WASHINGTON — It’s not easy to keep a business going for 60 years, and it’s hard to become a local landmark beloved by everyone from presidents to the neighborhood kids. But Ben’s Chili Bowl has managed both.

The history-laden eatery stands as a testament not only to its own history but that of the neighborhood around it. Over the past 60 years, the area around 12th and U streets in Northwest D.C. has gone from a bustling entertainment and cultural district known as Black Broadway, to a battle-scarred ruin in the wake of the uprising following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to a thrumming, pricey area today.

And through it all, Ben’s Chili Bowl has been one of the constants.

In the last few years, the Ben’s empire has expanded greatly, with new locations in the District and Virginia, including some spots befitting its status as a regional icon. But at the original U Street location, patrons still eat from the well-loved menu of half-smokes, chili cheeseburgers, shakes and more under the photos of entertainers, intellectuals, sports stars and presidents who have headed to Ben’s over the decades.

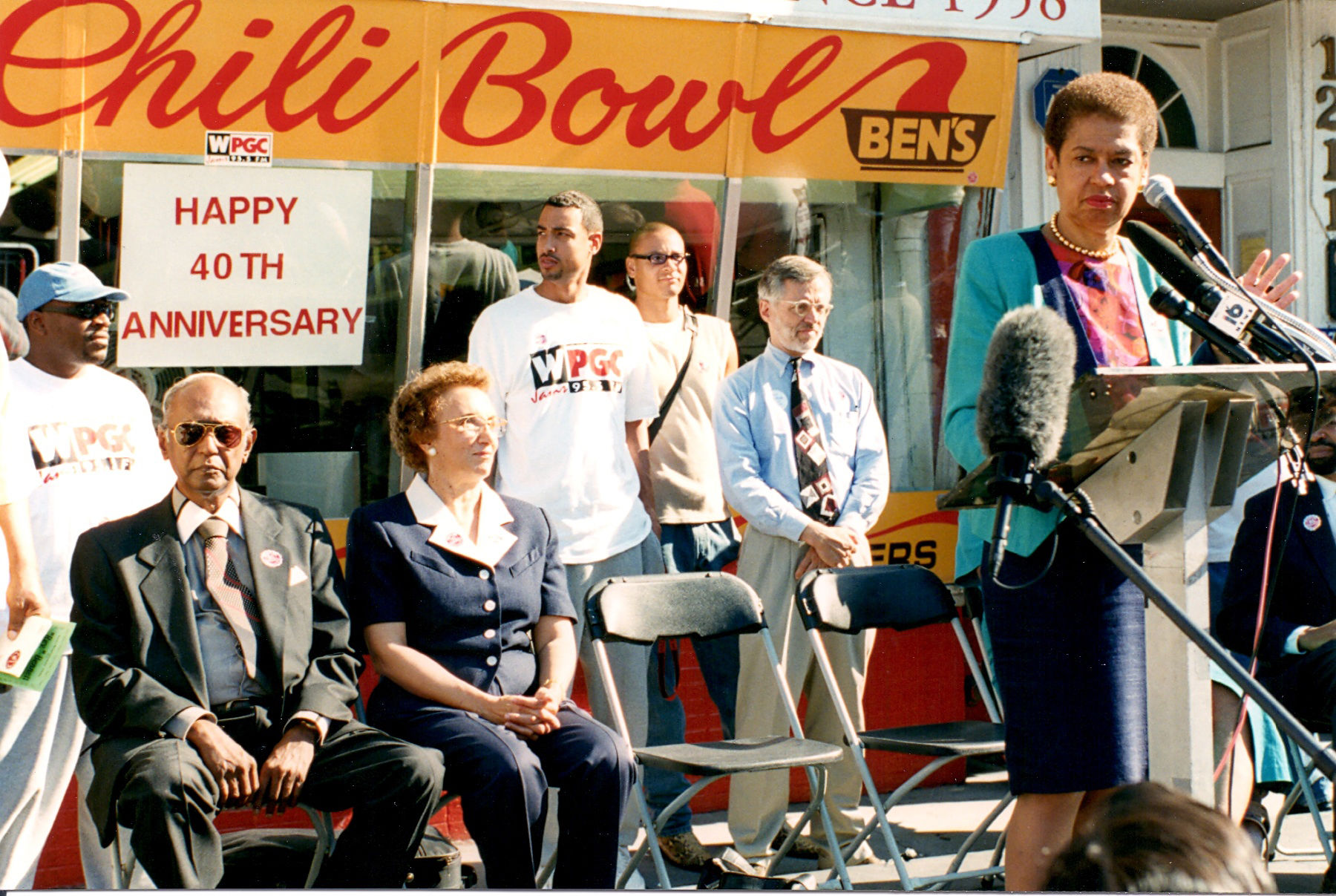

To celebrate the 60th anniversary on Wednesday, D.C. is throwing a ceremony renaming the 1200 block of U Street as Ben’s Chili Bowl Way.

But before the ceremony begins, co-founder and owner Virginia Ali traced the history of Ben’s, remembering what has and hasn’t changed over the restaurant’s six-decade run so far.

A close-knit community

Virginia Ali said her husband, Ben, came to the U.S. from Trinidad to learn dentistry. In graduate school at Howard University, however, a back injury forced him to abandon his studies. He had restaurant experience from his college days, a recipe for chili and a desire to work for himself.

