This story is part of the WTOP series, “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.” Each day this week, we’ll tell the stories of the upheaval and tumult 50 years ago through the eyes of those who experienced it.

WASHINGTON — It was Steve Souder’s first day on the job as a dispatcher for the D.C. Fire Department.

The 28-year-old had been on the force for seven years at that point but had been placed on desk duty because of a bum knee. When he arrived at the department’s communications center that early spring Thursday afternoon, the radio dispatcher already on the clock was itching to leave.

“And he said, ‘Have you ever done this before?’ And I said, ‘No sir,’” Souder recalled. “And he said, ‘Well, all you do is push the button when you want to talk, and leave off the button when you don’t want to talk.’ … So he said: ‘You been trained. I’ll see you later.’ And he got up, and I sat down — and that was my first day on the job as a dispatcher.”

The new guy was suddenly responsible for running the entire department’s switchboard.

It was April 4, 1968.

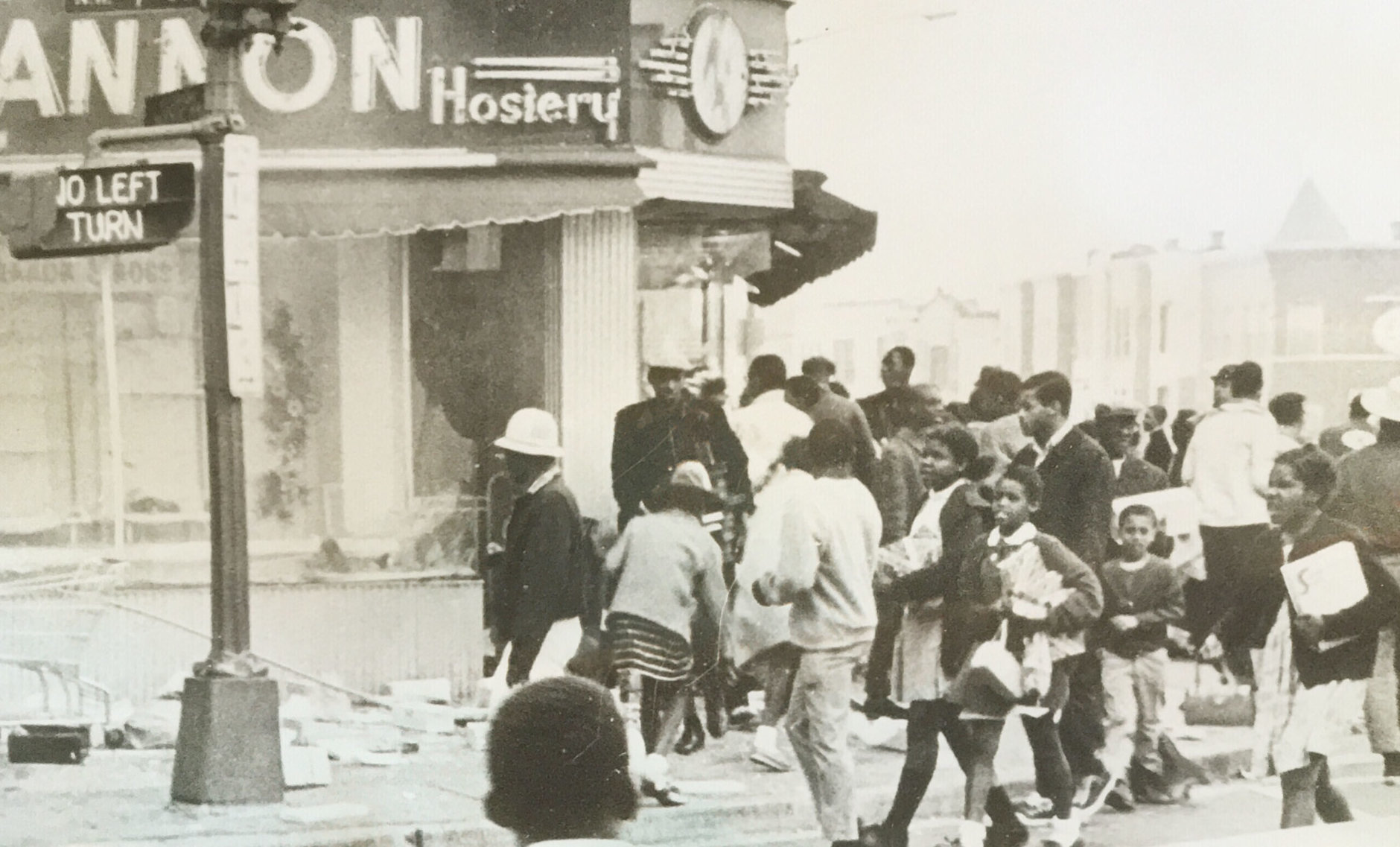

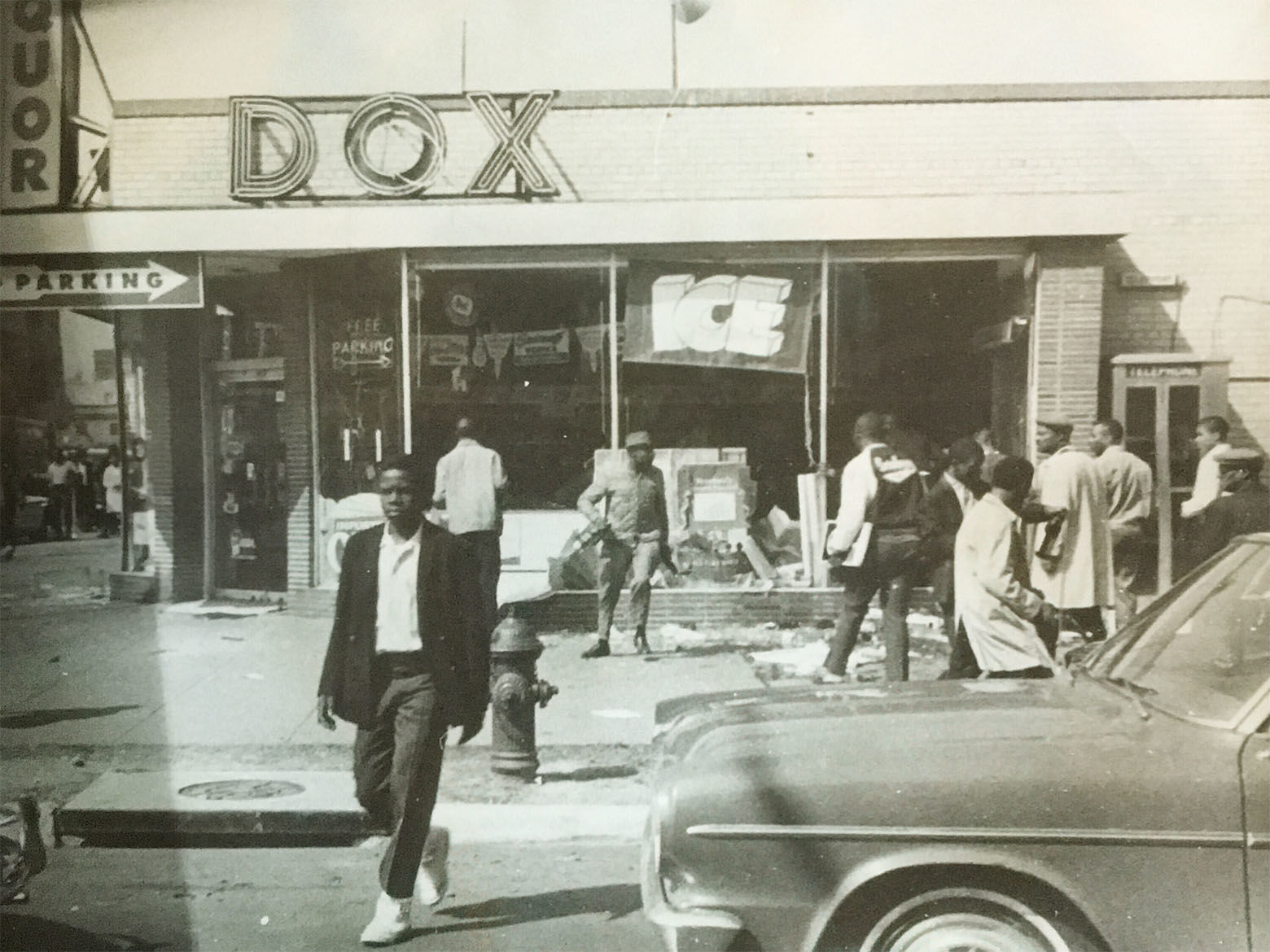

In a few hours, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would be felled by an assassin’s bullet on a Memphis motel balcony. Parts of D.C. would erupt into an outburst of window-smashing, looting and arson. Over the next few days, hundreds of businesses would be torched, parts of neighborhoods would lay in smoldering ruins and 13 people would be killed.

