This story is part of the WTOP series, “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.” Each day this week, we’ll tell the stories of the upheaval and tumult 50 years ago through the eyes of those who experienced it.

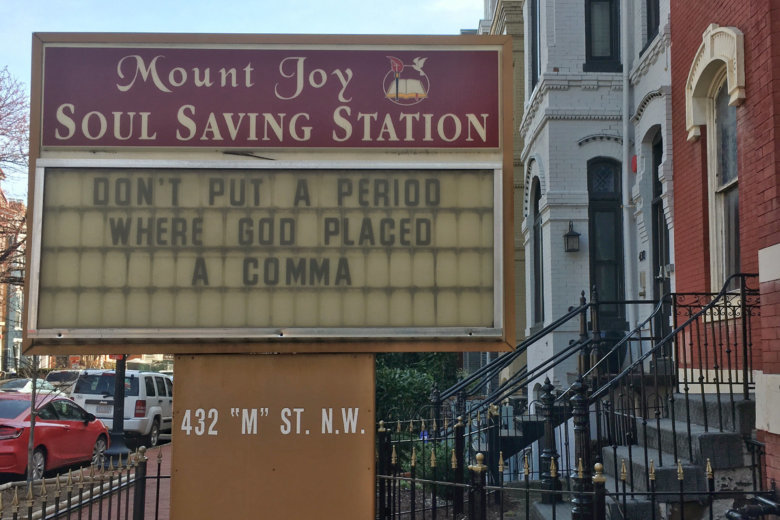

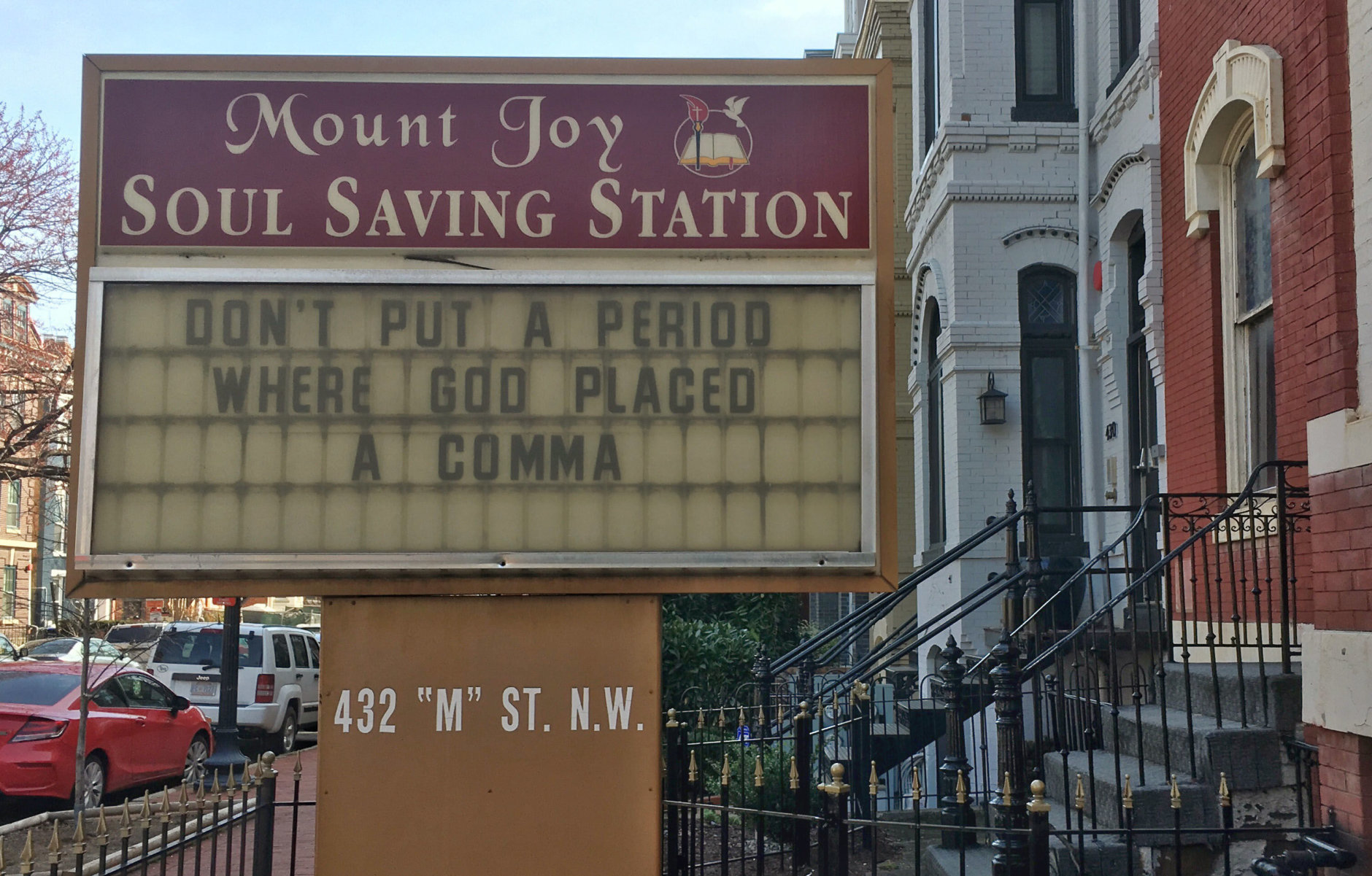

WASHINGTON — In 1968, Mount Joy Soul Saving Station, a small Pentecostal church, sat sandwiched between two storefronts near the corner of Seventh and T streets in Northwest D.C.

The church, led by Pastor Hattie Bynum, sat in the heart of the Shaw neighborhood that would be ravaged by fires and looting in the wake of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

But Mount Joy survived with only a broken front window. Inside, chairs were still neatly arranged for Sunday service and the Bible lay untouched on the pulpit.

A few years later, the D.C. government accomplished what all of the tumult during the 1968 riots couldn’t. As the “urban renewal” push swept D.C. neighborhoods after the riots, the church mistakenly wound up on a list of properties to be demolished — and the wrecking ball came for Mount Joy.

But the church’s story was far from over.

How Mount Joy survived the riots, urban renewal, gentrification and all the other changes half a century has wrought on the landscape of the city is a testament to Bynum’s faith, resilience and what her congregation calls her supreme “stickability.”

“Nothing is hopeless,” Bynum, now 94 and only recently retired from full-time ministering duties, told WTOP in an interview for the weeklong series “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.” “As long as we had life, we were not hopeless.”

Ground Zero: The blocks around Mount Joy

Bynum was working when news broke of King’s killing in April 1968 — not behind the pulpit, but at her day job as a nurse at George Washington University.

In the days that followed, as unrest spiraled out of control throughout the city, the hospital locked the doors and Bynum was unable to get home, she recalled. She worried about her son and daughter both due home from school. Would they get caught up in any of the disorder erupting on the streets?

