CENTREVILLE, Va. — Behind the million-dollar homes off Bull Run Post Office Road, the quiet woods hide what was once a counterculture rallying point that drew skateboarders, punk rockers and young people searching for acceptance to a remote area of western Fairfax County: a country club with the best halfpipe on the East Coast.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, the skateboard ramp, incongruously built on the grounds of what was then Cedar Crest Country Club, was an underground mecca with an energy that still reverberates for three filmmakers with local roots who remember what it was like to skate along its steely sides.

Now, a documentary film details the ramp’s story and its place in counterculture history. “Blood and Steel: Cedar Crest Country Club,” premieres Sunday evening at The State Theatre, in Falls Church.

‘An oasis’

Devoted skaters would travel hours to reach Cedar Crest, snaking down what were then poorly marked roads, often pitching tents on the grounds, contributing to a youth compound fueled by loud music and, often, drugs, alcohol and sex.

“When you drive down Bull Run Post Office Road, off Lee Highway, you didn’t know where you were going — you had to follow someone that was showing you the way,” said Mike Maniglia, the film’s director, who worked as a greenskeeper at the course so he could use the skate ramp daily.

Maniglia said the Cedar Crest skate ramp, which opened in 1986, served several purposes.

“You came to not only skateboard, but you came to escape,” said Maniglia. “You could drink; you could smoke all the pot you wanted; it didn’t matter. You were a kindred spirit to everyone that came out here.”

Film producer Frank Scheuring was a teenager living in Fairfax County when he first heard about Cedar Crest.

“Cedar Crest was an oasis, where all different types of people got together and got along,” Scheuring said. “It didn’t matter if you were a punk, skinhead, hippie, metalhead — they all came here to hang out and have fun.”

The ramp was built largely out of necessity, after a decline in the number of places skaters could practice in the early 1980s. Park owners often were concerned about insurance liability.

“We had about 12 skate parks in the D.C. area,” recalled film producer Mike Mapp, whose skating counterparts knew him as Micro. “When the parks went away, the skaters did not.”

Young skaters built makeshift ramps.

“We’re talking anything from a piece of plywood nailed to a telephone pole, to a homemade jump ramp which was a piece of wood and a cinder block,” said Mapp.

Despite the ingenuity, Mapp said, the homemade ramps didn’t make for a good skating experience.

“You put a layer of plywood on Friday and you get a weekend’s use of it, but by Monday it was all splinters,” Mapp said.

Cedar Crest Country Club owner Eugene Hooper allowed his son Mark to build the ramp on club property and financed the project.

Mapping a magical ramp

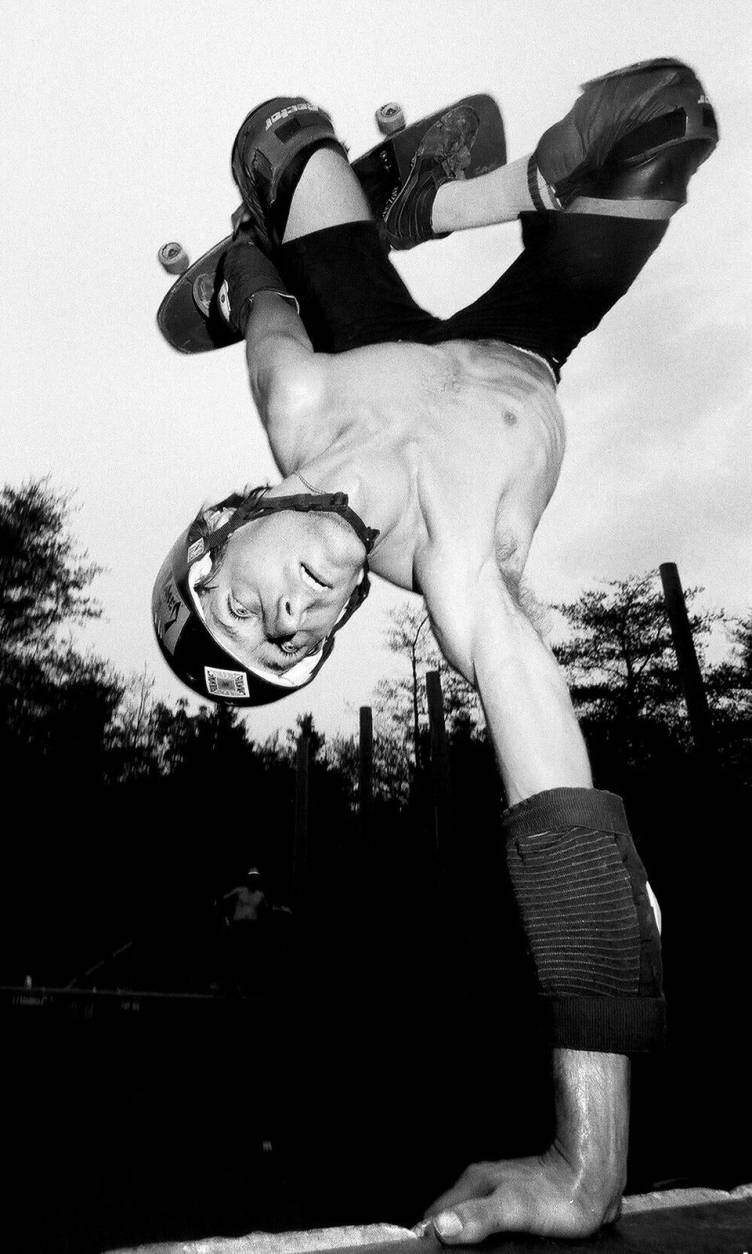

By 1985, Mapp had years of knowledge stored in his head about how to make a good ramp: “The measurements, the specs — the flat bottom length, the vertical length, width — and how to layer the ramp.”

