In the U.S., new and expecting moms die at a rate that’s higher than other developed countries, and cases of close calls are on the rise. D.C. is among a handful of states with the highest maternal mortality rates. In our three-part special report, Dangers of Childbirth, WTOP looks into why.

WASHINGTON — Jade Wexler’s memories of childbirth are a far cry from those depicted in Hallmark movies and Pampers commercials.

Some of the details are still a blur; others are too traumatic to shake.

“I just remember feeling like a rag doll on the table because I was awake when the doctor and everybody were trying to stop the bleeding,” she said.

Wexler hemorrhaged shortly after delivering her son via a C-section in March.

“It was, yeah, a pretty messy scene. … (The doctor) came back and talked to us later about how I lost a lot of blood and really could have died,” said Wexler, a resident of Chevy Chase, Maryland.

Over the course of her stay at a hospital in Northwest D.C., Wexler, who was diagnosed with HELLP syndrome — a pregnancy-associated condition that results in hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet counts — required four blood transfusions. She didn’t get to meet her newborn son until her second night in the hospital.

“I was so out of it, I couldn’t go see him. I remember being there and saying, ‘Didn’t I just have a baby?’ But I didn’t have a baby next to me and I was in intensive care,” Wexler, 42, recalled.

Wexler’s near-death experience is one many women in the U.S. encounter. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of women who face severe maternal morbidity — which is defined as unintended outcomes from labor and delivery that result in short-term or long-term consequences to a woman’s health, such as a hemorrhage — has increased almost 200 percent in recent years, from a rate of 49.5 per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations in 1993 to 144.0 in 2014.

The number of women dying from childbirth is also on the rise.

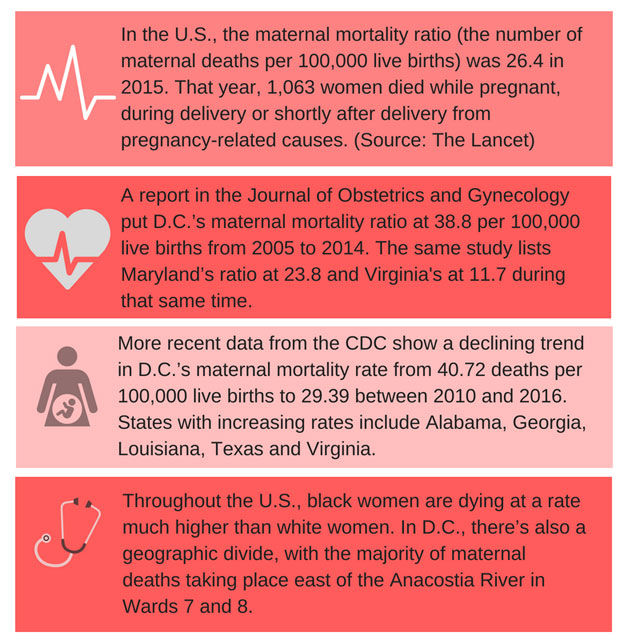

While global maternal mortality continues to decline, the estimated ratio in the U.S. more than doubled between 1993 and 2013, from 12 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births to 28, the World Health Organization reported.

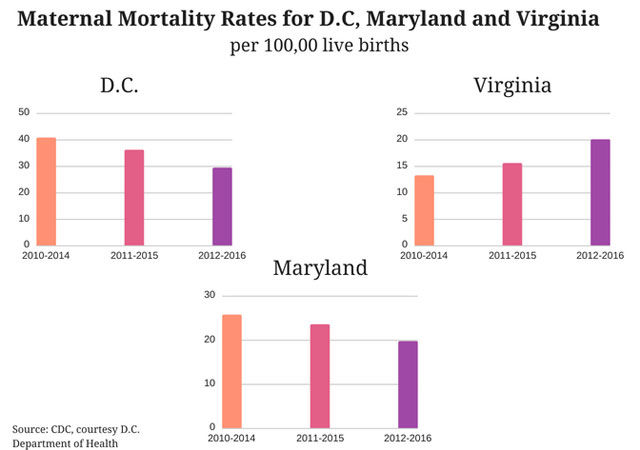

In D.C., one of the wealthiest and most educated cities in the country, the maternal mortality ratio was nearly double the national average between 2005 and 2014. It has since dropped, but is still above the national average. That is why this fall, a multidisciplinary panel of experts will meet for the first time in an effort to better understand what’s threatening, and sometimes taking, the lives of new mothers.

