This story is part of the WTOP series, “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.” Each day this week, we’ll tell the stories of the upheaval and tumult 50 years ago through the eyes of those who experienced it.

WASHINGTON — It’s been 50 years since the 1968 D.C. riots, in the wake of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King — a chaotic event that exposed the deep racial fissures in the city’s social fabric, caused millions of dollars of damage, ravaged neighborhoods and led to 13 deaths.

Here’s what happened, as recalled by the people who experienced it first hand.

(Text remarks have been condensed and edited for clarity. All titles reflect the speaker’s position in 1968.)

King’s killing rattles the city

Martin Luther King is in Memphis on April 4, 1968, to support striking sanitation workers. He steps out onto his balcony of the Lorraine Motel for a moment and is fatally shot by James Earl Ray, a white man.

VIRGINIA ALI, co-owner of Ben’s Chili Bowl

“Someone just ran into the door and said, “Dr. King has been shot.” Well, that’s unbelievable. Somebody has … a transistor radio, and we turn that on and we hear that, yes, he’s been shot and soon heard that it was fatal.

“So now they’re playing hymns on the radio, and people are coming in crying. How can this be? This very gentle man, nonviolently trying to make change for everybody. It was a sad, sad time. And of course that sadness soon turned to anger.”

JAMES CONNELLY, D.C. police officer

“I was in my house. I lived right down from No. 5 precinct, and it was a police family. And there was three of us. About 7, 8 o’clock at night … everyone’s knocking on the door. And the sergeant was there, and he says, ‘Get your clothes on. Get down to the precinct. Martin Luther King was just killed.’ And I thought, ‘Oh my God.'”

HATTIE BYNUM, pastor of a storefront church on Seventh Street and a nurse at George Washington University Hospital

“It was shocking, because we really couldn’t believe it … When I heard it, I was at work. And we couldn’t get home. And the hospital locked the door and everything. And we just had to stay there for a while.

“And I was concerned about my children, because it was time for them to get out of school. And I was just wondering, would they just go home and not stay in the street? But one of the members of the church thought about my children and she came over to my house and stayed with them.”

The first night

Crowds begin gathering at 14th and U streets. An effort to get stores to close down in honor of Dr. King spirals out of control. Crowds begin breaking store windows, clearing out shelves and setting a few buildings on fire. While there were shocking scenes of violence and destruction, others remember almost a carnival atmosphere.

