WASHINGTON — Like migrating birds that return to their nests each year, a new study shows that the cownose ray found in the Chesapeake Bay does something similar, and that could have implications for how states such as Maryland and Virginia manage the ray populations.

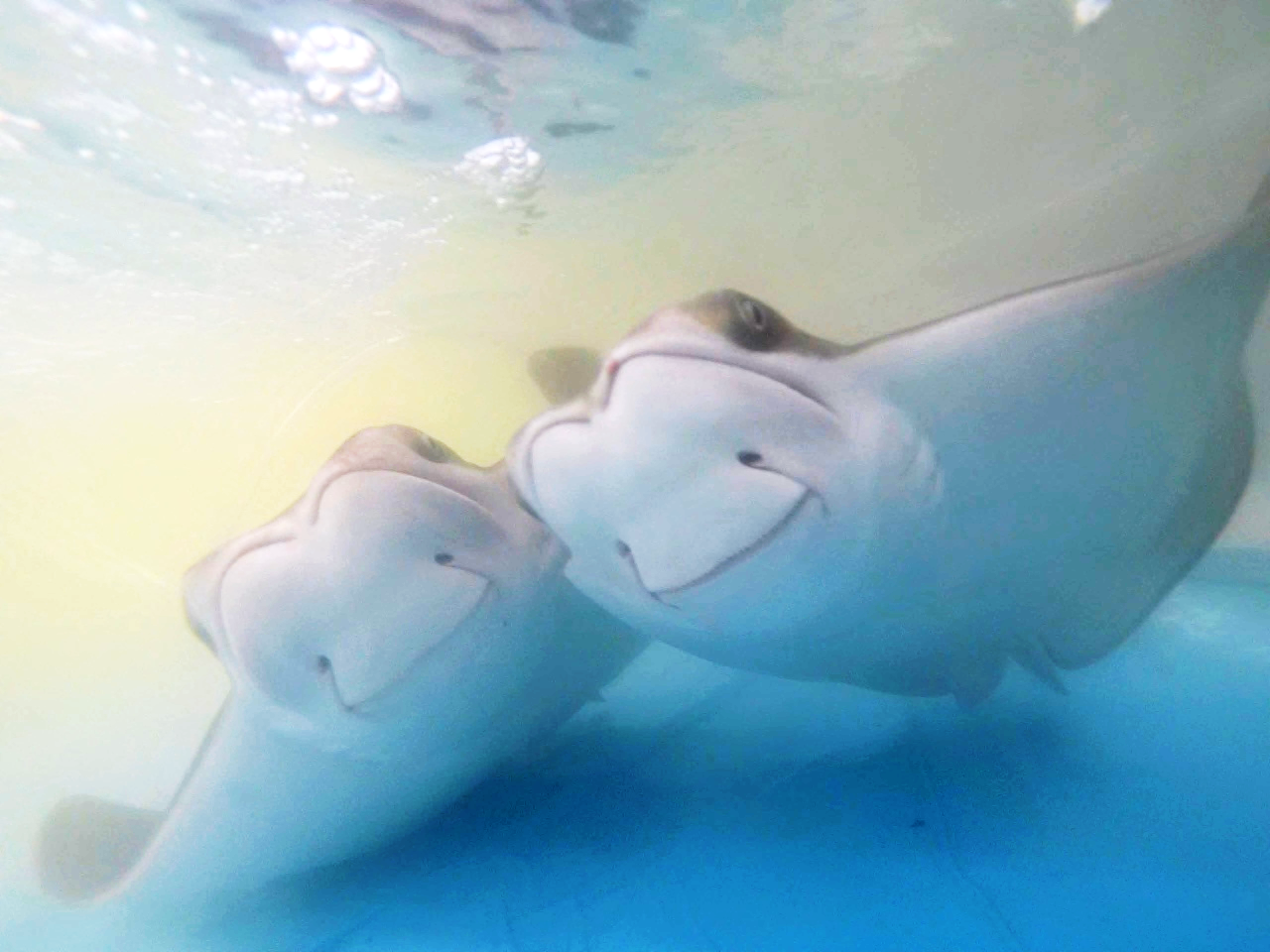

If you’ve been to an aquarium, you may have actually touched a cownose ray; they’re often part of “touch tank” displays, where aquarium visitors can see the animals up close.

“They’re a kite-shaped brown ray that has two bumps on the head that look a bit like the nose of a cow, which is how it got its name,” said Matt Ogburn, co-author of the study and a marine ecologist with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center in Edgewater, Maryland.

The SERC study tracked a group of 42 rays and found that they take off for Florida in the winter. But, when the weather warms up and it’s time to raise a family, the rays, which travel in large schools, return to the areas of the Chesapeake Bay where they were born.

Ogburn said there hasn’t been a lot of research on the cownose ray, but he said, “It’s at least a good possibility that the rays are important to maintaining healthy clam populations.”

He said a Virginia study shows that in areas where the rays feed, there’s a greater diversity in the populations of bivalves — clams and oysters. “There’s a good potential that that’s important to the way the bay functions when it’s healthy,” Ogburn said.

Watermen complain that the rays, which travel in large groups, can devour an oyster bed — and the watermen’s investment — in no time.

In Maryland, the rays have been targeted in fishing tournaments, but in 2017, the General Assembly passed legislation that instituted a moratorium while the state studies the issue.

Ogburn said that the Maryland Department of Natural Resources has been provided a copy of the study, as it drafts a fishery management plan.

“We’re not advocating for a particular position or strategy of management,” Ogburn said, but he added, “We need to be cautious about the way that it’s done.”

“The motivation for this research is not to try to stop fishing — it’s just to understand the biology,” Ogburn said.

He added that rays don’t begin to breed until they are almost 6 years old; pregnancy in females lasts nearly 12 months. And, when they do have their young, they have a single pup at a time.

Ogburn said that overfishing could push them into endangered status. And, if research shows that the rays play a critical role in the health of the bay, the effects could go beyond cutting the ray population.

“We’re really just trying to answer the question, ‘What’s the right scale to manage the species?’” Ogburn said.