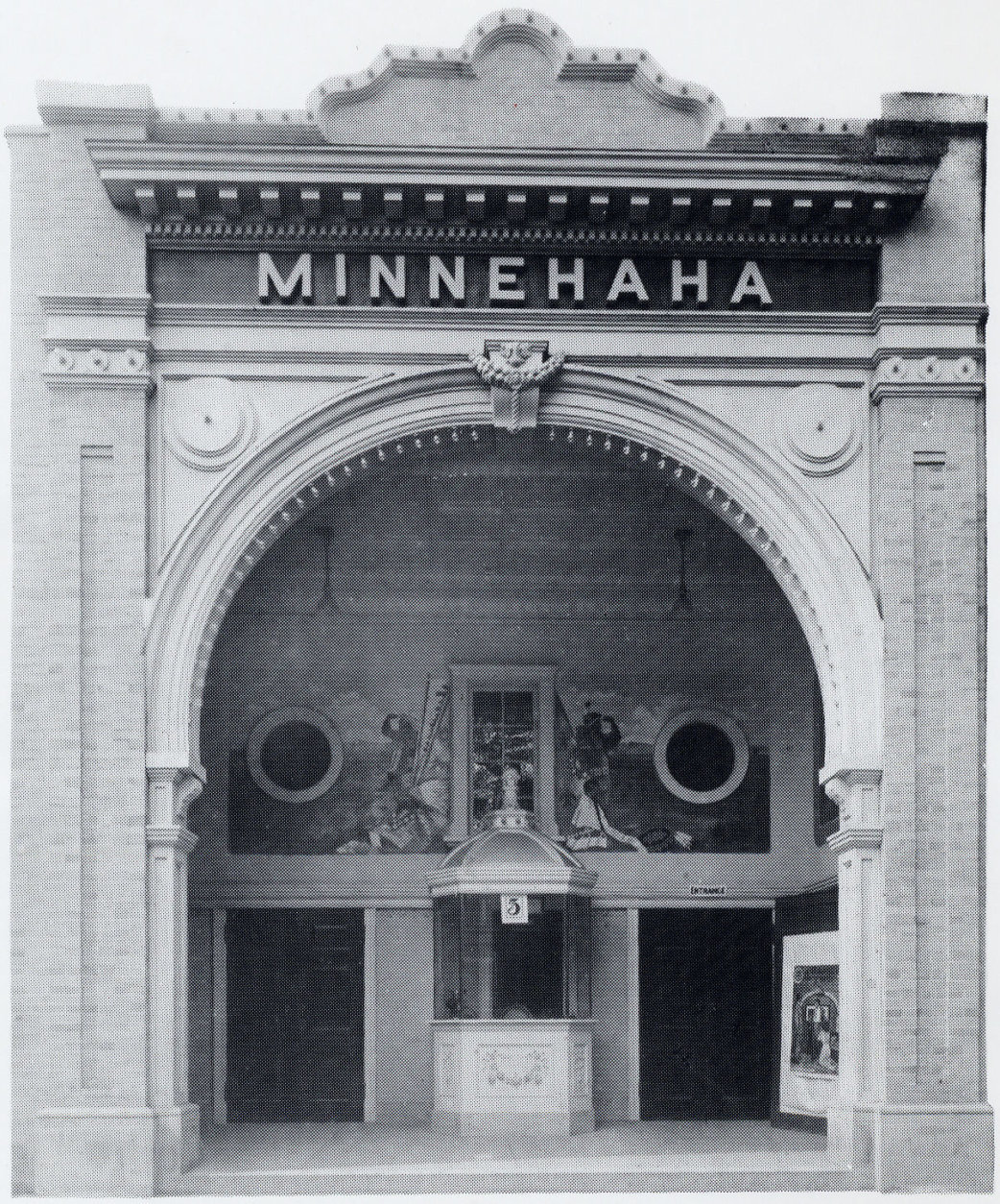

The same year they got married, he opened Ben’s Chili Bowl at 1213 U St., in a building that started as a silent movie theater and was a pool hall when they leased it.

The Alis didn’t have that many options for a location. “Back in those days, there was still a practiced segregation,” Virginia Ali told WTOP. “… This had originally been a very segregated African-American community. A very prominent one, but still a segregated one.”

That said, it was a close-knit community. “We had all kinds of businesses, and doctors, and lawyers, and plumbers, and electricians, and sanitation workers and a few winos — we had everything right here,” Ali said.

“We were able to find the architect, the contractor, the cabinetmaker, the plumber, the electrician, within six or seven blocks of here, in our own community. … And those people were with us for the duration of their careers,” she added.

Ben’s was a success right off the bat.

“There was not a good, inexpensive, quality hot dog on U Street in 1958. There were a lot of nice little cafes and soul food around the U Street corridor, but there was not a quick, easy hot dog joint,” said Bernard Demczuk, a George Washington University history professor known as the historian of Ben’s Chili Bowl. “The chili sauce … became a big hit.”