“But one of the members of the church thought about my children and she came over to my house and stayed with them,” Bynum recalled.

Over the past dozen years — starting out as a street-corner preacher and then through a series of small storefront churches — Bynum had built a small but sturdy congregation of devoted followers who looked out for each other like family.

Since 1965, the church had conducted services out of the Seventh Street storefront, an old record store. The congregation included dozens of neighborhood children. Many of them poor and neglected, Bynum said; nearly all on government assistance.

When the riots erupted, Sevennth Street was among the hardest-hit areas in D.C. In terms of the sheer number of buildings wrecked, the blocks surrounding tiny Mount Joy were Ground Zero.

After the smoke had cleared, the neighborhood looked like a war zone.

But several days later, when she went to check on the church, Bynum discovered Mount Joy had survived.

“We had a cracked glass, that’s all … The fire didn’t even touch the church,” she said. “It burned out the building next to it, and it burned out the building on the other side of it. But nothing, not even the smoke, was in the building. You couldn’t even smell the smoke.”

In the aftermath of the uprising, though, much of the neighborhood lay in ruins.

Hundreds of families living in ground-floor stores were burned out of their homes. Bynum took in several families. At one point, dozens of children were sleeping on her living room floor, she said. Many in the neighborhood eventually moved, which took a toll on church attendance.

Calls to rebuild

The calls to rebuild and redevelop Seventh Street — and the other hard-hit “riot corridors” throughout the city — began almost immediately.

The National Capital Planning Commission, which began surveying the destruction as buildings still smoldered, reported nearly half the buildings on the street — 40 percent — suffered damage during the riots.

