The Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism During World War II pays tribute to the 120,000 Japanese-Americans incarcerated in World War II, and the 20,000 who fought for the U.S. during the same war.

1/17

1/17

The five boulders in the water at the memorial represent the five generations of Japanese-Americans living in the U.S. at the signing of the 1988 Civil Liberties Act. (WTOP/Rick Massimo)

Aug. 15 marks the anniversary of the surrender that ended World War II — Victory over Japan Day or V-J Day. One of D.C.’s less-known monuments commemorates one of America’s darkest chapters during that history.

The Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism During World War II — tucked into the triangle formed by Louisiana Avenue, New Jersey Avenue and D Street in Northwest near Union Station — feels a bit like two monuments, because it serves two purposes.

It pays tribute to the 120,000 Japanese-Americans who were incarcerated during World War II because their ancestry was perceived as a threat, as well as the 20,000 Japanese-Americans who fought for the U.S. during the same war — some of whom came out of the very same camps to join up.

“The whole thing is baffling on so many different levels,” said Beth Kelley, the director of the National Japanese American Memorial Foundation.

While the anniversary of the Japanese surrender is Thursday, she said the emphasis in the community of incarcerees and their descendants is to look forward — and make sure the country remembers the lessons of history.

The memorial’s design, made by Davis Buckley Architects (whose D.C. work includes the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial, the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial and the Corcoran Gallery of Art), echoes its dual function. When you go into the main entrance on Louisiana Avenue, you walk through a narrowed entryway into what feels like a pen. That’s to evoke the sense of confinement, Kelley said. On the walls are the names of the incarceration camps and the number of people who were kept there.

2/17

2/17

On a brick wall beside an air raid shelter poster, exclusion orders were posted at First and Front streets directing the removal of persons of Japanese ancestry from the first San Francisco section to be affected by evacuation. (Courtesy National Park Service)

The incarceration of Japanese-Americans started not long after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, which brought the U.S. into the war.

On Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order No. 9066, which set the process in motion. The order doesn’t specifically mention Japanese-Americans — it declares that the secretary of war had the power to remove “any or all persons” from any area he deemed “military areas” at his own discretion. But those kept in what the government called “concentration centers” were almost solely of Japanese-Americans from the West Coast.

“Japanese-Americans, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, were all of a sudden a very obvious ethnic group that was in danger of being targeted because of their ancestral ties to the enemy,” Kelley said. “And that’s exactly what happened.”

3/17

3/17

Pins such as this one were popular following Japan’s attack on the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on Dec. 7, 1941. (Courtesy National Park Service)

It was a move inspired by racism — the number of German- and Italian-Americans incarcerated during World War II was microscopic in comparison, and many of them had trials. The fear inspired by the Pearl Harbor attack was used by many as a justification for the roundup.

A 1942 War Relocation Authority report pointed out that rumors of Japanese-American sabotage in Hawaii were “proved wholly false,” but the fact that many people believed them was considered reason enough for the move. The report claimed it was largely a matter of “public morale” — seemingly not bothering to count Japanese-Americans as part of the public.

Some advocates of incarceration didn’t even bother with that much of an excuse. An official with a California farmers association told the Saturday Evening Post: “We’re charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons. We might as well be honest. We do. It’s a question of whether the white man lives on the Pacific Coast or the brown men. … And we do not want them back when the war ends, either.” (He was known to have an economic incentive for wanting to discriminate as well.)

A Hearst Newspapers columnist wrote: “Herd ’em up, pack ’em off, and give ’em the inside room in the badlands. Let ‘em be pinched, hurt, hungry and dead up against it.”

4/17

4/17

In this March 30, 1942 file photo, Cpl. George Bushy, left, a member of the military guard that supervised the departure of 237 Japanese people for California, holds the youngest child of Shigeho Kitamoto, center, as she and her children are evacuated from Bainbridge Island, Washington. (AP)

By June of that year, the 120,000 Japanese-Americans were in the camps. About 70,000 of the detainees were American citizens, many of whom had never been to Japan. The War Relocation Authority report said, “While the remainder are aliens, it should be remembered that nearly all of them have been in this country for 18 years or more.” Some were discharged from the U.S. Army and headed straight for incarceration.

This didn’t bother an editorialist from the Los Angeles Times: “A Japanese American born of Japanese parents … notwithstanding his nominal brand of accidental citizenship, almost inevitably and with the rarest exceptions grows up to be a Japanese, and not an American.”

