New York City police raided Stonewall Inn around 1:20 a.m. on Saturday, June 28, 1969. Same-sex sexual activity between consenting adults was illegal in New York. So was cross-dressing. Within hours, hundreds of drag queens, transgender people and other members of the LGBTQ+ community took to the streets in the Stonewall riots to call for their right to assemble and live in their truth.

More than 200 miles away, the call was heard.

“It was an earthquake in Washington,” said Charles Francis, president of the Mattachine Society of Washington D.C., a reincarnation of the first gay civil rights organization in the District.

The Stonewall riots energized an LGBTQ+ rights movement that had started years earlier in the District. On April 17, 1965, 10 members of the original Mattachine Society, co-founded in 1961 by Dr. Franklin E. Kameny and Jack Nichols, picketed on the sidewalk in front of President Lyndon Johnson’s White House. The men wore neckties and jackets, and the women wore skirts. Their intention, Francis said, was to look non-threatening, inoffensive and employable.

“Then comes Stonewall and these are not neckties and skirts,” Francis said. “These are youth in the street looking like the Greenwich Village citizens [that] they were in jeans and T-shirts and yelling and rioting. It was a different style and a different generation.”

Fifty years after the Stonewall riots, D.C.’s LGBTQ+ community is celebrating Pride month. A lot has changed since 1969 to make the District a safer place for LGBTQ+ people, but that progress has not come easily.

‘No safe spaces’

Same-sex sexual activity was illegal in D.C. until 1993. Under the Eisenhower administration, federal employees who were members of the LGBQ+ community were considered a security threat, allegedly, because they could be blackmailed with evidence of such activity.

“There really were no safe spaces in D.C. in the ‘50s and ‘60s and even part of the ‘70s,” Francis said. “People know that there were gay and lesbian bars, but you were still looking over your shoulder, especially if you had a security clearance.”

Still, the District has a rich history of bars and clubs that cater to the LGBTQ+ community. Ed Bailey is a co-owner of two such bars, Number Nine and Trade. A D.C. native, he graduated from Sidwell Friends High School and attended Georgetown University for graduate school.

