This story is part of the WTOP series, “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.” Each day this week, we’ll tell the stories of the upheaval and tumult 50 years ago through the eyes of those who experienced it.

WASHINGTON — Shortly before midnight on April 4, 1968, the mayor-commissioner of the District of Columbia sat in the front seat of a metallic-gray Pontiac Tempest as it sped up 14th Street.

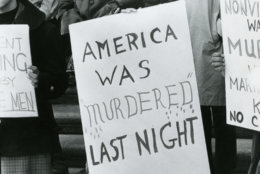

The sound of shattering glass and blaring store alarms rang out. Scattered crowds of people picked through broken store windows and emerged with clothes and radios. Groups of people on the sidewalk heckled passing cars, including the one in which the mayor sat.

Paul Delaney, a reporter for The Washington Evening Star, crouched in the backseat furiously scribbling notes as Walter E. Washington took in the damage to his city.

“The mayor saw it with his own eyes last night — eyes that were beyond tears, almost beyond blinking,” Delaney wrote in a Page One article for the next day’s paper.

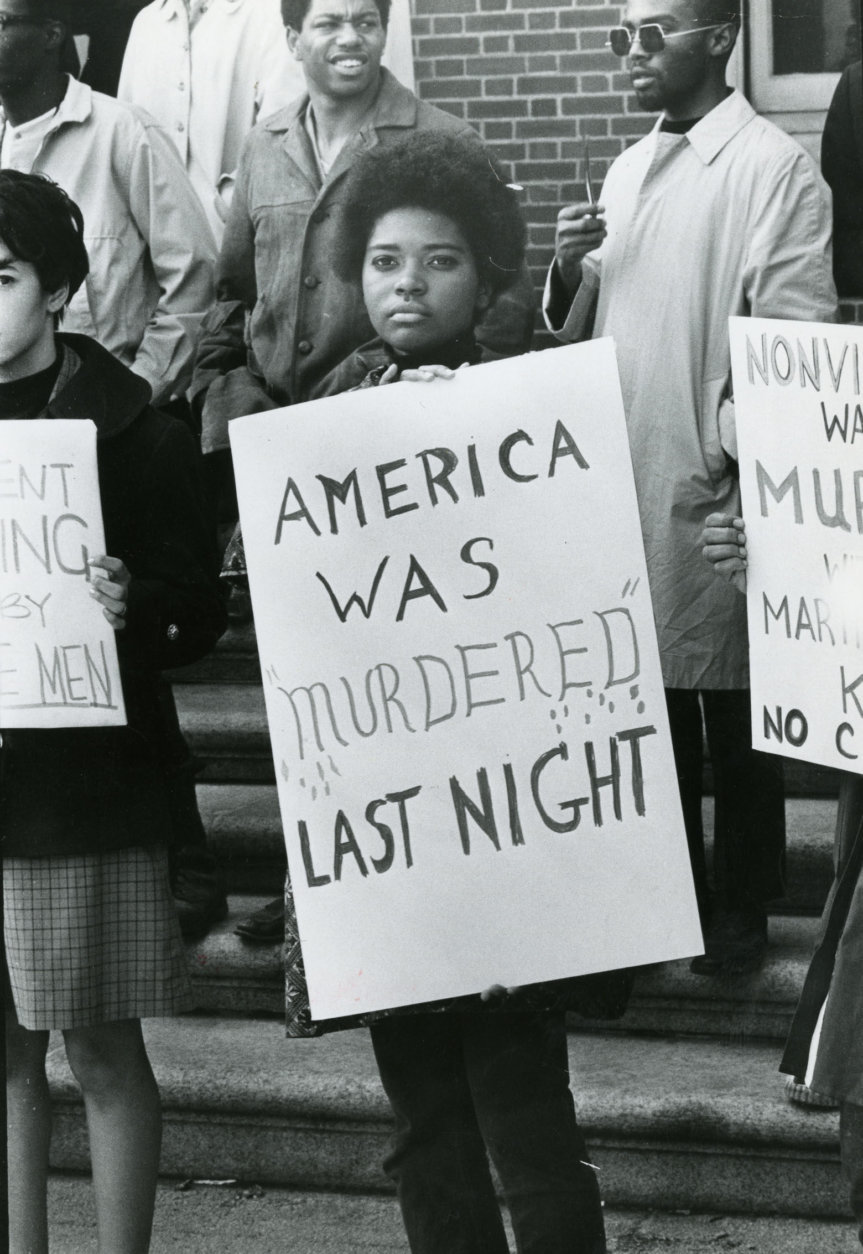

The killing of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. several hours earlier had plunged several cities across the country into chaos, and D.C. was no exception. And when the mayor decided to take a midnight tour of the damage, Delaney — one of only three black reporters on the staff of what was then the city’s leading daily newspaper — hopped in, too.

Delaney, now 85, sat down with WTOP to share his reminiscences for the series “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 riots.” This story is based on his reminiscences and on accounts from the time in his former paper.

14th and U

Earlier that Thursday evening, Delaney, a City Hall beat reporter, had filed his story for the day and headed out with colleagues to a Pennsylvania Avenue haunt, the Hawk ‘n’ Dove. They had a few post-deadline drinks and had just put in their dinner orders when the waiter came rushing back to the table: Martin Luther King had been shot in Memphis.

“We told them, cancel dinner! We jumped up and went back to the paper,” Delaney recalled.

After Delaney learned of King’s killing, he and his fellow City Hall reporter, Ron Sarro, headed right for 14th and U.

At the time, U Street was a neighborhood in transition. Before desegregation came to D.C. in the 1950s, the strip was known as “Black Broadway.” By the late 1960s, the jazz clubs and theaters were sharing space with seedy storefronts and liquor stores. Relatively new neighbors included the D.C. offices of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, as well as its younger, more militant counterpart, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