In the early 2000s, a pair of papers revealed evidence that U.S. census data were used to target Japanese-Americans. After the first paper, in 2000, Kenneth Prewitt, then the director of the U.S. Census Bureau, issued a public apology. (The Census Bureau told The Washington Post last year that laws have been changed since then to protect respondees’ information.)

5/17

5/17

The names of all 10 incarceration camps, and the number of people who were held there, are on the walls of the memorial. (WTOP/Rick Massimo)

The Japanese-American detainees were mostly from the cities and farming areas of the West Coast, and the 10 camps were “in the middle of nowhere,” Kelley said, in remote locations of California, Colorado, Utah, Arizona and Wyoming — near a railroad and a water source, but that’s about it.

Some were told they were being taken away for their own protection — indeed, perversely, the War Relocation Authority report cites “years of Caucasian discrimination” as a reason why Japanese-Americans might turn against their country. But as Kelley notes, they didn’t go voluntarily, and the guards stood in the towers with their guns pointed inside the camps.

“What kept them sane was these Japanese values of humility and going with the flow,” Kelley said. And they made life as normal as possible for their children, who are able to talk about the experience, as opposed to the adults, who felt shame and wanted to repress the experience.

This March 23, 1942, file photo shows the first arrivals at the Japanese evacuee community established in Owens Valley in Manzanar, California. (AP)

“We were citizens of this country,” said George Takei in a 2014 interview. The actor was incarcerated with his family when he was 5. “We had nothing to do with the war. We simply happened to look like the people that bombed Pearl Harbor.”

“My father told us that we were going on a long vacation to a place called Arkansas. It was an adventure. I thought everyone took vacations by leaving home in a railroad car with sentries, armed soldiers at both ends of the car, sitting on wooden benches. …”

“Children are amazingly adaptable. And so, the barbed wire fence became no more intimidating than a chain-link fence around a school playground. And the sentry towers were just part of the landscape. We adjusted to lining up three times a day to eat lousy food in a noisy mess hall. And at school, we began every school day with the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag. I could see the barbed-wire fence and the sentry towers right outside my schoolhouse window as I recited the words ‘with liberty and justice for all.’”

The prisoners lived in the camps for about three years — “Families were incarcerated together, unlike today,” Kelley said — and were released throughout 1945, with $25 and a train ticket each. “Often their property was plundered; their farms had been taken over by squatters, and they weren’t wanted back where they came from,” Kelley said. “It was a tragedy.” Many people knew there wouldn’t be anything left for them at home, so they went elsewhere.

