This story is part of the WTOP series, “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.” Each day this week, we’ll tell the stories of the upheaval and tumult 50 years ago through the eyes of those who experienced it.

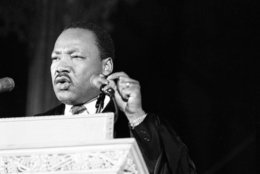

WASHINGTON — On March 31, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King stepped up to the pulpit of the Washington National Cathedral to deliver what would be his last sermon.

At the time, King had his sights set on the future. In a few weeks’ time, he told his listeners, he would be back in D.C. for one of the biggest demonstrations in the city since the March on Washington five years before.

It would be called the Poor People’s Campaign.

“Yes, we are going to bring the tired, the poor, the huddled masses,” he said, adding a few moments later: “We are not coming to tear up Washington. We are coming to demand that the government address itself to the problem of poverty.”

Planning for the Poor People’s Campaign came several months after the long, hot summer of 1967, when riots erupted in several Northern cities. Many erstwhile supporters balked. An “invasion” of activists, students and plain old poor folks would invite riots in the nation’s capital, horrified columnists wrote.

After his address, reporters asked King his prognosis for America’s inner cities. Would they burn that summer as they had in Newark and Chicago the year before?

“I don’t like to predict violence, but if nothing is done between now and June to raise ghetto hope, I feel this summer will not only be as bad, but worse than last year,” King intoned.

Four days later, King, who had traveled to Memphis to support striking sanitation workers, was gunned down by James Earl Ray as he stepped out on his motel balcony.

And in D.C. and in cities across the country, that long, hot summer ended up arriving in early spring.