The intersection was a combination town square and red-light district.

“We knew that if there were action, it would be there,” Delaney recalled.

‘I had never felt tension like I felt here’

Delaney had come to D.C. in 1967 to cover the new city government for The Star. Earlier that year, President Lyndon Johnson had pushed a bill through Congress to appoint a “mayor-commissioner” and a nine-person city council.

Previously, the city’s nearly 800,000 citizens, a majority of whom were black, had been governed by three presidentially appointed commissioners who, in turn, answered directly to two committees on Capitol Hill. The committees kept a tight grip on the city. They ran D.C. like a plantation, many charged.

The new post of mayor went to 52-year-old Walter E. Washington, a Howard University graduate who had previously served as the city’s housing chief.

The reorganization of city government, a baby step toward home rule, came at the end of an outbreak of violence in the summer of 1967 in a handful of northern cities. The riots in Newark, Detroit and elsewhere caused millions in property damage and claimed dozens of lives — most of them black people killed at the hands of police.

Officials were desperate to keep the so-called “long, hot summer” from reaching an already simmering D.C.

And perhaps they were right to worry.

“I had never felt tension like I felt here,” Delaney recalled. “The old cliché ‘So thick you can cut it’? Well, it was. I could feel it when I first hit town.”

The city stood right on the cusp of North and South, in geography and in customs.

“When I got here, there was still a lot of segregation,” Delaney said. “That was in 1967. There were still a lot of places we couldn’t go — or wouldn’t go. It was uncomfortable. And we knew it. But it was breaking down.”

Before 1968, there had been several “mini-riots,” usually sparked by incidents of police brutality. The unrest typically died down after a few days.

“You could feel it building up to something,” he said. “And that something was the night that Dr. King was killed.”

Delaney had a personal connection to the civil rights leader. Before he came to D.C., he worked for The Atlanta World when the southern city became the epicenter of the burgeoning movement led by King.