For this series, WTOP interviewed policy makers, physicians, patients and experts in the field of women’s health to report on what the public can expect to see from D.C.’s first maternal mortality review panel, as well as factors that are driving increasing rates of maternal morbidity and mortality, and what’s being done to reverse the trends.

Breaking down the facts, working to break new ground

A maternal death is defined by WHO as the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.

“We know that we have too many moms that die, and we know that we can do a lot better than that,” said Ward 6 D.C. Council member Charles Allen, who proposed legislation calling for a maternal mortality review panel to investigate D.C.’s deaths.

Thirty-three states in the U.S. already have panels in place, including Maryland and Virginia.

Allen added, “We need to look at access to care; we need to look at the quality of care; we need to look at geographic distribution of care; we need to look at what is driving a racial disparity in that black and brown mothers die at a rate of three to four times their white peers. That’s what we want the review commission to look at, but we have to, at the same time … be aggressive as we look at what are other interventions and ways that we help.”

Dr. LaQuandra Nesbitt, director of D.C.’s Department of Health, does not deny the need for an increased focus on maternal health and mortality, but said one reason why D.C.’s reported ratios are so high is because the city has a much smaller population than the states to which it’s compared.

For some perspective, D.C. had a total of 9,264 live births in 2013. Virginia reported 100,618 live births in that same year, and Maryland saw 71,806.

“Now we want to be very clear with people that one person dying from anything is too many, especially when it comes to being something that is preventable,” Nesbitt said.

Some research shows that about 60 percent of pregnancy-related deaths in women are preventable.

“And our charge, and my charge, in particular, … is to make sure that anything that’s preventable, that we’re putting our best foot forward and all of our efforts forward to make sure that we, indeed, prevent those deaths,” Nesbitt said.

What, exactly, are women dying from?

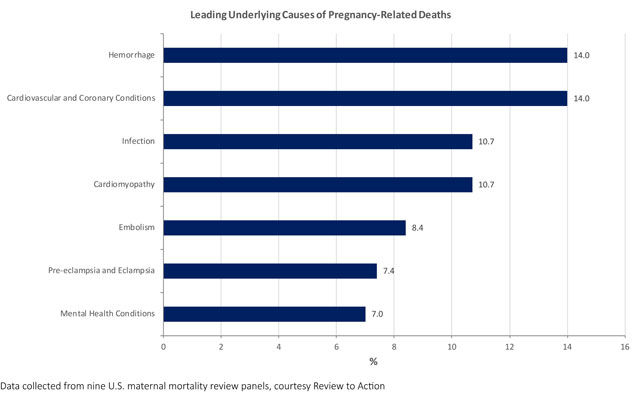

New and expectant mothers are dying for multiple reasons, and the problem requires multiple solutions. Dr. Barbara Levy and her colleagues at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have been working for years to get the right systems in place to reverse the trends.

Levy said some experts think health professionals are doing a better job classifying and counting deaths, and that’s why we’re seeing an uptick in maternal mortality rates, but “that’s probably not most of it.”

The greatest cause of maternal mortality, she explained, is cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death for women in the U.S.

“And you wouldn’t think about that,” said Levy, a physician and ACOG’s vice president for health policy. “We think about pregnancy in young, healthy women, but as women become more mature when we have babies, we can have underlying health conditions.”

Jade Wexler, who went into intensive care after experiencing a post-delivery hemorrhage in March, always considered herself a healthy person. So when her doctor told her at a prenatal visit that she had gestational diabetes, she was shocked.

“It blew my mind because I thought I was so in shape and this doesn’t happen to people who are in shape. But it doesn’t matter,” said Wexler, who also experienced Bell’s palsy, excessive swelling and elevated blood pressure toward the end of her pregnancy.

In a lot of cases, pregnancy causes previously unnoticed health conditions to worsen, said Dr. Constance Bohon, an obstetrician-gynecologist and associate clinical professor at George Washington University.

“You can be prediabetic and become diabetic in pregnancy. Some women can have high blood pressure and it gets worse in pregnancy,” Bohon added.