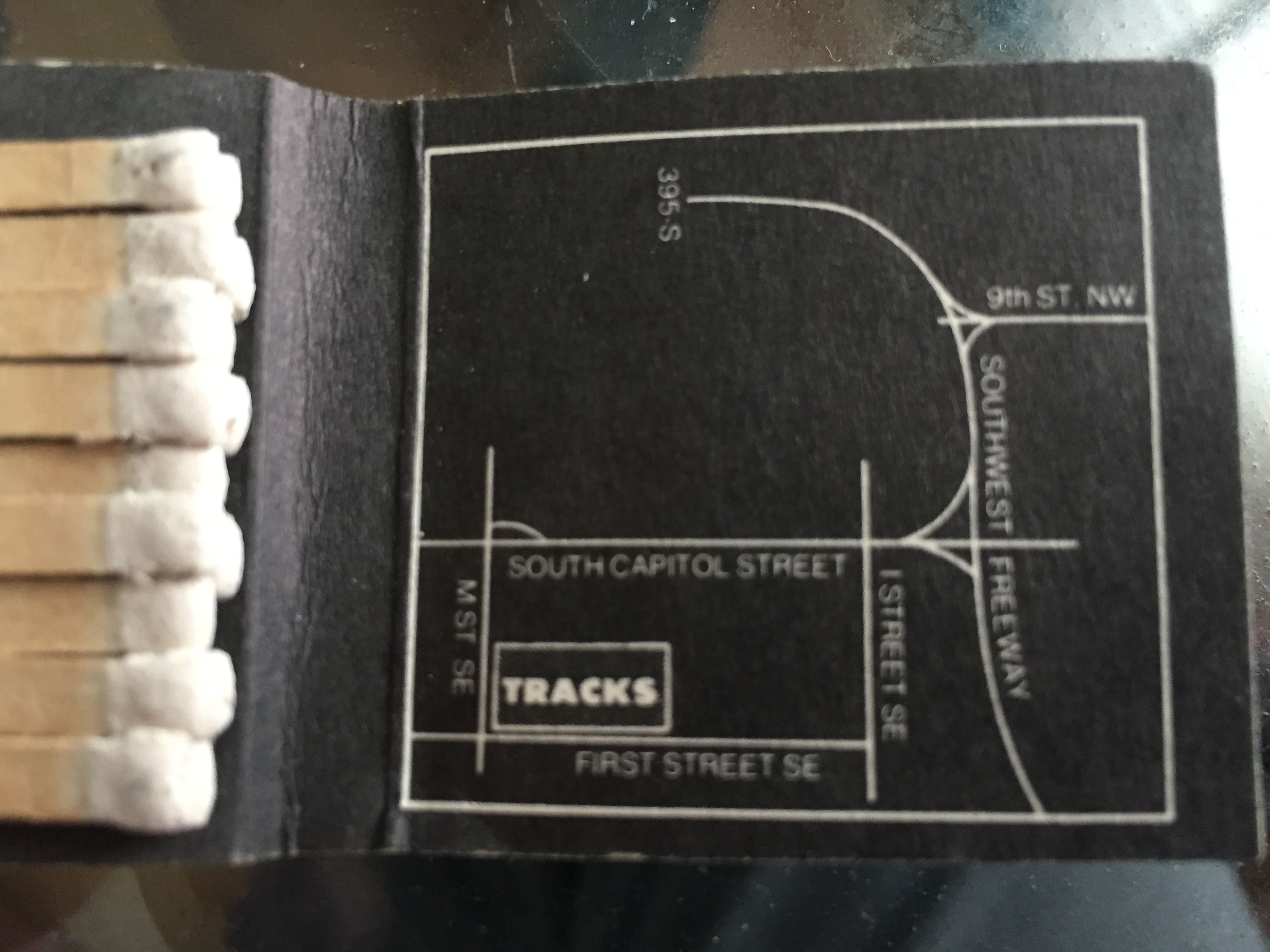

When he came back from college during his undergraduate years, he found Tracks, a gay nightclub on M Street SE in Navy Yard. He started working there as a DJ, and eventually became a joint owner of the club.

“The fact that I was part of trying to help to provide a place for people to be, to enjoy themselves and to escape the other parts of their life that maybe weren’t as much fun … just kind of felt so satisfying, it felt so necessary and it’s very gratifying to be a part of something like that,” Bailey said.

Places like Tracks weren’t just a source of entertainment, but also information for the LGBTQ+ community. Before social media, people met in person to discuss current events and news, often from the city’s one major LGBTQ+ outlet — The Washington Blade. So bars and clubs became centers of communication, networking and activism, said Francis. He remembered attending activist events at Pier Nine, a megadisco on Half Street in Southeast D.C. that had phones on the tables that patrons used to call one another.

One such event was a fundraiser to fight Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign in Dade County, Florida — which sought to overturn a local ordinance prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation.

“It was an exciting time to see the movement grow as it faced its first major challenge in Anita Bryant,” Francis said.

The LGBTQ+ rights movement found roots in underdeveloped parts of D.C., such as Dupont Circle and Navy Yard. Bailey said the demand from the LGBTQ+ community for safe places to exist and organize allowed it to thrive where others could not. But as the community made strides in its fight for acceptance, D.C. became more integrated.

“Queer people who felt comfortable living around other queer people lived in certain neighborhoods,” Bailey said. “But over time the concentrations of those communities have spread out as attitudes have changed about the community in general and there’s wider acceptance.”

LGBTQ+ people of color: a duality

Even within a marginalized community, there was still discrimination. Black LGBTQ+ people were not always welcome at white-owned bars and clubs, or were only welcome on certain nights.

“It was segregated, but nobody talked about it. It was just the way things were,” said Sheila Reid, director of Mayor Muriel Bowser’s Office of LGBTQ Affairs.

LGBTQ+ people of color in the District built their own spaces, like the Clubhouse, a social club on Upshur Street in Northwest D.C. It was there in 1991 that the legacy of D.C.’s black pride began. For years, the Clubhouse had hosted an event on Memorial Day attended by people from out-of-town. When the club closed down after multiple staff members died from AIDS, three men decided to continue the tradition. Welmore Cook, Theodore Kirkland and Ernest Hopkins held a fundraiser to raise awareness of HIV/AIDs and money for prevention and treatment. Eight hundred people showed up at Banneker field across from Howard University for the event, which became the first Black Pride in the country.

“People don’t realize that when you’re of color and you’re LGTBQ there’s a duality,” said Earl Fowlkes, president and CEO of the Center For Black Equity, Inc. “I think the larger population, especially in African American communities think that if you become LGBTQ, become queer, that you stop being black.”

