In the U.S., new and expecting moms die at a rate that’s higher than other developed countries, and cases of close calls are on the rise. D.C. is among a handful of states with the highest maternal mortality rates. In our three-part special report, Dangers of Childbirth, WTOP looks into why.

WASHINGTON — On Dec. 5, 2017, a pregnant Alexis Squire sat in a hospital bed in Northwest D.C., her husband by her side.

She was in a gown, hooked up to wires and excited to finally meet her son. Having traveled an hour from her home in Southeast D.C., she sensed the light at the end of a dark tunnel.

For the couple, it had been a bittersweet journey. The year before, Squire, 35, had a miscarriage, hemorrhage and emergency surgery. After the heartbreak of losing the baby, the Squires were excited to discover Alexis was pregnant again. But because of her history, and with a few new complications, Squire was considered a high-risk patient.

With this pregnancy, her obstetrician directed her to come in for an induction at 39 weeks because the baby could get too big. It was finally time to meet her son — but something was wrong.

A doctor, not her obstetrician, entered the room and asked why she was there.

“All of the mental preparation that goes into having a baby, especially in light of my losing the first one — I was just so taken aback by that,” she said.

Despite her obstetrician’s instructions, this doctor said the induction process was voluntary.

“I don’t know what that means. I don’t know what that term means. My doctor told me to come here,” Squire said she remembers thinking.

Another doctor came in and told Squire the same thing: She had the option to go home, and they were unable to reach her doctor to clarify whether she needed the induction.

Squire and her husband decided to stay for the induction. It was a long labor, followed by another hemorrhage, but Squire finally got to meet her son, Alexander.

“I remember my doctor came by and he said, ‘You’re all right.’ And that was that,” Squire said.

A few days later, she left the hospital with a new baby, but also a feeling of disappointment from the overall experience — the confusion and the lack of a “warm-and-fuzzy feeling” she hoped to receive during a major life event.

“I didn’t feel valued. Even when I got to the hospital, I didn’t feel like they were listening to what my concerns were, my history,” Squire said.

‘There is a distrust’ when it comes to care

For high-risk mothers east of the Anacostia River, there are no options for delivering a baby close to home.

There are community-based clinics and birthing centers, but in 2017, two hospitals on the eastern side of the city, United Medical Center and Providence Hospital, closed their maternity wards — UMC for reported medical errors and Providence for reported cost-saving measures.

That means women in Wards 7 and 8 — an area that’s predominantly black and disproportionately poorer and sicker than the rest of D.C. — have to travel to western parts of the city if they want or need a hospital delivery.

Squire, who was born and raised in D.C., said that when she and her husband bought their home in Fort Dupont, their focus was a house with a yard for the family they always planned. Access to high-risk care wasn’t something she considered.

“I shouldn’t have to go an hour-plus to get what I think is quality care. That’s just ridiculous,” she said. “And it’s a risk to everyone involved.”

In recent years, and before the shuttering of UMC and Providence’s labor and delivery services, the city invested millions of dollars to bring new and renovated health care centers to previously underserved communities. One example is Community of Hope’s Conway Resource Center, just off South Capitol Street in Ward 8. At the 50,000-square-foot facility, residents have access to medical care (including prenatal and pediatric), dental and behavioral health care.

Carla Henke, chief medical officer at the clinic, said when the building first opened four years ago, traffic was slow. But now, the clinic’s patient population is “rapidly growing.”

“We learned over time that this is a community that thrives by word of mouth, and we work to build trust in the community, and I think we’ve built that now and are starting to see more patients because of that,” Henke added.

Still, data show that most residents living in Wards 7 and 8 seek care outside of their ZIP codes.

Ebony Marcelle, director of midwifery at the Community of Hope birthing center in Northeast D.C., said it’s going to take more than simply letting people know that these community-based clinics are there and ready to serve.

“I think, overall, there is a distrust with the hospital institution, or medical institution, period,” said Marcelle, who cited historically significant cases such as Henrietta Lacks, whose cells were taken without consent for research, and the Tuskegee experiment, where black men with syphilis were followed by the U.S. Public Health Service for decades, without being treated with penicillin, even as they died or went blind or insane.

Marcelle said there are ways to overcome this barrier. “I think all of us could (benefit from) some implicit bias trainings,” she added.

It’s something midwives and maternal health grass roots organizations around the country are working on, including Black Mamas Matter, ROOT (Restoring our Own Through Transformation) and the National Association to Advance Black Birth.

