This story is part of the WTOP series “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.” Each day this week, we’ll tell the stories of the upheaval and tumult 50 years ago through the eyes of those who experienced it.

WASHINGTON — On the second night of unrest in D.C. following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Rufus Mayfield hit the streets.

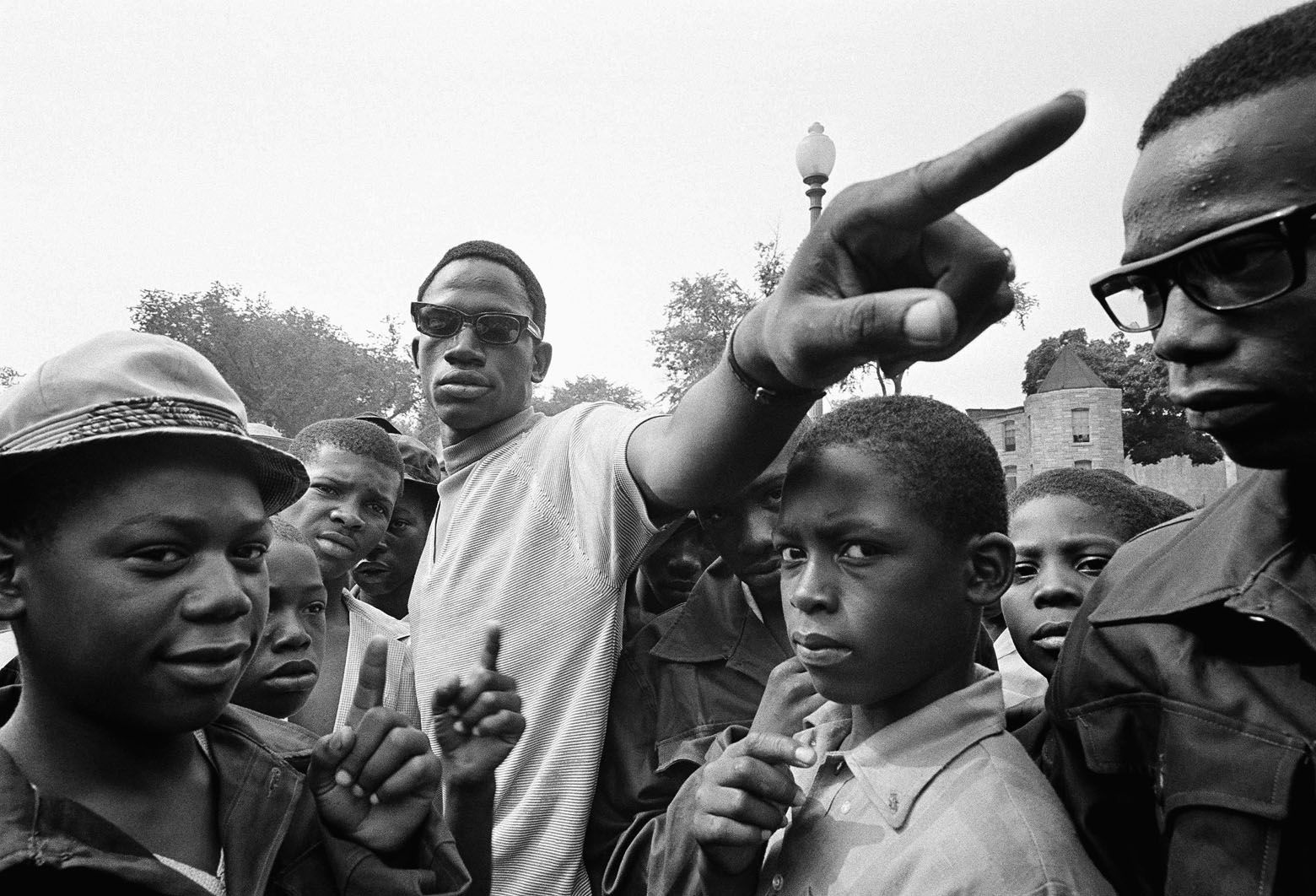

The 21-year-old community activist — known to friends, congressmen and in the pages of the local newspapers as Catfish — was patrolling the streets telling kids to “cool it,” the local papers reported.

