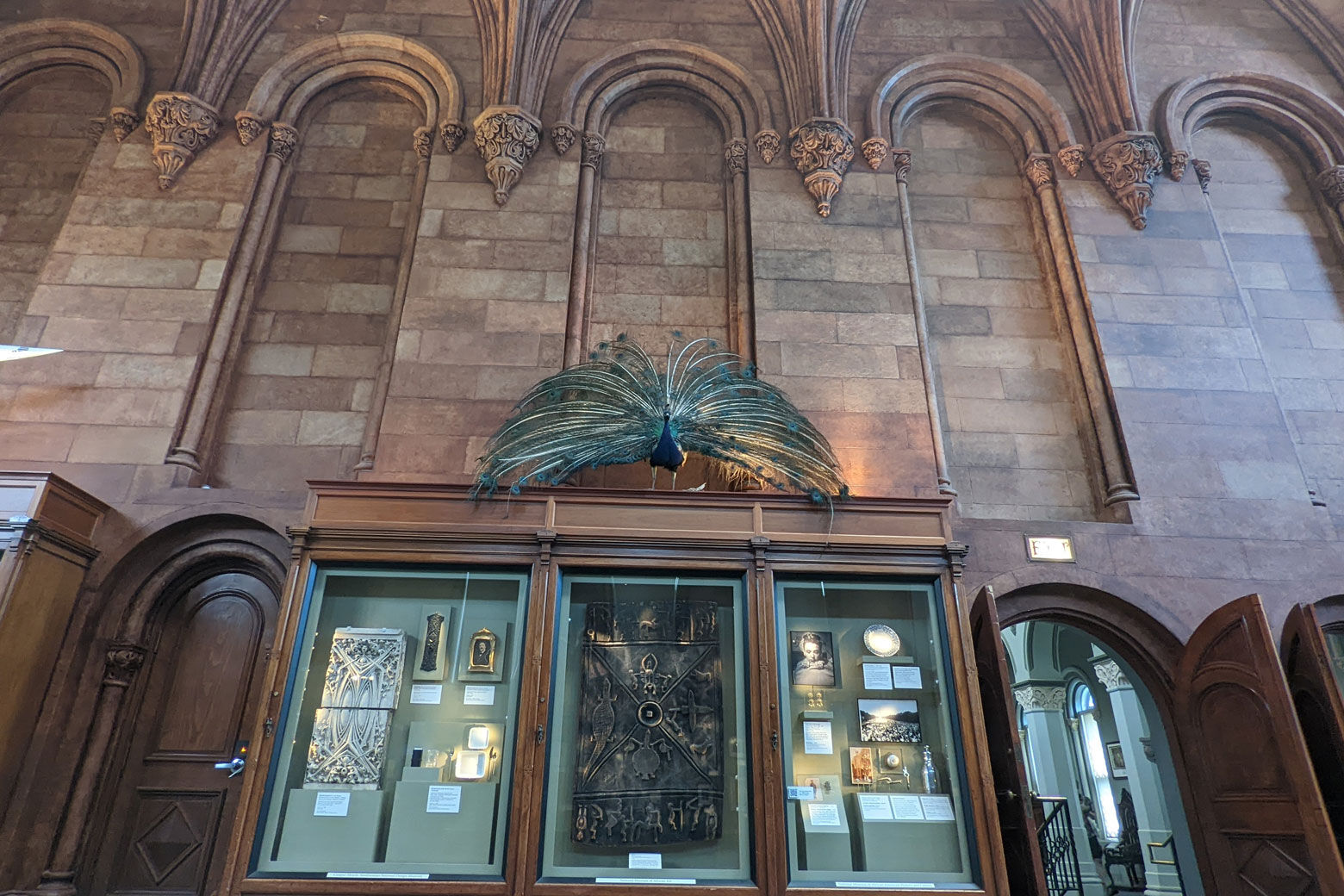

When you walk through the building on D.C.’s National Mall commonly known as the Smithsonian Castle, you can check out a variety of the museum’s holdings, from trilobites to a panda cam to an electric guitar.

Among the displays is an exhibit on the founding of the Smithsonian Institution itself, which turns 176 years old this Wednesday.

That exhibit includes a list of turning points in the institution’s prehistory; if any of them had gone the other way, the Smithsonian wouldn’t exist. It’s quite a list.

“The Smithsonian comes into being with the Smithsonian Act of 1846,” Anne Marie Gilliland, castle volunteer coordinator at the Smithsonian, told WTOP. “To get there sort of took a little bit of effort.”

It took a little more than that.

The money that founded the Smithsonian came from a British aristocrat named James Smithson. His crypt is in the Smithsonian’s main building, known as the Castle, but during his life, he never set foot in the U.S.

This video is no longer available.

Smithson was a scientist, “or a natural philosopher, as he would have called himself,” Gilliland said. The illegitimate son — “the natural-born son,” Gilliland termed him of the first Duke of Northumberland and the duke’s wife’s cousin, Elizabeth Hungerford Keate Macie.