From the beginning, Ben’s was an important part of the community around it. Rhozier “Roach” Brown has been coming to Ben’s since before it was Ben’s — he patronized its pool-hall predecessor. He remembered that from the beginning, the Alis’ establishment served as a hub for what he called the “alley community” that surrounded it.

“A lot of black folks lived in alleys,” Brown said. “You see all these alleys now on Capitol Hill … these are carriage houses that they’ve renovated and, now, they’re on the market for a half-million, million dollars. But, we lived in the alley community.”

He’d come in for a hot dog — 15 cents each, two for a quarter — and the only indoor plumbing he knew.

“The Chili Bowl was our family,” said Brown, who still comes in three to four times a week. “This is my home.”

‘Soul Brother’

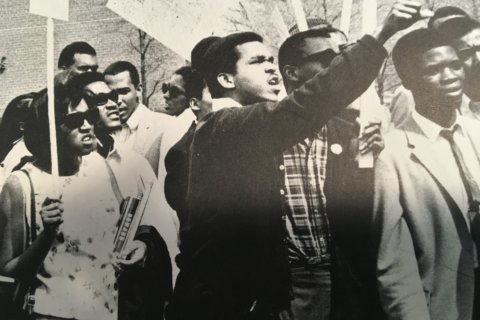

That standing in the community was particularly important during the violence that broke out in D.C., particularly in the neighborhood of Ben’s Chili Bowl, in the days following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968.