Dennis Hyater was a 26-year-old officer with D.C.’s Metropolitan Police Department. He was working the midnight shift from what was then the 14th Precinct, in Northeast.

He had awakened late that evening to get ready for work. His radio and TV were silent; his wife was asleep. He was cruising through the city on the way to make roll call when he saw a group of men hurling a trash can through the front of a liquor store.

“And I’m saying to myself, ‘What in the … ?’ So I stop my car,” Hyater recalled. “And I get out. My hand’s on my gun.”

Hyater was a black officer in a department that was nearly 80 percent white — in a city still bitterly divided by race. He had no idea similar scenes of looting and vandalism were being repeated all across the city. It was before smartphones, text messages and Twitter — and he hadn’t yet heard the news out of Memphis.

Souder, Hyater and nearly a dozen other retired firefighters and police officers shared their memories with WTOP for the series “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 riots.” This article is based on their accounts.

‘A still came over the room’

In the fire department dispatch center, the TV was on when the news bulletin hit the airwaves about 7 or 8 that evening: Dr. King killed in Memphis.

“And kind of a still came over the room,” Souder said.

Things remained calm at first, he recalled. But then, the reports — mostly concentrated in Columbia Heights — began rolling in.

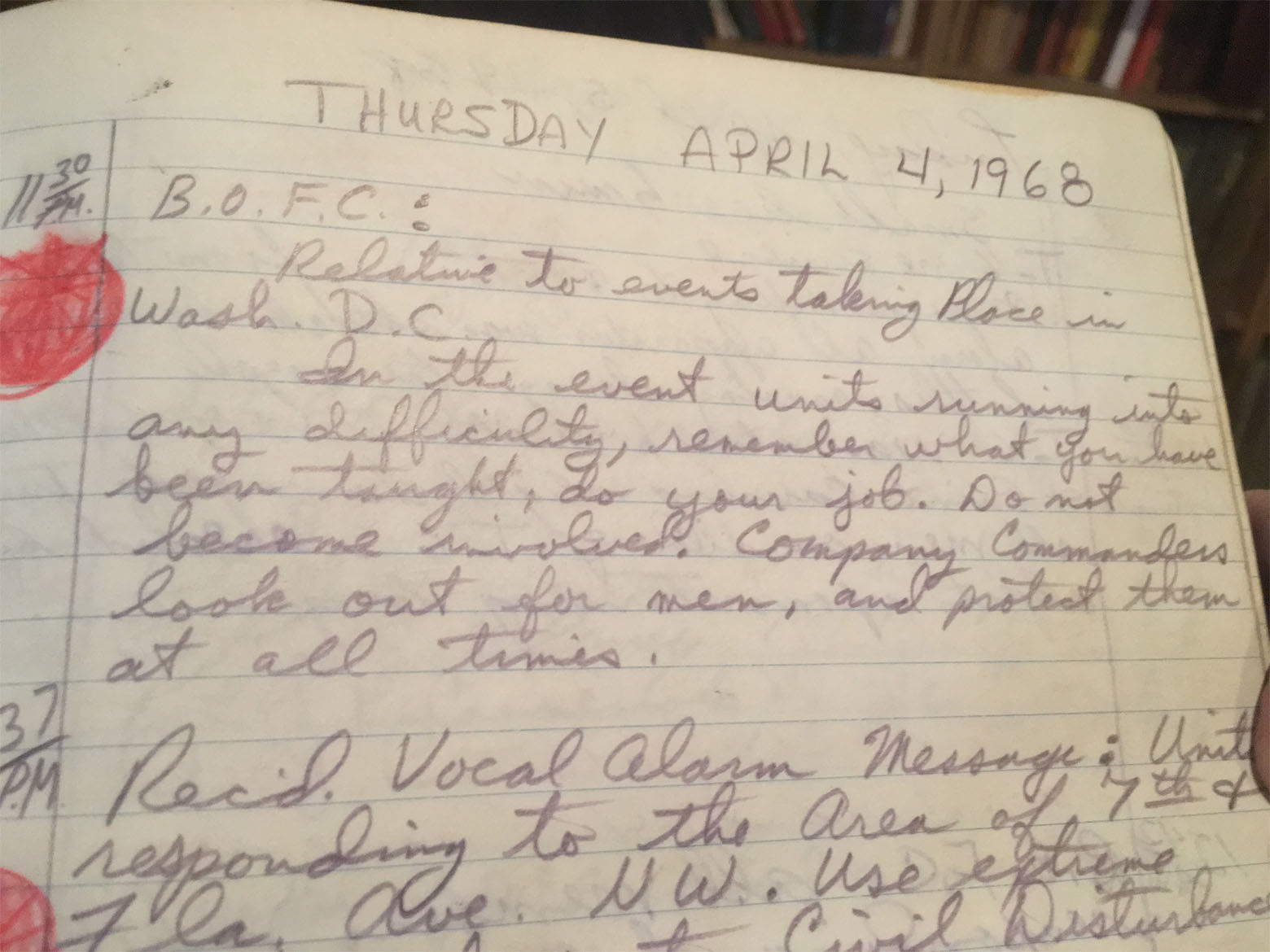

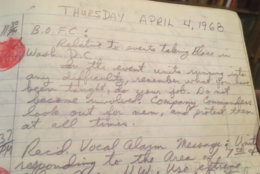

Log books for the fire house on Park Road, which are stored at the D.C. Fire and EMS Museum, detail exactly when and where the fires began spreading.

A dumpster fire at 14th Street and Florida Avenue. A car overturned and set ablaze in the middle of the intersection at 14th and Belmont. Several cars set on fire at the Addison Chevrolet — one of several car lots that used to line 14th Street.

Shortly before midnight, Fire Chief Henry Galotta decided to put “Plan F” into effect. All 1,400 men on the department were called back into service, half working days and the other half working nights.

The log books then record a message from the chief: “Remember what you have been taught. Do your job … Company commanders, look out for the men and protect them at all times.”

The list of fires fills page after page.

‘People were acting out of anger’

At the liquor store, Hyater approached the shattered storefront. “Everybody get on the floor!” he shouted. The men complied, and the officer went to the nearby police call box at the curb to report the burglary.

“I said: ‘Send me a wagon. I got 10 people in here, all broke into the liquor store,’” Hyater recalled. “So the guy said, ‘Have you heard?’ … And that’s when I was told that Dr. King had been assassinated. He said, ‘Man, they’re breaking into liquor stores all around here … ‘Send ’em on their way, secure it as much as you can and come to work.’ And that’s what I did.”

The outbreak of violence on D.C. streets was traumatic, Hyater said. “People were acting out of hate They were acting out of anger. And when the messenger” — King — “was killed, they saw no hope.”

Well before the outbreak of violence spurred by King’s death, there had been tense relations between black residents and police officers.

“The D.C. white policeman is seen by the majority of black citizens in their communities as the perpetrator of violence rather than as the protector of peace,” the Black United Front said in a statement later that year calling for citizen oversight of the police department.

In D.C., segregation hadn’t been the law of the land for some years. But that didn’t mean indignities and injustices weren’t visited upon the city’s black citizens daily, sometimes at the hands of authorities.

Change had been slow to come inside the police department, too. Black and white officers had only recently started patrolling together in the same cars. Black officers were still routinely dispatched only to “black areas” of town, and the few black officers called to assist white citizens were sometimes directed to the back door, Hyater said.

Hyater was angry and disappointed when he found out King had been killed. But he had a job to do.

“I worked that whole night,” he recalled. “As a matter of fact, not only did I work that whole night; I worked the following day and the following day. We put in triple time … We had to come in and deal with what we had to deal with.”

The second day: ‘Baptism of fire’

Police had been overwhelmed and outnumbered that first night. But by dawn Friday, quiet returned.

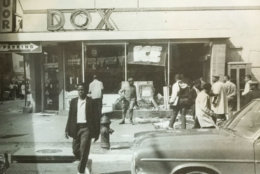

The rash of window-breaking and looting seemed to have burned itself out — as had most of the fires set overnight, thanks to a midnight rain shower. Authorities assessing the situation Friday morning thought they had dodged a bullet.

But around noon, the semblance of calm was shattered.

