This story is part of the WTOP series “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.” Each day this week, we’ll tell the stories of the upheaval and tumult 50 years ago through the eyes of those who experienced it.

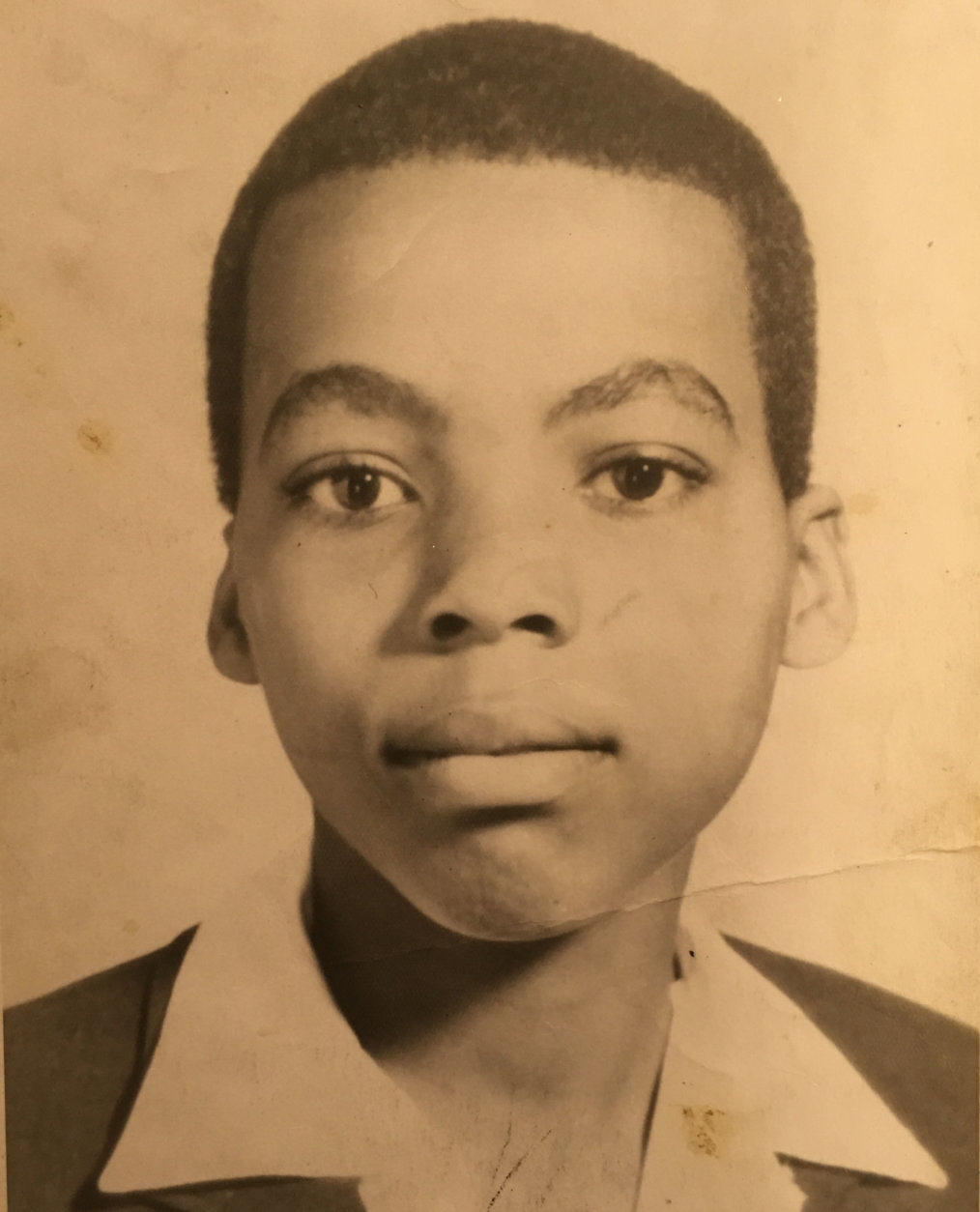

WASHINGTON — Amid the unrest that engulfed D.C. following the killing of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in April 1968, 15-year-old Vincent Lawson vanished.

The Dunbar High School freshman was at his grandmother’s house around the corner from H Street, where entire blocks of stores were looted and burned after King’s death. Vincent had called home to his mother on East Capitol Street, and she begged him to stay inside. But he and his older brother slipped out.