7/17

7/17

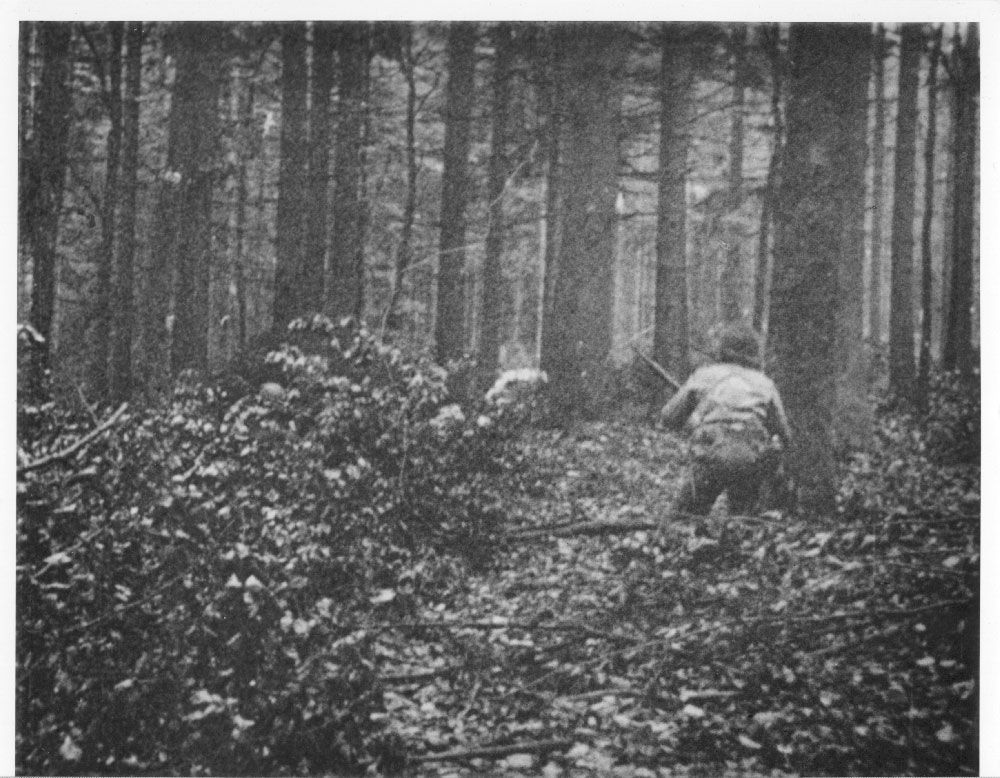

The fight to rescue the Lost Battalion in the Vosges Forest, October 1944. (Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

At the same time Japanese-Americans were being incarcerated, they were also valued members of the U.S. military during World War II, in Europe and the Pacific.

The 442nd Regimental Combat Team was the main Nisei (American-born people of Japanese descent) unit in the U.S. Army; it included the 100th Infantry Battalion, from Hawaii, where there were very few incarcerations and where Japanese-American volunteerism for the Army was “overwhelming.”

Some of the 442nd’s members had been in the Army before the war, been interned and then came back. Obviously, Kelley said, not everyone was crazy about the idea of serving the country that had incarcerated them and their families, but many saw it as a way to prove their patriotism, and the Japanese American Citizens League agreed, encouraging Nisei to sign up.

The 442nd fought in France, Italy and Germany. Their best known mission was the rescue of the Lost Battalion, which was surrounded by Germans in the Vosges Mountains, near the French-German border, in 1944. The 442nd suffered more than 800 casualties.

8/17

8/17

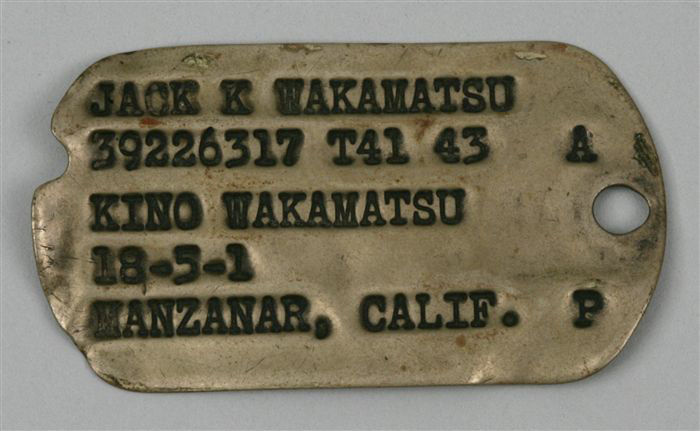

While Jack [Kino] Wakamatsu was serving in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, father Matsunosuke, mother Kino and sister Mary were behind barbed wire at Manzanar. (Courtesy National Park Service)

They were the most decorated unit of the war in view of their size and the duration of their service. They led 15 attacks and were awarded 9,500 Purple Hearts, 5,200 Bronze Stars and 21 Medals of Honor. They also suffered a 300% combat casualty rate.

About 6,000 Japanese-Americans also served in the Military Intelligence Service in the Pacific, where they interrogated POWs, translated captured documents and coaxed suicide fighters out of hiding. Gen. Charles Willoughby, Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s chief of intelligence, said the service saved “countless” American lives and shortened the war by two years.

“It showed how ridiculous the whole disloyalty thing was,” Kelley said.

As for the fears of sabotage, Kelley said: “There was absolutely not even one case. It was all lies. There was no sabotage; there was no spying. It just wasn’t there.”

