A half-century ago Friday, the break-in at the Democratic National Committee offices at the Watergate complex in D.C.’s Foggy Bottom led to an investigation that gripped the country for two years and led to the U.S.’ only presidential resignation. This week, WTOP’s Rick Massimo is talking with experts about how the entire affair has affected American politics, history and even the language ever since.

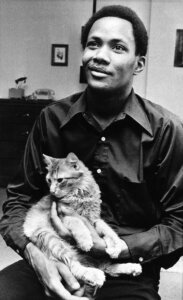

Everyone knows how the Watergate saga ends: with the resignation of President Richard Nixon in August 1974. Fewer people know much about how it began: with a security guard noticing a piece of tape on a door. And even fewer know the name of security guard Frank Wills, or what happened to him after the history was made.

“It upended Frank’s life in a way that I don’t think he ever envisioned or planned,” said Adam Henig, the author of “Watergate’s Forgotten Hero: Frank Wills, Night Watchman.”

“He didn’t have the wherewithal to handle the public spotlight,” Henig said. “He didn’t have the education; he didn’t have the family support system. And as a result, he was taken advantage of, and he made some poor decisions.”

- Watergate author on his 1973 book, meeting Nixon

- ‘Criminal mindset’ — author Garrett Graff on his new history of Watergate

- ‘Still grappling with it’ — 50 years of Watergate on film

- ‘Embracing its history’: Watergate Hotel trades on its claim to fame

- ‘Everything was amazing’ — WTOP’s Capitol Hill team on the Watergate saga

- PHOTOS: Watergate in pictures

- More Watergate Stories

A potted plant

The way the Watergate burglars were caught reads like a low farce: On the night of June 16, 1972, Frank Wills started his shift. The burglars’ lookout camped out in a room at the Howard Johnson’s that was across the street at the time, keeping an eye on the office, waiting for the last worker to leave and ready to signal the burglars hiding in the building.

That last worker was Bruce Givner, a DNC intern on his way to a career as a lawyer in Southern California. In 1972, however, he was a college student from Ohio who wanted to take advantage of the free, long distance calling in the office to talk with his friends and family.

So he did — for about two hours, while President Nixon’s burglars waited for him to leave. (Givner has written his own book on the topic.)

He didn’t leave, at one point peeing into a potted plant on the balcony because leaving the office for the bathroom would mean letting the door lock behind him.

Meanwhile, Wills had already noticed that some of the door latches on the way into the building were taped so they wouldn’t lock. He wasn’t that suspicious at first — workers often did that so they didn’t have to fumble for keys over and over — so he just took the tape off and closed the doors.

Givner finally finished his calls and went downstairs. He invited Wills to go across the street to get some food at the restaurant on the ground floor of the Howard Johnson’s. Wills took his first break of the night, locked up and headed over. While they waited for their food, the burglars went into action — and they taped the doors again.

Wills went back on duty, checked the doors again, called the police, and the rest is history.

‘People shunned him’

By the time Nixon resigned in August 1974, “Wills was an American folk hero,” Henig said.

Thing is, not everyone is cut out to be a folk hero. Henig said he spoke with Wills’ cousin, neighbors and his ex-girlfriend, who was the mother of his daughter. “This was a guy who was not a social butterfly; he was not an alpha male. He was a very insular young man who was insecure, who wasn’t a strong student …

“He grew up without a father; he grew up very poor. His mom, not surprisingly, was a maid for a white family. … His mom would do anything for him. But she had minimal means.”

Henig said several grateful members of Congress told Wills they’d happily help him become a Capitol Police officer — a real security job, with a salary and benefits. But his lack of a high school diploma, and his inability to finish a GED program, foreclosed that possibility.

Instead, Wills hired an agent who “I believe took advantage of him,” said Henig.

Between them, they founded the Frank Wills Fan Club. He was being courted for speaking engagements and autograph sessions, Henig said, “and he was hoping to parlay it into … a full-fledged career of — of something,” Henig said.

It peaked when Wills played himself in the 1976 movie adaptation of “All the President’s Men,” starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman. By then, the break-in was four years old and Nixon was two years out of office; the whole story was in the awkward space in between news and history.

Wills soon moved back to his hometown of North Augusta, South Carolina, to care for his mother in a region that went heavily for Nixon and very much did not consider him a hero.

“And he had a hard time getting jobs,” Henig said. “People shunned him.” As the years went by, “The nation moved on,” Henig said, “and unfortunately, Frank couldn’t.”

A plan to cowrite a memoir with the help of Alex Haley, of “Roots” fame, fell through. He worked for the comedian Dick Gregory and lived in the Bahamas for a time, but returned to North Augusta.

‘It’s sad to see him age’

Wills had brushes with the law; in 1983, he stole a $16 pair of tennis shoes. “It was such a minor offense, but for whatever reason, the judge wanted to set an example,” Henig said, and sentenced Wills to a year in prison.

His fame benefited him in that case: His trial was written about in Jet magazine, which drew the attention of people who got him “a lawyer of some prominence.” He was released after about three weeks, officially due to overcrowding concerns; Henig suspects officials “perhaps realized that they went overboard in his sentencing.”

Reporters would ask him for a quote on Watergate anniversaries that ended in 0 or 5, and that was about it.

“It’s sad to see him age, and to lead a very modest life,” Henig said of the footage, while “most of those who were involved in the Watergate scandal profited from this … even after they got out of jail.”

(A local example: At the time of the break-in, Wills was living in a rooming house near Dupont Circle, paying $14 a week; the house was last sold in 2010, for $850,000.)

Wills’ name made it into the histories of Watergate — sometimes. “When there was a flood of books and articles written about the scandal, they hardly would ever mention Frank by his name,” Henig said.

“It was always ‘the security guard.’ And in some cases — and this was by award-winning writers — they would call him ‘a custodian’ or ‘the Black janitor.’ I mean, they couldn’t even get his job title right. But again, that’s historically how we’ve treated people of color. It’s only been recently where we’ve finally recognized it and come to a reckoning.”

Wills died in 2000; The New York Times reported the cause of death was a brain tumor; Henig said Wills died of complications from AIDS. “This was a taboo topic,” Henig said, “even though it was running rampant within poor, rural, Southern Black communities.” Wills was 52.

“In many respects, it wasn’t a coincidence that the only Black person involved in this scandal happened to be a $2-an-hour security guard,” Henig said. “It speaks volumes about who holds political power — who gets all the breaks and who doesn’t.”

Wills got an award from the Democratic National Committee in the fall of 1974; chairman Robert Strauss said he had played “a unique role in the history of the nation.” But the story of his life, Henig said, shows that’s not what he needed.

“When you come from a family where, no matter how bad things get, you can rely on them, not only financially but emotionally — that’s the safety net,” Henig said. “Frank Wills didn’t have that.”

While casting his vote to impeach Nixon in July 1974, Rep. James Mann, of Wills’ native South Carolina, said, “If there is no accountability, another president will feel free to do as he chooses. But the next time there may be no watchman in the night.”

Henig said Wills more than once said “he regrets doing it, because of what it did to his life.” Wills’ cousin told Henig the same thing: “He said, ‘I wish this didn’t happen to Frank.’”