Vincent never came home.

In 1971, construction workers preparing to demolish a department store warehouse on H Street — damaged by smoke and heat and boarded up after the riots — discovered a skeleton inside. It was Vincent’s.

In the three years between her brother’s disappearance and the discovery of his body, her family fell apart, said Vanessa Lawson Dixon, who was 13 when Vincent vanished.

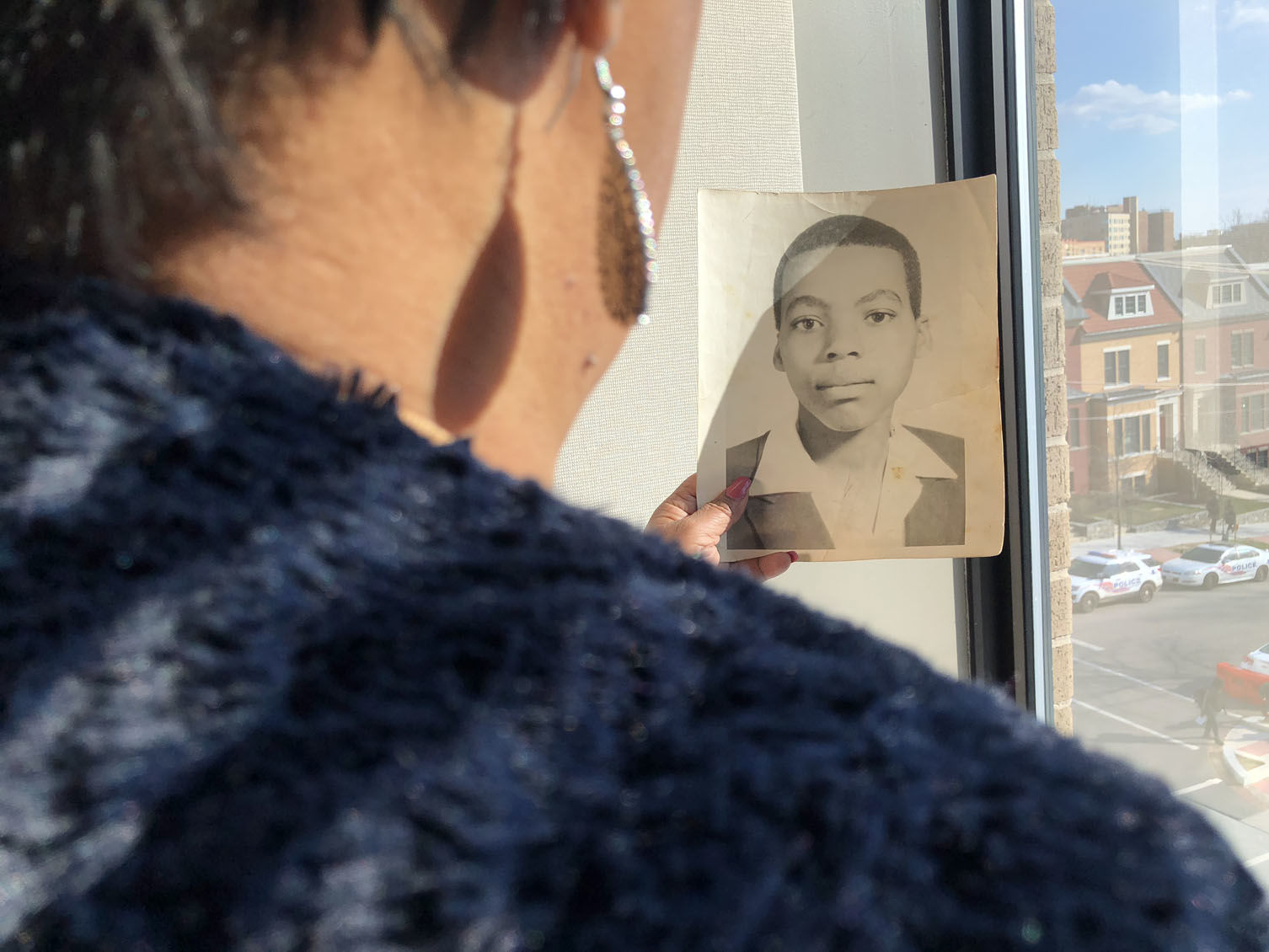

Fifty years later, closure is elusive and she wonders whether the D.C. government really did all it could to find her missing brother.