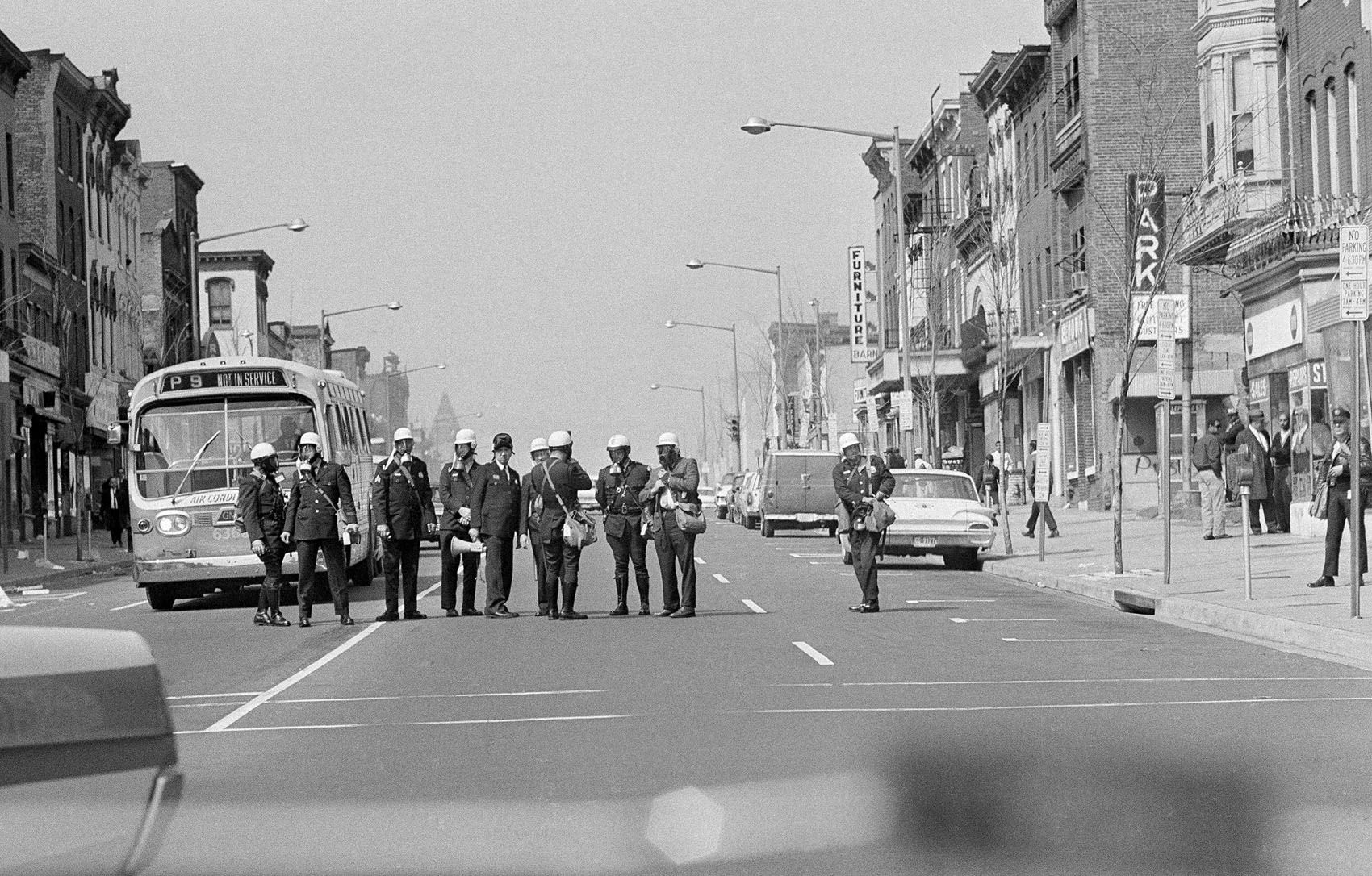

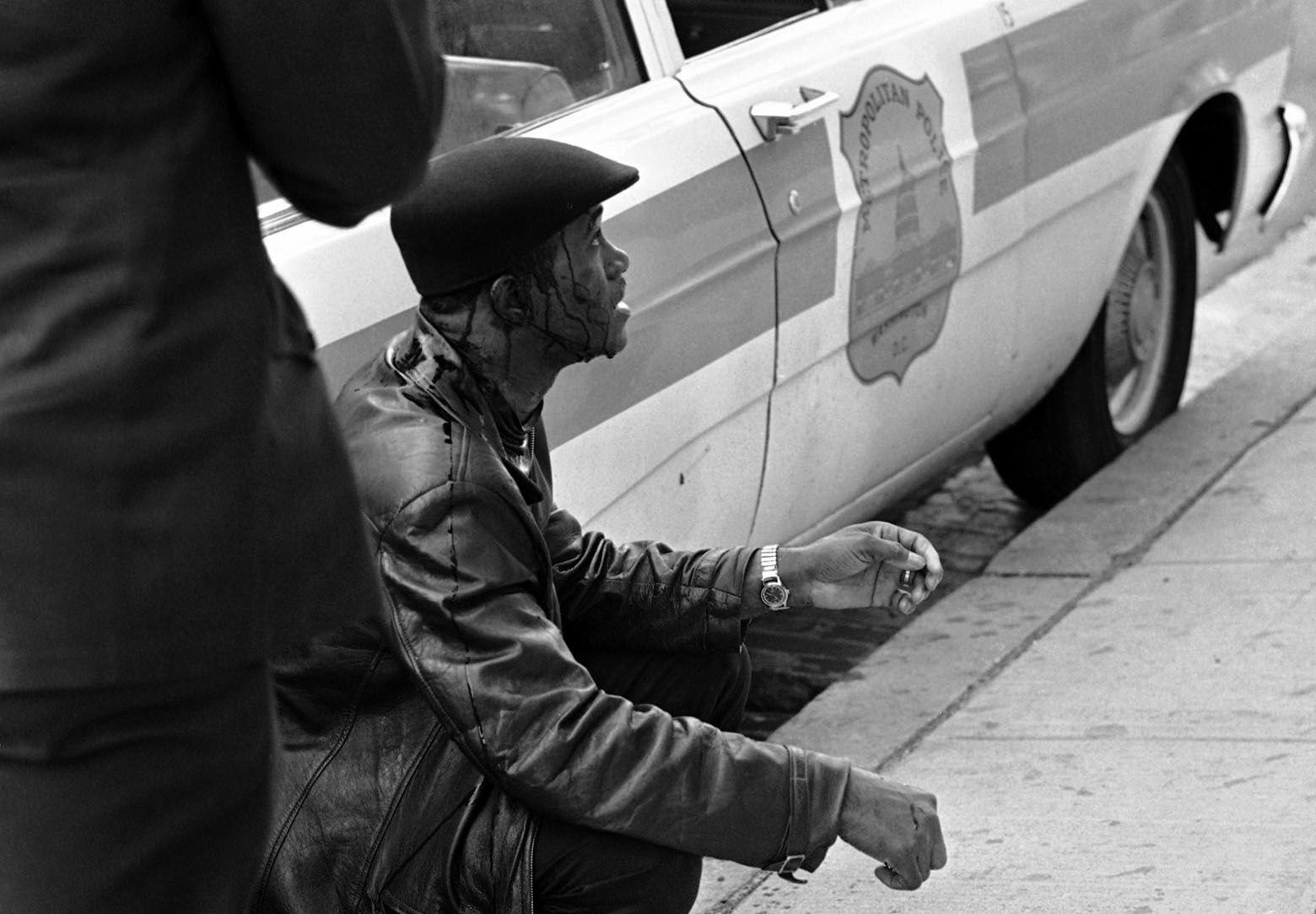

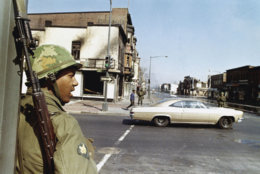

In Washington, by the time authorities had quelled the most intense disorder, more than a thousand fires had been set, more than 8,000 people had been arrested, parts of neighborhoods were ravaged, some blocks lay in ruins, and 13 people were dead, including two at the hands of police.

WTOP interviewed more than two dozen people with different experiences of the riots for our week-long series, “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.” They include retired firefighters and police officers, activists, reporters, historians and city residents who lived through the riots 50 years ago this week.

The account that follows is based on those interviews as well as archival coverage from The Washington Evening Star newspaper, the entire archives of which have been digitized by the D.C. Public Library.

Fifty years after the events of 1968, WTOP examines how the uprising shaped the Washington we know today and how the city still grapples with its legacy.

‘… She thought the world had ended’

Transistor radios and TV bulletins delivered the news that Thursday evening: Dr. King had been shot in Memphis. Stunned crowds began gathering at 14th and U streets. An hour or so later, word came that the assassin’s bullet had proved fatal.

Stokely Carmichael, the brash, visionary militant famous for coining the term “Black Power,” led an effort to get stores to close in honor of King. But the crowd grew out of his control, soon exploding into a hurricane of grief, frustration and rage.

On the evening of April 4, 1968, Manuel Rivera was 16 years old and delivering telegrams for Western Union on his bicycle.

“I had stepped in the telegraph office at 14th and Columbia Road,” Rivera recalled. “There was a white lady who was working on the teletype machine. And all of a sudden — it was dark — this guy came in, this black guy, swung the door open and shouted, ‘We’re going to kill all y’all.’ And I was a little confused because I hadn’t heard that Dr. King had been assassinated.”

