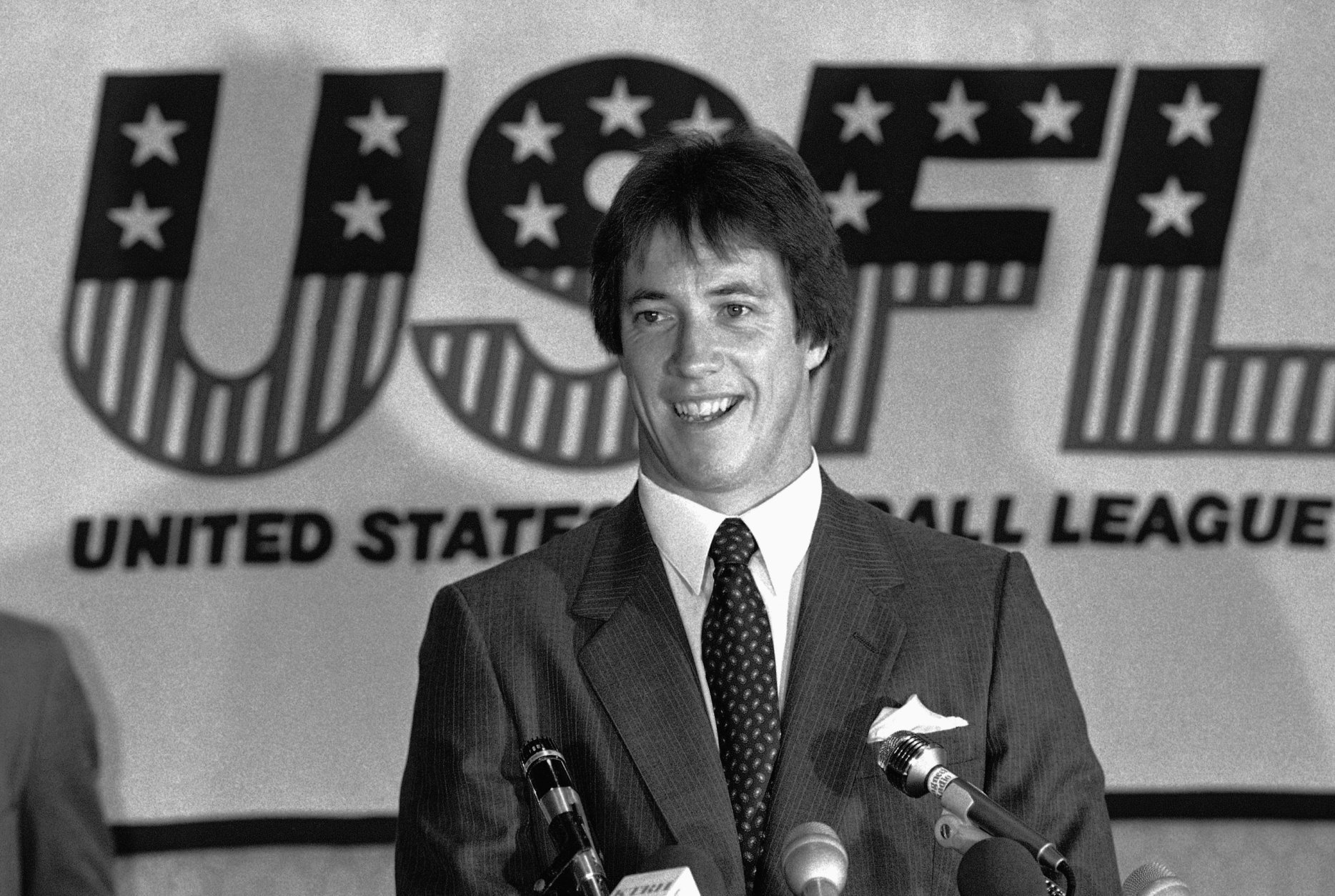

WASHINGTON — Before we begin, a disclaimer. You cannot write a book about the USFL (United States Football League) without writing about the man in the center of the league’s lawsuit against the NFL and its eventual downfall: Donald Trump. But that’s not why Jeff Pearlman published “Football for a Buck: The crazy rise and crazier demise of the USFL” now, in 2018.