The body takes on an increased workload in pregnancy. When a woman is pregnant, her blood volume increases by about 50 percent to help support her circulation and the baby’s, and that added volume has to be handled by the heart, kidneys and other organs.

“And so we see what were undiscovered problems that come to light during pregnancy because of the added load,” ACOG’s Levy explained.

Experts say these physiological changes are why it’s important to have early and frequent access to prenatal care. At the monthly, bi-weekly and weekly visits, mom and baby’s health are routinely monitored throughout the pregnancy, and plans for delivery are discussed.

Bohon said, “One of the biggest concerns is women who don’t get into prenatal care early enough, and then when they come to the hospital for delivery, their glucose is out of control or their blood pressure is very high. Then we have to get the baby delivered and take care of the mom in a crisis situation. So it’s hard to get her stabilized when we’re dealing with numbers that are really potentially catastrophic.”

But in D.C., and for a variety of reasons, not all expecting moms receive prenatal care. According to data from the D.C. Department of Health, out of the District’s combined live births in 2015 and 2016, 12,759 women accessed prenatal care in the first trimester, 5,575 delayed care until later in the pregnancy, and 464 never went to the doctor. In other words, roughly one-third of women who gave birth during that time period either accessed care later than advised, or not at all.

Maternal health’s racial disparity

The Health Department’s Nesbitt confirmed that maternal mortality rates “tend to be higher in communities where access or entry into prenatal care is delayed or doesn’t occur at all.” This is especially the case among minority populations.

Only about 52 percent of black women in D.C. receive prenatal care in their first trimester, compared with 86 percent of white women, Nesbitt said

“So we believe that may be an indication or a risk,” Nesbitt added.

For women east of the Anacostia River, where the majority of D.C.’s maternal deaths are concentrated, prenatal care hasn’t always been easy to access — in previous decades, some health care was administered in windowless grocery stores and huts. More recently, two hospitals that served women in Wards 7 and 8 (Providence and United Medical Center) closed their maternity wards.

But Nesbitt said the city has made significant strides to bring primary and prenatal care to these communities with several new and expanded health care facilities, financed by the District’s Tobacco Settlement Funds. Community of Hope’s Conway Health and Resource Center, which opened in 2014, is one place where expecting mothers in Southeast can access prenatal care.

Carla Henke, the center’s chief medical officer, estimated the clinic saw about 400 patients for new obstetrics visits in 2017. Its services to pregnant women include monthly visits with a midwife, group “centering” classes, time with a doula — even breast-feeding and postpartum care.

Just off South Capitol Street in Ward 8, the clinic also provides its patients with a care coordinator to help women stay on top of their pregnancy care and prenatal appointments, which increase in frequency as delivery nears.

This comprehensive approach only goes so far, however. Those who experience complications often have to seek additional care.

“When things get outside of our scope, there are some barriers even for us, as providers, for being able to help our patients navigate the system to access high-risk care,” said Megan Hollis, medical director at Community of Hope’s Conway Health and Resource Center.

Making care accessible to all

Alexis Squire, 35, drove from her home in Southeast D.C. to Bethesda, Maryland, for prenatal appointments during her most recent pregnancy. She required extra care after her first pregnancy resulted in a miscarriage, followed by a hemorrhage and emergency surgery.

The commute often took her an hour — “on a good day” — for what would sometimes be a 10-to 15-minute appointment.

Squire, who works in communication, has a car and family support in the area, but not everyone does. Bohon cited a recent example of a Southwest D.C.-based patient who had an appointment in Northwest D.C. at 11 a.m., and the only transportation she could find picked her up at 6 a.m.

“That just can’t be,” Bohon said.

“We have to make it easy for women to get to their appointments in a very timely manner, so they don’t have to worry with compromising their job or what to do with their children. And then we also need to make sure that when they get to their provider, that they get the care that they deserve and the care that they need.”

Research shows that even if prenatal care is available, barriers, such as securing child care for additional children and getting the time off work, prevent women, especially those living in inner-city neighborhoods, from going to the doctor.

The Health Department’s Nesbitt said D.C. is working to address access-to-care barriers, and part of it starts with letting women know the new facilities are there and open.

“We really find it (concerning) that in 2018, we have an existing narrative out there that there’s nowhere in Wards 5, 7 and 8 for women to get access to prenatal care,” Nesbitt said.

