This is Part 2 of a three-part series on WTOP.com about DNA evidence, its evolution and how it’s being used in the D.C. area and beyond.

READ PART 1: A Reston company that helps police crack DNA evidence

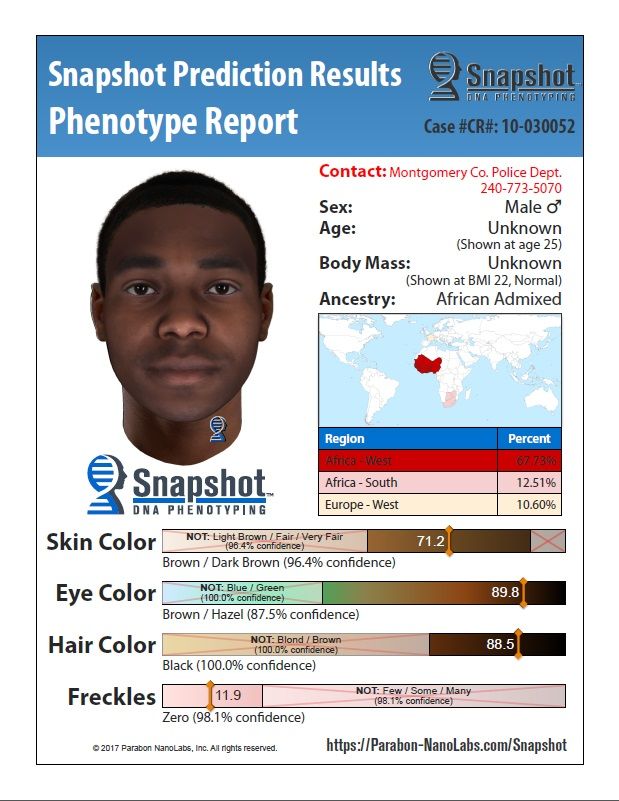

In 2007, police in Montgomery County, Maryland, were investigating an attempted rape inside a Gaithersburg apartment. It was thwarted by the victim, a woman in her mid-20s who happened to be a cop. However, the only lesson the suspect evidently learned was that he needed to attack older victims who lacked the strength and ability to fight back.

His next victim was a 68-year-old woman. Then he raped a woman in her 80s. A few months later, he went back and raped the 68-year-old woman again.

For more than a decade, he remained free — the DNA collected from the crime scenes only confirmed that it wasn’t done by anyone who had committed violent crimes before.

The break police needed to make an arrest came from Reston, Virginia-based Parabon Nanolabs, which took the DNA evidence and eventually linked it to Marlon Alexander, of Boyds, Maryland.

Alexander “wouldn’t have been on the radar unless we worked with Parabon,” said Sgt. Christopher Homrock, who heads the Montgomery County Police Department’s cold case squad.

The DNA connection led to a guilty plea last year, and earlier this year Alexander was given a pair of life sentences for the attacks.

This was one of a handful of cases the Montgomery County police gave to Parabon last year. The software company has spent the last 10 years looking at DNA in different ways, and then leapfrogged from there into genetic genealogy after the arrest of the Golden State Killer last year. They’re among the private companies police departments around the country are turning to, hoping that unknown DNA picked up from a crime scene still holds enough detailed information to solve those cases.

Sgt. Christopher Homrock, who leads the Montgomery County Police Department’s cold case unit, called genetic genealogy “the up-and-coming thing in cold case investigations.” He said more than a dozen cases tied to three suspects, some of them decades old, have been closed by leads generated by Parabon, and dozens more are being advanced. Homrock relies on DNA information, genetic genealogy and the diverse investigative background of his squad — and an officer they call Smugs.

Meet ‘Smugs’

“I’ve gone back in some trees five generations or further,” said Montgomery County Police Officer Steven Smugeresky, who typically goes by Smugs. He normally patrols downtown Silver Spring on a bicycle. He’s not even on Homrock’s cold-case unit, but he has also become the guy the cold case squad turns to when they need to connect a distant relative to a suspect.

He got his start in genealogy when he was still a cadet in the police academy in 2002. He noticed that plaques remembering all fallen Montgomery County officers adorn the walls of the police academy, but there’s no picture for the first one — Joseph Case, who was killed in 1928.

Case had no children, but Smugs used a marriage certificate, an obituary and census records from 1900 and 1910 to run back through Case’s family tree, find his ancestors and trace forward to find relatives who are alive today. They now participate in ceremonies honoring Case and other officers who died on the job. “Still haven’t gotten [the photo] to this day, but I’ve done a lot of research,” he said. And it all came through free public databases.

How cold cases really get solved

If this were a TV show, when Parabon returns a report with the name of an ancestor, police would just plug the name into a computer and within 20 seconds have family trees traced and the suspect identified. A minute later, you’d see the suspect get arrested and the show would end.

But when Homrock gives Smugs a name from Parabon, it might be days or weeks or months before the suspect is identified.

“You’d be amazed at how many people have the same name, and how many people come from the same areas,” Smugs said. “I’ll go down a rabbit hole for like two to three days searching this person and then finally, ultimately, he’s not even connected … to the family tree. So then that’s three days of work down the drain.”

