prince Harry unite in video for World Mental Health Day

View Video

View Video

October 9th, 2019, 09:57 PM EDT

‘Riverdale’ bid farewell to Luke Perry in emotional episode

View Video

View Video

October 9th, 2019, 11:28 AM EDT

Swiss climbs 1,800-foot vertical rock face in record time … without a safety rope

View Video

View Video

October 9th, 2019, 09:52 AM EDT

Virgin Atlantic’s seat messaging system has been flagged by travelers for years

View Video

View Video

October 8th, 2019, 06:38 PM EDT

What happened to this car is nuts. 200 walnuts, to be exact

View Video

View Video

October 8th, 2019, 11:07 AM EDT

Eagles plan massive ‘Hotel California’ performances on tour

View Video

View Video

October 8th, 2019, 06:35 AM EDT

Ellen DeGeneres explains hanging out with her friend George W. Bush

View Video

View Video

October 7th, 2019, 02:38 PM EDT

This record-breaking pumpkin is heavier than a small car and big enough to fit inside

View Video

View Video

October 7th, 2019, 10:20 AM EDT

Alex Trebek says his pancreatic cancer may mean the end of his time at ‘Jeopardy!’

View Video

View Video

October 6th, 2019, 03:44 PM EDT

Paul McCartney and Mick Jagger among musicians paying tribute to Cream drummer Ginger Baker

View Video

View Video

October 4th, 2019, 11:18 AM EDT

Post-surgery Taylor Swift nearly has meltdown over a banana

View Video

View Video

October 4th, 2019, 11:13 AM EDT

WATCH: Here’s what it’s like to fly in an Uber helicopter

View Video

View Video

October 3rd, 2019, 06:00 PM EDT

WATCH: Washington National Cathedral’s choristers give Nats a sweet serenade

View Video

View Video

October 3rd, 2019, 10:50 AM EDT

A Texas cheerleader jumped off a homecoming float to save a choking boy

View Video

View Video

October 3rd, 2019, 08:13 AM EDT

Is this hydrogen-powered vessel the superyacht of the future?

View Video

View Video

October 2nd, 2019, 06:47 PM EDT

Mounted officer said ‘this is gonna look really bad’ before leading an arrested man down the street in Galveston

View Video

View Video

October 2nd, 2019, 03:32 AM EDT

Indonesia cancels plan to ban tourists from Komodo Island

View Video

View Video

October 1st, 2019, 05:14 PM EDT

The Bronx Zoo says a woman seen dancing inside its lion enclosure could have been seriously hurt or killed

View Video

View Video

October 1st, 2019, 10:55 AM EDT

Taiwan bridge collapses, sending truck plunging onto fishing boats

View Video

View Video

October 1st, 2019, 02:58 AM EDT

Catering cart causes chaos at Chicago airport, but American Airlines employee saves the day

View Video

View Video

September 30th, 2019, 09:52 AM EDT

‘They need the cool factor’: Tony Hawk on skateboarding at Tokyo 2020

View Video

View Video

September 29th, 2019, 07:23 PM EDT

Florida family mourns the loss of hero pit bull, who died protecting their children from a venomous snake

View Video

View Video

September 27th, 2019, 11:44 AM EDT

The world’s first transgender professional boxer is now the face of Everlast

View Video

View Video

September 27th, 2019, 09:50 AM EDT

Prince Harry walks through Angola mine field, echoing Diana

View Video

View Video

September 26th, 2019, 09:34 AM EDT

WATCH: Acting DNI Director Joseph Maguire testifies before Congress on whistleblower complaint

View Video

View Video

September 26th, 2019, 05:21 AM EDT

Airline introduces baby seat map to allow passengers to avoid infants

View Video

View Video

September 25th, 2019, 09:15 AM EDT

These sea otters adopt orphaned pups and raise them to be wild

View Video

View Video

September 25th, 2019, 06:59 AM EDT

The world’s largest offshore wind farm is nearly complete. It can power 1 million homes