This is a book he waited nearly 30 years to write. He finally got his chance several years ago, well before the last presidential election.

“I could never get a USFL book,” he told WTOP. “I would pitch it, and I’d get rejected. And I would pitch it, and I’d get rejected. I was told by my agent that nobody wants a USFL book, so I gave up on it for a while.”

In 2014, when the chance came to write a book about Brett Favre, Pearlman saw an opportunity. He actually took less money to do the Farve book, “Gunslinger,” in exchange for a two-book deal, which he used to finally write his dream book about the league he followed as a kid, and about which he wrote a 30-page high school paper … which earned him a B+.

His English teacher’s feedback on the USFL paper caused an itch he wouldn’t scratch until years later when he wrote the book: “Solid job. But I feel like there is much more to this story.”

Such as?

“I was a pretty naive kid in a pretty small town,” said Pearlman. “There was no way I knew about the drugs, the sex, the alcohol, the impact of steroids. My head would have probably exploded if you had told me these guys were smoking joints on the way to the games.”

Everything about the USFL is fantastical, and Pearlman chronicles it in a way that will bring fond memories to those who followed the league and raised eyebrows for those who don’t remember it.

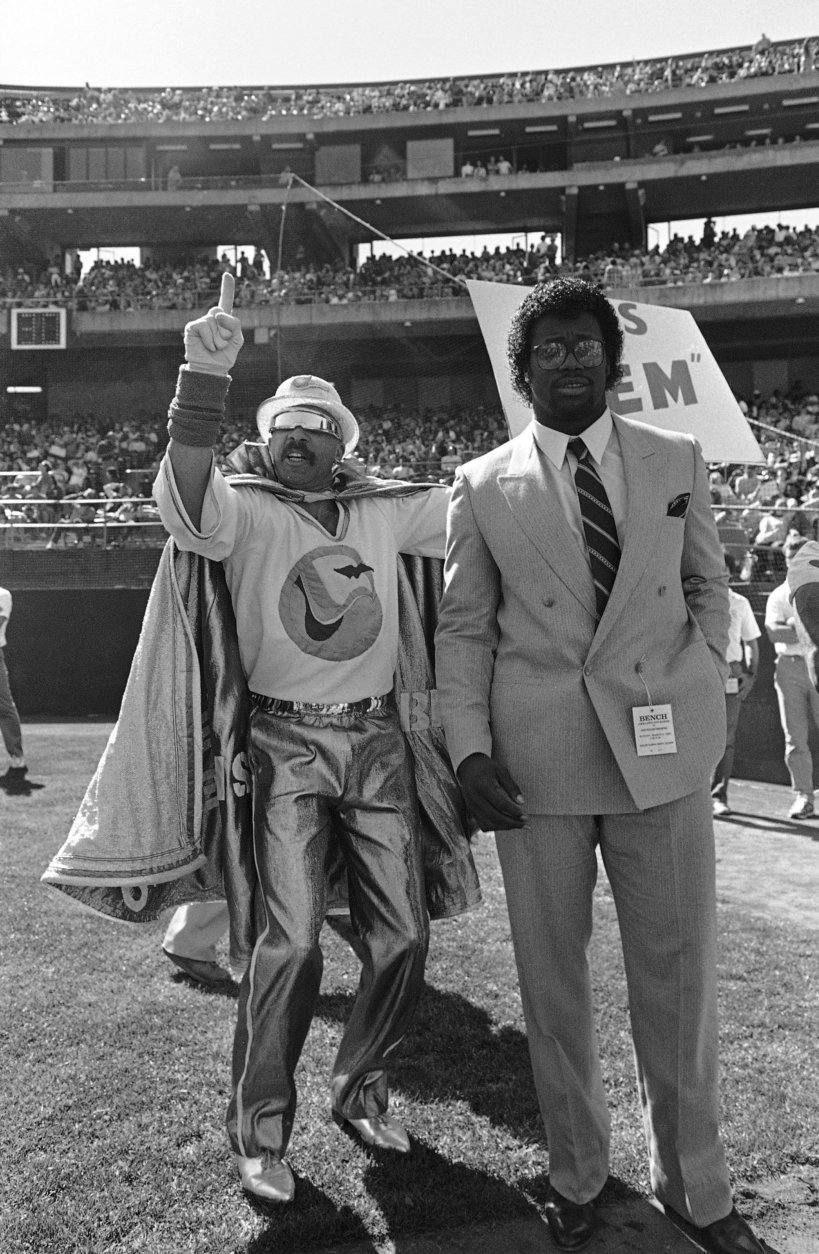

There was much more. Boston Breakers head coach Dick Coury held a weekly contest where fans designed plays for the team to run. The winner would stand on the sideline and hold headset wires that week, and at some point, the play would be put into the actual game.

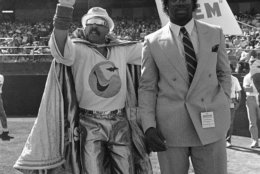

The Tampa Bay Bandits (of which Burt Reynolds was a minority owner) held a car giveaway, during which a fan sneaked onto the field and stole one of the cars, driving it right out of the stadium.

“They had a sense of humor about it, kind of like Minor League Baseball,” said Pearlman. “It was funny to them, so they would try anything.”

Much like Minor League Baseball, the USFL differentiated itself by being a league that said “yes,” rather than “no.” That also extended to on-field decisions that the more rigid and stuck-in-its-ways NFL was slow to embrace.

“The NFL has always lacked a sense of humor about itself,” said Pearlman. “It takes itself ridiculously seriously. From the uniform codes, to the penalty codes, to how the cheerleaders all have to be just the same, their hair can’t be over a certain length.”

