A half-century ago Friday, the break-in at the Democratic National Committee offices at the Watergate complex in D.C.’s Foggy Bottom led to an investigation that gripped the country for two years and led to the U.S.’ only presidential resignation. This week, WTOP’s Rick Massimo is talking with experts about how the entire affair has affected American politics, history and even the language ever since.

When the Watergate scandal broke in 1972, WTOP Emeritus Senior Congressional Correspondent Dave McConnell was already reporting on Capitol Hill. Meanwhile, Capitol Hill Correspondent Mitchell Miller was still a kid. For McConnell, the break-in and the investigation that followed constituted a story that wouldn’t stop growing; for Miller, it was the lead-in to a career in journalism. They both spoke with WTOP about their memories of Watergate — and they couldn’t resist drawing parallels to the present day.

McConnell remembered covering the break-in as a local crime story at first — “It involved something going on with some operative of the Nixon campaign,” he remembered. “And we knew that much, but we weren’t paying that much attention.”

- ‘Criminal mindset’ — author Garrett Graff on his new history of Watergate

- ‘Still grappling with it’ — 50 years of Watergate on film

- ‘Embracing its history’: Watergate Hotel trades on its claim to fame

- PHOTOS: Watergate in pictures

- More Watergate Stories

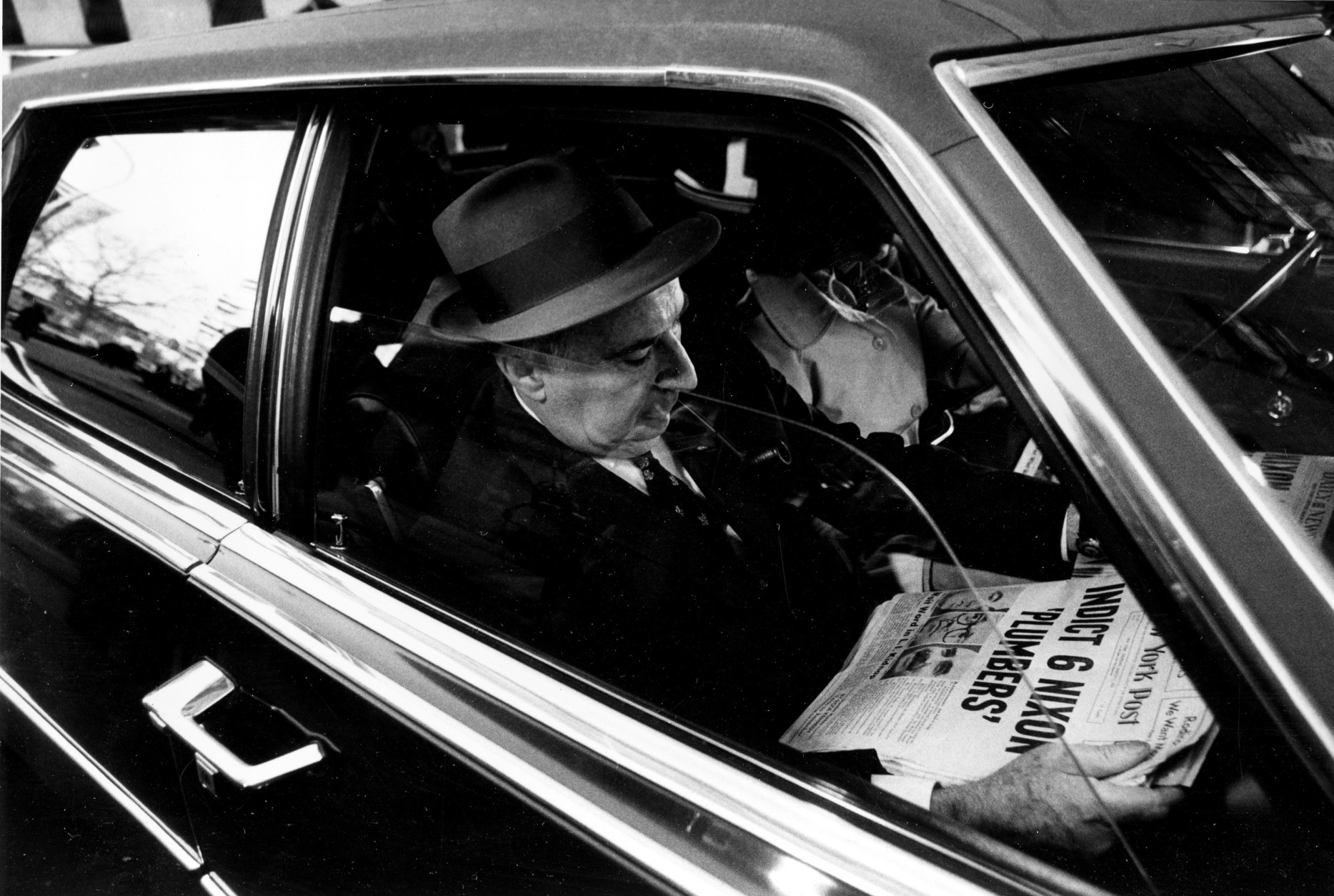

The idea that the Watergate break-in — it was the second one, McConnell recalled; the goal was to replace malfunctioning listening devices that had been installed during an earlier break-in that wasn’t detected — would be the thread that would eventually unravel the Nixon presidency seemed unlikely.

“The idea that there might be some kind of a plot that Richard Nixon — the president — was overseeing didn’t seem likely to me,” McConnell said — “although we did know this was ‘Tricky Dick’; he had been known in the past to do some nefarious things. But at the same time, it just didn’t seem to fit.”

