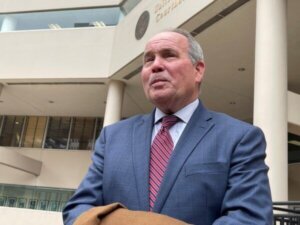

In the days before Roy McGrath’s fatal encounter with federal agents, the FBI found a way to track the fugitive, according to McGrath’s attorney.

McGrath, who was wanted for skipping a federal corruption trial in Baltimore, was on the run for three weeks. He died at a hospital Monday night after a shooting involving the FBI in a commercial parking lot on the outskirts of Knoxville, Tennessee.

The fatal confrontation remains shrouded in questions.

“I don’t have a clear indication but at some point the FBI became capable and successful in tracking him,” said Joseph Murtha, who was McGrath’s defense attorney.

Murtha said agents “recently identified a car (McGrath) purchased for himself.”

The attorney said it was the same car — possibly a white SUV shown in published photos with a broken front passenger side window — that was involved in the encounter with agents. The lawyer confirmed that several cell phones in McGrath’s possession may have also been used to ultimately pinpoint his location in Farragut, outside Knoxville.

Law enforcement agencies involved in the manhunt are so far releasing few details, citing an ongoing investigation.

“The FBI reviews every shooting incident involving an FBI special agent,” FBI Supervisory Special Agent Shayne Buchwald said in an email. “The review will carefully examine the circumstances of the shooting, and collect all relevant evidence from the scene. As the review remains ongoing, I cannot further comment at this time, only to comment Mr. McGrath was transported to the hospital last evening and succumbed to his injuries.”

Similarly, a spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney for the District of Maryland declined comment.

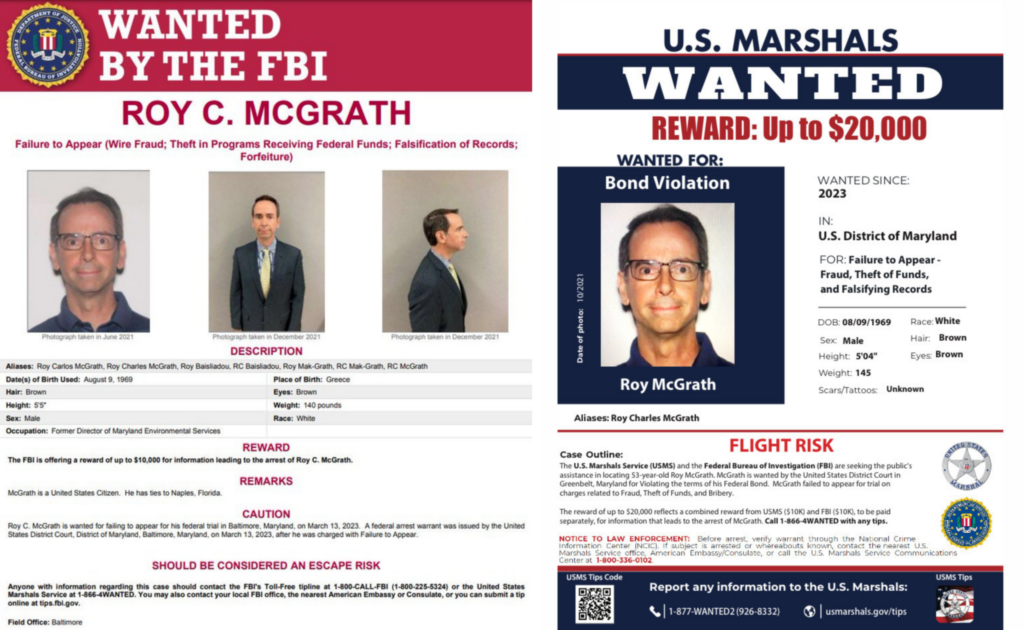

McGrath had been on the run since failing to appear for the start of his federal trial on March 13.

McGrath, who spent about three months as chief of staff to former Gov. Larry Hogan (R) in spring 2020, faced eight counts, including wire fraud, theft and falsification of a government document stemming from his steps to secure a $233,648 severance payment from the Maryland Environmental Service just as he was joining Hogan’s staff. The payment was equal to his annual salary as head of the agency.