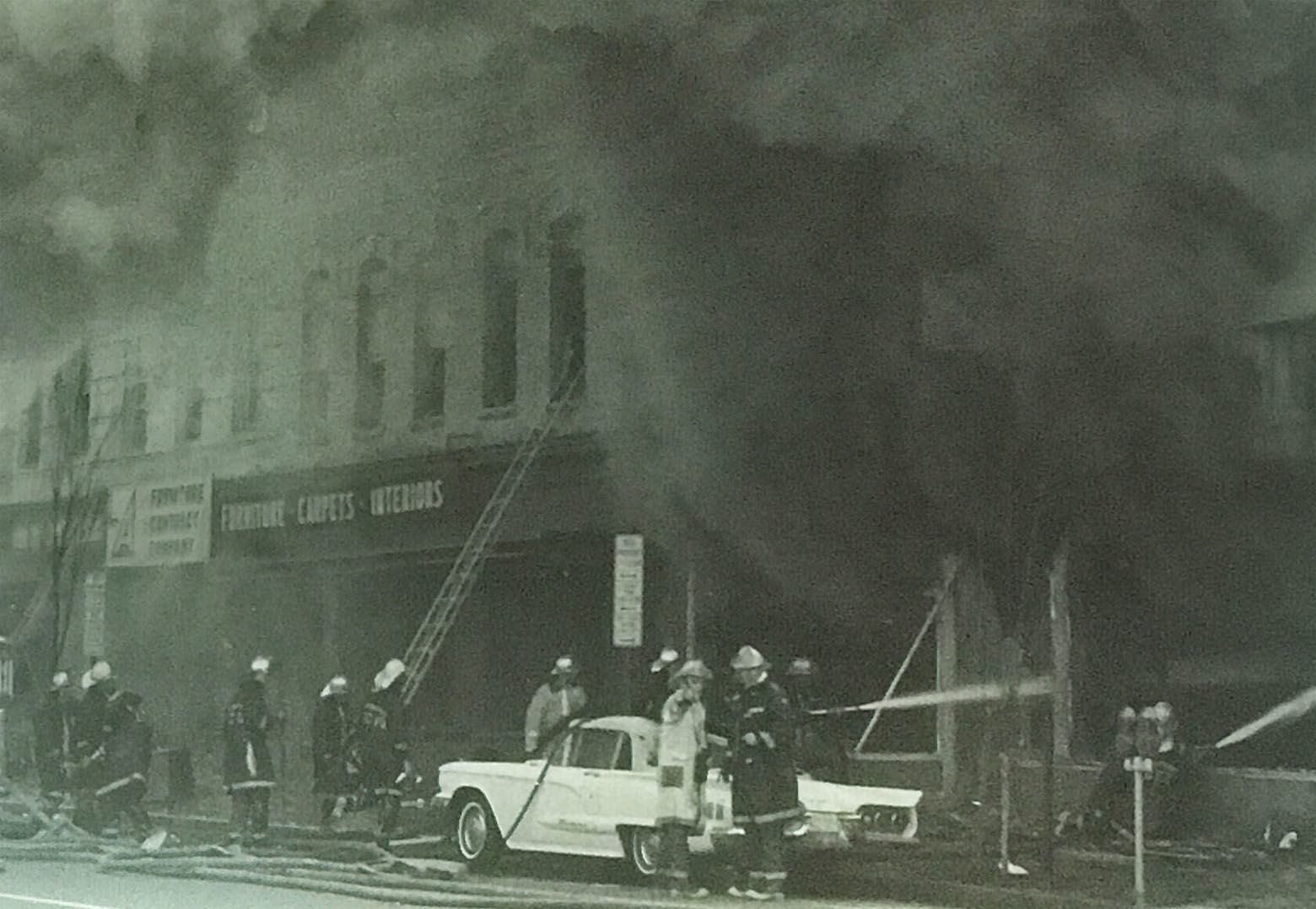

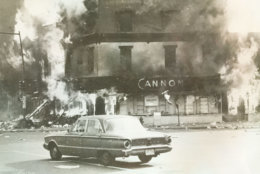

The fires that had started in busted-out stores in Columbia Heights then spread to 7th Street and H Street in Northeast. In clear daylight, fires blazed out of control, sending plumes of black smoke over the nation’s capital.

Souder, who had slept on the floor in the communications division, was back at the switchboard.