A lot of that work might get done in libraries on old newspapers saved on microfilm, in a search for an obituary for someone who might list further descendants who can help fill in gaps on the family tree. It can be as tedious as going through a month or a year’s worth of newspapers looking for one little announcement.

Sometimes it’s even more than that.

“I’ll walk around the cemetery and find a headstone and then walk around where that person was buried and find other people with common names, dates of birth or dates on their stones,” said Smugs. “I’ll take pictures and I’ll come back and throw all those names in different genealogy sites to see if I can come up with any kind of death records or any kind of death certificates or birth certificates connecting them to that person.”

Homrock said his detectives have backgrounds in forensics, child-abuse cases, financial-crimes cases, robbery cases and more. “Each of our cases usually has one of these aspects as the motivation behind the crime,” he said. “When Smugs is working on a family tree, we are running a parallel investigation and usually Smugs and the detective meet in the middle with the same name.“

Cases closed

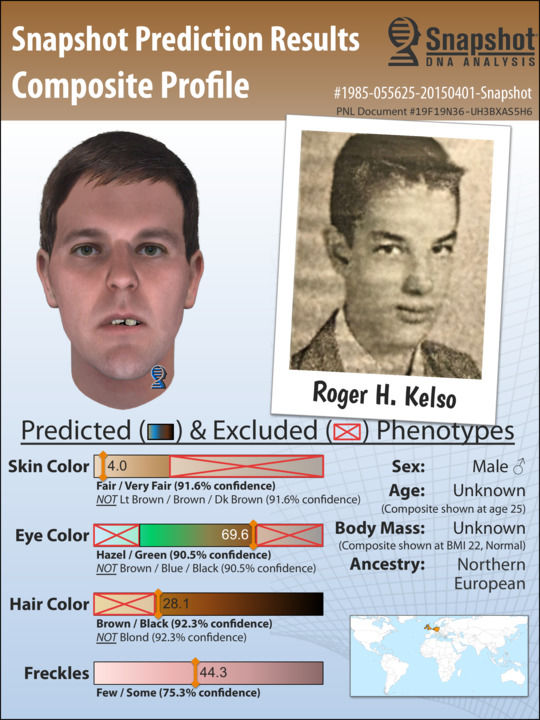

Back in June, Anne Arundel County police held a news conference to announce that they had finally identified a murder victim whose body was found in a trash can in 1985, when Marley Station Mall in Glen Burnie was being built.

“It was the worst crime scene I’ve seen as far as evidence goes,” said retired detective John Jaschik. His crime scene had been excavated and destroyed by bulldozers and earth movers. But 20 years after retiring, he returned to hear about the break in the long-vexing case.

All they knew about the victim was he was carrying seven coins. The newest one was minted back in 1963.

It took 56 years for police to identify the victim as Roger Kelso, giving siblings who hadn’t seen him since 1962 the closure they had long dreaded but assumed.

Anne Arundel County police and Parabon had worked together on this case before, using Kelso’s DNA to come up with composite pictures of what they thought he looked like. Once Parabon began doing DNA genealogy last year, it led to the biggest break the case had ever gotten.

“The new technology, I can’t speak well enough of,” said Detective Regina Collier. “Without that I would still be not even knowing who my victim was.”

Kelso’s sister said it was reassuring to know that the police still cared about her brother, and weren’t ready to give up. For Collier, it was the second big break in a case she’d gotten from Parabon.

In 2010, Michael Temple of Odenton was shot during a home invasion. The two people who broke into his home were wearing masks, and in the ensuing struggle one of the suspects ended up leaving behind some DNA police were able to extract.

But the attack left Temple a quadriplegic, confined to a wheelchair. When he died in 2015, an autopsy determined Temple’s death was a direct result of the shooting in 2010. It became a murder case.

Last year, police sent the unknown DNA to Parabon, and their report led police to 32-year-old Frederick Frampton, of Glen Burnie.

“He was charged and actually he just [pleaded] guilty,” Collier said in June. The second suspect died a few months before Frampton’s arrest, police said.

There was a similar ending in a series of other cases connected to one suspect in Montgomery County, too.

For 30 years, a man connected to multiple rapes near the Rockville Metro station in the 1980s and 1990s, including one that left his victim dead at her home, had managed to elude police despite numerous arrests over the years on several other minor charges.

Then they submitted the suspect’s DNA to Parabon, and Smugs got busy with the results that came back.

“I was able to go back about three or four generations, and we had two shared matches in that,” said Smugs. Most of the family lived out of state, but he found one piece of information putting Kenneth Day’s father in Silver Spring. From there he went through law enforcement databases to look up more info on Day and “everything started to pop at that point. I looked at his previous addresses and it put him within the scene of the crime.”

By that point, Day had already been dead for two years, after overdosing on drugs in 2017 in West Virginia. Still, the Montgomery County police were able to match the DNA they had from the original crimes with the blood sample the West Virginia Medical Examiner had after Day passed away.

Listen to John Domen’s series

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

In our final installment on Friday: This new technology raises new questions about privacy, as well as whether it’s in conflict with a law that’s already on the books in Maryland and D.C.