“Everybody who was anybody in the civil rights movement came to Atlanta,” Delaney said. “And I had a chance to meet them all by being a journalist.”

The World was a black newspaper. Delaney had harbored ambitions of working at the legendary daily, the Atlanta Constitution. But at the time, there were no black reporters on staff there or at The Atlanta Journal. (The Journal would break the color barrier when it hired its first black staffer in 1968 — to cover King’s funeral.)

‘Mr. Mayor, why don’t you take a tour?’

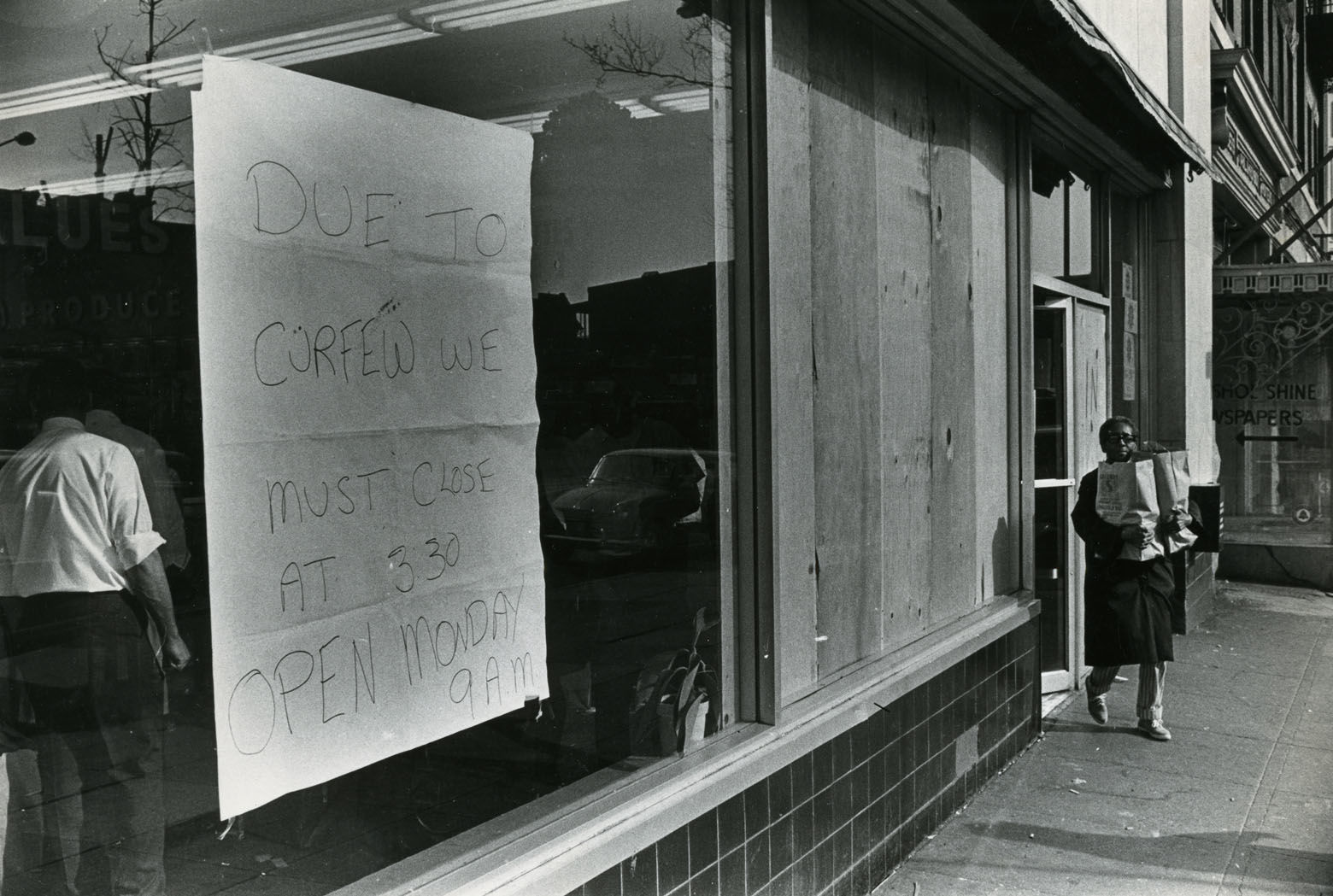

When Delaney and his partner showed up to 14th and U, a spontaneous effort to get stores to close down in honor of King had spiraled out of control. The first bricks had been lobbed through store windows. The crowds grew larger, then turned unruly.

“They would go from store to store on U Street, heading east, and we followed taking notes as windows were breaking and people were looting,” Delaney said.

That’s when the city hall reporters realized they were only a few blocks away from the mayor’s house on T Street, a three-story brick town house near LeDroit Park. They found Washington and some of his top aides just returning home. The mayor invited the reporters in as he listened to the radio and watched TV news updates.

“Mr. Mayor, why don’t you take a tour and check things out in your city?” the reporters suggested. “And sure enough he did … One of us had to go back to the paper and start writing the story,” Delaney said. “So, Ron went back to the paper. I got in the limo with the mayor.”

Throughout the drive, the mayor was mostly silent, “shaking his head in disgust and disappointment,” Delaney recalled.

But there was something else in his reaction, too. Though they were going about it in completely destructive ways, it seemed the mayor could understand the roots of their frustration, Delaney said.

In an oral history recorded shortly before his death in 2003, Washington recounted walking the streets, sometimes without a mask to protect him from the acrid clouds of tear gas, urging looters to go home.

Eventually, he would even face down FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who reportedly pressed the mayor to issue a general order allowing the police to shoot looters.

To a man who had intimidated both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington said no.

“I did pretty good in law and in political science. But no one ever taught me how to run a riot,” Washington told the oral history interviewer. “I had to learn that myself. And I did. Fast.”

Back in DC

Delaney, who didn’t stumble home until nearly 6 a.m. Friday, would learn how to cover a riot. He got a few hours of sleep and then hit the streets again to work through the weekend.