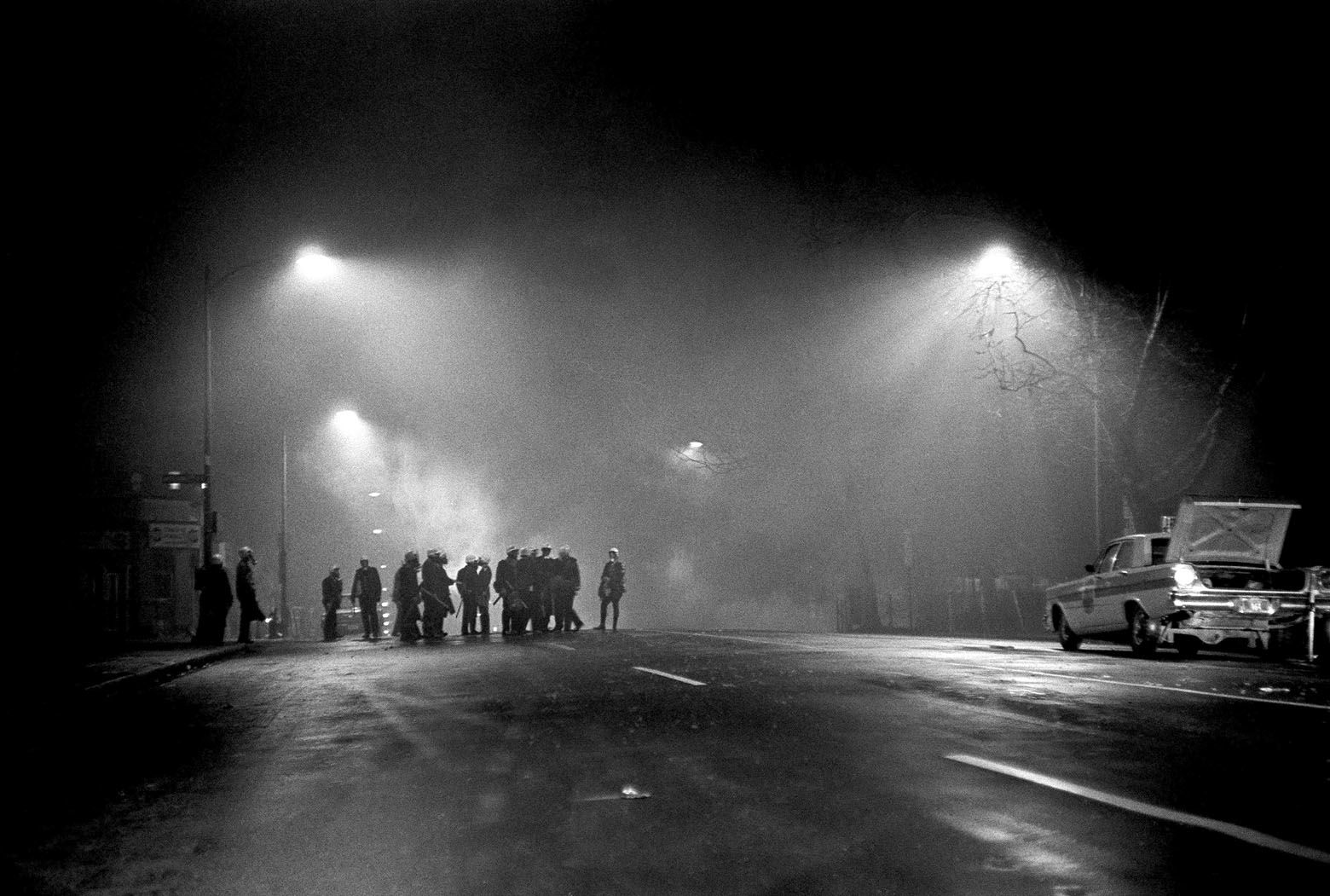

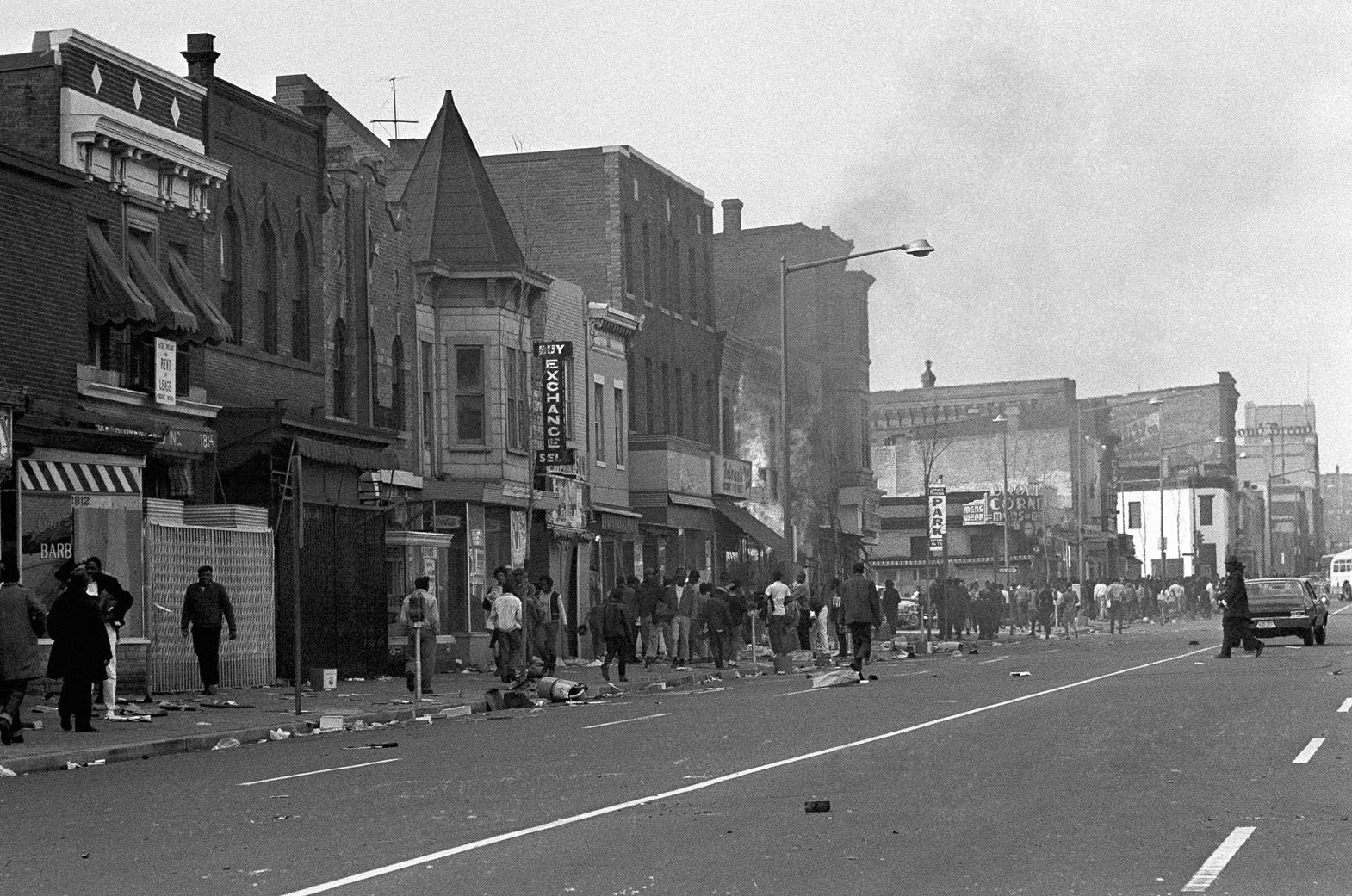

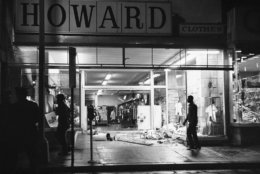

Along 14th Street, crowds began kicking in store windows, ransacking shelves and then setting stores ablaze.

Police were caught flat-footed.

“At one point, an anguished voice over the police radio pleaded, ‘Send in the National Guard, for God’s sake,’” The Washington Evening Star reported the following day.

Overwhelmed by the crowds, police weren’t able to make many arrests.

The next morning Rivera, his brother and his friends emerged from their apartment building on Girard Street in Columbia Heights.

“We could look down on 14th Street, and everything was on fire,” recalled Rivera, now 66 and retired from the D.C. police. “My mother came out and she started crying, because she thought the world had ended.”

‘Oh my God: Are we being invaded?’

Still, by dawn Friday, order had been mostly restored. City leaders thought the District would escape the turmoil other cities had been plunged into after King’s death, including Memphis and Baltimore.

Authorities had precedent on their side. In many of the previous difficult summers — in Watts and Newark and Chicago — the most intense clashes had erupted at nightfall.

D.C. would prove to be the rare daytime riot.

The fires, which had started on 14th Street, spread to Seventh Street and to H Street in Northeast Friday afternoon. Home to several department stores — a Morton’s, a McBride’s and a Sears-Roebuck — H Street was the city’s second-largest shopping district at the time.

Walter Gold was then a nightbeat reporter for The Washington Star, familiar with the seedier sides of 14th Street. (“I knew the bootleggers, the prostitutes … They accepted me, and I accepted them,” he recalled).

After the riots broke out, he was on his feet in the streets for 18 hours straight. On the second day, as black smoke choked the horizon, he recalled climbing 13th Street where it rises steeply to a hill.

“You could pretty well see all of downtown Washington,” he said. “And to see the heavy smoke coming out of those areas: 14th Street; H Street; Seventh Street. You figured, ‘Oh my God: Are we being invaded?’ … And there was some fear that this would lead to some terrible catastrophe for Washington.”

Downtown office workers who saw the clouds of smoke rising over the city panicked and clogged the streets trying to get home.

