Governors in Texas, Florida and Arizona have been shipping migrants who show up in their states to cities and towns, including D.C., for most of this year. More than 9,000 people have been dropped in the District, officials say, and the scheme got more visibility earlier this month, when two busloads of migrants were dropped off at Vice President Kamala Harris’ residence.

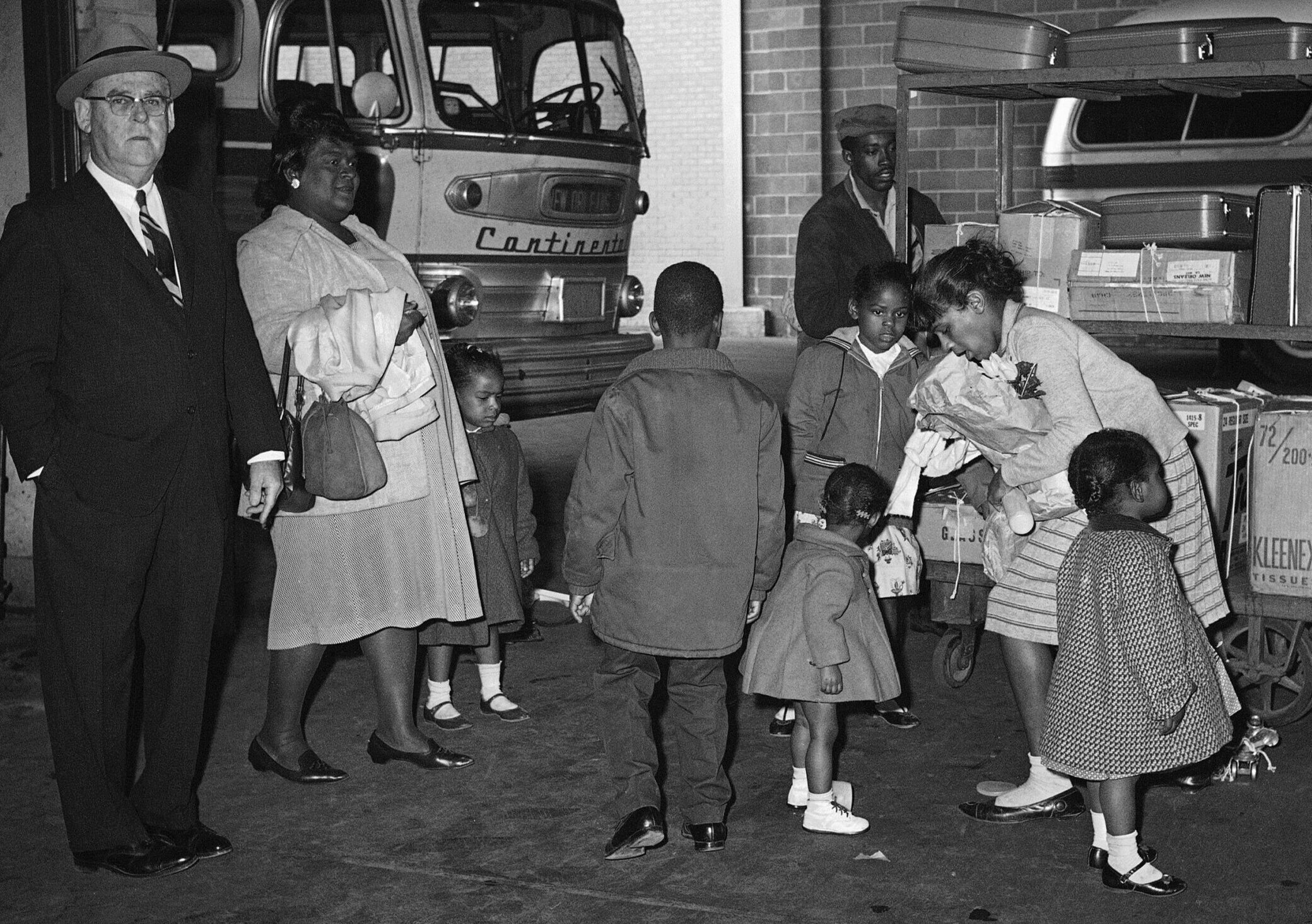

But when two planeloads of migrants were dropped in Martha’s Vineyard, it sounded familiar to a few historians, including those at the JFK Presidential Library. They pointed out the similarities to the so-called Reverse Freedom Rides, which saw Black people bused from the South to places such as Hyannis, Massachusetts, where the Kennedy family compound was.

The chief historian of that ’60s episode said he sees parallels with today’s situation.

Clive Webb, professor of modern American history at the University of Sussex, said the intent of the Reverse Freedom Rides was basically similar to that behind the present-day busing and flying of migrants to “blue” areas of the country.

