A half-century ago Friday, the break-in at the Democratic National Committee offices at the Watergate complex in Foggy Bottom led to an investigation that gripped the country for two years and led to the U.S.’ only presidential resignation. This week, WTOP’s Rick Massimo is talking with experts about how the entire affair has affected American politics, history and even the language ever since.

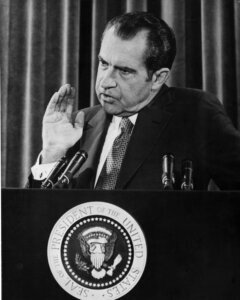

While June 17 is the 50th anniversary of the break-in, those who saw the scandal that ended Richard Nixon’s presidency unfold at the time remember Watergate as more than a single event. And the author of the newest history of the scandal calls Watergate “less an event and more a mindset.”

Garrett Graff, a former editor at the Washingtonian and Politico and the author of “Watergate: A New History,” told WTOP that the burglary “was really only one piece of that story, and the full tale of Watergate encompasses about a dozen distinct and interrelated scandals with overlapping players and differing motives that unfolds from the ‘68 campaign, right through Nixon’s final days in the summer of ‘74.”

In Graff’s analysis, the “original sin” of the Nixon presidency was the Chennault Affair, revealed only in recent years: The secret communication between the Nixon campaign and the South Vietnamese government, in which Nixon and his camp told the South Vietnamese to delay the opening of peace talks, saying that South Vietnam would get a better deal after the 1968 election if Nixon won.

From that kind of start, Nixon spent his presidency looking over his shoulder. The release of the Pentagon Papers, in 1971, didn’t implicate him in the years of lies told by the U.S. government about the Vietnam War, but the fact that they got out made him paranoid about leaks.

That led him to set up The Plumbers, a secret counterintelligence operation in the White House focused on capping the flow of information (plugging leaks, you see) and of punishing enemies. From there came the “dirty tricks” and the — well, it’s not a printable word, but let’s just say it describes how rats make new rats — that led to the break-in at the Watergate Hotel.

“Watergate, as we have come to understand it,” Graff said, “was less an event and more a mindset. … It was this dark, paranoid, conspiratorial, criminal mindset that permeated Richard Nixon’s presidency and his administration in the White House from 1968 right to 1974.”

Graff said he wrote the book because, after covering the Trump administration, “that got me interested in the last time our country confronted a series of questions about crime and criminality and corruption in the presidency.”

As much as Watergate has continued to resonate through American culture and politics, there hasn’t been a full-on, book-length history since Fred Emery’s “Watergate: The Corruption of American Politics and the Fall of Richard Nixon” in 1994.

A lot has been revealed since then — perhaps most notably the identity of Deep Throat, one of the key sources of information for Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. And the revelation of the source as FBI Deputy Director Mark Felt — who denied it, as did Woodward and Bernstein themselves — changed a lot of perceptions.

“We had this idea of Deep Throat, handed down from the movie ‘All the President’s Men,’ of Hal Holbrook standing in the parking garage and telling Woodward to follow the money,” Graff said (a phase, by the way, the real Deep Throat never actually said). “And [we] imagined Deep Throat as this, pro-democracy, truth-justice-and-the-American-way Nixon insider trying to fight the worst abuses and corruption of the Nixon administration.

“And what we now understand is that that’s not what Deep Throat was up to at all.”

Felt, in fact, was “a bitter bureaucrat upset that he had been passed over to become the director of the FBI in the wake of the death of J. Edgar Hoover. And that he was out there trying to really engage in some pretty run-of-the-mill backstabbing, bureaucratic office succession politics.”

‘The cover-up is worse than the crime’

That’s not the only myth that Graff’s research turned up. The phrase “the cover-up is worse than the crime” entered the American lexicon during Watergate, and has become conventional wisdom ever since. “But when you go back and you look at Watergate,” Graff said, “that actually turns out not to be true at all. The crimes of Watergate were many, and myriad, and together encompass some of the worst abuses of power and of the civil liberties of ordinary Americans that we have ever seen a president undertake, before or since.”

It’s also important to remember, Graff pointed out, that the process of getting Richard Nixon out of office wasn’t as smooth as it seems in hindsight.

“Richard Nixon almost got away with it,” Graff pointed out. “There are a good half-dozen moments in between the summer of ‘72 and March of ‘73, where Richard Nixon almost succeeds in shutting down the investigation and getting the whole thing behind him.”

It wasn’t really until Alexander Butterfield’s Senate testimony in the summer of 1973 that Nixon had secretly taped all his Oval Office conversations, leaving a trove of firsthand evidence, that America’s understanding of the scandal really changed, Graff said. And not until the Saturday Night Massacre of October 1973 — in which Nixon demanded the firing of special prosecutor Archibald Cox and went through three attorneys general in one day until future Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork did the job — that public opinion began to turn against the president.

Worse than Watergate?

It didn’t take long for the phrase “worse than Watergate” to enter the political lexicon either, and in 2018 Politico published a list of 46 scandals that were described thusly. After spending years studying the original item, were any of these incidents actually worse?

Graff said you don’t have to look far.

“I actually, very much believe that the Trump administration was worse than Watergate.” He said the last administration shared the structure of “interrelated and overlapping scandals” stemming from a similar “criminal and corrupt mindset. … And this time, unlike Watergate, Trump escaped the presidency without consequence.”

A new Watergate?

The other common question that’s been pondered seemingly since 1974 is whether Watergate could happen again — whether a break-in at a major party office orchestrated by the other party would result in the resignation of a president and the jailing of high government officials who were involved.

Graff felt it wasn’t likely because there’s a different environment today, both in politics and in media. In the early 1970s, the notion that a president would lie to the public was world-changing. Nowadays, in part thanks to Watergate itself, it’s something most Americans take in stride.

“The other thing, obviously,” Graff said, “is the difference in the media landscape — both the speed and ephemeral nature of social media, and then the very robust and powerful right-wing media ecosystem headed by Fox News and conservative talk radio that would, in the modern era, protect the president — protect a Republican president.”

Nixon, in the end, committed the two greatest crimes someone can commit against their own country: prolonging a war in which Americans were dying and interfering with an election. And other than resigning the presidency, nothing else happened to him: His predecessor, Lyndon B. Johnson, knew about the Chennault affair and didn’t say anything; Nixon’s successor, Gerald Ford, pardoned him weeks after he resigned for his involvement in Watergate.

Graff said that was an indication of the power the office of the presidency had, and still has. “One of the things that becomes clear, in both the story of Watergate and the story of the Trump administration, is that our country really struggles with how to confront a criminal and corrupt individual once they reach the Oval Office. … The best thing America can do to prevent a future Watergate is to keep corrupt and criminal presidents from office in the first place.”