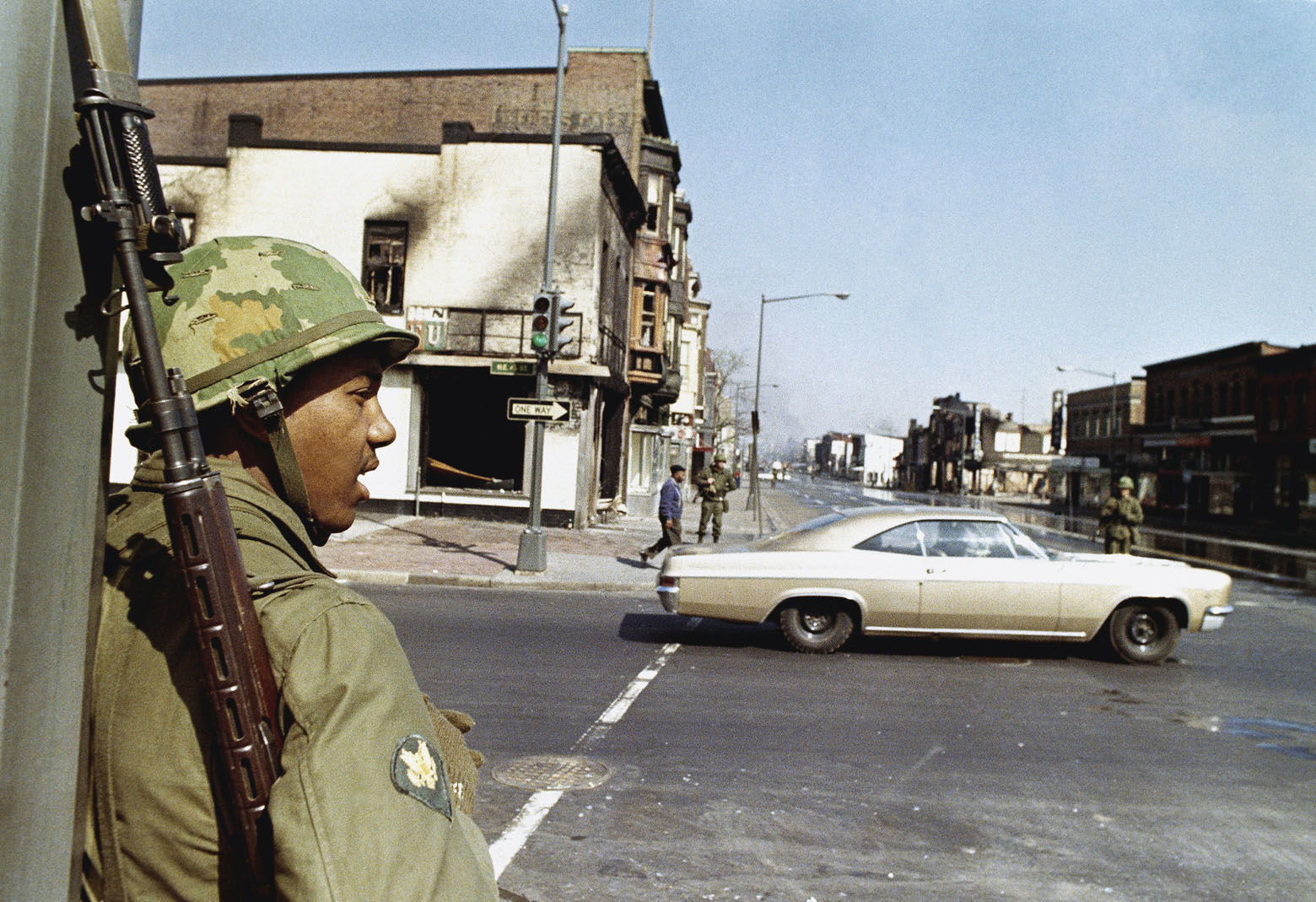

President Lyndon Johnson could reportedly smell the smoke in the Oval Office. The decision was made to call in federal troops.