Department officials would later estimate an average of 25 to 30 new fires were breaking out every hour that Friday afternoon.

“It really was my baptism of fire,” Souder said.

Out on the streets, firefighters were stretched thin. Because crews were battling so many blazes at the same time, they weren’t able to make sure all the fires were really out before moving on to the next one. Hundreds of fires rekindled over the next few days, adding to firefighters’ grueling workload.

And they suddenly found themselves the target of people’s anger and frustration. Hostile crowds lobbed bottles, rocks, bricks and paint cans at the men responding to fires.

Firefighters were stunned by the hostility. They were used to be greeted as heroes. They literally ran into burning buildings to save people. But in the charged atmosphere after King’s killing, the majority-white department became part of “the system.”

At the time, fire trucks had open-air cabs. After the riots, the fire department would install protective plywood coverings and caging on all fire trucks.

‘It has to be your life or someone else’s life in danger’

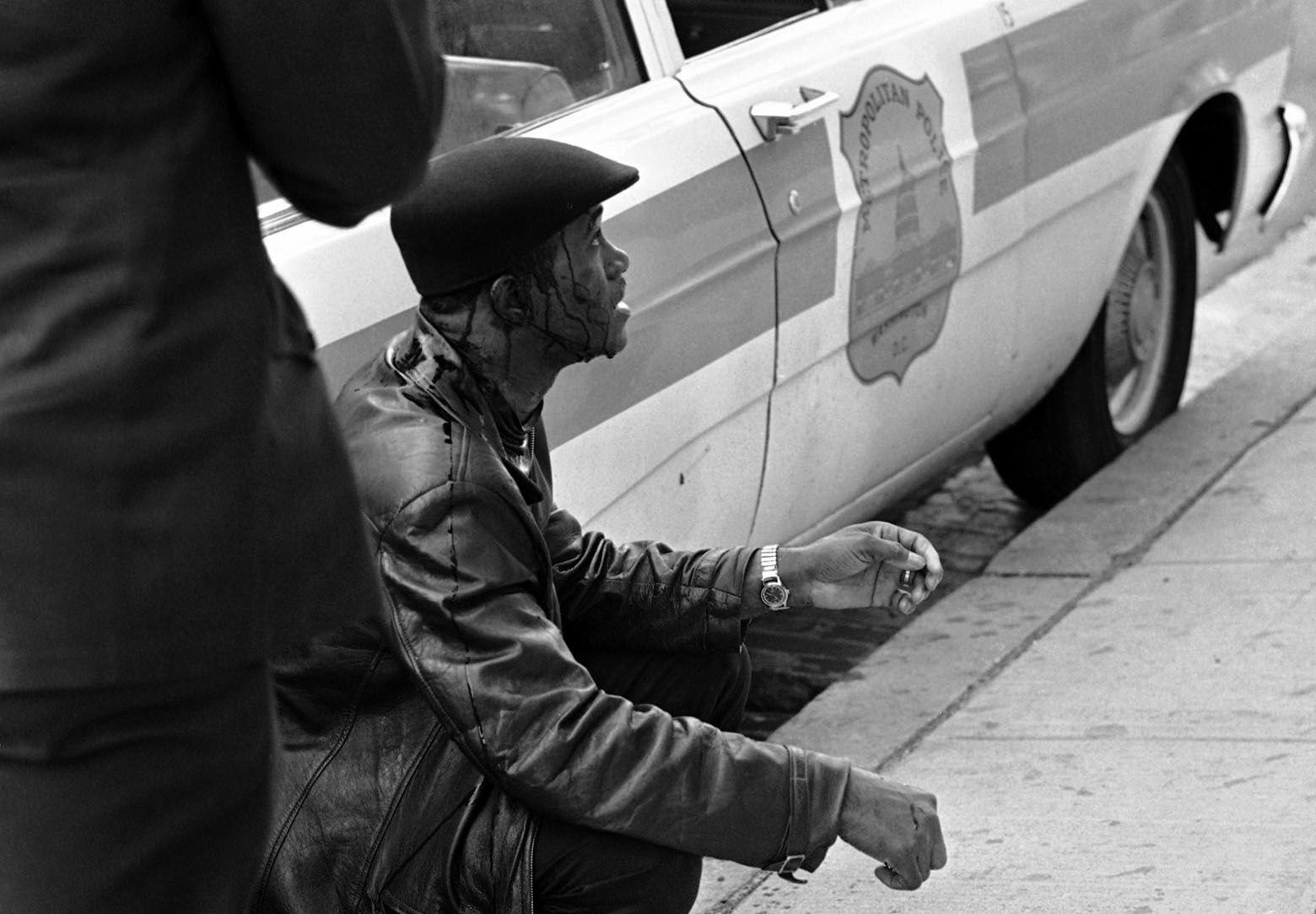

Over the weekend, the police response to the rioting turned deadly. In two separate incidents, police shot two young men, both black: 15-year-old Thomas Williams and 20-year-old Ernest McIntyre.

A coroner’s jury — essentially an inquest — later ruled Williams’ shooting an accident, a determination disputed by an eyewitness. McIntyre’s shooting was ruled a not-justified homicide, but a grand jury declined to indict the officer.

At the time, police regulations authorized officers to shoot at fleeing felons if all other means of capture had been exhausted. However, during the riots, authorities were under orders to use the minimum force necessary — interpreted to mean only in self-defense — even it that meant more looters ransacked stores. Merchants and business owners denounced the policy, but it likely saved countless lives, the City Council concluded in a report on the handling of the unrest.

“One of the things that I remember distinctly being told was, ‘Make sure that you use good judgment when you’re out there,’” Hyater recalled. “‘Remember, it has to be your life or someone else’s life in danger.’ That’s all that had to be said.”

Hyater never fired his weapon. He was lucky, he said.

“Before I knew that Dr. King had been assassinated, and I found these guys in the liquor store, I could’ve shot someone,” Hyater said. “I didn’t know what was going on … I think if I felt my life was in danger, I would’ve used force.”

“So there for the grace of God, go I,” he added.

After the riots, Hyater continued rising through the ranks even as the department — and the city — faced tough times.

Crime spiked in the 1970s, and parts of the city were ravaged by the crack epidemic in the decade that followed.