Virginia Ali remembered people running into Ben’s, claiming that King had been shot. She didn’t believe it until someone turned on the radio. Minutes later, “everybody’s in tears. … Later on, that sadness turned to frustration; frustration turned to anger, and then the uprising began.”

She recalled those violent days as “very scary,” particularly in the evenings. “There were gangs of young men … throwing Molotov cocktails, breaking into businesses, destroying property — you could see fires.”

Ben Ali put the words “Soul Brother” in the window to identify the restaurant as a black-owned business. “But many people did that, and it didn’t save so many of them,” Virginia Ali said.

Ben’s had more than words on the window: “We also had what I call an extended family by that time — a group of young men who had grown up in our community,” and included, she said, a cab driver, a plumber, a law student and a numbers runner. “And they thought every evening it was necessary to come to Ben’s and meet up.”

She points at the corner where they typically sat. “They knew everybody and everything on the street, and that also had a lot do to with our safety, I think. It was just a place that was home to so many in our community.”

King’s death, and the violence that followed, “really, literally destroyed the community,” Ali said. “It really did.”

READ MORE: WTOP’s series “DC Uprising”

- DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 riots

- How Ben’s Chili Bowl survived the 1968 riots

- An oral history of the 1968 riots

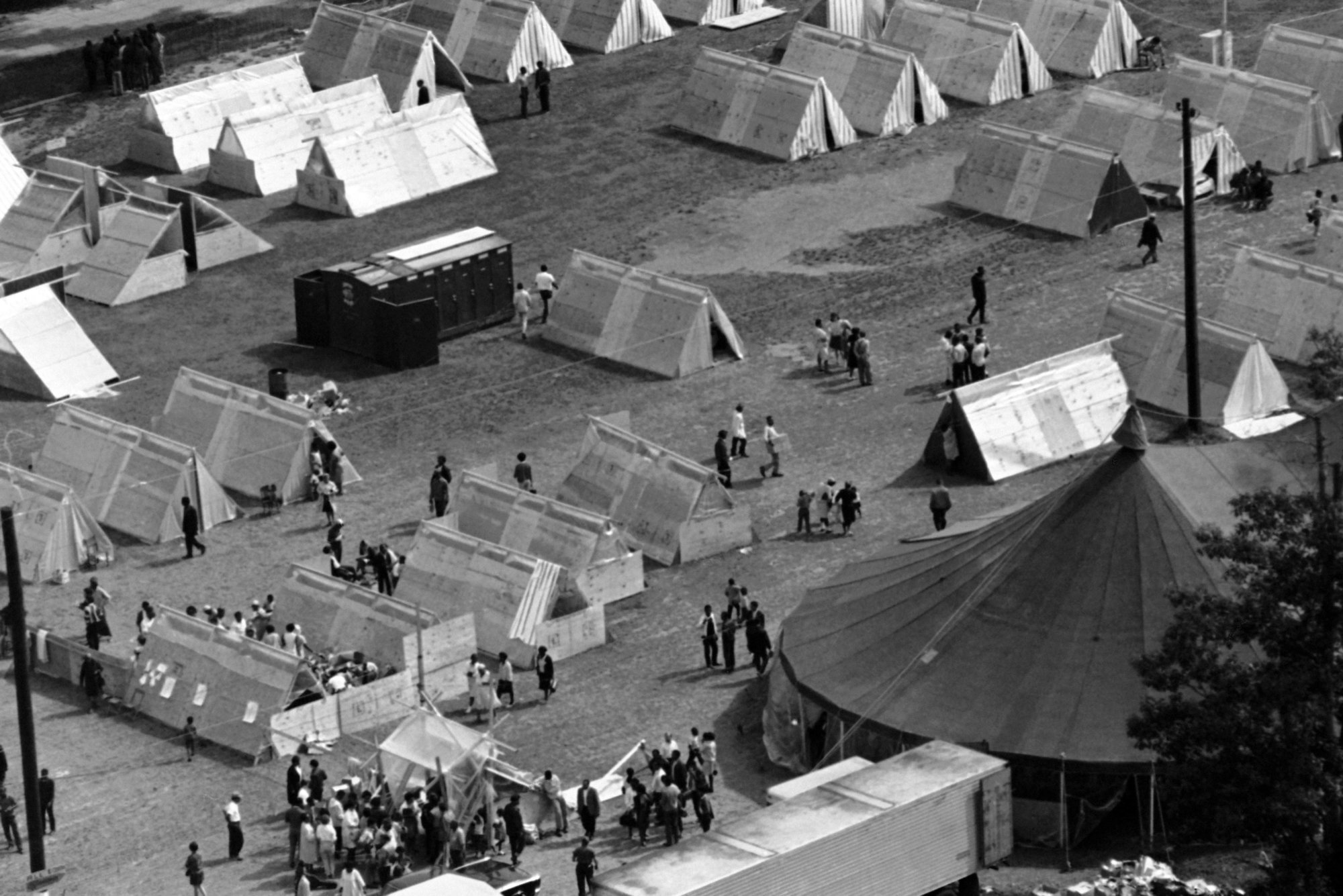

Though integration had already begun to dilute Black Broadway, the riots started what Ali called a 20-year decline in the neighborhood. “The businesses didn’t reopen after the riots. … And middle-class African-Americans began to move away.”

Demczuk said the process began well before that. By 1968, he said, the black middle class had been leaving the U Street area for about 10 years. And, after the violence, Demczuk added, “People felt fearful to come down. I came down a couple of months later … and you could still see and smell the burned-out buildings. They didn’t clean it up — that stuff just stayed there.”

As the middle class moved out, what was left was a relatively poor population, Demczuk said. And when the drugs came into the neighborhood, what followed was crime and violence. In the late 1980s and into the 1990s, the U Street corridor was “horrible,” he said.