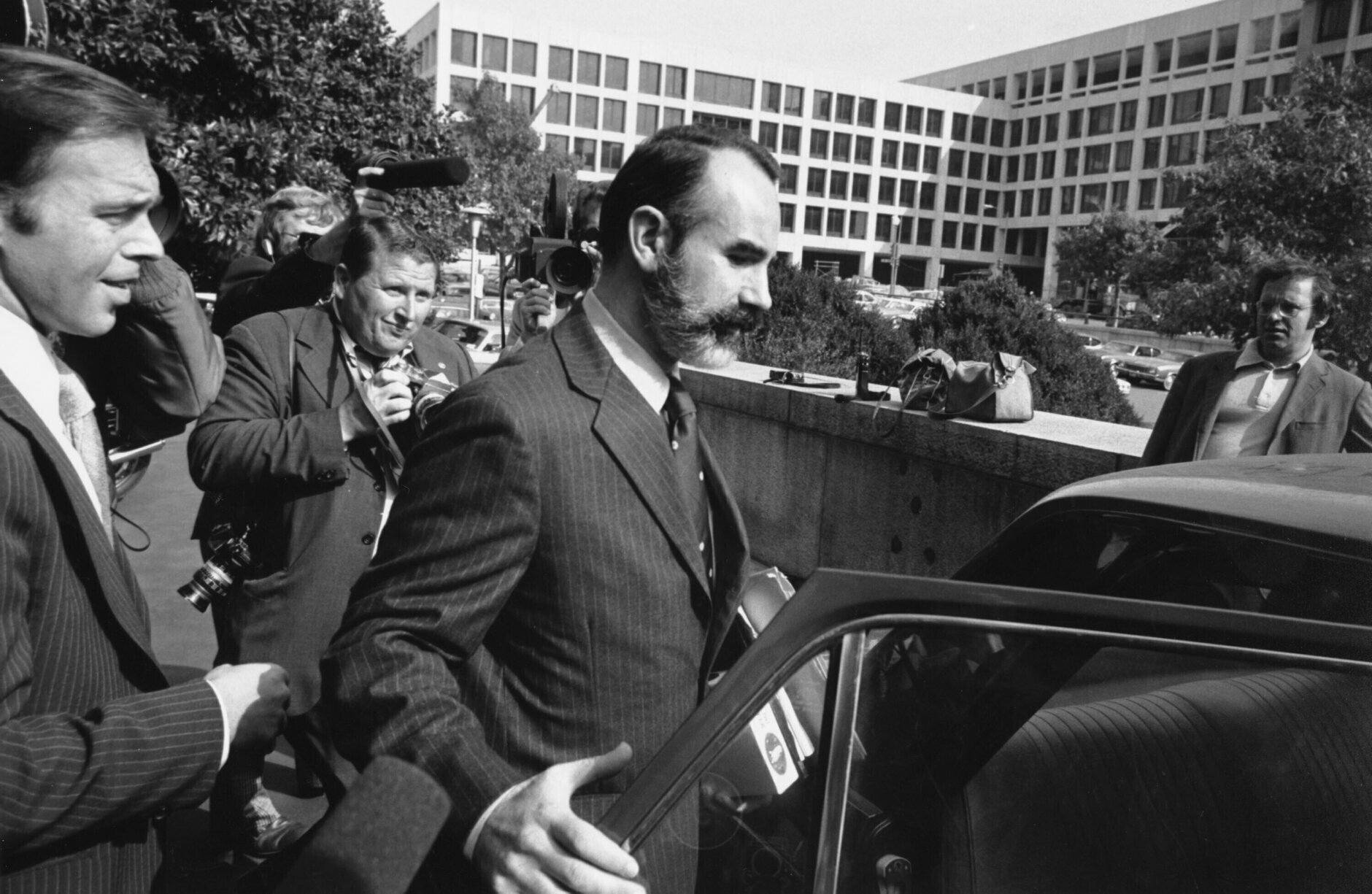

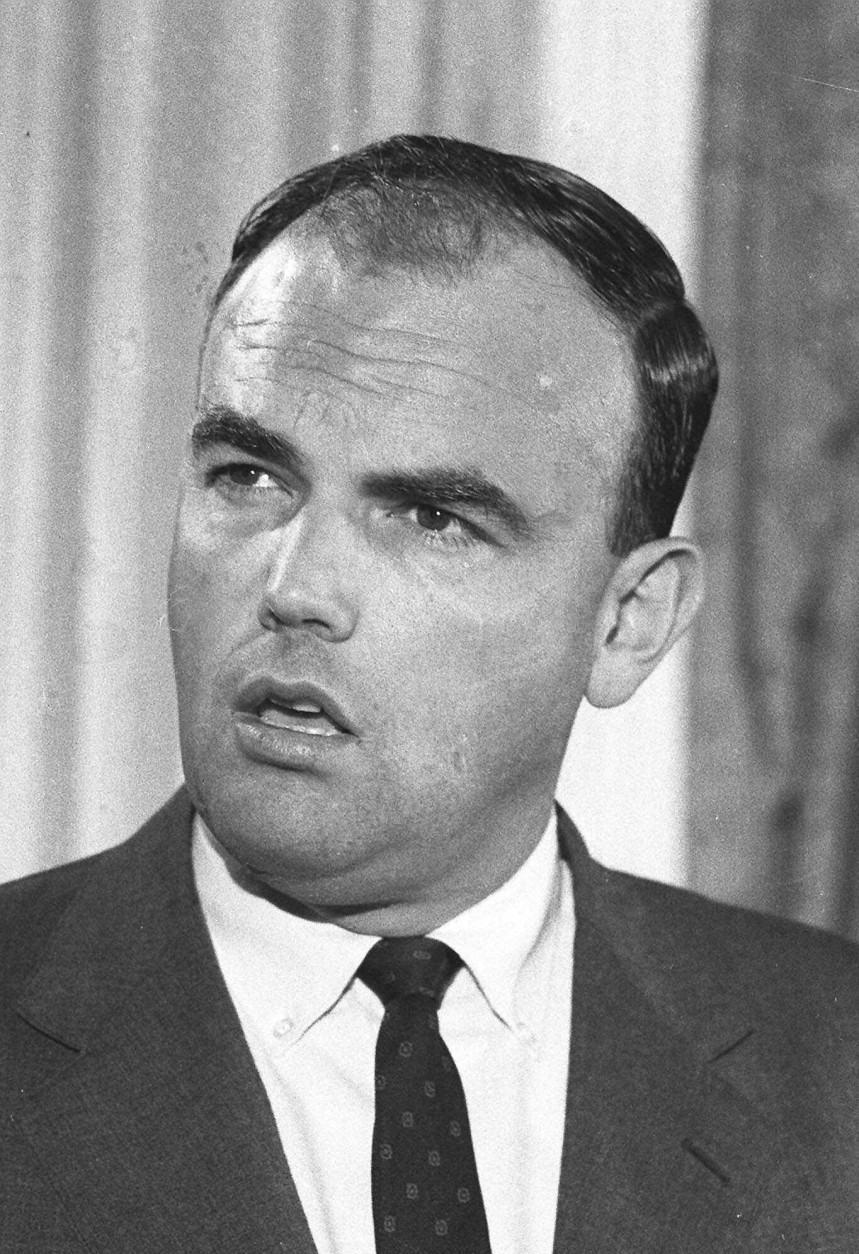

Miller pointed out that the term “Watergate” refers to an entire campaign of dirty tricks, break-ins and cover-ups, and that the “White House Plumbers” — the secret parallel security operation that carried out the Watergate break-in — was behind a lot of crimes and shenanigans, beginning with attempted revenge for the leak of the Pentagon Papers.

And the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate was the continuation of a campaign that essentially promoted Sen. George McGovern as the preferred candidate to take on Nixon that fall.

“They were really trying to get McGovern as the candidate to run against Nixon,” Miller said, “because they thought he was the weakest. And at one point, Ed Muskie, the senator from Maine, was considered the strongest candidate, and they had all kinds of sabotaging efforts to undermine his candidacy, including planting of false information that he had somehow said bad things about French Canadians who lived in New Hampshire.”

That was one of the things that threw McConnell when the Watergate scandal began: “It led me to believe early on when I was covering this, ‘What’s the worry about McGovern? He doesn’t have a chance.’”

Nixon won a huge victory — 49 states in the 1972 election — but the investigation and the revelations didn’t go away. The summer of 1973 was dominated by the Watergate hearings in the house and Senate.

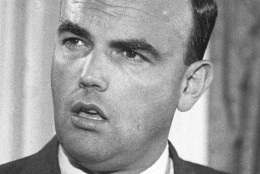

McConnell remembered the leaders on the Senate committee: Sen. Sam Ervin, a Democrat, was the chair — “a feisty, Central Casting Southern character who went to Harvard and had a mind like a steel trap,” and Sen. Howard Baker, “a rising star in the Republican Party, who will go down in history as the man who coined the phrase ‘What did the president know, and when did he know it?’”

McConnell said the revelations were as gripping to him as they were to the rest of the nation. “At this point in time,” he said, “everything was amazing.”

‘You knew deep in your gut that this was wrong’

Miller said the hearings — about 50 meetings, all televised — were part of his summer, just like everyone’s, and he was soaking up the information.