“That boy was found three years later, two blocks from my grandmother’s house and he was there all that time,” said Dixon, now 62, in an interview with WTOP for the weeklong series “DC Uprising: Voices of the 1968 Riots.”

There are nagging questions about other victims of the 1968 riots. Two bodies pulled from burned-out buildings after the uprising — described as charred beyond recognition but believed to be young men — stayed in the city morgue for years as John Does. They were eventually cremated. Fifty years later, no one knows who they were, or whether they’ll ever be identified.

‘Don’t let him back out the house’

The Lawsons’ ordeal started when Vincent and his older brother, Glen, set out for their grandmother’s house near H Street amid the violent aftermath of King’s killing, which had shocked the nation and sparked unrest in D.C. and cities across the country.

Vincent was the youngest of the three Lawson boys. He was slight for his age, with a big head, so everyone called him “Egg.” He was a good kid — the neighborhood’s kid brother.

Vanessa, the youngest of the Lawson children, wasn’t much for dolls. She kept up with the boys and was especially close to Vincent, who was only two years older.

“He was my best friend. We grew up together, like two peas in a pod,” she said. “He and I were like twins.”

The two were always doing odd jobs throughout the neighborhood — raking leaves, shoveling snow, carrying people’s groceries home in a little red wagon. They earned enough to afford a fresh pair of sneakers from Shoe Town almost every other week, she said. High-top Chuck Taylors and Bob Cousys were their favorites.

Their parents had divorced a few years before, and the Lawson children lived with their mother, Ida, in “the projects” on East Capitol, Dixon said. Their mother worked as a housekeeper. Their father, Prentiss Lawson, a Postal Service supervisor, had remarried and lived across town.

They weren’t poor, Dixon said — they were managing. Still, their mother pinched pennies. She would always buy individual pairs of stockings instead of the whole box when the family went shopping at Morton’s on H Street, one of the local department store chains that used to dominate D.C.

“My brother said, ‘Why don’t you just buy the whole box?’” Dixon recalled. “And she would say: ‘I can’t afford it. I only need two pair and I’ll buy some more when I get paid next time.’”

When the rioting and looting hit Northeast, crowds there broke into the Morton’s at 6th and H. Vincent apparently slipped inside with some of his friends. Later that day, he called home from his grandmother’s.

“He got on the phone and he told her: ‘Mom, I went into Morton’s, and I got you three boxes of those stockings! I got the whole box,'” Dixon recalled. “Oh my God, it brings chills to me now to think about … He told her he got her three boxes of stockings, and she wasn’t going to have to worry about that anymore. And she told my grandmother, ‘Don’t let him back out the house.'”

‘He’s gonna be home any day now’

When Vincent was missing, the family tried nearly everything to find him. Dixon’s father filed a missing persons report with D.C. police — Vincent was missing person No. 275 in the D.C. police files — and also paid a private investigator $500 to try to track him down.

Both the investigator and police department assured the Lawsons that Morton’s properties — where Vincent was last seen with his friends — had been checked thoroughly before being boarded up in the aftermath of the riots, Dixon said. He just hadn’t been found.

For years, Dixon was haunted by phantom sightings of Vincent. Riding the bus, she’d think she spotted him walking down the street and would race off the bus to chase him down.

“I thought, ‘There he is!’ Excitement, adrenaline, heart about to come out of my chest,” she recalled. “Within 10 seconds, I’m like, ‘I’m gonna be the one to bring him home!’”

It was never him.

“You want something so bad that you think you see it,” Dixon said. “You make it be what you want it to be.”

Dixon held her feelings inside. “I didn’t know what I was supposed to cry about, because he was just missing … And I went on like, ‘He’s gonna be home any day now,’” she said.

Three years later, the Lawson family got the call everyone had been dreading.

Construction workers had gathered early in the morning on Saturday, July 24, 1971, near the boarded-up Morton’s warehouse, next to the burned-out department store on H Street. Both buildings, heavily damaged in the disturbances that ravaged the neighborhood in 1968, had stood empty ever since.

The workmen were preparing to take off the building’s roof when one of the men lifted up a skylight and saw a skeleton inside, still clothed and lying face down.

13 lives lost, including 2 nameless victims

The majority of the 13 people who died during the 1968 riots lost their lives in fires.