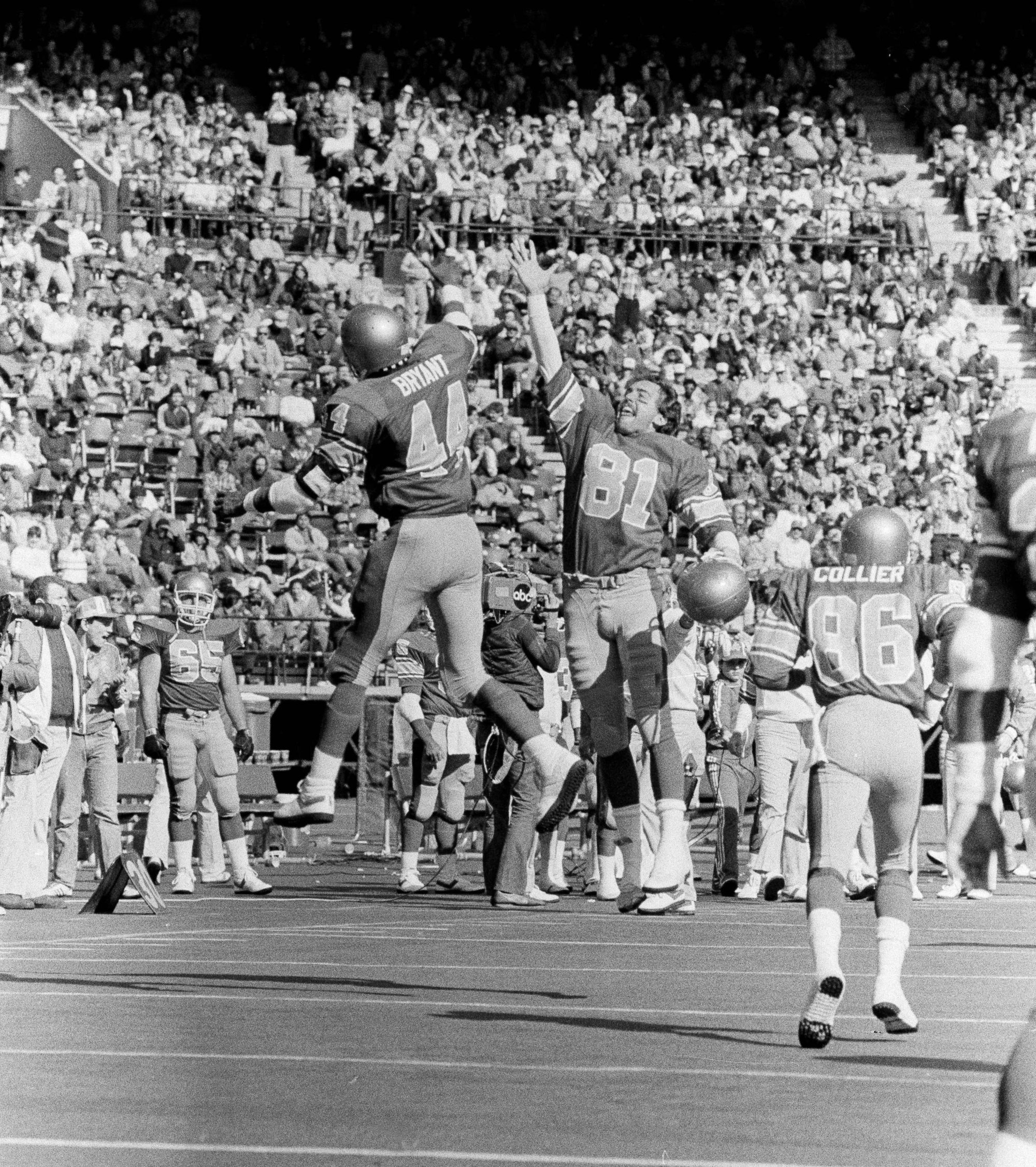

The USFL’s open-mindedness yielded everything from the successful implementation of the two-point conversion (later copied by the NFL) to the acceptance and promotion of a handful of black quarterbacks including Doug Williams, several years before he earned Super Bowl XXII MVP honors in Washington.

It also existed as a snapshot of a bygone era.

“There’s nothing more ‘80s than the USFL. Nothing,” said Pearlman. “Cocaine, big hair, embarrassingly dressed cheerleaders, alcoholic excess, unprotected sex, then protected sex because you hear Liberace had AIDS.”

And, of course, Trump.

“The proposal probably mentioned Trump,” said Pearlman. “But it certainly wasn’t like, ‘Now that Donald Trump will likely be president …’ I mean, who the hell though he was going to be president (in 2014)? That was a preposterous idea. That had nothing to do with it. It was the weirdest timing I ever had for a book.”

Pearlman said, in fact, that the only part of the book that changed in light of world events was the epilogue. Everything else was already written.

“Him being president has very little to do with the USFL, except that you can see a lot of his behavior from his USFL days,” he said.

That behavior mostly played out through the league’s fateful decision to file an antitrust suit against the NFL. Trump was the one who pushed for the league’s immediate move to the fall, despite the fact that the USFL had filled a practical void, playing in the spring, where it wasn’t competing against the more established league.

The crazy thing is, the USFL had a great case — the NFL had a television rights monopoly, through which they could apply pressure against the fledgling league, and had actually commissioned a study on how to undermine the USFL. It’s fascinating to go back and see how it all played out, and how close the league really was to potentially pulling it off, something Pearlman appreciated more now as an adult.

“The trial itself I did not know that much about,” he said. “When you’re a kid, you want to read about football — you don’t want to read about legal proceedings.”

“Football for a Buck” dives into the details of both, each of which are crazy in their own way. Pearlman’s meticulous research really shines in those moments, the anecdotes and perspectives from the inside that might have been otherwise lost to history.

“There’s a million, trillion stories that you had no clue about,” he said. “I mean, that’s the fun of it all, is digging and finding little things, the nuggets.”

Other football leagues are still trying to compete against the NFL, but the league has become such a behemoth, it’s hard to imagine any of them breaking through. The Arena Football League is still hanging around; rumors of the XFL’s return are on the horizon; and a new league, the Alliance of American Football, is set to start play the week after the Super Bowl in 2019. Pearlman’s not sure that there’s the kind of space for a league to do what the USFL did.

“It’s about the ubiquitousness of the NFL,” he said. “The NFL has made itself so it’s always there; it’s always on.”