In the District, King’s killing sparked days of destruction. Fueled by frustration and rage — and opportunism — looters kicked in storefronts, plundered shelves and set ransacked stores afire. Federal troops were called in and Mayor Walter Washington ordered a curfew.

Mayfield had been given one of the cards handed out to city officials and community leaders allowing them to be on the streets past the curfew. The “flamboyant leader of ghetto youth,” as a newspaper profile described him at the time, was seen as a voice young people would heed.

The evening before, the D.C. native had been giving a talk before a student group at Indiana University when someone came bursting into the hall shouting that Dr. King had been killed.

Mayfield hopped on a plane headed back to D.C.

“And when I flew into National, the place just looked like someone had dropped a bomb,” he recalled. “The smoke, that dark smoke, was just billowing up.”

Later that night, Mayfield would see a D.C. police officer fatally shoot a teen boy running out of a looted store in Southeast. He would dispute the officer’s account of what happened leading up to the shooting. But months after the riots, it would be Mayfield on trial.

WTOP sat down with Mayfield for the weeklong series “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.” This story is based on Mayfield’s recollections as well as newspaper coverage of his career in activism as covered in The Washington Evening Star.

A shooting outside the Young Men’s Shop

Mayfield knew the frustrations faced by black youth in D.C. well. But as unrest rocked Washington in the days following King’s death, he said he was dismayed by what he saw.

“How do you go and pillage a store because Dr. King was killed?” he said. “Look at who he was … I would be telling them, ‘Man, put this stuff back. You are devaluing him.’”

On the evening of April 5, 1968, Mayfield was in Northeast D.C. near a store called the Young Men’s Shop, where a crowd had gathered. A group of kids ran out of the store. A police officer, with his gun drawn, had stopped one of the teens when 15-year-old Thomas Williams ran past and bumped into him, the officer said, causing the gun to go off, killing Williams.

Mayfield saw something different. Williams had already run past the officer and was several feet away when the officer fired, he said.

Mayfield was called to testify against the officer during an inquest. Some witnesses backed up the officer’s account. An FBI expert said tests showed the boy was only about 6 inches from the officer when he was shot.

The shooting was ruled an accident.

As it turned out, this wasn’t the first shooting at the hands of a police officer Mayfield had witnessed on Minnesota Avenue.

The first one propelled his launch into activism.

‘I didn’t know what else I could do’

Mayfield grew up in the Parkside projects in Northeast D.C. His nickname, Catfish, was an inheritance from his father, an avid fisherman. His mother worked as a maid — in the White House.

Mayfield grew up a hell-raiser.

Before his 16th birthday, he had racked up a prolific juvenile record for stealing cars. He spent two years at the Lorton Youth Center and did a year at the National Training School.

In May 1967, a D.C. police officer fatally shot 19-year-old Clarence Brooker, a friend of Mayfield’s, after an altercation over a package of cookies that had been tossed on the ground. The officer, who was white, was attempting to arrest Brooker behind the post office on Minnesota Avenue in Northeast on a disorderly conduct charge. A struggle ensued. The officer said he and Brooker were tussling over the officer’s gun when it went off.

But Mayfield and other witnesses disputed that account, saying Brooker had broken free of the officer and was running away when he was shot in the back.

The bullet went in so cleanly that no one, at first, knew Brooker had been shot.

“And one of the … things that has always haunted me is when he was sitting in the back of the police car, he was just looking at me: ‘Why didn’t you help me?’” Mayfield recalled. “I didn’t know what else I could do.”

After booking Brooker into the 14th Precinct, officers discovered a “small bloodless bullet hole,” The Washington Star reported the next day. Brooker was rushed to the hospital where he died 30 minutes later.

“I was devastated,” Mayfield said.

Then, he turned to action.