View Video

View Video

September 25th, 2019, 06:19 AM EDT

Beijing’s Daxing International Airport now officially open

View Video

View Video

September 24th, 2019, 11:22 AM EDT

A herd of spotted cows made a late-night visit to Spotted Cow brewery

View Video

View Video

September 24th, 2019, 09:36 AM EDT

Will Smith and Jada Pinkett Smith staged an intervention with son Jaden

View Video

View Video

September 23rd, 2019, 11:34 AM EDT

Greta Thunberg and 15 other children filed a complaint against five countries over the climate crisis

View Video

View Video

September 23rd, 2019, 10:07 AM EDT

‘Oprah’s Book Club’ series is set to premiere on Apple TV+

View Video

View Video

September 20th, 2019, 11:24 AM EDT

Are the iPhone 11 and iPhone 11 Pro worth the upgrade?

View Video

View Video

September 19th, 2019, 11:21 AM EDT

A university studied the water quality on planes. You may want to skip the coffee on these two airlines

View Video

View Video

September 18th, 2019, 11:09 AM EDT

VA puts regional director on leave after veteran found covered in ants at assisted-living facility

View Video

View Video

September 18th, 2019, 10:44 AM EDT

Sandy Hook Promise’s chilling back-to-school PSA hopes to prevent mass shootings

View Video

View Video

September 18th, 2019, 09:32 AM EDT

‘The Princess Bride’ remake idea has people crying inconceivable

View Video

View Video

September 17th, 2019, 09:06 PM EDT

A fan held a sign on ‘College GameDay’ asking people to Venmo him money for beer. Now he’s donating it all to a children’s hospital

View Video

View Video

September 17th, 2019, 10:43 AM EDT

Cancer survivor becomes first person to swim English Channel four times non-stop

View Video

View Video

September 17th, 2019, 09:48 AM EDT

‘Jeopardy!’ host Trebek says he’s resumed chemotherapy

View Video

View Video

September 16th, 2019, 11:44 AM EDT

Christie Brinkley drops out of ‘Dancing with the Stars’ due to injury, so her daughter is stepping in

View Video

View Video

September 13th, 2019, 03:03 PM EDT

This photographer captures airplanes’ technicolor rainbow trails

View Video

View Video

September 13th, 2019, 11:34 AM EDT

A baby born at 9:11 p.m. on 9/11 weighed 9 pounds, 11 ounces

View Video

View Video

September 13th, 2019, 09:43 AM EDT

‘I always look orange’: Trump rails against energy-efficient light bulbs and Democratic environmental policies

View Video

View Video

September 11th, 2019, 11:21 PM EDT

Report: Justify failed drug test before Triple Crown run

View Video

View Video

September 11th, 2019, 07:13 PM EDT

WATCH: ‘Tribute in Light’ shines for 9/11 victims in New York City

View Video

View Video

September 11th, 2019, 02:41 PM EDT

He spent his entire life pranking others. Now his family is sending him off with a comedic obituary

View Video

View Video

September 11th, 2019, 10:59 AM EDT

VIDEO: Erectile dysfunction may predict strokes and heart attacks

View Video

View Video

September 10th, 2019, 04:59 PM EDT

Asteroid as powerful as 10 billion WWII atomic bombs may have wiped out the dinosaurs

View Video

View Video

September 10th, 2019, 03:55 PM EDT

WATCH: Visitors can soon see rare clouded leopard cubs at National Zoo

View Video

View Video

September 10th, 2019, 03:24 PM EDT

These two toddlers are showing us what real-life besties look like

View Video

View Video

September 9th, 2019, 05:29 PM EDT

Virtual reality is part of new tech used in GW’s operating rooms

View Video

View Video

September 9th, 2019, 10:00 AM EDT

Trump slams John Legend for not helping with justice reform

View Video

View Video

September 8th, 2019, 06:11 PM EDT

NASA remixed an Ariana Grande song to promote its mission to put a woman on the moon