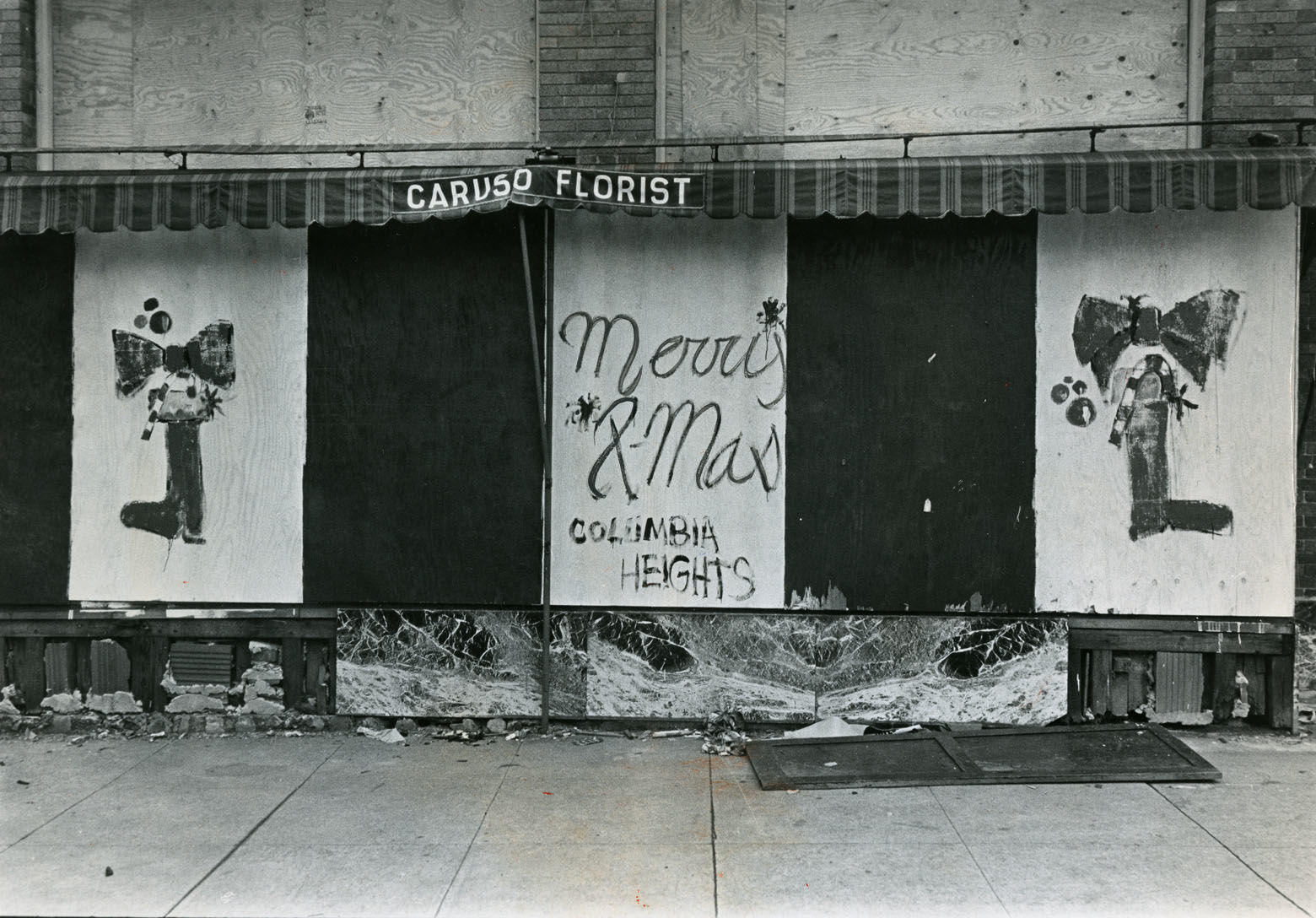

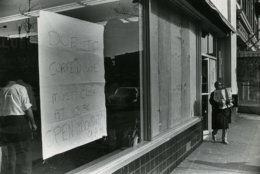

Much later, after calm was restored, the major focus of the still-new city government shifted to repairing the riot-scarred neighborhoods.

The D.C. City Council held several often-tense hearings on the root causes of the uprising and how to rebuild.

“But then things slowed down to a crawl almost,” Delaney said. “The rebuilding and the shenanigans and the conflicts and the fights started over who’s going to do what. And that went on for years.”

Delaney’s life in Washington took a turn when a new job came calling: The New York Times lured him away. He would eventually serve as the first black editor on the paper’s national news desk and would go on to help found the National Association of Black Journalists in 1975.

He retired from The Times in the 1990s after nearly 25 years with the paper. In that time, he got the chance to travel all over the world. He worked out of the Chicago bureau, then New York, then Madrid.

“But here I am: Retired and back in Washington,” Delaney said.

More from the series, “DC Uprising: Voices from the 1968 Riots.”

- ‘Everything was on fire’ — remembering the DC riots 50 years later

- DC Uprising: An oral history of the 1968 riots

- Under fire: Retired police, firefighters remember 1968 flashpoints

- ‘The mayor saw it with his own eyes’ — a reporter chronicles 1968 chaos

- After the riots, an activist on trial

- How Ben’s Chili Bowl survived the 1968 riots to become a DC landmark (VIDEO)

- Shattered lives, unanswered questions 50 years after the riots

- Small DC church survived the riots. But then came the wrecking ball. Finally, a rebirth

- Then & Now: Powerful images show 1968 riot damage and rebuilt DC neighborhoods