Brooker was one of 17 people fatally shot by authorities in D.C. throughout 1967 and 1968, according to a 1968 tally by The Washington Post compiled by the paper amid growing uproar over the increasing number of people — mostly black — shot to death by police. Mayfield marched on City Hall and held sit-ins, pressing for a government probe of the shooting and calling for more citizen control of the police department.

More provocative street protests soon followed. A friend lent Mayfield a hearse, and he hoisted an empty casket to the top.

“And I had all these young black brothers … marching behind the casket and stuff,” Mayfield recalled. “And it was a symbol of my friend being murdered by this police officer.”

The coroner declared the killing a justifiable homicide. But in part because of the attention heaped on the case, the U.S. attorney brought it to a grand jury, which heard 20 witnesses over three exhausting days of testimony.

The grand jury declined to indict the officer.

‘Call it Pride, Incorporated’

Mayfield’s ostentatious protests drew the attention of another young activist in the city: Marion Barry.

The future leader who would eventually be called “mayor-for-life,” Barry had moved to town amid a wave of leaders from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee who came to the nation’s capital with ideas of transforming activism into real political power.

Mayfield and Barry met at the tail end of the “long, hot summer” of 1967, when the inner cities of Newark, Chicago and Detroit went up in flames. Officials in D.C. were looking for a way to stave off similar unrest.

Mayfield, Barry and a handful of other activists came up with a summer work program.

The U.S. Labor Department awarded them $300,000 to launch a pilot program for unemployed, trouble-prone youth from across the District. The program was called Pride, Inc.

“I mean, this never, ever happened: Northwest, Southwest, Southeast. What really was the glue was Pride,” Mayfield recalled. “And how it got the name Pride is because I kept talking about pride in our young black kids. So they said, ‘What are we going to call the organization?’ I said, ‘Call it Pride, Incorporated.’”

The members wore dark green jumpsuits that would become a badge of honor. For $1.75, they cleaned alleys, swept streets, mowed lawns and exterminated rats.

The group’s work caught the eye of Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who joined Catfish for an alley sweep one summer day. Soon, Mayfield was testifying in Congress and receiving letters and telegrams from all over the country.

He had his critics, though. Rep. Joel Broyhill, a Northern Virginia Republican who unashamedly supported segregation into the 1960s and who opposed Pride’s funding, constantly cited Mayfield’s criminal record in press interviews, referring to the youth leader as an “uneducated hoodlum.”

But there was no doubt the charismatic Catfish was a star.

After the first month of its existence, Pride, Inc. had cleaned up 1,400 streets and exterminated an estimated 10,000 rats, according to a 1967 Star report. The Labor Department was ready to extend the program — and cut a $1 million check to do so.

That’s when Mayfield and Barry had a falling out.

“Everything was fine when we had the $300,000,” Mayfield recalled. “Everything changed when we got the million.”

Barry, the politically savvier of the two, was ambitious. He perhaps had his eye on higher office even then. Mayfield, on the other hand, never stopped believing in “the cause.”

“What the system wanted to do — if they gave you money, that money should placate you … I kept pushing,” Mayfield said. “And Marion could not take the pushing that I was doing.”

Mayfield and Pride parted ways at the end of 1967.

On trial

Several months after the April riots, Mayfield was visiting a friend’s house, listening to the radio.

By that point, he was a free agent. He was still touring colleges all across the country, and he had a syndicated column called “Voice from the Ghetto,” which appeared in newspapers in Minneapolis, Chicago and Miami. He’d also had few minor brushes with the law. He was brought up on speeding charges — he was going 9 mph over the speed limit; driving on a suspended license; and faced a minor marijuana possession charge.

Still, he wasn’t prepared for what he heard next.

“I’m sitting there and the news on the radio says, ‘Flash, Rufus Mayfield has just been indicted for interfering with a police officer during the riot.'”

The indictment stemmed from an incident at a liquor store on Minnesota Avenue at the height of the unrest during the April riots — a few hours before he witnessed the shooting at the Young Men’s Shop.