“It was a violent place. People did not come down there,” Demczuk said.

‘We survived Metro’

Through all that, though, Virginia Ali said the only time in 60 years they seriously considered closing up was during the seemingly eternal construction process for Metro’s Green Line, particularly the nearby U Street/African-American Civil War Memorial/Cardozo station, which took from 1986 to 1991.

Ali said that at points during the construction, U Street was down to one lane. Demczuk added that customers couldn’t get to the front door of Ben’s; they had to go through the side door in the alley.

There were about three businesses left on the street: Ben’s, the bank about a block and a half away where Virginia Ali had her first job, and a flower shop across the street from that. The streetlights were turned off for much of the construction period, and Ben’s closed at sundown.

“My husband found something else to do, because he thought it just wasn’t worth it,” Ali said. “I had one employee and me. … But, we felt like, ‘This is the nation’s capital! It’s got to come back!'”

When the station finally opened, she put a banner on Ben’s that read, “We survived Metro.”

The Metro station, and the Green Line, had its intended effect, though, Ali said: Businesses came back bit by bit, and townhouses began to replace the boarded-up houses.

Today, high-end apartment buildings such as The Ellington and 2020 12th St. are bringing people back to the street. “We are a vibrant community now, and we have got people from most countries in the world,” Ali said.

“People from all walks of life,” she added. “And, I can’t wait to live long enough to see how it grows.”

‘You touch lives every day’

The brand has exploded in recent years, with Ben’s Next Door opening — well, next door, in 2008, and locations opening on H Street in Northeast; in Reston, Virginia; and at Reagan National Airport, FedEx Field and Nationals Park, all since 2012.

The Ben’s Foundation, chaired by Demczuk, donates $50,000 a year to 16 community organizations. The alley always has at least a few people taking photos of the mural. By persevering, the little hot-dog place has become an institution.

Vida Ali, a daughter-in-law to Virginia and one of many members of the Ali family who work at Ben’s, said people put the Bowl on their list of attractions to see on a trip to D.C., and tour buses of visitors and school groups pull up to the door on a regular basis.