View Video

View Video

September 8th, 2019, 03:05 PM EDT

Robert Axelrod, the voice of Lord Zedd in ‘Mighty Morphin Power Rangers,’ dies at 70

View Video

View Video

September 6th, 2019, 11:18 AM EDT

Owner of the Jeep abandoned in the surf on Myrtle Beach during Hurricane Dorian explains how it got there

View Video

View Video

September 6th, 2019, 09:52 AM EDT

A man watched on doorbell camera as a tornado from Hurricane Dorian destroyed his home

View Video

View Video

September 5th, 2019, 11:07 AM EDT

Friends with benefits: Can Facebook tackle your love life?

View Video

View Video

September 4th, 2019, 12:35 PM EDT

Porsche’s first electric car can go from 0 to 60 mph in under 3 seconds

View Video

View Video

September 4th, 2019, 02:44 AM EDT

US woman held in Philippines after airport staff find baby in her bag

View Video

View Video

September 3rd, 2019, 09:14 PM EDT

World’s most livable city for 2019, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit

View Video

View Video

September 3rd, 2019, 01:43 PM EDT

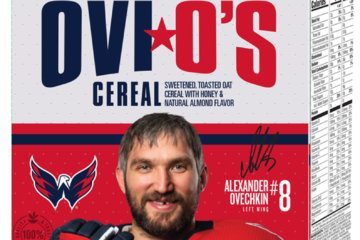

VIDEO: Ovechkin celebrates Ovi O’s impending launch, tosses himself some cereal

View Video

View Video

September 2nd, 2019, 09:53 AM EDT

Electric vehicles will change how all cars look forever

View Video

View Video

August 28th, 2019, 11:34 AM EDT

Trump thinks Fox News isn’t doing enough to promote his presidency

View Video

View Video

August 27th, 2019, 03:24 PM EDT

Basketball-sized world-record grapefruit grown in Louisiana

View Video

View Video

August 22nd, 2019, 01:19 PM EDT

Little League World Series essentials: Bats, balls … cardboard?!

View Video

View Video

August 21st, 2019, 09:01 AM EDT

USWNT star Carli Lloyd drills a 55-yard field goal at a Philadelphia Eagles practice

View Video

View Video

August 20th, 2019, 08:00 AM EDT

Samuel L. Jackson’s lightsaber and Jack Nicholson’s ‘The Shining’ axe on offer at movie prop auction

View Video

View Video

August 19th, 2019, 07:32 AM EDT

A daredevil broke a 24-year cycling speed record, hitting 174 miles per hour

View Video

View Video

August 14th, 2019, 10:38 AM EDT

Jury awards man $50 Million after he says officers beat him, locked him in closet

View Video

View Video

August 14th, 2019, 09:10 AM EDT

A 12-year-old snags a mammoth discovery while on vacation in Ohio

View Video

View Video

August 13th, 2019, 10:36 PM EDT

Jay-Z’s Roc Nation and NFL join forces for music and social justice

View Video

View Video

August 13th, 2019, 11:31 AM EDT

The guy behind the ‘Storm Area 51’ Facebook event is hosting an alien-themed festival

View Video

View Video

August 12th, 2019, 06:33 PM EDT

Missing dentures found stuck in throat 8 days after surgery

View Video

View Video

August 12th, 2019, 11:16 AM EDT

NC woman took her 3 dogs to a pond to play. Within hours, dogs died from toxic algae

View Video

View Video

August 12th, 2019, 07:41 AM EDT

Scaramucci no longer backs Trump’s reelection, says change may be needed at top of ticket

View Video

View Video

August 9th, 2019, 10:21 AM EDT

Illinois man ‘adopts’ forgotten road barricade, celebrates birthdays and holidays with it

View Video

View Video

August 7th, 2019, 11:18 AM EDT

Oscar-winning Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro champions immigrants in Hollywood Walk of Fame speech