George Oberlander, an official with the planning commission, recalled setting out with a team of surveyors — clipboards and maps in hand — under the protection of National Guard troops to document the damage.

“I had been in destroyed areas. I lived in London when the Germans were bombing London, and so I’ve personally seen a great deal of destruction,” Oberlander, now 88, told WTOP. “And so it’s very similar to a bomb dropping … in terms of appearance.”

Officials and community groups drew up lofty plans.

A few days after being sworn into office in January 1969, President Richard Nixon even paid a visit to the riot-battered block of Seventh Street on which the church sat: “These rotting, boarded-up structures are a rebuke to us all, and an oppressive, demoralizing environment for those who live in their shadow,” he said, standing near a pile of ruins across the street from the church.

Still, actual rebuilding seemed to hit a standstill. By 1970 — two years after the riots — the city had only managed to construct 13 temporary playgrounds to fill in empty lots.

Soon after the riots, most of the block on which Mount Joy sat was condemned by city authorities.

In the meantime, the riot-torn areas became ghost towns or, worse, havens for crime.

“I didn’t want anything to happen to anybody’s child,” Bynum recalled. “So, we found this place up the street and we took it.”

‘Our church is gone’

The place up the street turned out to be a two-story brick storefront on N Street, just blocks away from the old church and still in the shadow of some of the hardest-hit areas of Seventh Street.