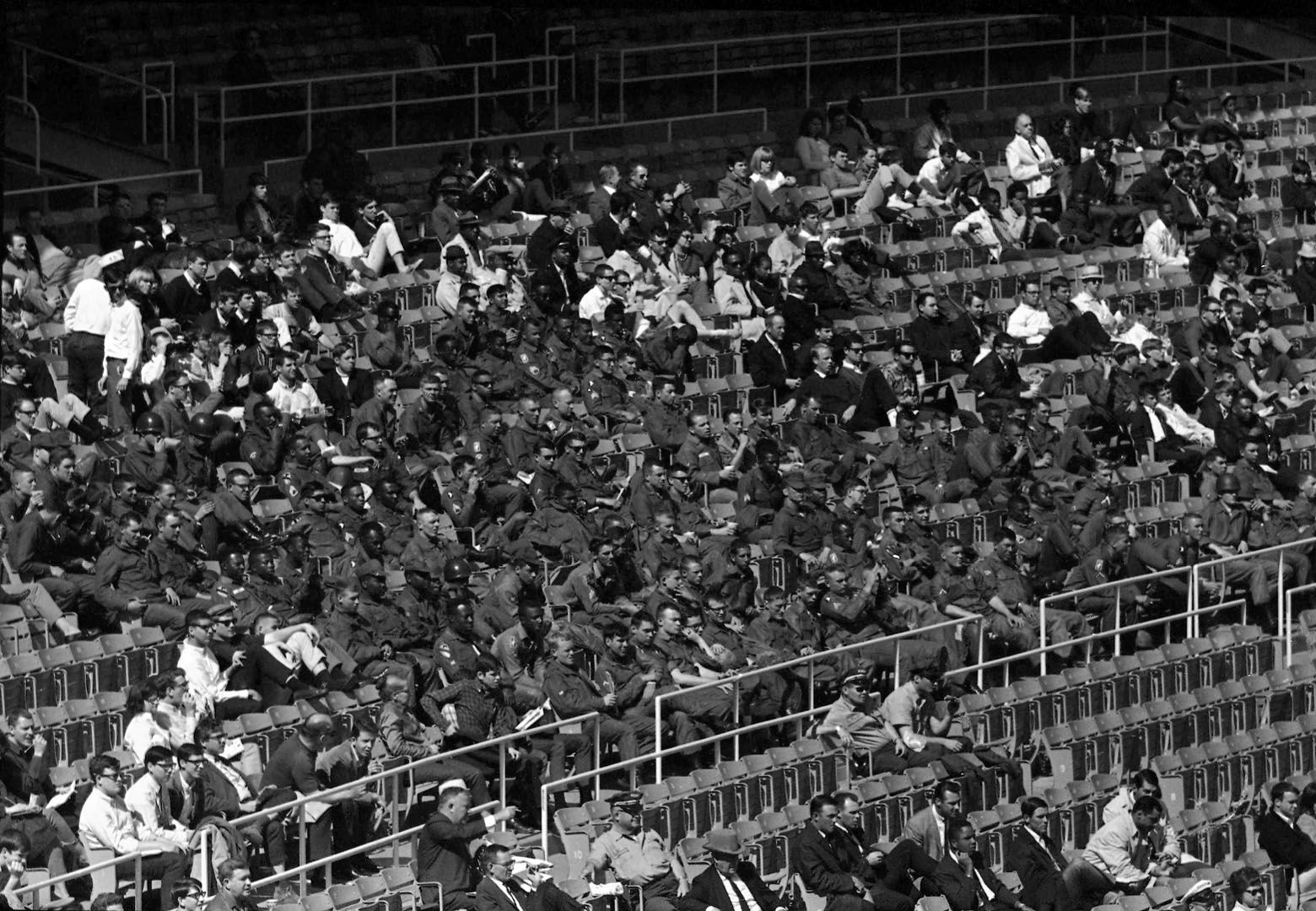

By that Sunday — Palm Sunday — more than 12,000 National Guard members and troops from the 82nd Airborne Division were either patrolling the streets or on their way to D.C. It would be the largest occupation of an American city since the Civil War, the papers reported. The troops wouldn’t roll out of town until well after the shellshocked capital celebrated Easter a week later.

‘We just went on a downhill slide for 20 years’

After the riots, crime spiked in Washington — and in most other urban centers nationwide — sparking white flight out of America’s cities, including the District.

The passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Bill — long-stalled on Capitol Hill and quickly passed in the wake of King’s murder — may have helped speed middle-class black people out of D.C., because it gave them legal redress to challenge housing discrimination in the suburbs.

D.C.’s population shrank after the riots — from more than 756,000 in 1970 to about 638,000 by 1980.

In the immediate wake of the uproar, the National Capital Planning Commission, which sent surveyors out on the streets with maps and clipboards as buildings still smoldered, estimated the damage at $13 million. That figure would later be revised to upward of several times that amount.

The rebuilding started almost immediately. But then stalled. And stalled. By Christmastime of 1968, newspaper headlines were already warning of “broken promises” in the riot areas.

Columbia Heights was likened to a ghost town. “This was once a major shopping area, dominated by large buildings, busy with pedestrians,” The Washington Post reported in December 1968. “Now it is a hollow canyon dominated by hulking burned-out shells. The street is often nearly deserted.”

Crumbling storefronts and vacant lots pockmarked the cityscape for years.

While community groups took the lead in many rebuilding projects, they were often stymied by bureaucratic red tape. Business owners were hesitant about returning. It took an act of Congress to force insurance companies to cover “inner city merchants.”

Federal policy also slowed rebuilding. The Nixon administration cut funding for subsidized housing and “urban renewal” projects, both closely associated with his predecessor’s liberal Great Society programs.