“People see us as D.C.,” Vida Ali said. “You realize you touch lives every day.”

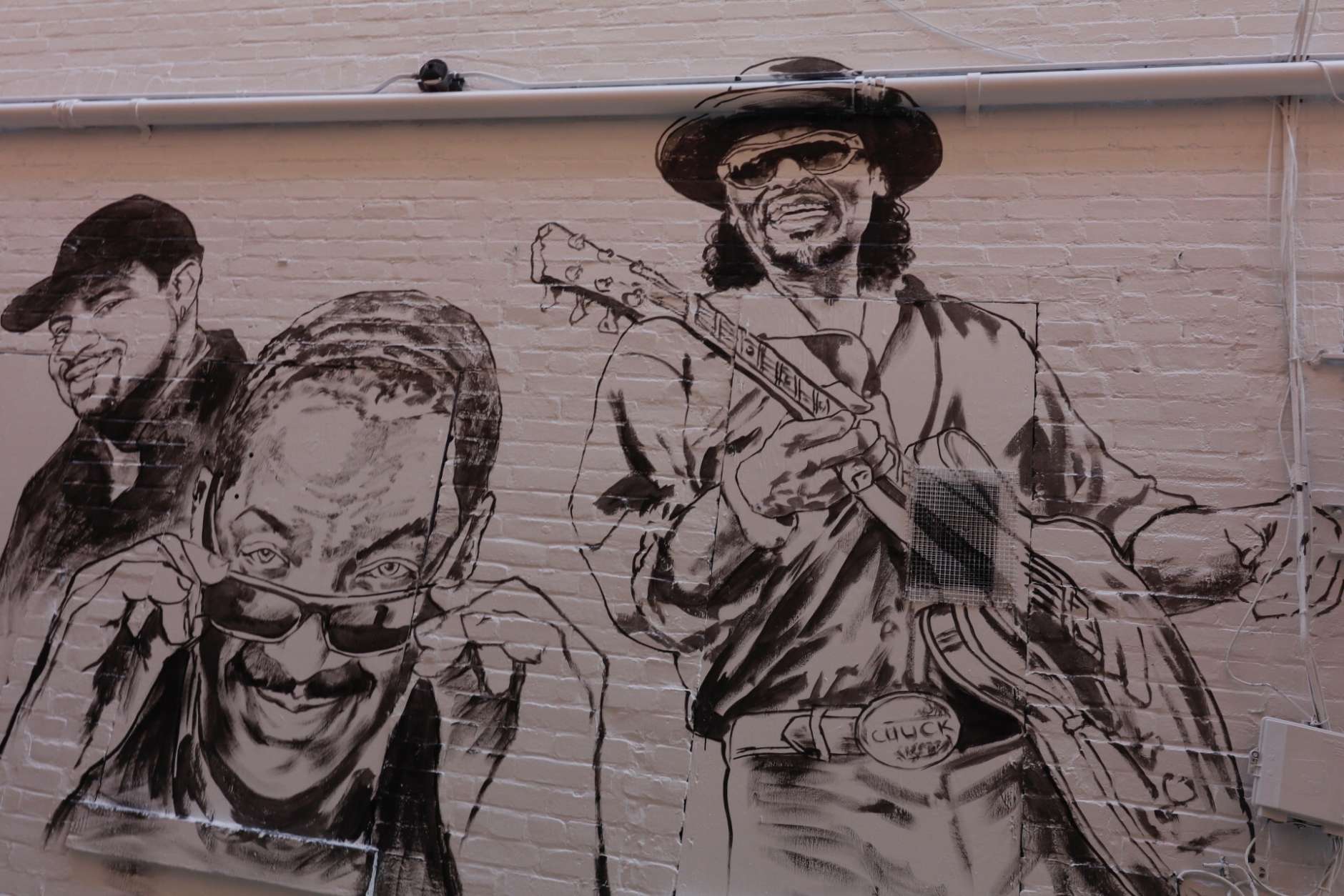

In the alley adjoining Ben’s, called Ben Ali Way, a mural depicts black historical and entertainment figures with an emphasis on locals: Dave Chappelle, Donnie Simpson, Russ Parr, Harriet Tubman, the Obamas and more.