9/17

9/17

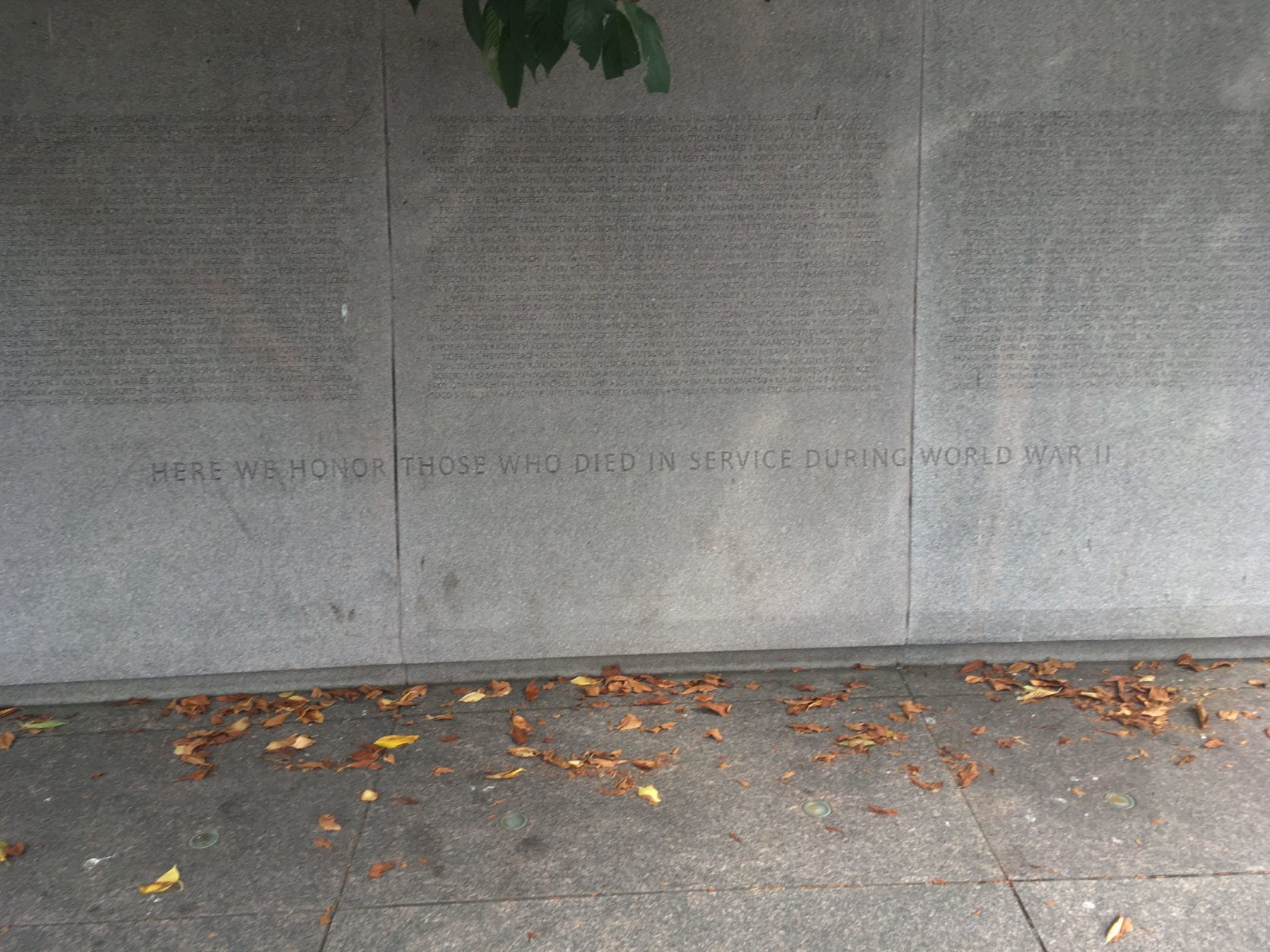

The names of the roughly 800 Japanese-Americans who died fighting for the U.S. in World War II are on the memorial. (WTOP/Rick Massimo)

About 800 Japanese-Americans were killed fighting for a country that held members of their ethnic group in captivity; their names are on the D.C. memorial.

10/17

10/17

The centerpiece of the memorial is a sculpture of two cranes caught in barbed wire. (WTOP/Rick Massimo)

11/17

11/17

From the back, the cranes’ wings resemble a torch. (WTOP/Rick Massimo)

In between the two areas of the memorial sits a sculpture by artist Nina Akamu that depicts two cranes entangled in barbed wire. But if you look at it from the back, Kelley said, the birds’ wings take the shape of a torch — a symbol of freedom, as well as the symbol of the 442nd.