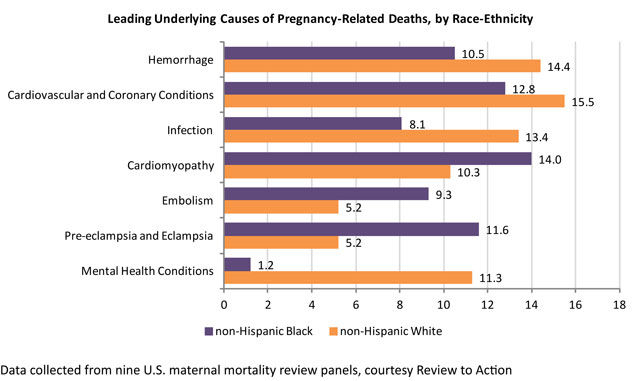

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists also made addressing racial disparities a focus in its Alliance for Innovation in Maternal Health program after noticing a trend in California’s declining maternal mortality rates. Both non-Hispanic white women and black women saw decreased rates of mortality, but black women still had a higher rate of death than white women.

“So what that means is that the disparities are still there, even though the absolute numbers are smaller,” said Dr. Barbara Levy, a physician and vice president for health policy at ACOG.

Nationally, black women experience maternal mortality rates up to four times higher than their peers. In 2011, the maternal mortality rate for non-Hispanic white women was 12.5 deaths per 100,000 live births. That same year, the rate was 42.8 deaths per 100,000 live births for black women.

Research shows just how much of an impact stress fueled by centuries of racial discrimination has on one’s health. According to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the average life expectancy for a black man in 2009 was 71, compared to 76 for a white man. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation reports that every seven minutes, a black person dies prematurely.

‘It’s time for us to have some harder conversations’

A day after coming home from the hospital with her new baby, Squire said she had a bad headache and some spinal pain.

“It was not going away, and my feet and my legs started to swell up really, really bad,” she said. “But you know, you’re all in baby mode at that point.”

She called the obstetrician’s office, and was told to keep an eye on it, so she did. But she also scheduled an appointment with her primary care physician, a black woman, in Silver Spring, Maryland. There, Squire learned she might have postpartum pre-eclampsia, a condition that occurs when a woman has high blood pressure and excess protein in the urine after childbirth. Complications from the condition can be life-threatening.

The doctor ran some tests and told her, in the meantime, if the headache got worse, she needed to go to the emergency room.

One day later, that’s exactly where Squire landed, hooked up to a magnesium drip with her newborn on her lap.

“It just was quite a process,” she said.

Throughout her prenatal and postpartum care, Squire said she felt like everything was “rushed,” and that her concerns weren’t addressed or seriously considered.

“I don’t know. I just felt like maybe they thought I was being a little high-maintenance,” Squire said.

She can’t help but think that part of her less-than-ideal experience was because of her race.

Squire added, “And then also when you hear (about) Serena Williams basically having a very similar experience of people not listening to her and not valuing that she knows best and most about her body and her care.”

In February, two months after Squire gave birth, tennis superstar Serena Williams shared that she nearly lost her life to post-birth complications from a blood clot and hematoma. A profile in Vogue describes Williams’ attempts to alert doctors to her condition, which was not immediately addressed.

Williams’ experience brought attention to the importance of self-advocacy in prenatal and postpartum care. Levy, from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said there needs to be better communication between patients and providers across the board.

“We need to help people articulate in a way that our providers and the health care system can hear us. Because it’s not just doctors, it’s not just nurses. It’s EMTs, it’s emergency rooms, it’s everyone. All of us have that implicit bias that a woman who’s pregnant or postpartum is healthy, and so we don’t think about the things that could be drastically wrong,” she said.

Marcelle said when it comes to caring for black mothers, in particular, even more needs to be done.

“If you look at the [maternal health] data, we thought, ‘Oh, it’s socioeconomic. Oh, it’s prenatal care. Oh, it’s this.’ We’ve got probably like 70 years of data and it’s not changing,” she said.

“We’re the only developed country where maternal mortality is going up. So it’s time for us to have some harder conversations about the stress, the chronic stress, the microaggressions, racism living in this country … and about trying to create systems that can work for women, and not create systems that are convenient for us.”

More from the series, ‘Dangers of Childbirth’

Part 1: DC works to save dying mothers

Part 3: US sees ‘many deaths,’ even after baby arrives