And, just last month, when MLB brought the All-Star Game to Washington, they knew exactly where to go to paint a mural celebrating Negro League stars, including Mamie “Peanut” Johnson — across the alley from the Ben’s mural.

‘The United Nations’

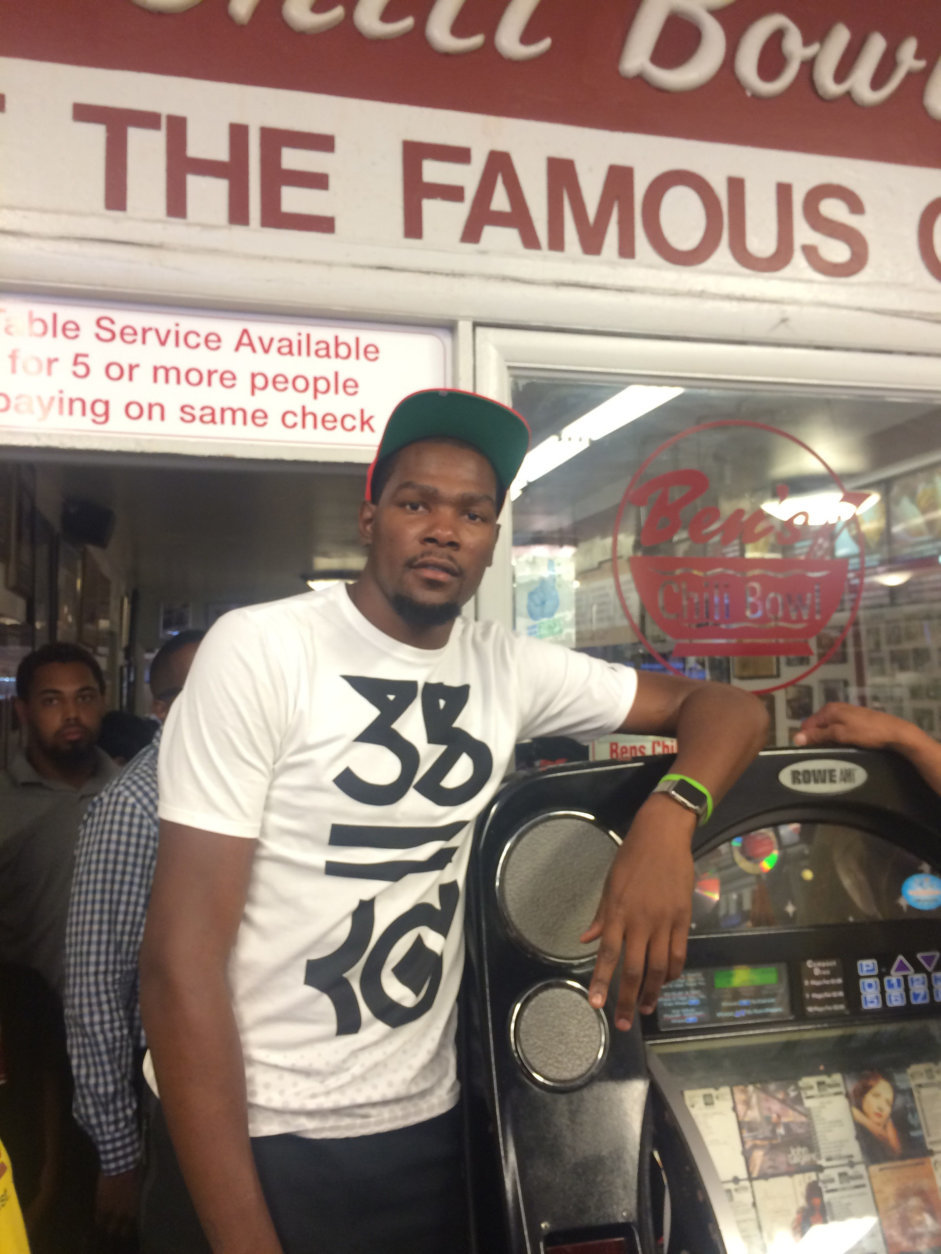

Inside Ben’s, meanwhile, a diverse collection of people meets, eats and talks much like they’ve been doing for 60 years.

Brown, who broadcasts a radio show in one of the rooms in the back, called the place “the United Nations. … You meet movers and shakers, high and low. And, everybody gets along when they come here.”

The bank and the flower shop are still there from the Black Broadway days, but Vida Ali said a restaurant is different. “There’s something social about food. It’s been a meeting place, and it’s so cool to watch all walks, all conversations — they feel comfortable having them here. That’s a true blessing.”

Virginia Ali turns 85 in December; her husband died in 2009. She never considered closing the business when he died, for the same reason that she doesn’t consider retiring today: “I get to come here every day and meet wonderful people all day long from all over the place. And, I see my children every day.” Her three sons — Sage, Nizam and Kumal — all work for the business.

She said that though she may wipe a counter once in a while, what she mainly does is talk with the people who come in. She also proclaimed herself “too busy to get sick.”

Though presidents and movie stars get the most attention from the clientele when they come into Ben’s — and are commemorated with pictures on the wall and maybe even someday a spot on the mural — Virginia Ali said, “I try to treat everyone who walks in that door as though they’re walking into my home.”

“It doesn’t matter what their status in life is; I enjoy people.”

With the 60th anniversary Wednesday, Virginia Ali said she mainly feels gratitude. “My husband and I opened this little hot dog place so that we could have a business of our own, and so we could raise a family. And yes, it is quite interesting that it’s kind of on the map. And I’m so grateful to so many people in our Washington community.”