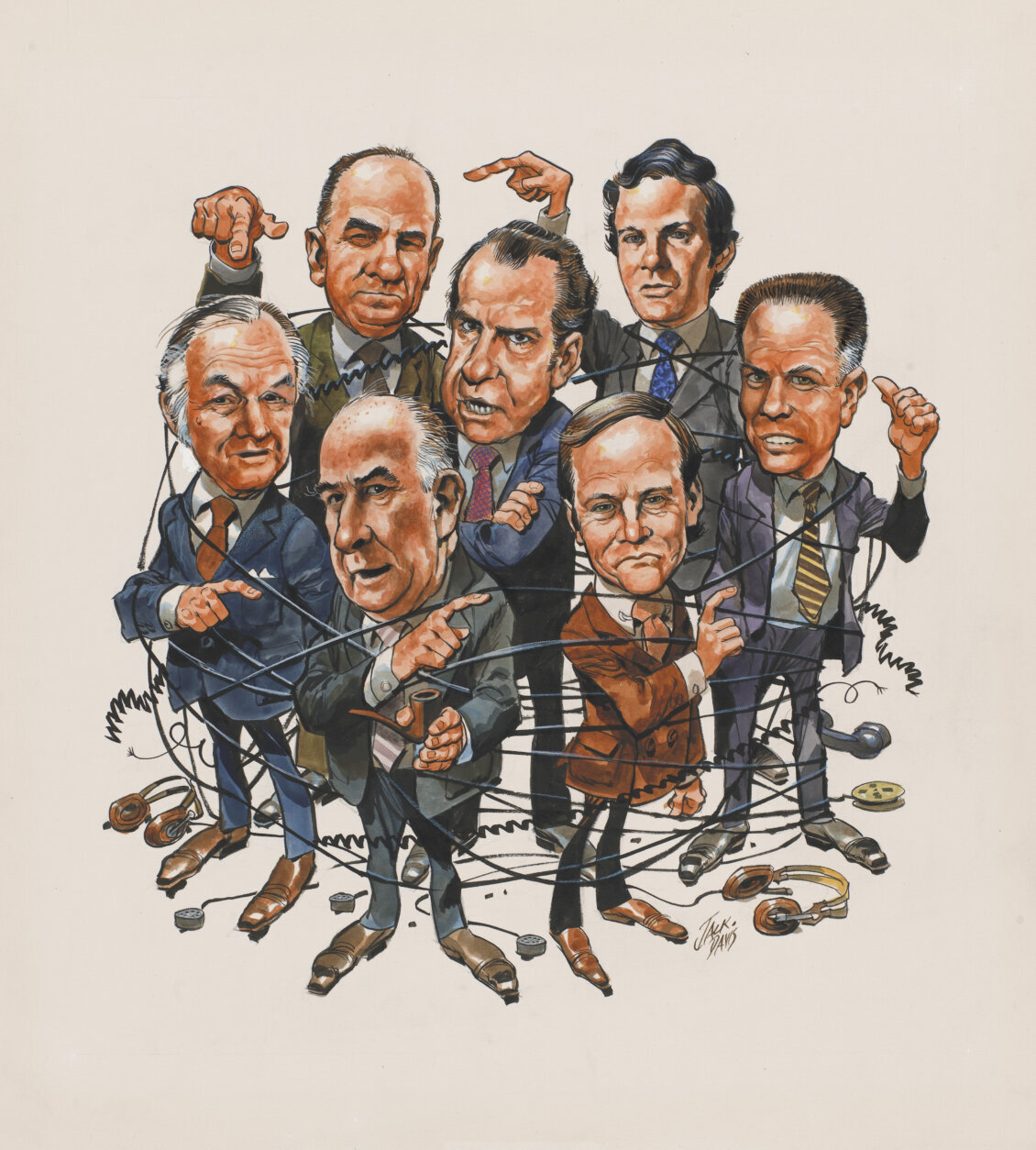

“Up to that point I had, like a lot of kids, read the sports section and kept-up with sports biographies. Watergate was really my introduction to politics in the United States. And what an introduction it was, right? John Mitchell, G. Gordon Liddy, James McCord, E. Howard Hunt — they were almost like mythical, fictional characters to me at some point.”

He added, “At the time, of course, I didn’t fully understand how complex this was. But at the same time, you knew deep in your gut that this was wrong.”

While the hearings went on, however, Congress kept going, McConnell said. “In the sense of a workmanlike, accomplishment situation, you had bills being passed; you had hearings, you had other things going on the Hill. … They were out to get each other on floor votes, on legislation. But they all felt at some point, ‘We’ve got to hammer out a compromise on a particular bill or a particular issue.’”

He was listening to the hearings on WTOP the day in Oct. 1973 when White House aide Alexander Butterfield acknowledged, in response to a question from Republican Sen. Fred Thompson, that there were indeed listening devices in the Oval Office — that so many of the conversations that the committee and the nation had speculated on and argued about had in fact been recorded.

That, McConnell said, was the turning point: “That was when the world ended — when we knew that they had records of what people had been saying. We knew the jig was up.”

The jig was in fact up — after a lengthy battle to keep the tapes secret, and to provide only edited transcripts, the tapes were released, and on Aug. 9, 1974, Nixon resigned.