View Video

View Video

August 7th, 2019, 09:53 AM EDT

Ariana Grande left sobbing over her live duet with Barbra Streisand

View Video

View Video

August 7th, 2019, 09:04 AM EDT

World’s first launched water coaster, Cheetah Chase, coming in 2020

View Video

View Video

August 7th, 2019, 07:22 AM EDT

Northern Virginia quartet Voices of Service advances in ‘America’s Got Talent’

View Video

View Video

August 6th, 2019, 03:59 PM EDT

Tom Brady and Gisele Bündchen’s Boston-area mansion was just listed for a cool $39,500,000

View Video

View Video

August 6th, 2019, 03:06 PM EDT

A woman shared a cruel note that was left in her mailbox. She never imagined the kindness that would come next

View Video

View Video

August 5th, 2019, 12:41 PM EDT

Robert De Niro and chef Nobu Matsuhisa share their hospitality secrets

View Video

View Video

August 5th, 2019, 04:27 AM EDT

Shooting victims include a mom who died protecting her baby

View Video

View Video

August 5th, 2019, 03:45 AM EDT

Neil deGrasse Tyson is facing backlash after tweeting about shooting deaths

View Video

View Video

August 2nd, 2019, 11:19 AM EDT

A gun store’s billboard targeting the freshmen congresswomen known as the ‘Squad’ is coming down

View Video

View Video

August 2nd, 2019, 11:10 AM EDT

Pilot makes emergency landing on highway — all captured on trooper’s dashcam

View Video

View Video

July 31st, 2019, 09:39 AM EDT

See a crowd catch a boy who fell from a sixth-floor balcony

View Video

View Video

July 31st, 2019, 04:52 AM EDT

Mystery as surgical plate found in 15-foot crocodile’s stomach

View Video

View Video

July 31st, 2019, 04:39 AM EDT

A glass bridge opening next month in China will be the world’s longest

View Video

View Video

July 30th, 2019, 02:53 PM EDT

Trump on Baltimore: ‘They really appreciate what I’m doing’

View Video

View Video

July 30th, 2019, 01:33 PM EDT

Your heartburn drugs may be giving you allergies, study suggests

View Video

View Video

July 30th, 2019, 11:01 AM EDT

WATCH: Trump speaks at celebration of American democracy’s 400th birthday in Jamestown

View Video

View Video

July 28th, 2019, 04:18 AM EDT

Stop sweating the great white shark. Here’s the one you should really be worried about

View Video

View Video

July 26th, 2019, 09:41 AM EDT

Kar-go is Europe’s first road-worthy autonomous delivery vehicle

View Video

View Video

July 25th, 2019, 07:51 AM EDT

See hoverboard daredevil attempt to cross the English Channel

View Video

View Video

July 24th, 2019, 01:40 PM EDT

Police search for owners of flag found on Prince George’s Co. road

View Video

View Video

July 23rd, 2019, 08:04 AM EDT

WATCH: FBI Director Christopher Wray testifies before Senate committee

View Video

View Video

July 22nd, 2019, 10:15 AM EDT

Tom Hanks is absolutely perfect as Mister Rogers in new movie trailer

View Video

View Video

July 19th, 2019, 07:20 PM EDT

Tom Cruise surprises Comic-Con with ‘Top Gun’ sequel trailer

View Video

View Video

July 19th, 2019, 12:05 PM EDT

No one wants the middle seat on airplanes. This design could change that

View Video

View Video

July 19th, 2019, 04:40 AM EDT

Tiger takes catnap on bed in Indian home after fleeing huge floods

View Video

View Video

July 18th, 2019, 08:26 AM EDT

Kids with disabilities can now get special Halloween costumes at Target

View Video

View Video

July 17th, 2019, 04:12 PM EDT

John Lewis on Trump in emotional speech: ‘I know racism when I feel it’