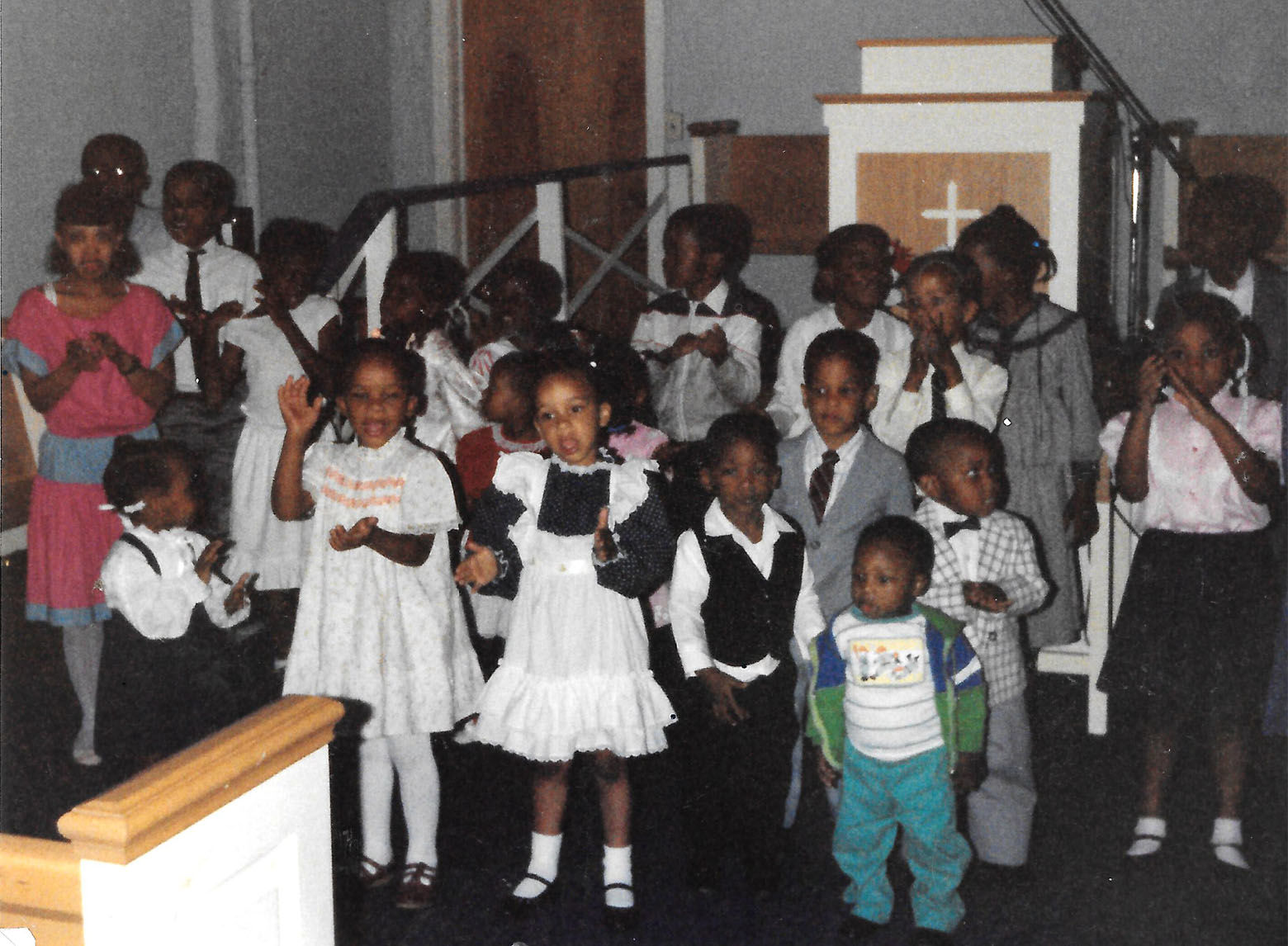

The congregation swelled with neighborhood children. The church started a little school in the afternoon to make sure they kept up good grades, Bynum said.

Very few of the children were taught they had potential, Bynum said. “They’re always just pushing ’em down,” she said. “But we began to say: ‘You can be whatever you want. It’s up to you to get started.’”

Like Seventh Street, the church’s new neighborhood was in flux. Even before the riots ravaged nearby streets, parts of Shaw had been proposed for large-scale urban renewal. The Redevelopment Land Agency would scoop up blighted property, raze dilapidated buildings and then sell the land to potential developers.

Mount Joy’s modest building on N Street wasn’t much to look at, but it wasn’t falling down. Nevertheless, city officials put the church’s building on the schedule for redevelopment. The city was supposed to help the congregation find a new home first, and proposed demolition was still months away.

Instead, the city mistakenly placed the church on a list of buildings to be demolished right away. Without notice, crews bulldozed the church on a Friday afternoon in July 1974.

Bynum had no idea until she turned down the street with a carful of kids on their way to services that evening. Driving up, one of the children spotted the pile of rubble.

“This child said, ‘Our church is gone,’” Bynum recalled. “I said, ‘Oh come on, stop kidding.’ And one of the mothers of the church said to me, ‘Oh yes it is. There’s not anything there at all.’ And I said, ‘They weren’t supposed to move us out.’ She said, ‘But I think they moved you out.’ So all we saw was a big old hole with muddy water and full of bricks.”

Children could see pieces of their church pews and piano keys peeking out from the rubble.

The Washington Post got wind of the blunder. “Misery at Mount Joy” was the headline below a photo showing two small children walking hand-in-hand past a small mountain of broken bricks.

“I guess there was a mistake,” a city official was quoted in the newspaper.

Mount Joy’s demise encapsulates the double-edged sword of redevelopment after the riots. Rebuilding often meant first tearing things down.

It was far from the only controversy over urban renewal in the city. Starting in the 1950s, according to D.C. historian Marya McQuirter, the redevelopment program razed some 500 acres in Southwest D.C., which was then a mostly residential neighborhood of poor black people.

Many of the homes were in poor condition; some lacked indoor plumbing. Still, when all was said and done, urban renewal in Southwest displaced some 23,000 residents — many of whom were forced into temporary “slum” housing in Southeast — and destroyed 6,000 businesses.

‘… a few pieces of clothing, a few dollars and a big pipe dream’

Bynum had faced trials before.

Born a preacher’s daughter in southern Virginia in 1924, Hattie Tucker had rebelled as a young woman against the faith of her father. She packed up and moved to New York City in 1944 to pursue her dream of becoming a jazz singer.

In the self-published memoir “The Making of a Minister,” Bynum described herself as “a very gullible country girl stepping off the bus at Port Authority with a few pieces of clothing, a few dollars and a big pipe dream.”

She found work as an “Annie Girl” at a speakeasy’s blackjack table. But she fell into hard-drinking ways, battled a heroin addiction and contemplated jumping in the “murky East River” before wandering past a storefront church above a neon-lit Harlem restaurant one night.

It was the headquarters of the Soul Saving Station for Every Nation Christ Crusaders of America, founded in 1942 by Rev. Billy Roberts, a self-described “railroad hobo” who’d had a religious awakening.