A 56-year-old woman named Annie James was housebound and stuck in bed when a fire broke out in a store below her Seventh Street apartment.

A 40-year-old man, William Paul Jeffers, was killed when a store, damaged by fire, collapsed on him. The Washington Post reported he had gone out looking for work clothes in some of the damaged stores.

Two white men were killed in confrontations with groups of young black men.

George Fletcher, 28, of Woodbridge, Virginia, drove into D.C. with several co-workers late on the evening of April 4, apparently unaware of the unrest in the city. The group said they were accosted by a gang of kids at a gas station on 14th Street, and Fletcher was stabbed in the head.

Fred Wulf, a 78-year-old retired house painter, was beaten by a group of young black men at New Jersey Avenue and H Street in Northwest, witnesses later told police.

Police fatally shot two young black men — 15-year-old Thomas Williams and 20-year-old Ernest McIntyre. McIntyre’s shooting was classified as a non-justified homicide, but charges were never brought against the officer.

Information on the victims of the riots comes from a review of coverage in The Post and The Washington Evening Star.

Authoritative information beyond contemporary newspaper articles is surprisingly hard to come by. It’s unclear whether the D.C. police maintain records going back that far. After responding to an introductory email, police spokesman Dustin Sternbeck did not respond to follow-up emails from WTOP over the course of several months.

Perhaps most unsettling of all: Two of the people who died during the riots were never identified. One body was pulled from the rubble of Morton’s department store — near where Vincent’s bones would eventually be found. The other was recovered from a G.C. Murphy store on 14th Street in Columbia Heights.

Both sets of remains were discovered during the 1968 disturbances or shortly after. They were both described as severely burned black males under the age of 25, possibly teenagers.

The two John Doe remains were quietly stored at the morgue and seemingly all but forgotten for three and a half years, when an item in the The Washington Post — buried in the C section — reported the remains had been sent to D.C. General Hospital to be cremated.

“Either no one was able to or did not bother to identify them,” The Post reported.

It’s unclear why the morgue decided to offload the remains at that time — or why it held onto them for so long in the first place. At the time, the morgue typically only waited a month before turning over unidentified bodies for cremation.

In an interview with WTOP, the current chief medical examiner, Dr. Roger Mitchell, said he’s not sure where the remains would have ended up after they were cremated. In the early 1970s, the department was transitioning from a coroner to a medical examiner, and doesn’t have detailed records for cases before 1973.

Today, blood and tissue samples are taken of all unidentified sets of remains and kept forever. And remains that are never identified are eventually buried, not cremated.

But in the ’60s and ’70s, there were fewer ways to attempt to identify unknown remains. DNA testing, for example, didn’t become a standard part of medical forensics until the 1980s.

“In 1968, DNA would have been just so foreign, it wasn’t something that was conceived of for a coroner to even take in 1968,” Mitchell said. “It would have been outer space for them.”

It’s impossible to say the remains won’t ever be identified, but at this point, there’s nothing in the office files that will help do so, he said.

Any hope of identifying the two John Does from the riots would have to rely on circumstantial or contextual evidence, Mitchell said, such as someone coming forward who saw someone going into one of the buildings that burned during the riots.

“That would be probably the best we would be able to do,” he said.

The what-ifs and the unknowns

For the Lawsons, the discovery of Vincent’s remains answered some, but not all, of their questions. And the passage of time hasn’t quieted the nagging torment of the what-ifs, the unknowns, the little details that just don’t seem to make any sense.

In addition to dental records, the skeleton was identified as Vincent’s by the clothing — a maroon-and-gray striped sweater and dungarees. Dixon’s father recognized the sweater as one Vincent had received the previous Christmas. A small medallion with the initials V.L. was also found near his bones.

Because his clothing was still intact, authorities surmised the boy had likely died of smoke inhalation. But the medical examiner told reporters the official cause of death was unknown and would probably remain that way because all of the flesh had fully decomposed.

For Dixon, some of the details don’t add up.

The skeleton was missing two front teeth, according to one newspaper report. But her brother wasn’t missing any teeth, she said. And the shoes he was found in — low-top sneakers — weren’t the kind he always wore.

At times, Dixon is still wracked by doubt. Could his body have been mixed up with the unidentified remains pulled from the burned-down Morton’s? One of the friends who was with Vincent the night he disappeared said police were chasing them out of the store with guns drawn when they lost track of him, she said. Could he have been shot?