Real estate developers poured millions of dollars into D.C. in the 1980s, but it was almost all concentrated downtown amid an office building boom that saw glass-and-steel office towers rise on K Street.

“I must say that I had every belief in this city coming back,” said Virginia Ali, the co-owner of Ben’s Chili Bowl, a U Street landmark and D.C. tourist destination. Ben’s, which Ali started in 1958 with her husband, was a favored hangout for local activists, including the militant Carmichael.

After the riots, the area fell into decline.

“Businesses that were out here didn’t reopen,” Ali said. “And then the middle class moved away. And a couple years later, heroin moved in, and then crack. And we just went on a downhill slide for 20 years.”

This is the nation’s capital, she remembers thinking during those years — they’ve got to fix this. “I had no idea it would take so long,” she said.

‘It can happen again’

Today, gleaming high-rise condos and boutiques have replaced the low-slung storefronts that once stretched down 14th Street, Seventh Street and H Street. It’s perhaps ironic the three hardest-hit areas are now three of the hippest neighborhoods in D.C. The new development has brought with it thorny questions of affordable housing and gentrification.

And as the very landscape of D.C. has literally been reshaped, an entire generation of city leaders has come and gone. D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser wasn’t even alive in 1968; neither were half the current members of the D.C. Council.

The simple passage of time means the events that rocked D.C. 50 years are receding from popular memory.

“We haven’t had a lot of major riots since 1968,” said historian J. Samuel Walker, who has written a history of the D.C. uprising, published this month. “We had a large riot, of course, in Los Angeles in 1992. One in Baltimore in 2015. But there has not been the series of riots — the long, hot summers — like there were in the ’60s … Scholars and journalists and others have pondered that question. And no one knows exactly why.”

Walker’s book, “Most of 14th Street Is Gone: The Washington, DC Riots of 1968,” chronicles the roots of the unrest in Washington and how the city responded to the outbreak of violence. There are almost always once-a-decade newspaper retrospectives, but there have been few academic histories written about the riots, he said.

The history should be remembered, if for one reason only, Walker said: “It can happen again.”

The riot-scarred areas of 14th Street and Shaw have been completely redeveloped into adult urban playgrounds of bars, restaurants and condos. “But that does not mean that we’ve solved the problem of poverty and poor schools and high unemployment and substandard living conditions — substandard housing that is overpriced and overcrowded,” Walker said. “There are still lots of places like that in D.C. and we don’t hear a lot about them.”

‘A year in which people woke up’

Marya McQuirter, a public historian, has taken a different approach to remembering 1968.

McQuirter is curating the “dc1968” digital storytelling project. Every day this year, McQuirter has posted a photo and a story that provides a window into art, activism and everyday life in Washington in 1968. She also tweets the digital time capsules from her account @dc1968project.

“Part of the reason why I came up with this project is because I wanted to push back against what I call a single story or single narrative that we have about 1968 in D.C.,” she said. “If you do a browser search — ‘Washington, D.C. 1968’ — what you’ll automatically come to is April 4, April 5 — the uprising. But clearly the year, 1968, doesn’t start on April 4.”

That narrative ignores the long history of the struggle against racism in D.C. before the uprising, and also overshadows artistic and political movements that flourished in the years that followed, she said.

For example, in the six months after the riots rocked D.C., one of the first Afrocentric bookstores, the Drum and Spear, opened in Columbia Heights. The precursor to the Duke Ellington School of the Arts was founded. Crews broke ground on what would become the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Library — the only library designed by modernist master Mies van der Rohe — in downtown D.C.

And later that summer, King’s last quest, the Poor People’s Campaign, went on as planned.

The year of King’s killing should not seen solely as a “moment of rupture or fracture in this city,” McQuirter said. “I think 1968 has to be seen as a year of activism and a year in which people woke up.”

More from the series, “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.”

- ‘Everything was on fire’ — remembering the DC riots 50 years later

- DC Uprising: An oral history of the 1968 riots

- Under fire: Retired police, firefighters remember 1968 flashpoints

- ‘The mayor saw it with his own eyes’ — a reporter chronicles 1968 chaos

- After the riots, an activist on trial

- How Ben’s Chili Bowl survived the 1968 riots to become a DC landmark (VIDEO)

- Shattered lives, unanswered questions 50 years after the riots

- Small DC church survived the riots. But then came the wrecking ball. Finally, a rebirth

- Then & Now: Powerful images show 1968 riot damage and rebuilt DC neighborhoods