The newfound woman of faith moved to Washington in 1953 to live with her sister and started preaching on the street, at Seventh and O streets — right across from the massive brick market there. She drew crowds with her charismatic evangelizing.

“I just picked a street corner that was full of people and started by myself with a few songs that I learned at headquarters,” she wrote in her memoir. “I was a nightclub singer so I had to remember not to jazz it up too much.”

She began to gather crowds of regulars who asked whether she would start her own church.

Bynum, who found work as a housekeeper, married and eventually went to nursing school, was content to keep preaching from the corner, she said. But in November 1953, she secured permission from the home church in New York to officially open a Soul Saving Station in D.C.

A church for sale — ‘but we didn’t have any money’

After the church was forced from its location on N Street, Bynum continued holding services out of a few rooms at the YWCA on Rhode Island Avenue for a few years. The congregation shrank.

Still, the faithful held on.

One day, Bynum received a call about a nearby property going up for sale. It hadn’t yet hit the market. The realty company was surprised she’d heard about it, but invited Bynum and Elizabeth Addo, one of the other “church mothers,” to visit the building, she recalled.

The spacious three-story brick town house at M and 4th streets in Northwest had a main sanctuary, five classroom, four bathrooms, a full kitchen and a backyard.

“We thought, this is just what we wanted,” Bynum recalled. “But we didn’t have any money. I mean, you gotta bunch of kids and the organist … You know you don’t have any money.”

That is, until an anonymous donor stepped in. The donor — who directed Bynum and Addo to a downtown office building and conducted business entirely through an intercom — assured them they would find the down payment waiting for them at the realty office.

“I said, ‘Sister Addo, now, this is nothing but a setup,’” Bynum recalled.

Still, the down payment was there.

