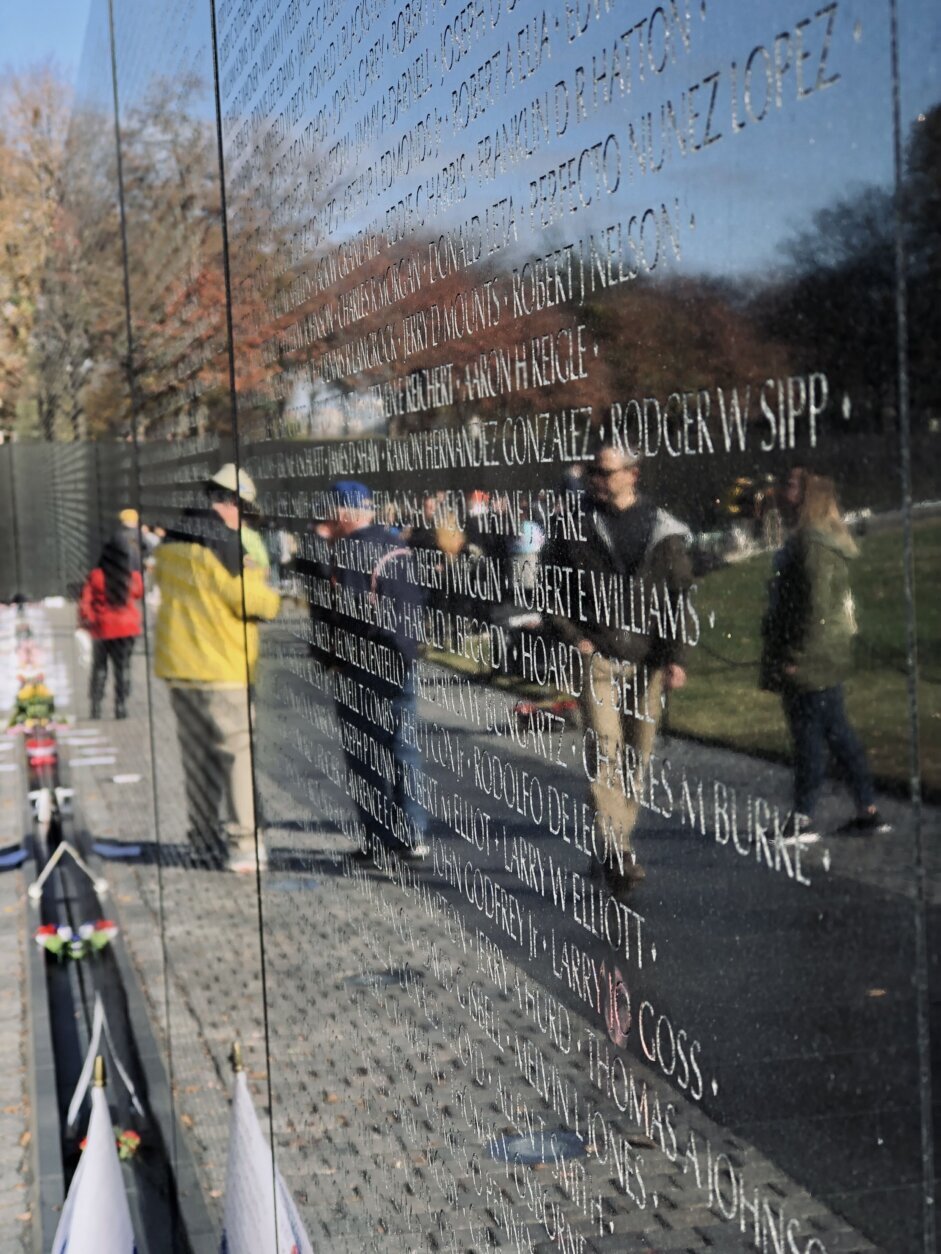

Forty years after the Vietnam Veterans Memorial first opened to the public, millions still flock to the spot on D.C.’s National Mall.

Some are there to search for the names of their loved ones, while others leave tokens or letters. Thousands of students, having studied the war in class, come to connect with a slice of history they’ve only read about in books.

But when it was first unveiled to the public, the memorial was criticized as ugly and unpatriotic. Some even derided it as an insult to those who served.

Robert Doubek, who served in Vietnam and is one of the founders of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, said it may be hard for those who don’t know the history to realize just how much controversy surrounded the project.

“I think it was normal for a lot of people to assume there would be some sort of big statue or a big building, which is the way traditional war memorials were,” he said.

- Volunteers call the Vietnam Veterans Memorial’s power to connect people ‘magical’

- Veterans Day: What’s open, what’s closed

- Veterans Day: Freebies and other specials

- More Local News

But there were a number of considerations that went into the memorial’s planning.

It was intended to honor all of those who served, not just those who died in the war — and it couldn’t have a political slant.

“From the beginning, we set a theme that this memorial should be reflective and contemplative in nature,” Doubek told WTOP. “What we came up with was a place, rather than an object … a place where people could come to remember, to think, to heal.”

This video is no longer available.

Nowadays, people visit and have rubbings of names made, placing paper against the smooth, black granite, and rubbing a pencil over the paper, to get the outline of the name that’s been etched into the surface.

Some leave photos, cards and letters to the dead. One recent letter left at the base of one panel included the message, “My dad, my hero, my guardian angel. You are always with me in my heart and in my thoughts. You make the stars shine bright.”

It was signed, “Forever your little girl, Kimberlee.”

Doubek said that while it was important to have a memorial to honor the veterans who served, he was, in fact, ambivalent about the design of the memorial at first.

But with time, he said, “I’ve concluded this really does honor all who served.”

He continued: “When I see people leaving mementos at the wall, it indicates that the role of remembrance is still a very strong element generated by this memorial.”

On a visit the day before Nov. 11, Doubek walked along the path at the memorial, stopping to shake hands with volunteers who help visitors find names on the panels, and share stories about the wall.

He said volunteers are keen observers of interactions at the memorial, and he referred to what they called “wall magic.”

One of Doubek’s favorite stories is the account of two veterans who bumped into each other on the day the memorial opened. They had served together.

“And it turned out they were looking for each other’s name,” said Doubek. “They both had, for all those years, believed the other had died. They found they both had made it.”

Standing back from the memorial, Doubek said, “I’m proud of my role in creating what’s become an American icon, but I’m humbled by the pain and sacrifice it represents.”

Doubek added, “The country owes a debt of gratitude to people who put themselves in harm’s way on behalf of their country and especially those who did not return.”