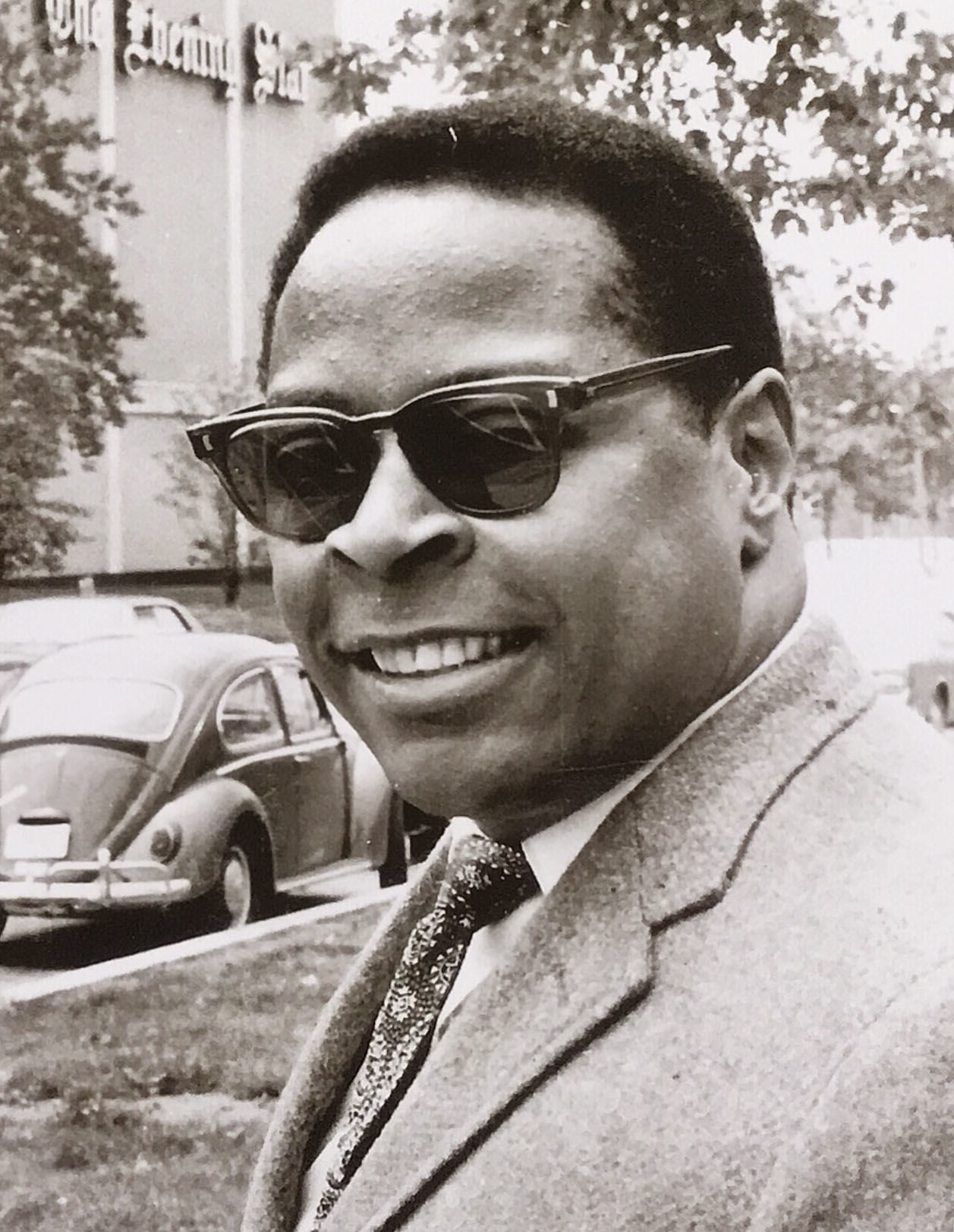

PAUL DELANEY, reporter for The Washington Evening Star

“It was a funny riot. I think it wasn’t frightening, because there was no resistance to it. Mainly youngsters, who were doing it, had free reign, so they weren’t threatened by the police.

“So there were no battles between cops and kids. It was almost a festival atmosphere. Kids laughing and joking, running from building to building, taking shoes or whatever they wanted. As a reporter, I didn’t feel threatened.”

MANUEL RIVERA, 16-year-old bicycle messenger for Western Union

“The young people had a chance to go in and grab stuff, clothing … I was with a couple people that were having fun. But I was afraid to go in there, because my mother didn’t play. There were people coming out with shopping carts with food in it and all sorts of things. For the young people, who really didn’t understand what was going on, it was a time of just having fun. There were times we would be out there on the street and some of my friends would try to entice the police to throw tear gas at us and some of them did. My mother finally made me come in later that night. It was a carnival-type atmosphere for some of the young people.”