12/17

12/17

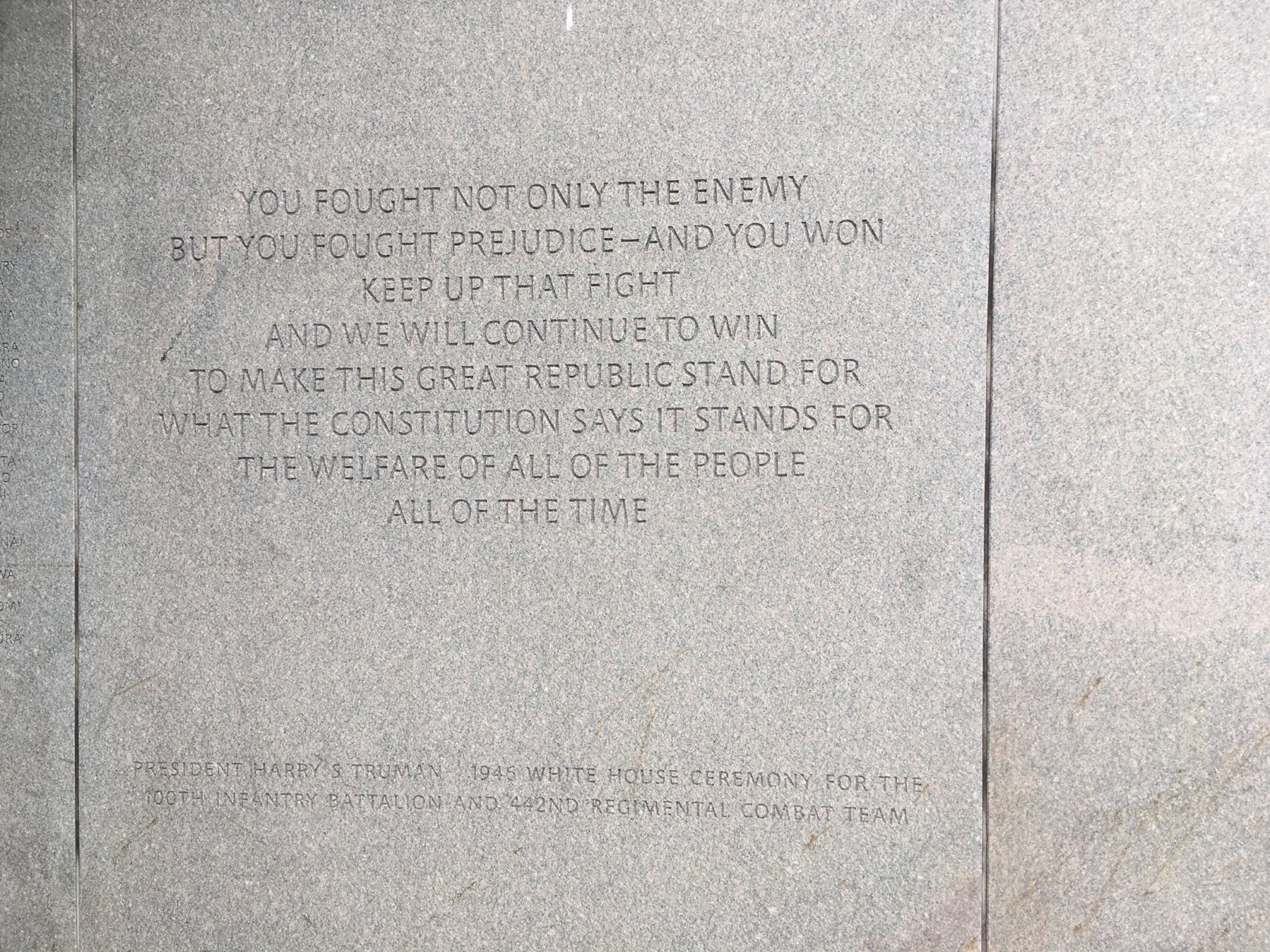

A quote from President Harry Truman during a ceremony for the 442nd. (WTOP/Rick Massimo)

Apologies for the incarcerations of Japanese-Americans began soon after the war. “The effect of those amazing soldiers was to bring improved civil rights for Japanese-American civilians after the war,” Kelley said. “They were held up as the heroes that they were.”

Presenting a citation to the 442nd, President Harry Truman said:

“You fought not only the enemy, but you fought prejudice — and you won. Keep up that fight and we will continue to win to make this great republic stand for what the Constitution says it stands for: the welfare of all of the people all of the time.”