Testimonials

Ben’s Chili Bowl is an institution, and some of the District’s most prominent people were quick to emphasize how important the restaurant is to them, to the community and to D.C.

D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser

- “Ben’s is just a fantastic establishment for our city. When people come to Washington, if they don’t know anything else, they know about Ben’s Chili Bowl, and I’m just very happy for the Ali family.”

- Her favorite: “I get a half-smoke.”

Vince Gray, D.C. Council member and former mayor

- “Virginia Ali is known and revered … I appreciate the fact that she’s still involved. …. It’s real just a part of the landscape at this point, and probably will be forever.”

- His favorite: “I get a half-smoke, maybe two, and I get the cheese fries to go with it, and the fruit punch.”

Brianne Nadeau, Ward 1 council member

- “They’ve always been concerned about hiring folks who need opportunities. Through their foundation, they support all kinds of wonderful programs. And, they’re just always available if you want to partner and do something.”

- Her favorite: “For me, it’s the veggie chili with lots of cheese. I also like the grilled cheese and the milkshake.”

Donnie Simpson, legendary D.C. DJ and wall mural enshrinee

- “Ben’s has survived it all. Through the riots, through crack, through gentrification, they’re still there and still thriving and still respected. It’s a mom-and-pop joint; it’s in the community, and everybody comes there.”

- His favorite: “I don’t eat red meat anymore, so I’m restricted to a turkey burger with cheese, lettuce, tomatoes, mustard and ketchup, French fries and a Coke. And sit me at the jukebox!”

D.C. celebrates the 60th anniversary of Ben’s Chili Bowl with a ceremony renaming the 1200 block of U Street as Ben’s Chili Bowl Way from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. Wednesday. The Ben’s Chili Bowl Foundation is putting on a birthday gala 7:30 p.m. Wednesday next door at the Lincoln Theatre.