Hyater became a deputy commander and then a lieutenant. During the early 1990s when D.C. earned the dubious moniker “Murder Capital,” Hyater oversaw a special unit to work on several of the city’s most high-profile unsolved killings. He retired in 1992 after 28 years on the force.

Hyater, now 75, works at the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies, a group that reviews police departments’ policies, including the use of force.

‘My fate was to be where I was’

In the early morning hours, as Sunday turned to Monday,the fire dispatch board Souder had been running since the riots broke out, finally showed “clear” — no units were on the street responding to calls.

In that time, the fire department had responded to more than 1,200 fires, according to an internal report published later that year detailing the department’s response. All told, about 470 buildings were involved in fires, including dozens of houses, the fire department reported. A fire had been set in a Southeast school, and two fires were reported in the children’s ward of D.C. General Hospital.

Of the 13 deaths during the riots, eight were listed as fire-related. Hundreds more people were injured — most not seriously, including nearly 40 firefighters.

When he finally got a chance to go home, Souder hitched a ride in an Army Jeep down 14th Street. Souder had dispatched trucks to hundreds of fires across the city, but it was the first time he saw the devastation with his own eyes.

For Souder, now 78, his trial by fire turned into a career.

He ended up staying in the communications section for the rest of his career with the department. He retired in 1985 and went on lead 911 operations in several counties in the D.C. suburbs. In 2001, he was the director of 911 in Arlington County when Flight 77 slammed into the Pentagon.

Reflecting on his experience in 1968, Souder said: “If you’re a firefighter, you want to be where the action is,” he said. “If something’s going to happen, you want to be there and do your best in helping to make it better. That was not my fate that time, to be in the field. My fate was to be where I was.”

More from the series, “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.”

- ‘Everything was on fire’ — remembering the DC riots 50 years later

- DC Uprising: An oral history of the 1968 riots

- Under fire: Retired police, firefighters remember 1968 flashpoints

- ‘The mayor saw it with his own eyes’ — a reporter chronicles 1968 chaos

- After the riots, an activist on trial

- How Ben’s Chili Bowl survived the 1968 riots to become a DC landmark (VIDEO)

- Shattered lives, unanswered questions 50 years after the riots

- Small DC church survived the riots. But then came the wrecking ball. Finally, a rebirth

- Then & Now: Powerful images show 1968 riot damage and rebuilt DC neighborhoods