Segregationists organized the bus rides “as a way of saying, ‘If you really care about the well-being of African Americans, and all citizens, then you will be a welcoming host for these people.’”

The Civil Rights-era rides were the brainchild of segregationist George Singelmann, the head of the New Orleans Citizens Council, formerly known as the White Citizens Council. The name was formulated as a response to the Freedom Rides, in which northerners headed to the South to help Black people exercise their voting rights.

Singelmann played coy in contemporaneous news reports, pointing out that Black people signed up for the rides themselves, saying the news media, the NAACP and others had “constantly maligned and chastised us” for “our treatment” of Black people. “For such people who are not satisfied and felt oppressed,” he said, “we thought we would afford an opportunity to go to a Northern area where conditions are supposedly better.”

The Citizens Councils thought the arrival of Black people in the District “would be a cause of great embarrassment to officials, because it would expose the limitations of their own support of African American rights,” Webb said.

D.C. was specifically targeted because of its status as the nation’s capital. The home-state residences of pro-integration members of Congress were also popular destinations. Singelmann at one point called Minnesota Sen. Hubert Humphrey “a door prize.”

“Dumping indigent African Americans at the holiday home to the Kennedy family was one thing, but bringing them to Washington, D.C., was a calculated move to put them at, not quite literally, at the doorstep of the White House,” Webb said.

Failure

It’s hard to know how many people were bused to the North, in part because Singelmann often announced plans to transfer a large number of people that would then fall through. A plan to send two buses with nearly 80 Black people aboard to D.C. was called off; in the end, Webb said, the number bused to D.C. was in the “dozens, not hundreds.”

Those who did arrive in the District, Webb said, were welcomed. Newspaper accounts of the period said a Citizens Committee for New Orleans Refugees was established in D.C. to help new arrivals with immediate needs. “Temporary accommodation was found, and immediate material support,” Webb said.

After that, it gets difficult to track what happened to the riders. A general warning had been sent south that D.C. was a tough place to make a living, and that you had to live in the District for a year before you were eligible for public assistance — both of which contradicted the sales pitch given to the riders by Singelmann’s crew.

Webb said that while the Reverse Freedom Rides seemed like an aggressive move at the time, they arose out of weakness — and were a failure.

He wrote in his article that while Singelmann and the Citizens Council said the rides were supposed to embarrass Northern liberals, the real goal was twofold: to solidify the segregationists’ political base and to reduce the political pressure they were facing. Supposedly, “the federal government would not be in a position to keep practicing hard for civil rights reform,” Webb said, but that’s not what happened.

“It’s a wild calculation on the part of the Citizens Council in the ‘60s, driven by increasing desperation, because the tide has very much turned in terms of the Civil Rights struggle,” he added.

Even then, Webb said, the ploy didn’t work: “They not only failed to kind of expose more liberal Northern politicians in the way that the Citizens Council anticipated, but they actually put a lot of adverse publicity for the Citizens Councils.”

No historical parallel is perfect, Webb said, and one difference in today’s situation is the power of the state: The Reverse Freedom Rides were sponsored and organized by private citizens, while today’s busloads and planeloads of migrants are arranged by governors.

“This is a demonstration of the inequalities of power, fundamentally, isn’t it? If you can use the apparatus of the state as a means to enforce your dominion over others. That does tell us something about who holds the apparatus of power in American society, then and now,” Webb said.

‘An inhumane act’

Webb added that this all rhymes, historically, with the move to send migrants to D.C., Cape Cod and other Democratic-controlled areas of the country.

“The parallel is that I think it’s an inhumane act,” Webb said, “in which the welfare and well-being of people who there’s an attempt to relocate, is not the concern here.”

“Historical parallels are never precise,” Webb said. “And obviously, there’s a different context here in this story with contemporary immigrants. But it’s coming out of the same political playbook, I think, with similar motivations — it’s not an attempt to engage seriously, with the issue of immigration. … I think it’s not an attempt to do anything substantial or serious; it’s an attempt to highlight an issue.”

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, for his part, has taken different stances on the issue depending on whom he’s speaking with. A spokesperson for the governor told The Associated Press last week that “Florida gave [migrants] an opportunity to seek greener pastures in a sanctuary jurisdiction that offered greater resources for them, as we expected,” while DeSantis told a conservative gathering “They don’t like when the red states are sending illegal aliens to their communities.”

However, many, if not most, of the migrants sent north are political asylum-seekers and not here illegally.

Webb said the governors of states sending migrants north aren’t in great historical company.

“I don’t know to what extent the people behind the current story were at all aware of, or interested in emulating, what happened 60 years ago,” Webb said; “that strikes me as fanciful. But it does suggest at the same time that you need to be aware of the lessons of history.”