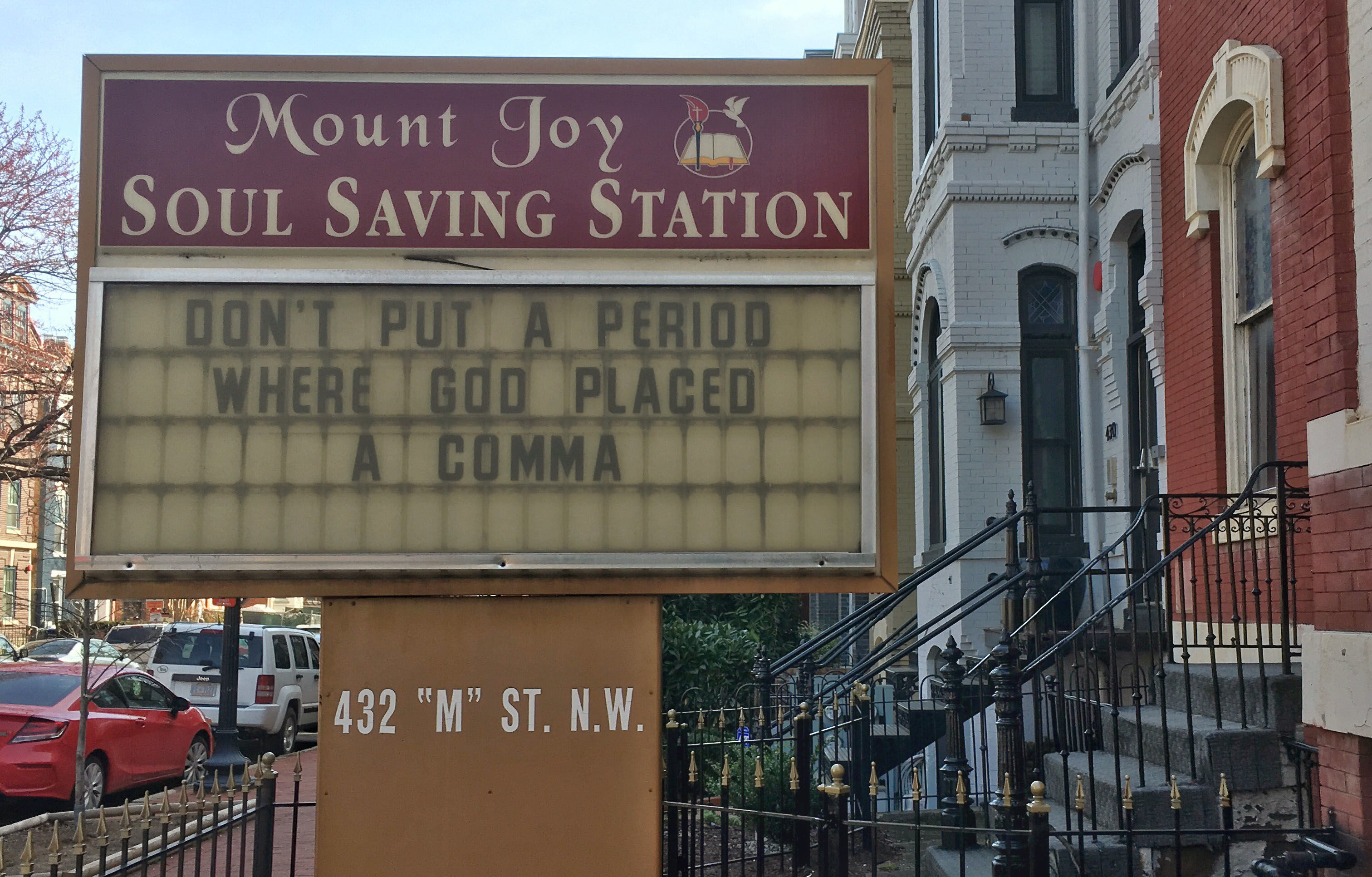

Mount Joy had a permanent home at last. The church has been on that quiet corner for more than 40 years.

50 years later

(View an interactive photo gallery showing how D.C. neighborhoods have changed since 1968)

The eruption of unrest in 1968 left scars on city neighborhoods for years.

But a half a century has wrought incalculable changes on parts of the city some residents didn’t think would ever fully recover.

The once riot-torn areas of 14th Street, Seventh Street and H Street Northeast are now three of the most vibrant areas of D.C.

The inner-city strip where Bynum once preached on street corners and ministered to poor neighborhood children is now dotted with rows of boutique shops, yoga studios and gleaming high-rise condos.

The former home of the Soul Saving Station — which once echoed with the strains of gospel chords — is now the “pop-up bar,” a novelty nightspot popular with the millennials who have flooded the city. (The bar’s recent themes have included cherry blossoms, “Super Mario” and “Game of Thrones”).

“I can’t even recognize it,” Bynum said.

The revitalization took decades. Still, as Mount Joy’s congregation well knows, redevelopment has come with downsides. Questions persist about whether all Washingtonians are truly sharing in the city’s newfound prosperity.

In the church’s home on M Street, the neighborhood is rapidly gentrifying.

John Bynum, Hattie Bynum’s son, who took over ministering duties full-time four years ago, said the church receives letters just about every month from developers seeking to buy the land.

“We’re not ready to sell at this particular time,” he said. “The time may come some day to do so. But right now, we’re willing to stay here.”

Toward the end of her memoir, summing up the history of her church, Bynum wrote, “Mount Joy has experienced many years of plenty and also of famine.” The metaphor could also accurately describe the history of the city itself in the 50 years since the riots.

Hattie Bynum has retired as pastor, but she’s honored as the church’s matriarch, remains a presence in the pews every Sunday and frequently travels all around the D.C. area to give guest sermons. A few years from the century mark, and after 65 years of ministry, Bynum shows few signs of slowing down.

To that, she credits “nothin’ but Jesus,” adding: “I just learned to just let the Lord have his way. And I don’t have a pain in my body or anything like that. I feel fine.”

(Video produced by Omama Altaleb)

More from the series, “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.”

- ‘Everything was on fire’ — remembering the DC riots 50 years later

- DC Uprising: An oral history of the 1968 riots

- Under fire: Retired police, firefighters remember 1968 flashpoints

- ‘The mayor saw it with his own eyes’ — a reporter chronicles 1968 chaos

- After the riots, an activist on trial

- How Ben’s Chili Bowl survived the 1968 riots to become a DC landmark (VIDEO)

- Shattered lives, unanswered questions 50 years after the riots

- Small DC church survived the riots. But then came the wrecking ball. Finally, a rebirth

- Then & Now: Powerful images show 1968 riot damage and rebuilt DC neighborhoods