Unity Health Care, another leading prenatal provider in Southeast D.C., is also the recipient of funding from the city’s tobacco settlement. It has several locations that offer obstetrics care in underserved communities. Still, data show that the majority of residents living in Wards 7 and 8 seek care outside of their ZIP codes.

“(We want to) make sure that women understand that those providers are there, they’re in the community, they’re providing culturally competent and compassionate services to women,” Nesbitt added.

Henke said she has learned over time that in the area Community of Hope serves, word-of-mouth is still important. She said the clinic has been working to build trust in the community, “and I think we’ve built that now and are starting to see more patients because of that.”

Learning from others

Since Virginia started its maternal mortality review panel in 2002, several cause-of-death patterns have emerged in the more than 500 cases studied.

HELLP syndrome and pre-eclampsia are still among the leading causes of death in the state, said Melanie Rouse, Virginia’s maternal mortality projects coordinator with the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. But cases of substance abuse and mental illness are increasing.

Caring for chronic conditions and coordinating care for those conditions between primary care providers and obstetricians is also a concern, Rouse said.

When the experts notice patterns, Virginia’s panel — made up of midwives, nurses, physicians, EMTs, social workers, and more — issues a report and makes policy recommendations, some of which have been adopted.

One recent recommendation included ensuring pregnant women are able to receive substance abuse treatment more quickly.

“It’s a lot more than just medical issues that are occurring that are actually influencing and contributing to those deaths,” Rouse said.

Maryland, which started its maternal mortality review program in 2001, has seen a similar trend regarding substance abuse. Leah Woods, medical director for maternal and child health at the Maryland Department of Health, has been on the project for 10 years.

“When I first came, we had a couple years where our leading cause of death was homicide, so we did a lot of looking at intimate partner violence,” she said.

In other years, hemorrhage cases were responsible for a number of the deaths. Woods said this pattern resulted in a statewide perinatal-neonatal collaboration among the hospitals.

“We added a requirement that every hospital has a written protocol to address massive obstetric hemorrhage, and to be prepared and ready to handle cases that hemorrhage,” Woods said.

Since 2006, California has seen a dramatic decrease (more than 55 percent) in its maternal mortality ratio, as well as a 20 percent reduction in maternal morbidity between 2014 and 2016. The success is attributed to the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative, which works with the state’s review panel and provides hospitals with free tool kits (or “bundles”) on procedures and policies to prevent morbidity and mortality from conditions such as hemorrhage and pre-eclampsia.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists is doing similar work with 18 hospitals around the country through its Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health program. Its goal is to reduce severe maternal morbidity by 100,000 cases and maternal mortality by 1,000 cases over the course of four years.

One way to do that is to supply hospitals with recommendations for emergency management plans and systems. For example, Levy said, having a hemorrhage cart near a mother during and after delivery “makes a difference” when excessive bleeding happens — so does a process for ordering blood quickly, should a patient need it.

“Think about it at a hospital level: If the nurses have one set of guidelines and the obstetrician-gynecologists have a different set of guidelines, and the anesthesiologists have a third set of guidelines, trying to bring that all together at an individual hospital or birthing facility level is very difficult,” Levy said.

“If we bring all of the national organizations together and we create a consensus guideline, that’s then going to be much easier to push out to the individual facilities.”

So far, the program has data from four states, which show a 20 percent reduction in severe maternal morbidity. (Levy explained it’s too early to measure the change in mortality.)

D.C.’s first maternal mortality review panel may lead to updated hospital procedures, but Dr. Bohon said local health professionals and providers can learn even more about keeping moms and babies safe.

“We just have to look from all perspectives. It’s a community-based issue, not just simply what happens at the hospital. It’s what’s happening to these women in their communities,” Bohon said.

“Women’s health matters. Women’s lives matter. And I think it’s important that we realize that yes, (pregnancy) is natural and it’s a normal state of being, but there can be problems. And I think the more we identify the problems, the more we identify the issues, the greater the likelihood that we’re going to be able to get women involved in care, active in their care, participating, asking the questions and get the outcomes that we all want.”

More from the series, ‘Dangers of Childbirth’

Part 2: In US, being black can be hazardous to moms’ health

Part 3: US sees ‘many deaths,’ even after baby arrives