13/17

13/17

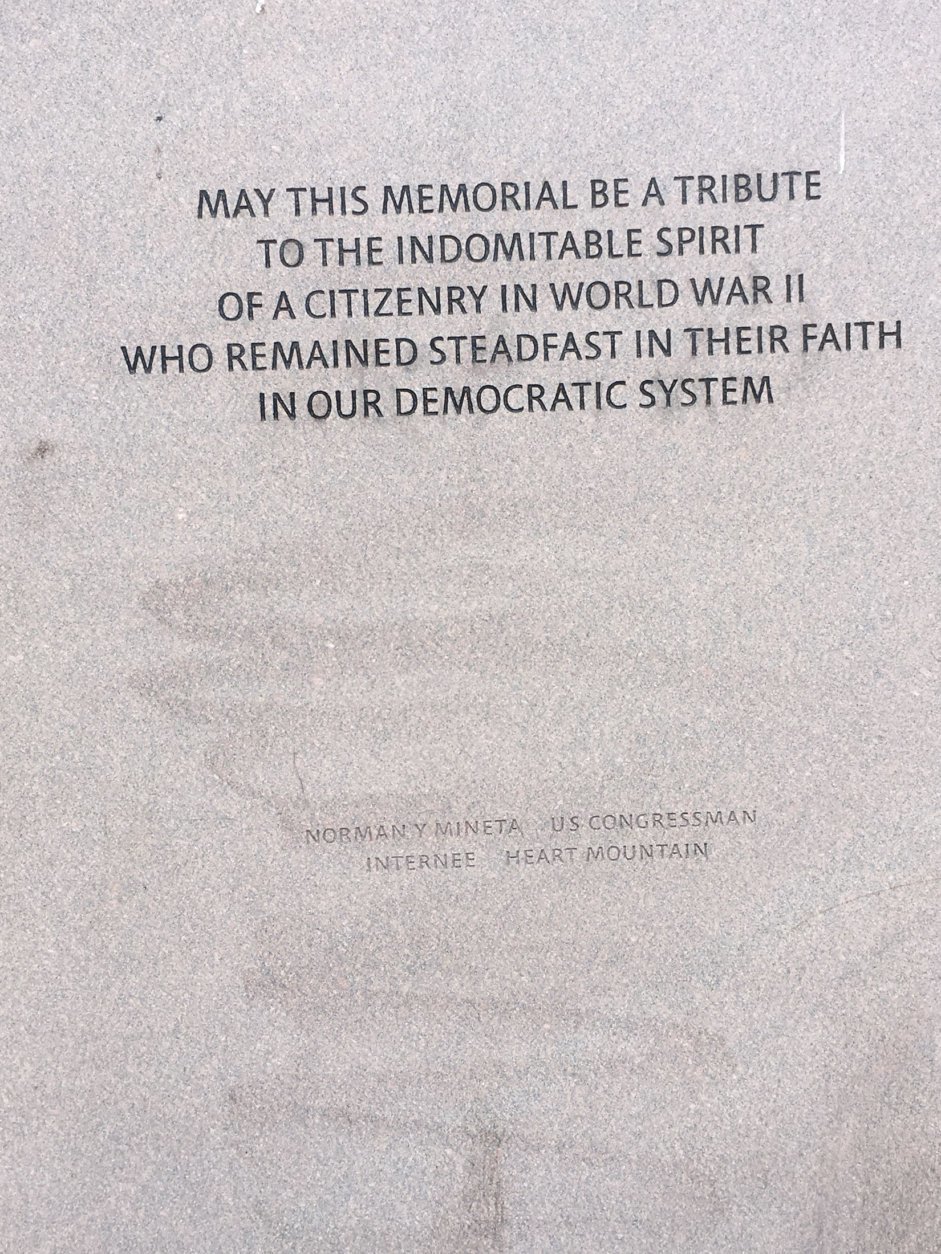

A quote from former congressman, treasury secretary and prisoner Norman Mineta at the memorial. (WTOP/Rick Massimo)

There’s also a quote from Norman Mineta, who was in a camp as a child and became a congressman and secretary of transportation:

“May this memorial be a tribute to the indomitable spirit of a citizenry in World War II who remained steadfast in their faith in our democratic system.”

14/17

14/17

The memorial also features a bell that’s tuned to resemble a Japanese call to prayer. (WTOP/Rick Massimo)

In 1983, a federal commission found that there was no military reason for the incarceration. In 1988, the Civil Liberties Act apologized for the injustice and gave each surviving prisoner $25,000 compensation. Kelley said many people gave their compensation check to the foundation to finance the construction of the monument, which opened in 2000.