Smithson was born in Paris and used Macie as his last name early in life. He returned to England as a child, went to Pembroke and Oxford and became the youngest member of the scientific group the British Royal Society.

According to Gilliland, Smithson was a distinguished scientist and accumulated a decent amount of money in his life. He never married or had children, and died in 1829.

Smithson left his money to his nephew, with the stipulation that if the nephew died without any children “whether they’re legitimate or illegitimate,” Gilliland said. He specified the money would then go “to the United States of America, to found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an Establishment for the increase & diffusion of knowledge among men.”

That’s exactly what happened — which is pretty remarkable, since Smithson’s nephew was only 26 at the time of Smithson’s death and died only six years later.

Why did Smithson do this? It’s not all that clear. Smithson donated his papers as well as the money, but most of that burned in a fire at the Castle in 1865, 10 years after it opened.

“We don’t have a document saying, ‘This is why I did this,’” Gilliland said.

Her best guess: Because of the circumstances of his parentage, Smithson couldn’t take his place in British society through the usual means, such as joining the military or becoming a church leader. He and his father knew each other, but his father “never acknowledged him in any sort of public way … he wasn’t acknowledged in society.”

Gilliland theorized, “perhaps he leaves his money to the United States because it’s … this new society that’s free of the aristocratic constraints that he bumped up against all of his life.”

More money, more problems

So, all’s well that ends well. We get the money and we open a museum. Story over, right? Not quite.

After Smithson’s nephew died, it took another two years to actually get the money from the courts in England, which was actually record time; we were roughly 800th in line at the Court of the Chancery, and some of the cases before the Americans’ were ultimately never resolved.

Once the money arrived, though, there were still plenty of hassles on this side of the pond, leading to “about a decade of hemming and hawing” before the Smithsonian was established, Gilliland said.

For one thing, Smithson was, you know, British. Not only were they American opponents in the Revolutionary War, but also during the rematch in the War of 1812, which featured the burning down of the White House.

“And so, there was suspicion in accepting money from somebody from that country,” Gilliland said. “And also, there was nothing in the Constitution saying, ‘Yeah, take money from this foreign guy who wants to put a building right in the middle of your brand new national capital, with his name on it.’ That’s very presumptuous on his part.”

The Castle is pretty presumptuous itself: a red stone James Renwick-designed building “meant to look like a European university … versus the Greco-Roman architecture of all of our federal buildings,” Gilliland said.

It includes nine towers, no two of which are alike. It was finished before the present Capitol or the Washington Monument, which makes for an intriguing visual.

What does it look like?

One question arose immediately: What does “an institution for the increase and diffusion of knowledge” mean? It seems obvious now, but it wasn’t at the time. “Is that a college?,” Gilliland said. “Is that a library? Is that a museum? Or is it a research center?”

The first secretary of the Smithsonian, Joseph Henry (the subject of the only stand-alone statue on the Mall), “thinks we should just be researching and publishing our research and sending that out into the world,” Gilliland said. “He just wanted two rooms to do publishing.”

His other objection was that a museum would be strictly a local attraction: “How are you going to increase and diffuse knowledge across the world if it’s these museums that are just in D.C.?,” Gilliland said.

That’s a pretty good point, given that D.C. at the time was mostly rural — not exactly a tourist hot spot. For that matter, the concept of tourism as we know it today didn’t really exist, either.

“But there’s value in making those museums as well,” Gilliland said, and Henry’s assistant and successor, Spencer Fullerton Baird, certainly thought so.

He was a scientific collector, and as the nation expanded westward, he attached scientists to expeditions that were surveying and documenting the land, “and they send back specimens. And that’s where we’re starting to get the collections that people are so familiar with.”

Soon afterward, in 1879, came the Arts and Industries Building, next door to the castle. The natural history museum and National Zoo open around 1910, and the Smithsonian eventually expanded to its current 21 museums, becoming, in Gilliland’s words, “the largest museum and research complex in the world.”

When the pandemic shut down so many cultural institutions, including the Smithsonian, they carried on with an expansion of their virtual offerings. In a way, they fulfilled Henry’s worldwide vision by doing that.

“I think he would have been delighted and just totally fascinated by all of this,” Gilliland said. “We were able to reach new audiences across the world in ways that we previously were. And that’s just continuing to grow and expand. And it’s really exciting.”

Smithson died in Italy and was buried there. In 1901, when the cemetery was about to be moved, the inventor Alexander Graham Bell, a regent of the Smithsonian who had been mentored by Joseph Henry, argued for bringing Smithson’s body to the Castle.

After a few more years of familiar-sounding wrangling and design changes, his remains lie in a small, simple room off the entryway, while thousands of people a day walk past, into the Castle and the Smithsonian Institution’s 21 museums, increasing their knowledge and diffusing it in their hometowns all over the world.