“The coping protrusion, which is the top edge of the ramp that sticks out into the riding surface — it was defined at Cedar Crest that a 5/16th-inch bump is the magical amount: not too much and not too little,” Mapp said. “We knew when we got this opportunity, we were going to move into something that was light years ahead.”

The skating surface set the ramp at Cedar Crest apart from other ramps, Mapp said.

“You had 11-gauge steel on that ramp — no other ramp steel was that thick,” said Mapp. “It was faster, it was smoother than anyplace else.”

Decades before the internet, news of Cedar Crest Country Club’s ramp spread through word of mouth and skating magazines including Flipside.

Maniglia believes the ramp was among the best ramps in the world at the time, attracting visitors from Finland, Australia, England, France, Sweden, South America, Japan, Brazil, California, New Zealand, Poland and other Eastern European countries.

Within months, visitors would pay a $5 admission — or not — and stay all day. Or longer.

If they could find the place.

“Walking through the woods, when you’d get close you’d hear people skating and playing music from their car or boombox and you’d get chills,” recalled Scheuring.

At the time, the nearest house was miles away, so skaters made themselves at home. “You could go anywhere in the woods, and you’d stumble across someone’s tent or campground,” Maniglia said.

Skate jams

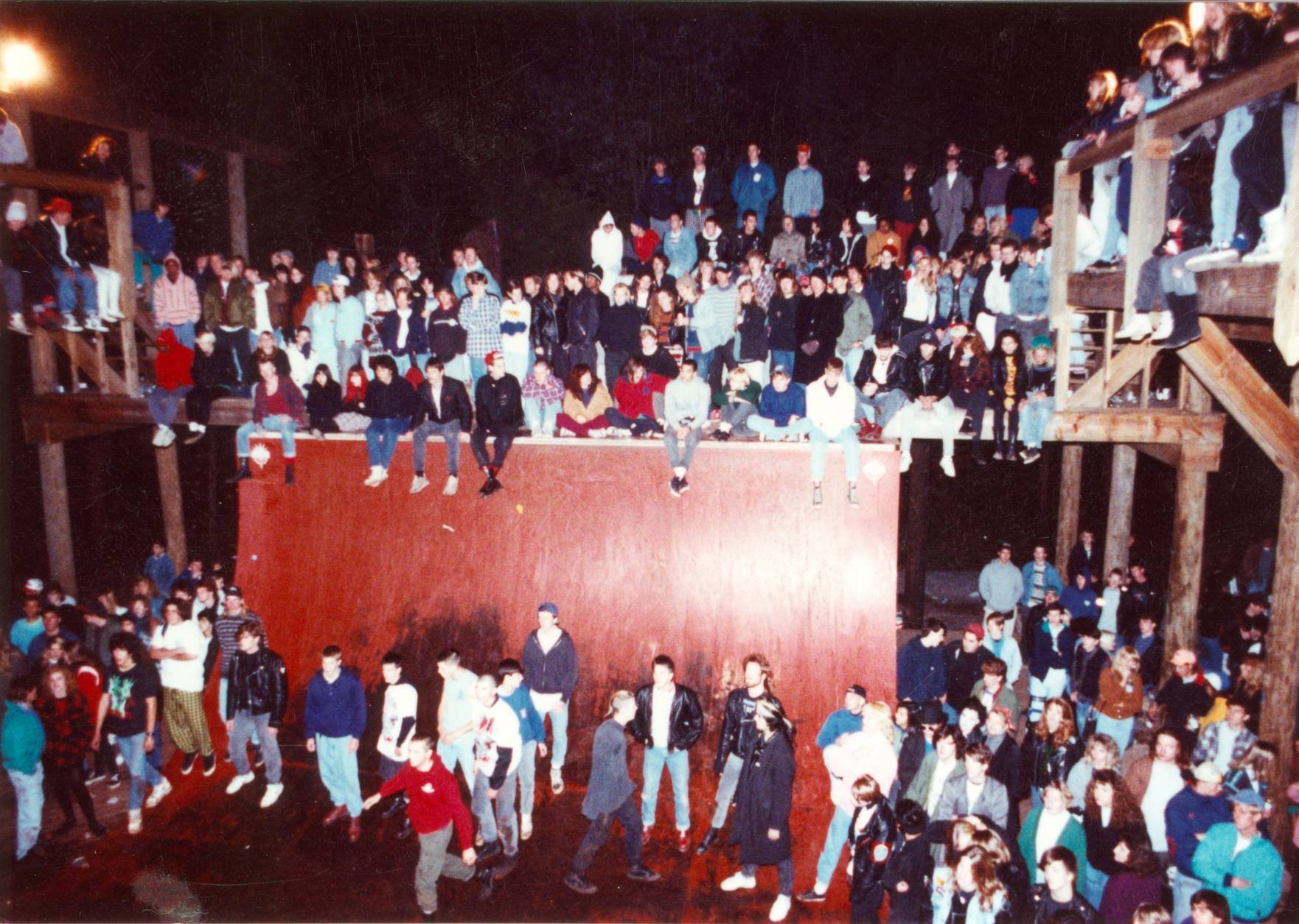

Soon, the skating community at Cedar Crest Country Club started hosting concerts.