15/17

15/17

Part of President Ronald Reagan’s remarks on the signing of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. (WTOP/Rick Massimo)

16/17

16/17

A quote from President Ronald Reagan at the signing of the 1988 Civil Liberties Act. (WTOP/Rick Massimo)

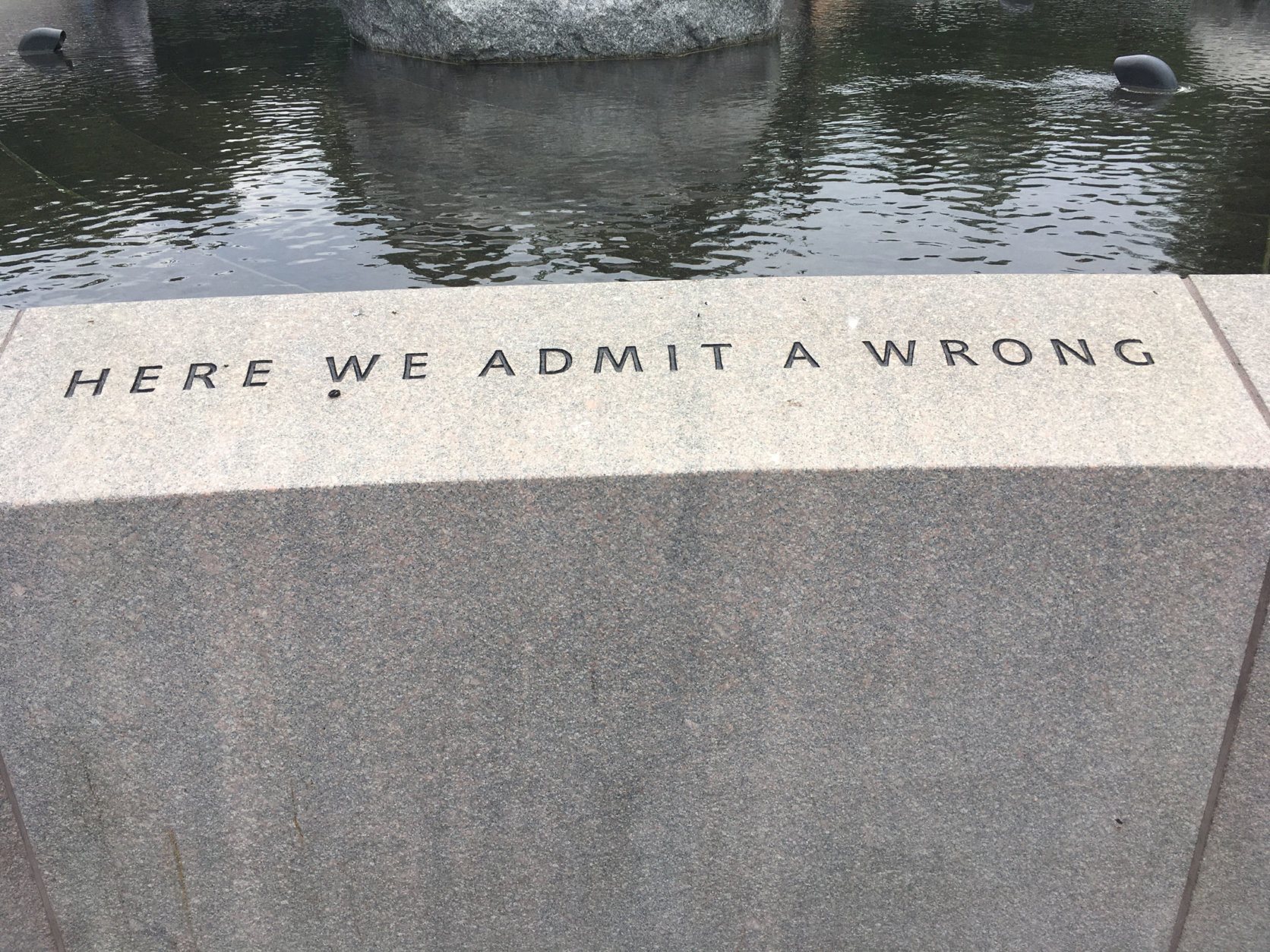

“Here we admit a wrong,” President Ronald Reagan said as he signed the Civil Liberties Act. “Here we affirm our commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law.”