Overwhelmed

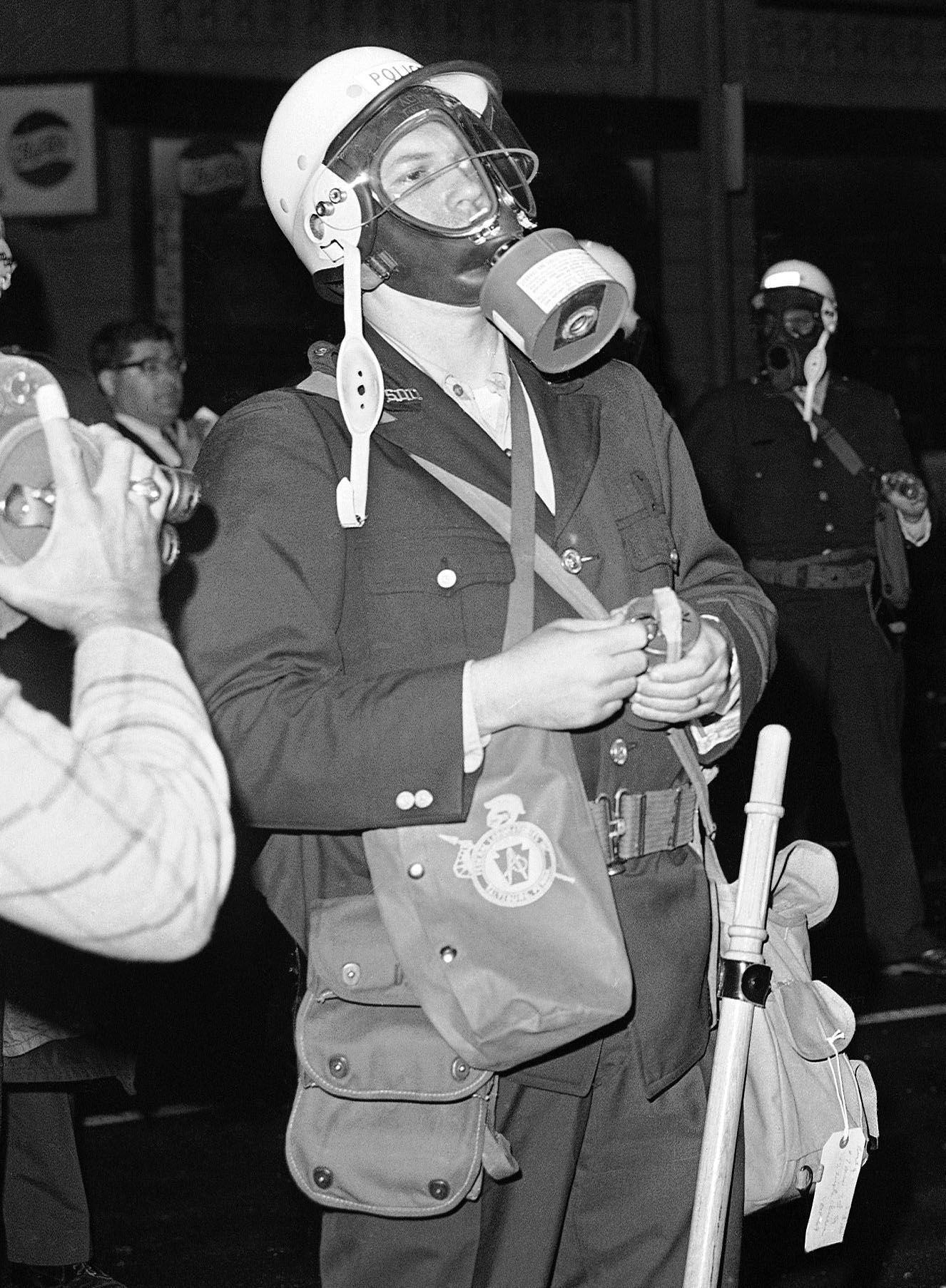

The police force is caught unaware when the violence broke out. Under orders from the mayor and the police chief not to shoot looters, officers also find themselves outnumbered and unable to even make arrests.

LARRY LINVILLE, Metropolitan Police Department Civil Disturbance Unit

“I remember when were first made members of the Civil Disturbance Unit, we were taken down to this big storeroom where all the weapons and chemicals and the tear gas was stored on shelves.

“And the people that were in charge of it at that time were telling us, you know, there was enough tear gas there to control any kind of a demonstration or riot.

“Well, in 1968, we ran out of tear gas the very first night.”

JAMES CONNELLY, D.C. police officer

“I remember that first night the police radio was so bad with yelling and screaming that the higher-ups said, ‘There’s no need to make any arrests, because it’s taking you off of the street and then there’s no room to put the people that are under arrest.’ So, your body was needed out on the street. So we didn’t really make any lock-ups because of it.”

The second day

Fires spread to Seventh Street in Northwest and H Street in Northeast. Downtown office workers see plumes of black smoke billowing up into the sky. The National Guard and Army troops are called in to the city.

GEORGE OBERLANDER, National Capital Planning Commission

“I remember seeing the smoke come up from my office. The planning commission’s office was at 17th and Pennsylvania Avenue.

“It was a Friday afternoon. And I looked out the window — the office director has the most windows usually in government agencies.

“And the smoke was rising in the 14th Street area … Finally somebody I think ran in and said there’s rioting going on. And we were excused; we were told to leave the city or go home.”

RUFUS MAYFIELD, activist

(Mayfield had been giving a speech at Indiana University when he got word Dr. King had been assassinated. He hopped on a plane back to D.C. the next day.) “When I flew into National, the place just looked like someone had dropped a bomb. The smoke, that dark smoke, was just billowing up.”