Prosecutors alleged that McGrath inappropriately sought reimbursement for numerous expenses from the state. He also was charged with failing to claim vacation time while in Florida and on a Mediterranean cruise.

McGrath was also charged in state court. Prosecutors said he illegally recorded private conversations involving senior state officials without their permission during his employment at the Maryland Environmental Service and as chief of staff.

Murtha said the charges will eventually be dropped

McGrath had been on release, living in Florida with his wife Laura Bruner, as he awaited trial.

During his release, Murtha said his client worked as a consultant.

The terms of McGrath’s pretrial release required him to return for trial. He was also required to surrender his passport to the U.S. District Court clerk’s office in Fort Myers, Florida, near his home, in October 2021. The order barred him from acquiring a new passport. The order additionally required his wife to transfer a firearm. McGrath was ordered to undergo “medical or psychiatric treatment as required by Pretrial Services.”

On Jan. 23, the requirement for medical treatment was stricken after a request from McGrath’s attorney.

Murtha said he did not know whether his client had access to a gun at the time of his death.

Murtha became McGrath’s attorney in November 2021.

“He was always very professional and engaged,” Murtha said of trial preparations with McGrath.

“He always maintained his innocence,” said Murtha.

In the months following his indictment, McGrath set out to defend himself in public. He published op-eds in the Baltimore Sun and interviewed with the Washington Post. One of those interviews included the release of a document represented as a memo approved by Hogan, signing off on the severance package.

That memo later became the subject of an additional federal charge for fabricating documents.

“I think he was really trying to get ahead of information coming out at trial,” Murtha said.

Murtha, in interviews and in court, said he spoke with McGrath frequently in preparation for trial.

In the days before the March 13 trial date, McGrath was scheduled to be re-arraigned — a technical process to incorporate charges included in the superseding indictment.

Murtha, in a letter to the court, asked for the re-arraignment to be held on March 13. In the letter, he told U.S. District Court Judge Deborah Boardman that his client planned to travel to Baltimore on the Saturday before the trial.

Boardman granted the request and scheduled the brief hearing at 9 a.m. before a magistrate. Jury selection for the trial would begin at 9:30.

McGrath never appeared and Murtha told Boardman his client stopped responding to calls and text messages.

“He’s always been responsive,” Murtha said at the time to both Boardman and later to reporters.

Murtha told Boardman in court that he spoke to McGrath on Sunday. His client was still in Florida but was expected to fly to Maryland later in the day. He later attributed the change in plans to flight availability.

Boardman issued an arrest warrant.

In an interview, Murtha said it was then that he became concerned about his client’s welfare and a potential for self-harm.

McGrath was not found at home during a subsequent welfare check and a search by federal agents.

For much of the three weeks, McGrath was able to elude his trackers — a task force of FBI agents and U.S. Marshals.

The FBI and U.S. Marshals doubled a reward for information leading to McGrath’s capture to $20,000. The FBI also released a wanted poster containing a number of possible aliases McGrath might use.

Around the same time, an author using the name Ryan Cooper released two digital publications about McGrath. Emails from the author claimed the first 51-page issue would show how McGrath was railroaded by Hogan.

The book contained no quotes nor citations of any kind and ultimately offered little proof.

Cooper stopped responding to emails and a phone number associated with him appears to be disconnected.

Murtha, for his part, noted the speculation that Cooper and his client were the same person. He declined to answer questions about Cooper citing conversations with McGrath that are protected by attorney-client privilege.

Murtha himself never spoke to Cooper.

“No one has talked to Ryan Cooper (face-to-face),” said Murtha. “No one has Zoomed with him or talked to him in person.”

Cooper did not respond to emails requesting comment about McGrath’s death.

Cooper released a second publication — 41 pages highlighting McGrath’s time leading the environmental service — last week.

Days later, federal agents surrounded the SUV McGrath was driving.

Supervisory Deputy U.S. Marshal Albert Maresca Jr. said “an agent involved shooting” involving McGrath that occurred around 6:30 p.m. Monday is under review.

“During the arrest the subject, Roy McGrath, sustained injury and was transported to the hospital,” Maresca said in a statement.

Later that evening, McGrath succumbed to his injuries.