17/17

17/17

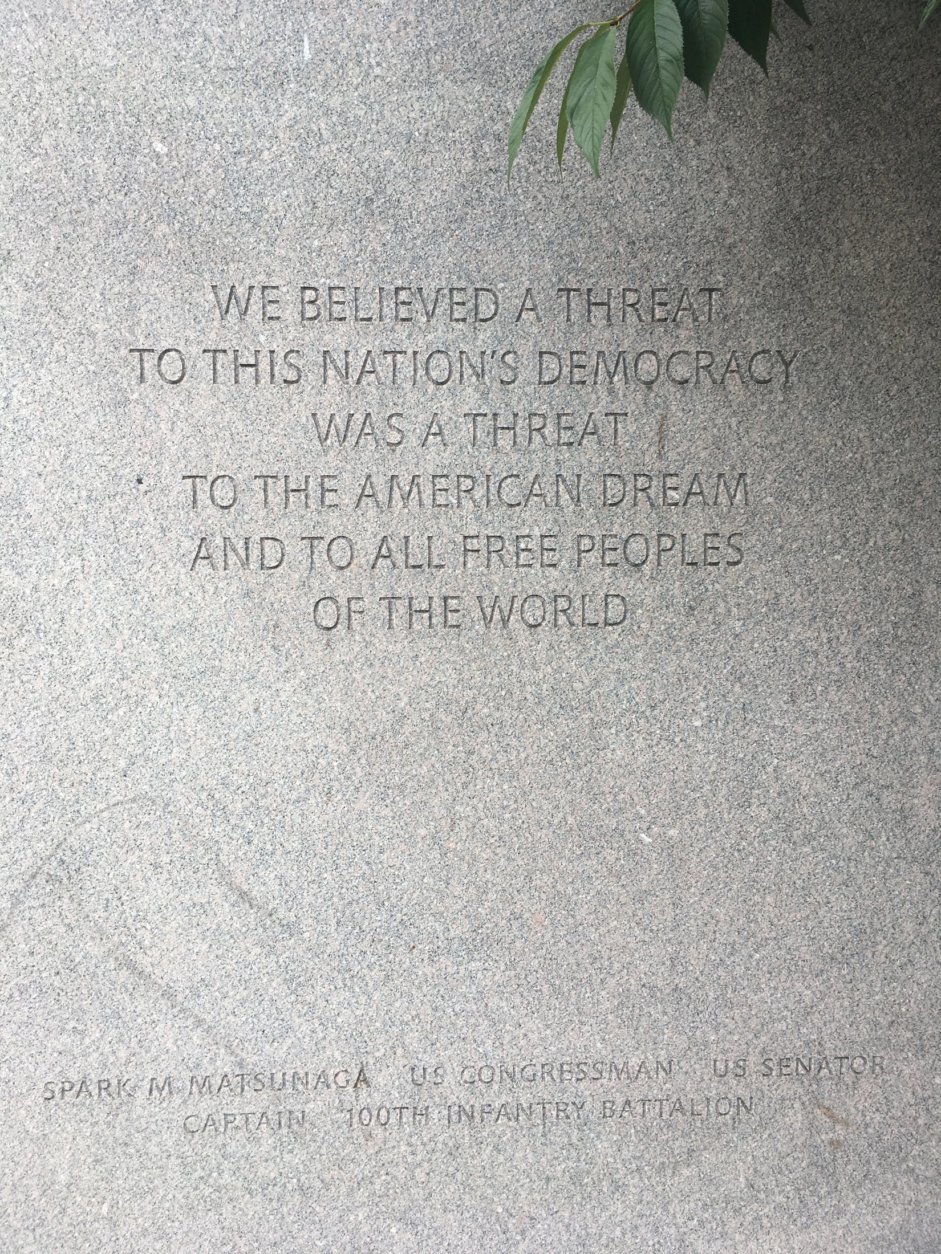

A quote from Army captain, congressman and senator Spark Matsunaga on the memorial sums up the patriotism of Japanese-Americans during World War II. (WTOP/Rick Massimo)

Kelley said the memorial is the only one in D.C., and perhaps the country, to contain an apology. “We have a nation that has the capacity to apologize for its mistakes. Let’s hope we never lose that.”