The marginalization of LGBTQ+ black people from both parts of their identity brings unique challenges. According the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, black gay and bisexual men are more affected by HIV than any other group in the United States. In 2017, black gay and bisexual men accounted for 26% (10,070) of the 38,739 new HIV diagnoses, and 37% of new diagnoses among all gay and bisexual men in the U.S. and dependent areas.

Gentrification has also hit harder on a population already suffering from higher rates of disease. As many people of color are pushed out of their neighborhoods into Maryland and Virginia, Fowlkes said it has become harder for their community to gather regularly.

“One of the special things about Black Pride, all 55 Black Prides around the world, is that we’ve created a safe space for people to celebrate being black and being LGBTQ, and they can be both of things without having to compromise one or the other,” Fowlkes said.

Still, Fowlkes says the District has come a long way.

“Now younger people have far less hangups of going to places that are more integrated — they’ll just show up,” he said. And they’ll go to [predominately] straight black bars and also show up as well, they don’t care, they just want to show up and have a drink.”

Not just ‘white, gay men’

The path to progress has not been equal for all members of the LGBTQ+ community.

Earline Budd is a case manager at HIPS, a support and advocacy group for sex workers and drug users, and a founding member of Transgender Health Empowerment, Inc. (T.H.E.). A transgender woman, she was kicked out of her home at 13 and put in government custody under the People in Need of Supervision (PINS) program.

She spent years at a series of youth detention centers before she was released. Budd said she found her community on the streets, under the guidance of older transgender women and activists like Dr. Kameny. It was her last refuge in a city where even LGBTQ+ black spaces like the Clubhouse had closed their doors on her.

“The Clubhouse was a place where [transgender people] per se were not welcome, at least in female clothes,” Budd said. “Back in the years we were told, ‘OK, you need to take off those girl clothes, you’re not coming here like that, if you want to party you come in here as a dude.’”

Budd said the scars of that rejection remain visible in the transgender community today. The Clubhouse later began allowing transgender people to enter regardless of their apparel. But progress has not erased a painful history.

“We are still divided, where there are some gay men that do not accept transgenders, there are lesbians that don’t accept transgenders, and then, of course, because of what we’ve been through in terms of being disenfranchised, we have issues with their community,” she said.

Transgender people are still more likely to be affected by homelessness and violence. According to the National Center for Transgender Equality, one in five transgender people have experienced homelessness at some point in their lives. In a 2013 report, the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs found that transgender people were much more likely than non-transgender people to experience threats, intimidation, harassment, discrimination and sexual violence.

At least eight transgender people were killed this year, according to the Human Rights Campaign. One of them, 27-year old Ashanti Carmon, was shot dead in Prince George’s County on March 30. Just blocks away, 23-year-old Zoe Spears, was also shot to death on June 14. Prince George’s County police say the two women knew each other.

“I think it took a long time to add the ‘T’ [in LGBTQ] and to respect the ‘T’,” said Reid of the mayor’s office. “If you talk about who started the Stonewall uprising, it was the transgender community. They didn’t use the word transgender at the time, but that’s exactly who it was — it wasn’t just a group of white, gay men.”

‘What else do you want?’

Same-sex marriage was recognized in the District on Dec. 18, 2009. It was more progressive than laws in other parts of the country at the time, because it applied to anyone getting married in D.C. — not just residents. People came from around the country to wed in D.C., even though their own states would not recognize their union.

But marriage equality isn’t a stopping point for Reid, who says she is regularly asked why she is still advocating for LGBTQ+ rights even after marriage equality was established nationwide by the Supreme Court in 2015.

“Marriage equality is kind of symbolic, but at the end of the day if you can’t survive, if you’re living day-to-day, paycheck-to-paycheck, marriage is not even on your radar. You’re just trying to make sure that you got food on the table the next day,” she said. “Paying for a wedding is a luxury.”

With progress comes renewed challenges. Bailey said as grateful as he is for the rights the community has gained, he feels a certain loss as well.

“The oppression that we felt as a community gave us the strength to bond together and fight for ourselves as a community. And as that fight sometimes feels like it’s a slightly less of a fight in general, the bond of the community feels like it loses a little of that oomph that it used to have,” he said.

But as the LGBTQ+ rights movement reinvents itself, Bailey said he is hopeful that it is becoming a more inclusive movement that is more aware of the issues its more marginalized members face.

And so it continues.

“If you blink, all of that progress will be gone in a minute, so you really have to keep your eye on the prize and not get too comfortable and rest on your laurels,” Reid said.

“We take nothing for granted, and we are proud to be leading the fight.”