Ten years after the deadliest crash in Metro’s history, the system is still struggling to bounce back and riders continue to feel the impact every day.

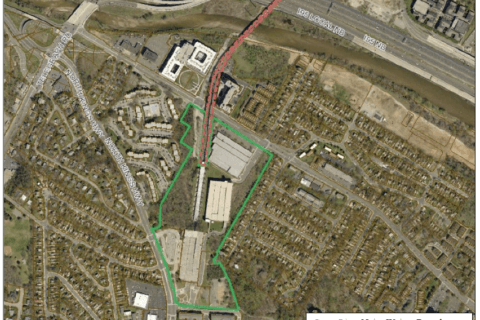

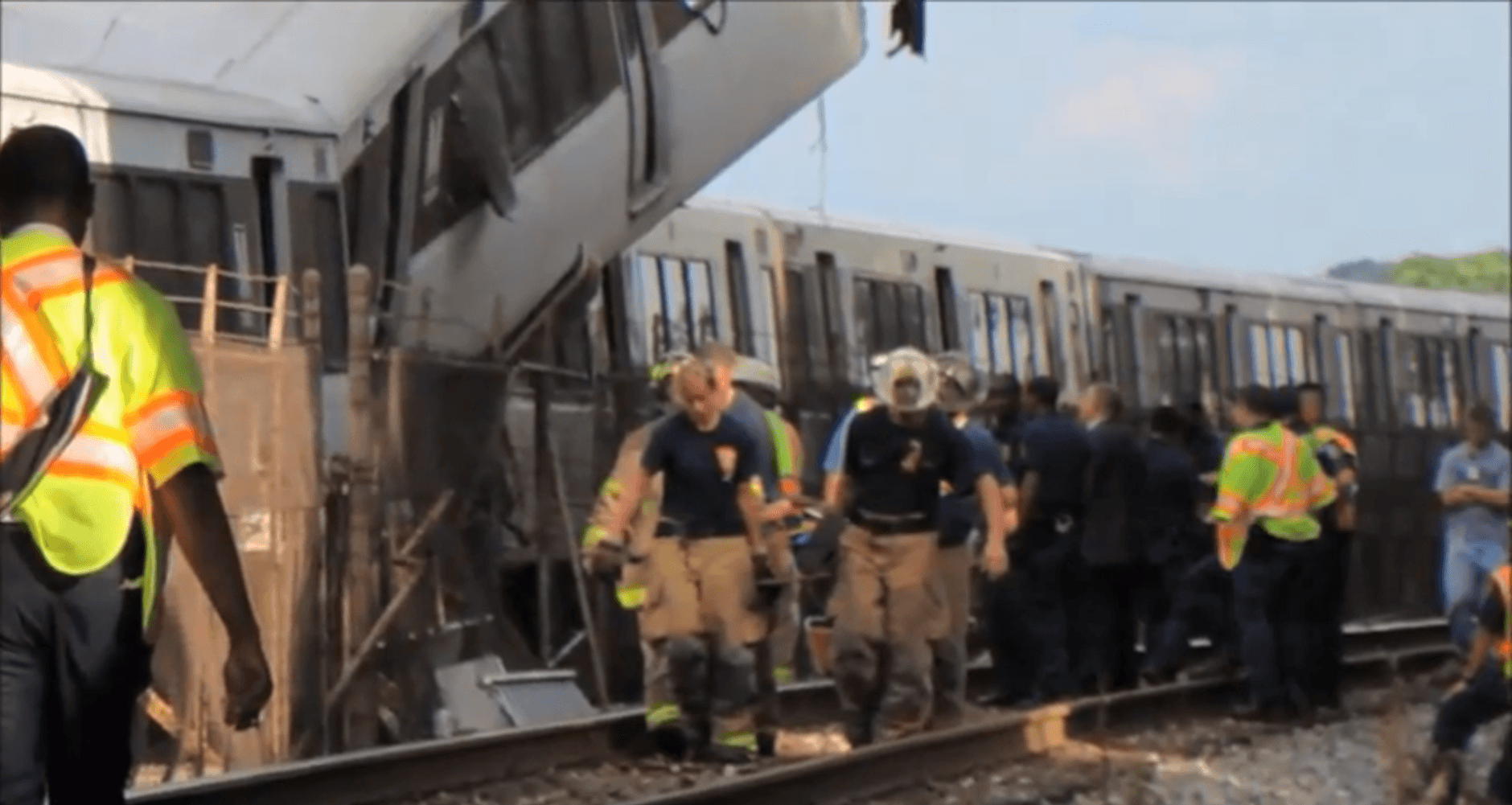

At the height of the evening rush on Jun. 22, 2009, one Red Line train slammed into the back of another that was stopped outside the Fort Totten Station. Nine people were killed and at least 80 were hurt. A memorial is scheduled Saturday.

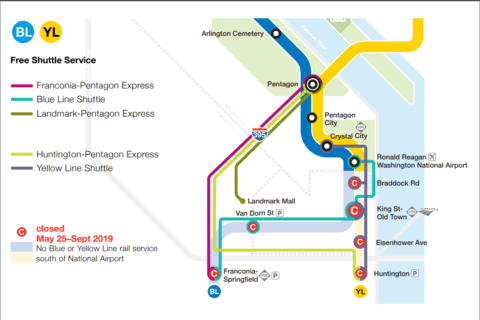

The most obvious changes for riders in the aftermath of the 2009 crash were the expansion of track work shutdowns and the end of smoother automatic train operations.

While Metro has promised a return to automatic operations, there is still no schedule for that to happen, and the agency did not respond to a request for additional information about future plans.

‘Startled:’ First responders remember seeing train in the air

D.C. Fire Battalion Chief Tony Carroll, a lieutenant at the time, was one of the first to arrive at the crash site once dispatchers figured out the crash happened not at the Takoma Station, but instead just under the bridge carrying New Hampshire Avenue Northeast over the Red Line tracks.

“As we were getting to the tracks, you could see kind of people walking up the track. You could definitely tell … they were stunned. They seemed to be kind of not really zombies, but definitely … they were shocked,” Carroll said.

It was only the second time Metro riders had been killed in a crash in the system’s history. The train operator of the moving train was also among those killed.

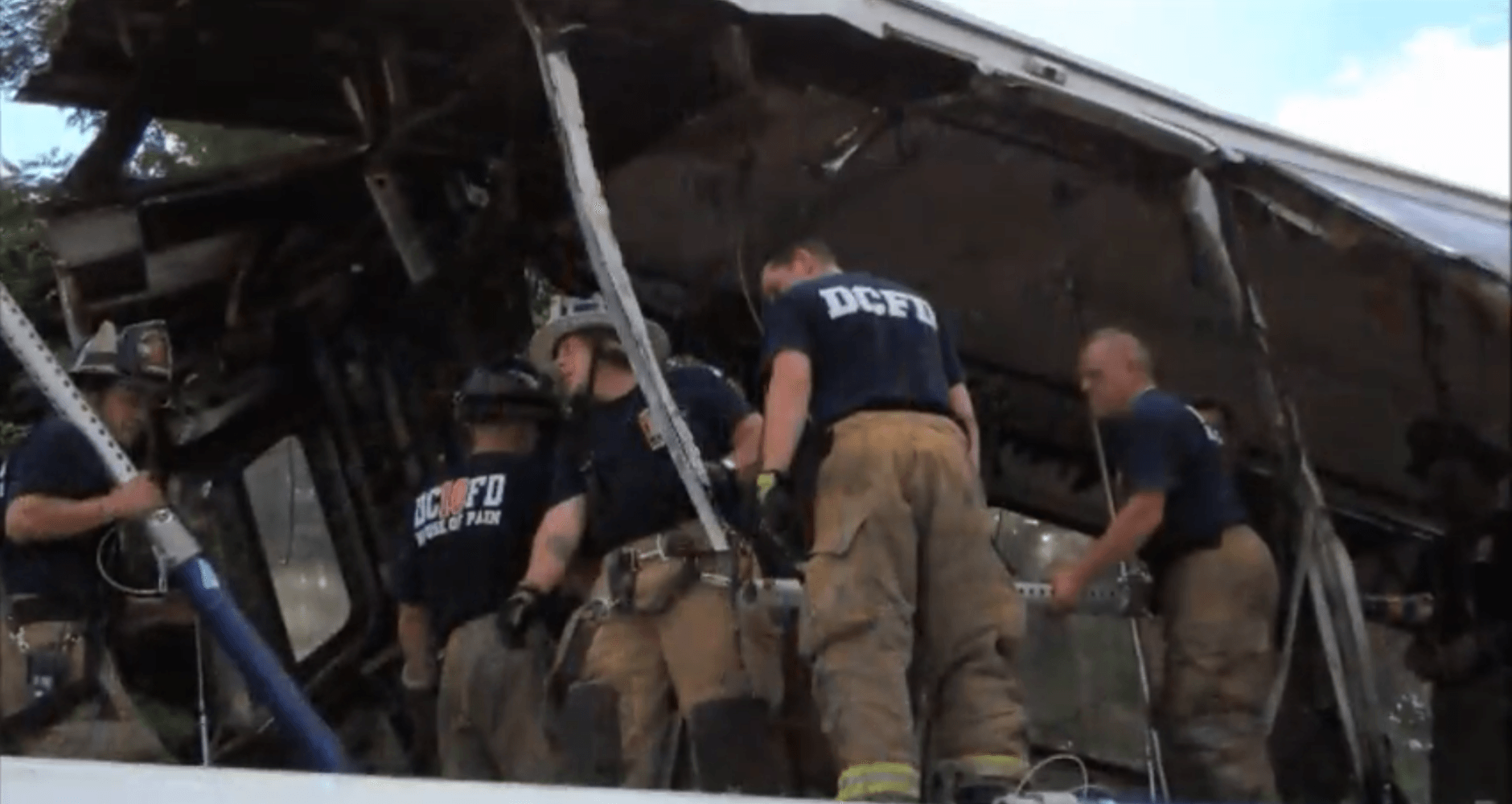

“You could see the end of the train and then the car that was pushed up into the air,” Carroll said. “That really changed it because you knew it was real. We get a lot of calls at Metro that are nothing, and this one, when we got onto the tracks, you could tell something was going on.”

His crew worked their way forward to the front of the train, finding people trapped, shell shocked, seriously injured or dead.

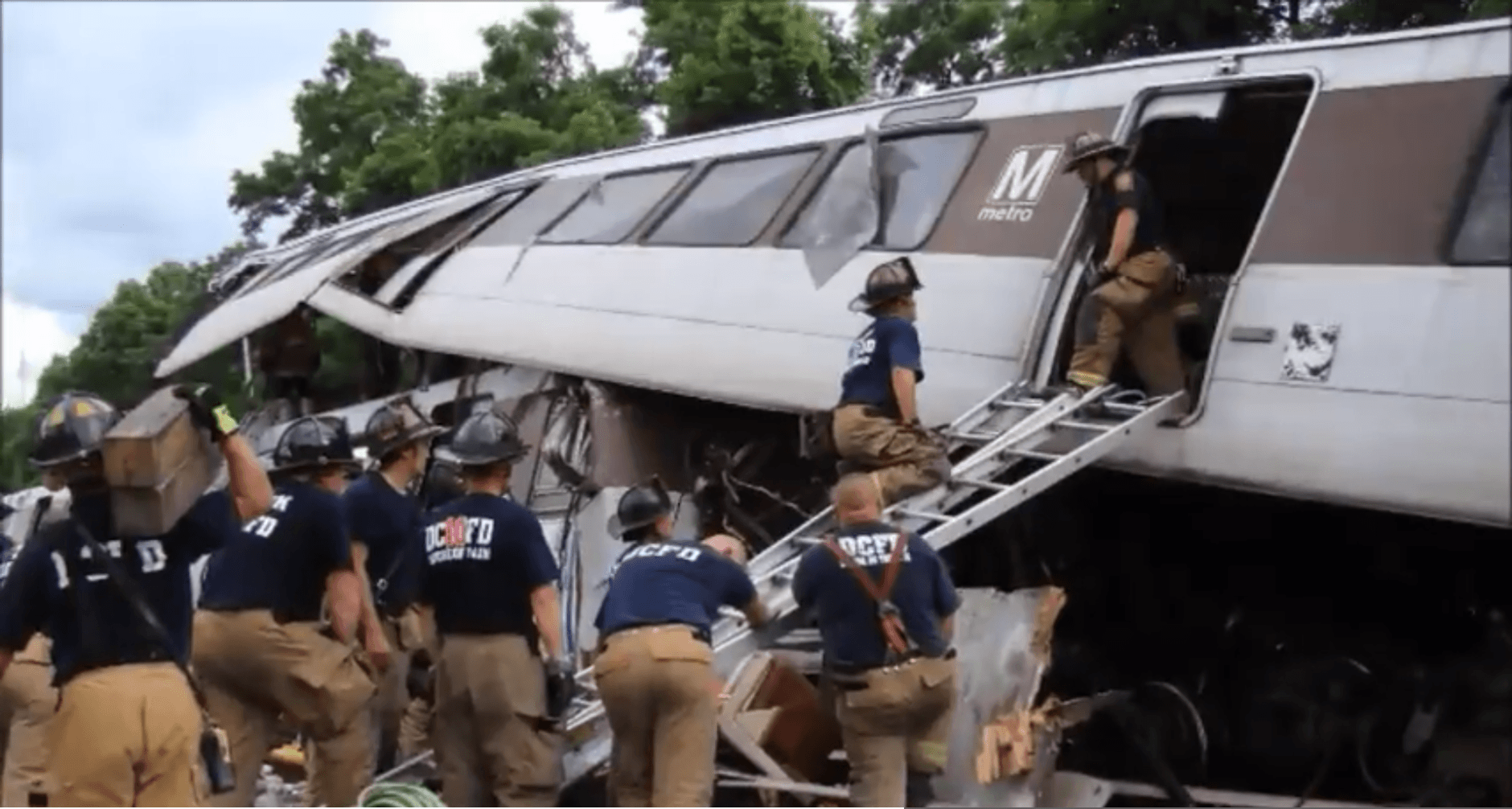

With pieces of the cars tilted or lifted up in the air, it took small hand tools to cut some people free.

“We had to like hold the fuselage of the car above us because it was dangling above,” Carroll said.

A police officer pointed them to a person trapped in the mangled car.

“We looked over at that person and assumed that they were dead, and he said ‘No, listen.’ And she was moaning to us. So we began the operation to extricate that person from the wreckage … there was actually another person underneath of her. Both of them ultimately passed away,” Carroll said.

A volunteer photographer for the fire department at the time, current D.C. Fire and EMS Public Information Officer Vito Maggiolo pulled up as the crews were getting to work.

“I pulled up there, and looked over the fence, and was quite startled by what I saw — the one train car that was telescoped into the other,” Maggiolo said.

He went down onto the tracks.

“I saw one individual being brought down a set of ladders from what appeared to be the roof of the car, and as I was videotaping, I suddenly realized that that was a deceased victim. I stopped the videotaping and they brought him down and covered him up, and a short time later I saw our fire department chaplain coming up onto the scene, and I escorted him over so he could administer last rites,” Maggiolo said.

Recovering the bodies of people trapped in the very front of the train took hours longer.

“That’s tough to come home and then see your family and think that they could have the same incident minding their own business riding the Metro and something like this was to happen, so it emphasizes those times with the family are really, really important,” Carroll said.

Crash reveals failed safety culture

The moving train had been going nearly full speed since circuits had failed to show the stopped train on the tracks ahead.

“One of the trains essentially became invisible to the computer system, and another train was routed into its space,” George Mason University professor Zachary Schrag said.

He wrote the book on the history of Metro called “The Great Society Subway.”

“An accident like this reveals shortcomings in an organization, so those signals which are necessary to run the system safely had not been inspected frequently enough, so the National Transportation Safety Board concluded that there was a problem with Metro’s safety culture that went far deeper,” Schrag said.

While workers have been killed in other incidents, the only passenger deaths tied to crashes or other issues were a January 1982 Orange Line derailment that killed three people on the same day an Air Florida 737 crashed into the Potomac.

“For a generally safe system, it’s pretty shocking when passengers are killed,” Schrag said.

Among the numerous recommendations from the National Transportation Safety Board, Metro has since taken all of its original railcars out of service.

While the 2009 crash clearly highlighted Metro’s aging infrastructure, it did not mean change was easy.

“The subsequent fatality in 2015 suggested that not enough had been done to improve Metro’s safety culture, and probably the worst indicator of this was the fact that management decided to shut all trains down for a day in 2016 for a full on safety inspection of some of the equipment, so we can’t say that the accident reversed the longstanding problem of the lack of safety culture in the organization,” Schrag said.

Since Carol Glover’s death near L’Enfant Plaza in 2015, Metro has begun more extensive track work shutdowns and single-tracking, cut back hours, and promised increased inspections and maintenance work.

“It’s very hard to turn around many years and even decades of neglect,” Schrag said.

Metro’s long-term plans include projects totaling billions of dollars.

“The same issues that the collision exposed in terms of the failure to inspect aging equipment, and the need to possibly shut down lines for longer periods of time in order to inspect and maintain that equipment — that does affect reliability and that affect’s people’s ability to get where they’re going predictably and on time in a reasonable amount of time,” Schrag said.

Ridership has been falling over the last decade, including a significant decline since the 2015 smoke incident and Metro’s extensive 24/7 work zones.

“Certainly the reduced level of service is going to affect people’s decision to ride or not to ride,” Schrag said.

Other factors are involved too, though to lesser degrees, such as ridehailing companies. Uber started in California in 2009.

“For most people deciding how am I going to make a trip today, that issue of reliability is probably more important than the very limited risk of injury,” Schrag said.

Designed for automatic

Metro had been designed ahead of its 1976 opening to run largely automatically.

While a train operator in manual mode relies on the same signals, automatic operations were suspended following the 2009 crash and have not returned.

Metro had announced a return to automatic operations in 2015, but that was quickly and quietly scrapped. Manual operations are less efficient and less smooth for riders than the automatic system.

“The thought of the engineers in the 1960s and 1970s was that machines were more reliable than human operators, and that’s a debate that is still unsettled 50 years later,” Schrag said.

The questions apply in flight, driving and other modes of transportation, too.

“There’s a kind of long-standing issue here of whom to trust more: the faulty human or the faulty computer, and both of them are imperfect,” Schrag said.

Metro does plan to return door operations to automatic mode in a few weeks on the Red Line, which will shave time off trips, but that relies on technology that confirms the train is stopped in the station, not the technology that handles trains in motion.

Shiny and new, to old and crumbling

Metro was small, shiny and new when it opened in 1976.

Despite glitches such as one train that operated without an operator, the first major questions about the reliance on automation most of the time came around after 1982 crash.

Some experts started to raise questions about Metro maintenance practices and plans in the following years, but public perception remained good.

“Metro retained a sense of being in pretty good repair, on the surface I would say, into the 1990s,” Schrag said. “It wasn’t until the late 90s, 1999 or so, that the aging of Metro became more visible, and I think the 2009 collision accelerated that perception,” he said.

The Fort Totten crash also highlighted longstanding organizational problems going back to 1970s, including a lack of expertise.

“It’s hard to know how to turn around a culture,” Schrag said.

Still riding?

Maggiolo and Carroll did pause after the crash, but did not change their use of Metro.

“It did give me pause in terms of the revelations that came forth about the lack of safety on behalf of Metro at that time, but I’ve been to transportation accidents before, and we learn. Every event of this magnitude is a learning process,” Maggiolo said.

Carroll saw the carnage where the trains collided, and considered riding in the middle of trains rather than the front or rear.

“I consider it to be a pretty safe operation, so I wouldn’t hesitate to ride Metro,” Carroll said.

Still, the crash highlighted the importance of being prepared, Carroll said. He now helps train others in the fire department.

“Even if you think it can’t happen, it can, so you have to be ready,” he said.