Two police officers said Mayfield, leading a group of about 40 bottle-wielding youths, had surrounded the store and coerced them into letting a looter go free.

Mayfield maintained he was there to help.

“I showed them the card that they gave us,” he recalled. “I said, ‘Look, my name is Rufus Mayfield and here’s my card to be out here to assist y’all.’”

He said the crowd had already gathered when he showed up and was quickly turning hostile. He said he helped cool things down by asking officers if they would let the man go if he left the stolen liquor behind.

Mayfield faced five years in prison. The U.S. Attorney’s office never explained why it waited six months to bring charges.

By that point, Mayfield had made a name for himself doing things his way. Still, he managed to ruffle feathers once again when he decided to defend himself against the charges.

Mayfield had an unorthodox way of preparing for the September 1969 trial.

“This is what I did, I kid you not. Every night, I would look at ‘Perry Mason,’” he said, referring to the classic TV legal drama.

The trial was unusual in other ways. One juror kept falling asleep, eventually leading to his removal.

Finally, the closing arguments came. The prosecutor took five minutes.

Mayfield spoke for an hour. “In the eyes of God, I am innocent,” he said, according to The Star. He asked the jury to return a not-guilty verdict, “so I can continue to carry the torch.”

The jury deliberated for less than an hour before Mayfield was called back into the courtroom.

The verdict: Not guilty.

‘What happened to Catfish’

Once his court battle was over, Mayfield felt relief, he said. But then sadness set in. The legal burden had been lifted, but he was still mourning the loss of his partnership with Barry.

He enrolled at George Washington University on a scholarship in the early 1970s, but left after a year to work on rallying support for the constitutional amendment lowering the voting age from 21 to 18.

He got a radio show on WOOK called “Catfish is Here,” because “everybody wanted to know what in hell had happened to Catfish,” he said. He parlayed the radio gig into a career as an emcee and then started doing stand-up comedy. It was a way to put his sharp tongue to use and to channel his anger.

Then he joined the D.C. city government.

In the mid-1980s, he was hired by Barry, who was then serving his second term as mayor — and with whom he had reconciled, to work in the Department of Human Services. He was fired by Mayor Sharon Pratt Kelly in the 1990s after she took over and sought to clean house. Finally, he was rehired by the Anthony Williams administration, to whom he gives the lion’s share of the credit for modernizing city services.

Mayfield retired in 2007. He lives in the same Southeast D.C. row house his parents bought in 1959. The block has recently seen an influx of new residents. Many of the row houses are under renovation.

These days, Mayfield has lost none of his fervor, though his righteous fury is now cut with more than a little resignation. Amid D.C’s newfound prosperity, the problems of poverty and lack of opportunity seem to be shunted to the side.

Political leaders in D.C. seem clueless, he said. And what happened to the rabble-rousers, the agitators, the troublemakers — the Rufus Mayfields? — he wondered.

He said he was inspired recently by the schoolchildren in Florida who have led the call for stricter gun control measures in the wake of the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in which 17 students were gunned down. Last month, the March for Our Lives brought hundreds of thousands of supporters to Washington, one of the largest protests here since the Vietnam era.

“That’s what I’m talking about,” he said. “They’re young’uns. Teenagers. The fire that’s in their eyes when they talk… Where are those within our community?”

More from the series, “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.”

- ‘Everything was on fire’ — remembering the DC riots 50 years later

- DC Uprising: An oral history of the 1968 riots

- Under fire: Retired police, firefighters remember 1968 flashpoints

- ‘The mayor saw it with his own eyes’ — a reporter chronicles 1968 chaos

- After the riots, an activist on trial

- How Ben’s Chili Bowl survived the 1968 riots to become a DC landmark (VIDEO)

- Shattered lives, unanswered questions 50 years after the riots

- Small DC church survived the riots. But then came the wrecking ball. Finally, a rebirth

- Then & Now: Powerful images show 1968 riot damage and rebuilt DC neighborhoods