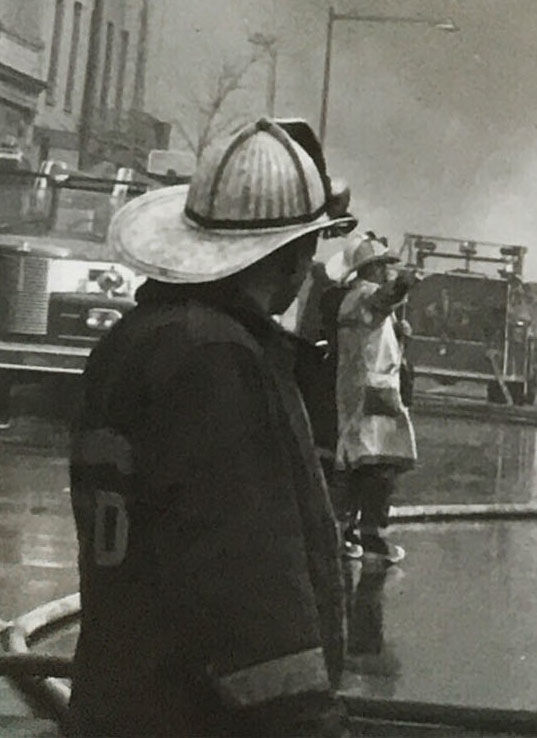

City on fire

The fire department faces a grueling workload. The fire chief puts in place “Plan F,” which recalls all firefighters to the job, half working days and half working nights. Over the weekend, firefighters will respond to more than 1,000 fires.

BILL EMBREY, D.C. firefighter

“We’d be fighting a fire in one building and one store or two stores up from us, you would just hear, like, glass break and an explosion, and fire’d be shooting out of the building.

“It was definitely a new experience … At one point in time, it looked like it was getting dark out at night, and you couldn’t see the sky. It was just gray and black smoke, just traveling south right down over our heads on 14th Street.

“You couldn’t even see the sky. It was just totally like a firestorm.”

DOUG WHEELER, D.C. firefighter

“We had no food. We didn’t think of that; we didn’t have time. One time, some grandmother came out — poor woman — cut the crusts off and made us these four little sandwiches and apologized. She said, “I don’t know what’s going on. But I see you all don’t have anything to eat.” So for 12 hours that was all the food we had, but what a sweetheart lady.”

FRANCES OLIFF, D.C. firefighter

“You never seen anything like that.

“At the night time … there was so much smoke, we walked right into the side of the ladder truck and didn’t know it was there … There’d never been anything like it before.

“The only thing you can compare it is maybe some of the fires they had in the brush fires and forest fires out in California, as far as the amount of the fire. You just had fires all over the city.”

The aftermath

Entire parts of neighborhoods were decimated. The National Capital Planning Commission sent surveyors out on the streets with maps and clipboards as buildings still smoldered and estimated the initial damage at $13 million.

GEORGE OBERLANDER, National Capital Planning Commission

“We were escorted by the military, the National Guard troops that were still there with their rifles and hand grenades on their belts, as I remember. … I lived in London when the Germans were bombing London, and so I’ve personally seen a great deal of destruction. And so it’s very similar to a bomb dropping on 14th Street in terms of appearance.”

STEVE SOUDER, D.C. Fire Department dispatcher

“The one thought that continued to come into my mind is that: Where will the people that lived in these areas now shop for food, get their milk, and all of the other things that you do in any neighborhood … because everything was absolutely destructed. And it reminded me of the photos that I had seen as a child of the bombing of London. When you saw all the buildings burned out and the rubble in the street. That’s exactly what it looked like in all of these affected areas. And I could not imagine what would happen to the areas or what would happen to the people.”

More from the series, “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.”

- ‘Everything was on fire’ — remembering the DC riots 50 years later

- DC Uprising: An oral history of the 1968 riots

- Under fire: Retired police, firefighters remember 1968 flashpoints

- ‘The mayor saw it with his own eyes’ — a reporter chronicles 1968 chaos

- After the riots, an activist on trial

- How Ben’s Chili Bowl survived the 1968 riots to become a DC landmark (VIDEO)

- Shattered lives, unanswered questions 50 years after the riots

- Small DC church survived the riots. But then came the wrecking ball. Finally, a rebirth

- Then & Now: Powerful images show 1968 riot damage and rebuilt DC neighborhoods