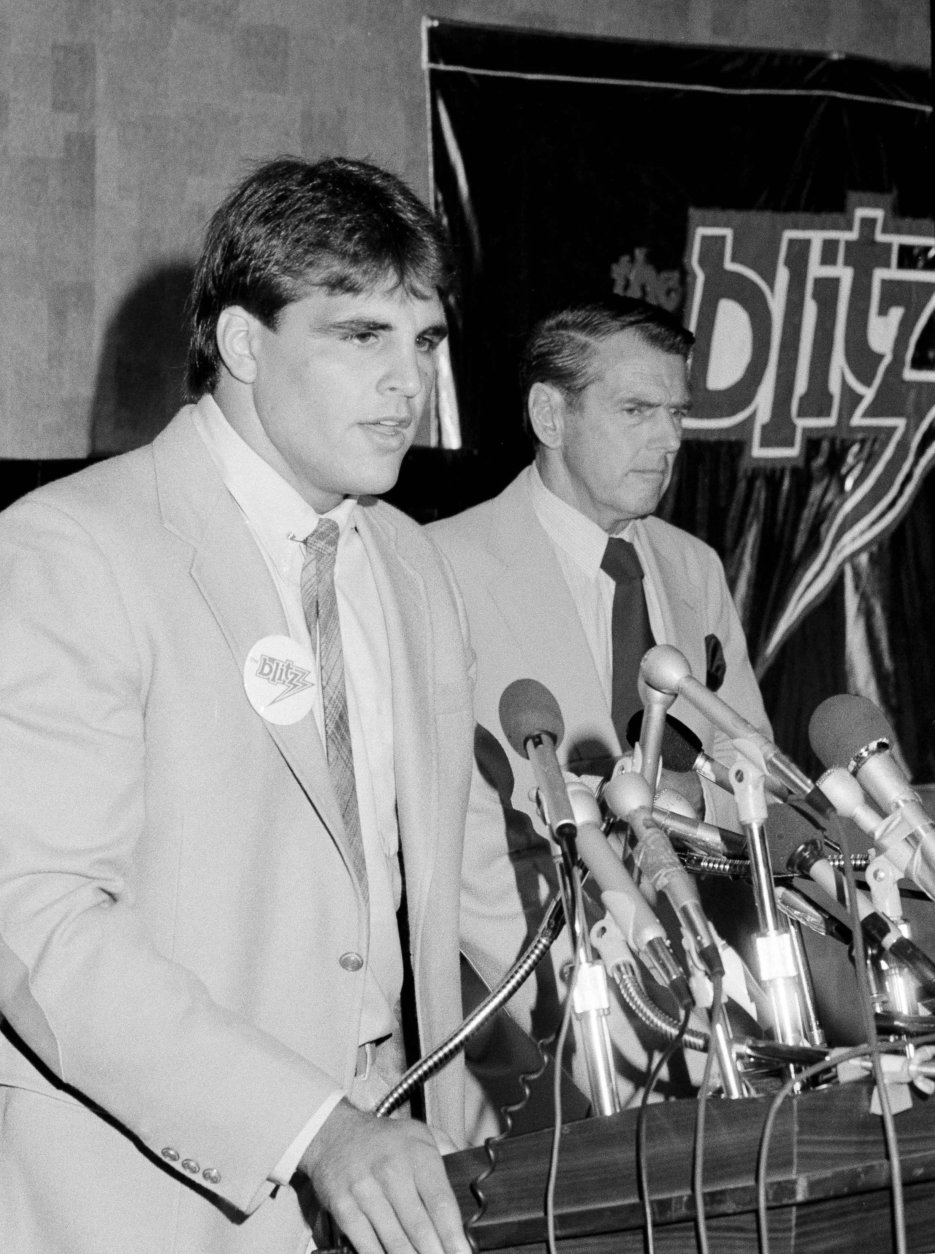

Maybe they will, at least for a few years, and maybe someday they’ll draw that same nostalgia and appeal as the USFL does to its junkies. Pearlman hosted a recent meetup via Twitter of old fans — about 15 showed up, one sporting a Chicago Blitz shirt. It’s been a fun experience for him, connecting over childhood memories with other fans who still obsess over and reminisce about the league’s freewheeling, wild three-season run.

“I’m hearing a lot from them, which is actually kind of rewarding, kind of nice,” he said.

“Because I am them. I’m that same guy.”