“Richard Nixon harbored conspiratorial thoughts all of his political life,” McConnell said. “And he really was insecure, which was amazing, because some of the foreign policy things he did, some of the domestic things he did, were truly the work of a very active and accomplished political person. But he still had this doubt.”

Nixon resigned the day after a group of Republican senators led by Barry Goldwater, one of the godfathers of the conservative movement, visited him at the White House and told him the impeachment resolution, which would throw him out of office, would pass — with plenty of Republican support.

Baker, McConnell said, had been seen by some as someone who would back Nixon no matter what. It didn’t turn out like that.

“Baker started out skeptical of the hearings,” McConnell said. “But then he came very quickly to realize something really serious had happened. And he wasn’t Howard Baker, Republican; he was Howard Baker, senator. And the same thing with Sam Ervin. He didn’t look at it as a Democratic victory; he looked at [Watergate] as an assault on the government.”

Not everyone did, McConnell said; plenty of people “out there in the hinterlands still thought Richard Nixon had been tried unfairly, and it’s amazing.”

Past and present

“The feeling that I had was that this was the biggest story I’ll ever cover,” McConnell said. “Little did I know what would be happening after that.”

Neither McConnell or Miller were asked to compare the Watergate saga, and the hearings, to the Jan. 6 hearings, but they both did anyway.

“The Senate voted 77 to 0 to create the Watergate Investigative Committee,” Miller said. “Contrast that to today, where it was all that the Congress could do to come up the House Select Committee on Jan. 6. The times are so much different now in terms of bipartisanship.”

The Watergate committees had “clear-cut evidence of wrongdoing,” McConnell said, and when people saw that evidence, “they agreed with it.

Now, you have a panel, the Jan. 6 panel, doing much the same thing. And many people would say they have got a very solid case, relative to what President Trump did and what his minions did. And yet, there’s no guarantee, there’s no evidence so far that a lot of people are really changing their opinion of Donald Trump, whereas opinions did change on Richard Nixon.”

McConnell also pointed out that scandals such as Watergate began the numbing process for a lot of people to dubious Washington behavior going forward. “The shock value was very high then; it’s not so high now. You have an awful lot of competition for this kind of a scandal.”

Miller added that Watergate was an operation with plenty of subterfuge.

“You found out that there were all these things going on behind the scenes with the government that people probably didn’t really realize could even happen. And that was part of that surprise factor. Today, many of the things that former President Trump is accused of, basically, happened in plain sight.”

If somebody at the time of Watergate had said something like Jan. 6 would happen 50 years later, “people probably wouldn’t even have believed it,” Miller said. “And yet, here we are today. And there’s a sizable percentage of the population that says ‘Well, it wasn’t really that bad. It could have been worse. Get over it; start looking at other issues.’”

Trust

McConnell said it’s hard to imagine the kind of trust the government was held in when the Watergate scandal broke. Lot of people believed Nixon’s protestations of innocence because they simply couldn’t believe that the president of the United States would lie to the nation, would openly order the stonewalling of a criminal investigation. (As more Nixon White House tapes have been released over the years, it’s turned out he was implicated of arguably worse than that.)

“The Watergate saga did a lot to disabuse people of the notion that the government always acts in their interest,” McConnell said, adding that the concurrent Vietnam War controversy was another contributing factor.

“Since those times, varying issues, varying spectacles, varying episodes have come up to further erode public trust of the government,” McConnell said. “But many people think it all started with Watergate.”

For someone exposed to Watergate at Miller’s age, though, that trust was never formed in the first place. “All of those things just said to young people, well, maybe things shouldn’t be trusted.”

For Miller, it was part of the motivation to go into journalism.

“I already knew that I was going to go into journalism when I was in high school,” Miller said, calling the era “kind of the golden years. … It brought about a whole generation of journalists who really got into the business, I think, for the right reasons.”

While there’s “a lot of showbiz to broadcast journalism,” Miller said, the Watergate saga had a deep impact on journalists, future journalists and the public: “That you could actually initiate change or reform by showing that things were going the wrong way.”

“That was what really caused us to become interested in the workings or the lack of working in government. And it really has an impact to this day.”