“The day would start with a jam (skating) session, where there’d be a contest and you could win a hoodie or something,” said Maniglia, whose skating name is Grinch. “At night, the bands would start up.”

Bands from the D.C. punk scene, including Scream, played often at the Cedar Crest concerts. A band would set up their equipment at the flat bottom of the steel ramp, with fans flanking and sitting above the “stage” atop the structure.

(Scream and Red Hare will both perform at Sunday’s movie premiere at The State Theatre. More information on the screening is available at the film’s website.)

“Sometimes we had the bands playing on the mini ramp, and the big skating ramp kept going into all hours of the night — and morning,” Mapp said.

Although there was some tension between the country club members and those frequenting the skate ramp, members, skaters and neighbors generally coexisted, Maniglia said.

“When the police came, they were in awe,” said Maniglia. “They couldn’t believe this little oasis of counterculture existed. Remember 30 years ago, it was like, ‘Skateboarding, what’s that?’”

Occasionally skaters were seriously injured on the ramp, and organizers were concerned about inebriated young people driving.

“Nobody wanted you to get a DUI because you could drive off the road,” said Maniglia. “It’s a tapeworm of a road.”

Turn out the light

Toward the end of the 1980s, after coverage from news outlets including CNN and The Washington Post, the popularity of the ramp likely contributed to its downfall.

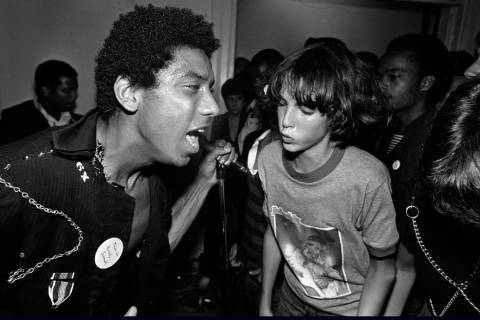

In the film, D.C. hard-core punk pioneer Ian MacKaye — an avid skateboarder — said his then-new band, Fugazi, was invited to play at Cedar Crest in 1989.

“We were reticent,” MacKaye said. “I had heard of Cedar Crest, and it was pretty legendary at that point.”

Eventually, Fugazi agreed to play and showed up in October 1989.

As he watched the opening bands, MacKaye recalled seeing two police officers approach the stage and order the electric power turned off, which plunged the entire area into total darkness.

As more police cars arrived, with helicopters overhead, the evening’s concert was shut down.

“The concert component of that evening was over and done. After the cops, crowd and helicopter had departed, the chain across the ramp was removed, broken glass swept and the skate session resumed,” MacKaye told WTOP. “Quite a night.”

Mapp said the end of the Cedar Crest Country Club ramp was near.

“They were heading toward bankruptcy and one of the things they decided to do was shut the ramp down,” Mapp said. “The ramp existed for the next year and a half, but it was never to be like the grand old days.”

By 1992, Cedar Crest was foreclosed and torn down.

Searching, 25 years later

Earlier this week, a WTOP reporter traveled with Maniglia, Mapp and Scheuring to Centreville in search of the ramp’s remnants.

Over the years, development encroached along the streets off Bull Run Post Office Road that once led to the ramp, and almost all evidence of the structure was carted away.

Parking their SUVs at the end of a cul-de-sac, the three filmmakers traipsed through now-overgrown woods, looking for signs of what was once a home away from home.

Finally, after 30 minutes, with the help of neighbors on ATVs, Mapp exclaimed, “That’s it!”

He had recognized the lay of the land and a concrete slab he had erected for the ramp.

The film’s producers noted the irony of their modern search for their musical and skating past.

“In anyone’s lifetime, when you can step into a time capsule and relive your youth, especially one you’re so fond of, there’s a welling of emotion,” said Maniglia. “So, walking down this path, finding those wooden pilings, standing with all of you is very emotional.”

Scheuring said his experiences at Cedar Crest led to his career in music and audio engineering.

Mapp, who is now a master builder of skate parks, had mixed feelings.

“When I look around, and the country club is no longer there, and the houses are being developed, and your baby has been mowed down, it’s not easy,” said Mapp. “Yet, we’ve found it, and here we are — nothing lasts forever.”

Except, sometimes, memories. And movies.

“We’re still kids — this is a kid thing,” said Micro, aka Mapp. “Obviously, we don’t want to be adults.”

Watch the trailer for “Blood and Steel: Cedar Crest Country Club”: