I lived at 112 Tyler St. for most of my college years. The rickety, old white house was right outside the gates of Hampton Institute, a historically Black college in the Tidewater area of Virginia.

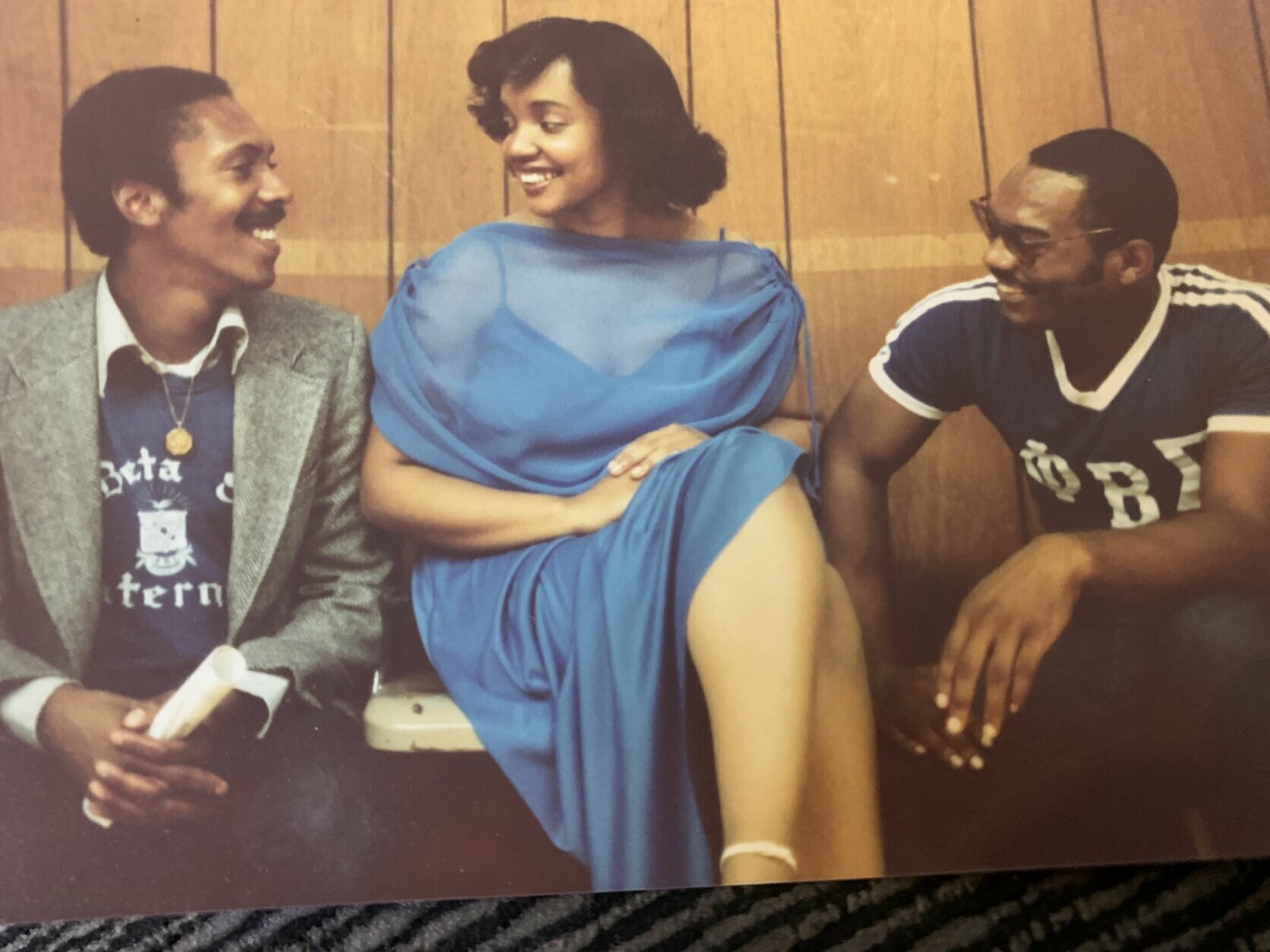

If walls could talk, the walls at 112 Tyler St. from 1980 to 1983 would tell you about hourslong talks between me, my roommate Jameta Rose and dozens of friends who floated in and out of our doors over the years. We would sit around solving the world’s problems with our 20-something logic and naïve solutions. The question was usually, “What should Black people do now?”

The civil rights movement had ended, Ronald Reagan was president and rap music was still in its infancy. We had grand hopes of changing the world, but until then, we were determined to heed the lyrics of Prince and party like it’s “1999.”

When I look at Vice President Kamala Harris, I can’t help but think of those days and feel a sense of pride.

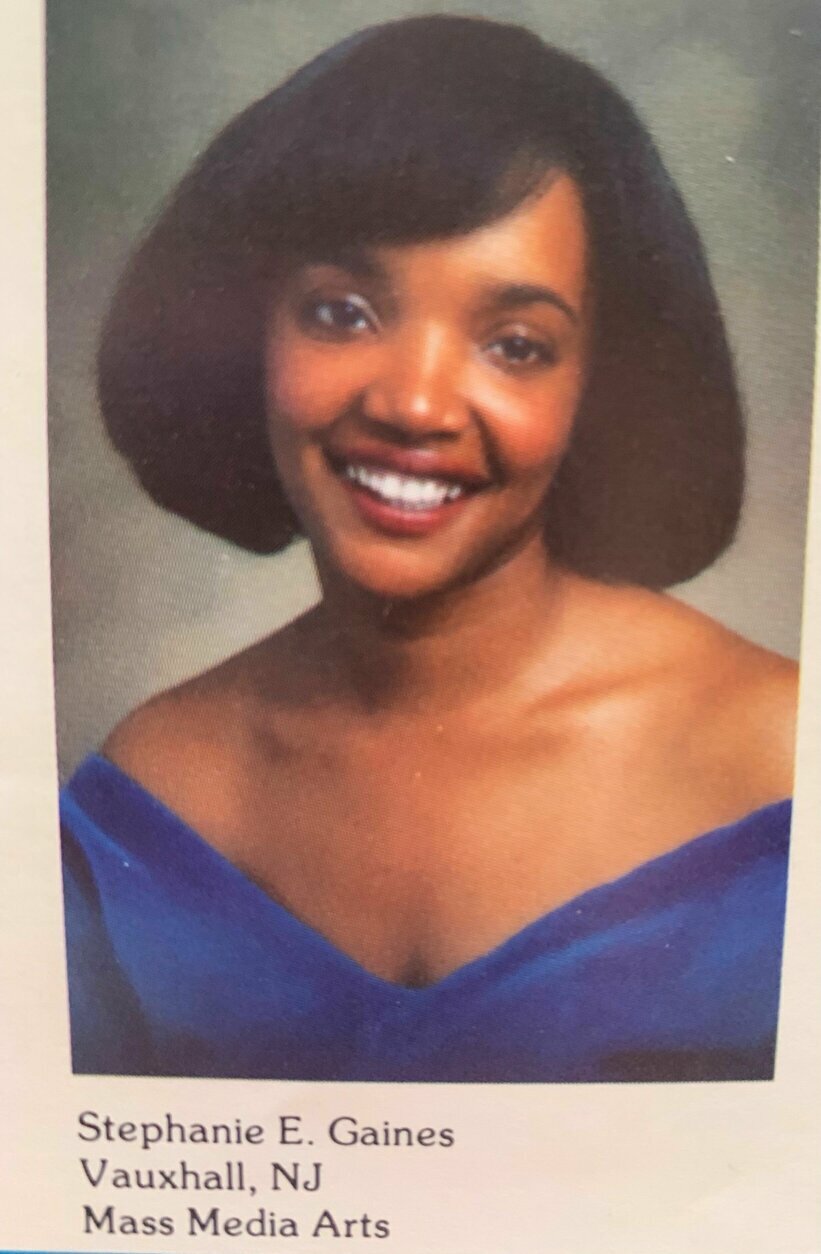

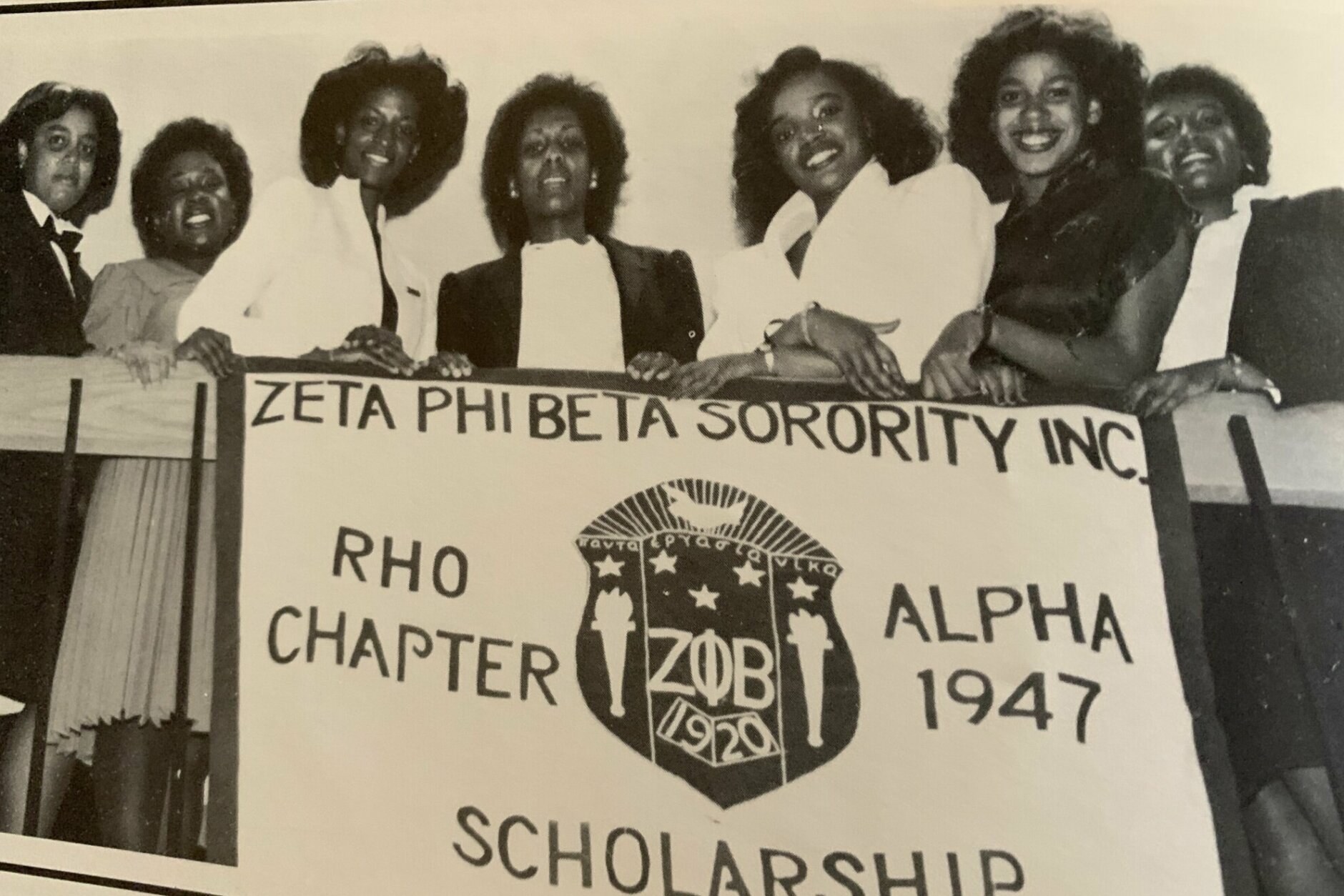

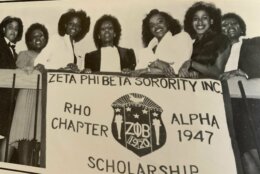

Yes, we attended different HBCUs: She attended Howard University, and I attended Hampton. She joined a different sorority: I’m a member of Zeta Phi Beta; she’s a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha. She’s from a different part of the country: Harris is from California; I am from New Jersey.

But she is all of us. All of those women during 1980s and 1990s who graduated from HBCUs or PWIs (predominantly white institutions), ready to set the world ablaze.

Some of my friends went off to law school or medical school. Some went to work for government agencies. Others for large corporations. I somehow stumbled into radio, working first as a DJ, then as a news anchor. Some of us became wives and mothers.

After a devastating divorce, I met and married my husband of 28 years and gave birth to four children. Other peers became single mothers through divorce or circumstance. Others, like Harris, joined blended families.

But most of us know what it’s like to don our Superwoman cape each and every day and keep plowing ahead even when it would be much easier to surrender to hopelessness.

Our cape was handed down by our mothers and our mothers’ mothers. They wore it despite its heaviness and the unfair labels that came along with it. Then they lifted us up with calloused hands and placed us on their weary shoulders in hopes that we would be able to travel roads unavailable to them.