The medical examiner told The Post the skeleton had no broken bones or apparent gunshot wounds to the skull.

Dixon said she doesn’t recall whether the family ever received a death certificate or medical examiner’s report. Her father, who died two years ago, was a meticulous record-keeper, she said, and she hasn’t been able to find anything in his personal files.

Still, Dixon said most of the time she is able to come to terms with what authorities said was the most likely scenario: Vincent was overcome by smoke in the warehouse and died of smoke inhalation.

“I’m trying to make myself believe that he died quickly,” she said.

One thing is certain in her mind: He could have been found sooner.

All the time Vincent was missing, the police had assured the family that Morton’s — the last spot the missing teen was spotted — had been thoroughly checked, she said.

“They were emphatic about it. The D.C. government was emphatic about it. And they all lied,” she said. “They all lied, because he was found within minutes of the construction workers taking the boards off of the building and going in there … How dare you think that it’s OK to just sweep this under the carpet like that.”

After her brother’s remains were found, Mayor Walter Washington quietly paid a visit to the family and brought a turkey dinner, she recalled. But she said the city never publicly acknowledged any missteps in the handling of her brother’s case — or apologized.

“If that building would’ve been checked from top to bottom … They would’ve found him, dead or alive,” Dixon said. “They would have had a body. They would’ve had him intact. And we could’ve had a homegoing. We could’ve had a funeral. We could have had a repast. Everybody could’ve had an opportunity to share their emotions and express themselves. And those are things you need to do. But we had to hold it in for all these years, because we didn’t know.”

After Vincent disappeared, Dixon’s mother’s nursed her grief with alcohol.

“My mother went through something that I didn’t understand during that time,” she said. “She had other kids, but she was like a zombie … She was missing her son.”

Almost a year to the day after the discovery of her brother’s bones in the Morton’s warehouse, Dixon’s mother died. The official cause was cirrhosis of the liver. For Dixon, it’s clear her mother died of a broken heart.

‘There’s no grave site … There’s nothing.’

After Vincent’s remains were recovered, a minister affiliated with the city government convinced the family to forego a funeral or memorial service and let the city handle disposing of them, Dixon said. She was 16 years old at the time. She assumes her father must have given the OK, but she said she has no idea who the minister was.

“All I know is, we didn’t have a memorial,” she said. “We didn’t have a cremation that we took part in … It happened so fast. And I remember my mother being mad, fussing and cussing because she wanted his remains and she never got them. She never got his remains.”

For Dixon, there’s no place for her to go to remember her brother.

“There’s no grave site. There’s no memorial site. There’s nothing,” she said. “I have no place to memorialize my brother.”

Even H Street doesn’t look the same anymore.

The past 50 years have seen the complete revitalization of the once riot-torn corridor. High-priced condos and cocktail bars have sprung up where once stood only boarded-up buildings and empty lots.

Dixon prides herself on being a “tough cookie.” She’s had a successful life, she said. She was married, had three children and is now a grandmother. She worked for several years as a program manager for the Federal Aviation Administration and retired four years ago after 39 years with the federal government.

“I held my own,” she said.

But the long years of waiting for her brother to come home and then finding his body in the store around the corner “changed everything else about my family,” Dixon said.

This year, Dixon wanted to give her brother the memorial he never had. She checked with churches near H Street about holding a small service but never heard back. She wanted to have a proper obituary printed in The Washington Post. She’s still planning something to remember her brother in her own way.

“We’re going to do something,” she said. “Even if we just stand on that corner with a blown-up picture of him and sing ‘Kumbaya,’ … ‘We Shall Overcome.’ I don’t care — we’re going to do something.”

More from the series, “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.”

- ‘Everything was on fire’ — remembering the DC riots 50 years later

- DC Uprising: An oral history of the 1968 riots

- Under fire: Retired police, firefighters remember 1968 flashpoints

- ‘The mayor saw it with his own eyes’ — a reporter chronicles 1968 chaos

- After the riots, an activist on trial

- How Ben’s Chili Bowl survived the 1968 riots to become a DC landmark (VIDEO)

- Shattered lives, unanswered questions 50 years after the riots

- Small DC church survived the riots. But then came the wrecking ball. Finally, a rebirth

- Then & Now: Powerful images show 1968 riot damage and rebuilt DC neighborhoods