My own mother, who worked as a nurse’s aide for over 40 years, saw her eldest daughter become a nurse manager at a major hospital in New Jersey. My paternal grandmother had to give up her teaching career when she and my grandfather migrated north from Virginia during the First Great Migration.

This was because the school system in her new community wasn’t hiring Black teachers. She lived to the ripe old age of 92, but it wasn’t long enough to see her two granddaughters, a grandson and two great grandchildren become teachers. Harris’ mother did not live to see her daughter be sworn in as the Vice President of the United States.

Black women have been portrayed as either a Jezebel — the hyper-sexual temptress — or a mammy, the asexual caretaker. These days, Black women are often portrayed as angry — hips switching, necks rolling, lips smacking, full of attitude.

The “angry Black woman” is perceived as having a high tolerance for pain and a low tolerance for mankind. Even souls as warm and genuine as Michelle Obama have been warned to smile more and shout less or she will be labeled as angry.

But in the words of the late poet Maya Angelou: “And Still I Rise.”

Despite the challenges, we have risen to lead major cities, such as D.C., Atlanta, Chicago and San Francisco. We have risen for justice to make sure all people are allowed to exercise their right to vote. We have risen to heal the sick with registered nurse or medical doctor attached to our name. We have risen to raise our babies and our voices, to govern great democracies.

Kamala Harris is us, and we are her.