Every Halloween, fake bats flutter through horror movies and paper versions hang from the ceiling at parties in an effort to add to the scare factor.

But a Virginia woman who helps rescue the real ones says bats aren’t creepy, they’re cool.

“Bats are nothing more than upside down dogs,” said Leslie Sturges. “They’re little, but when you look in their faces, red bats are Pekingese, and big brown bats are — some people say — German shepherds. I say chihuahuas.”

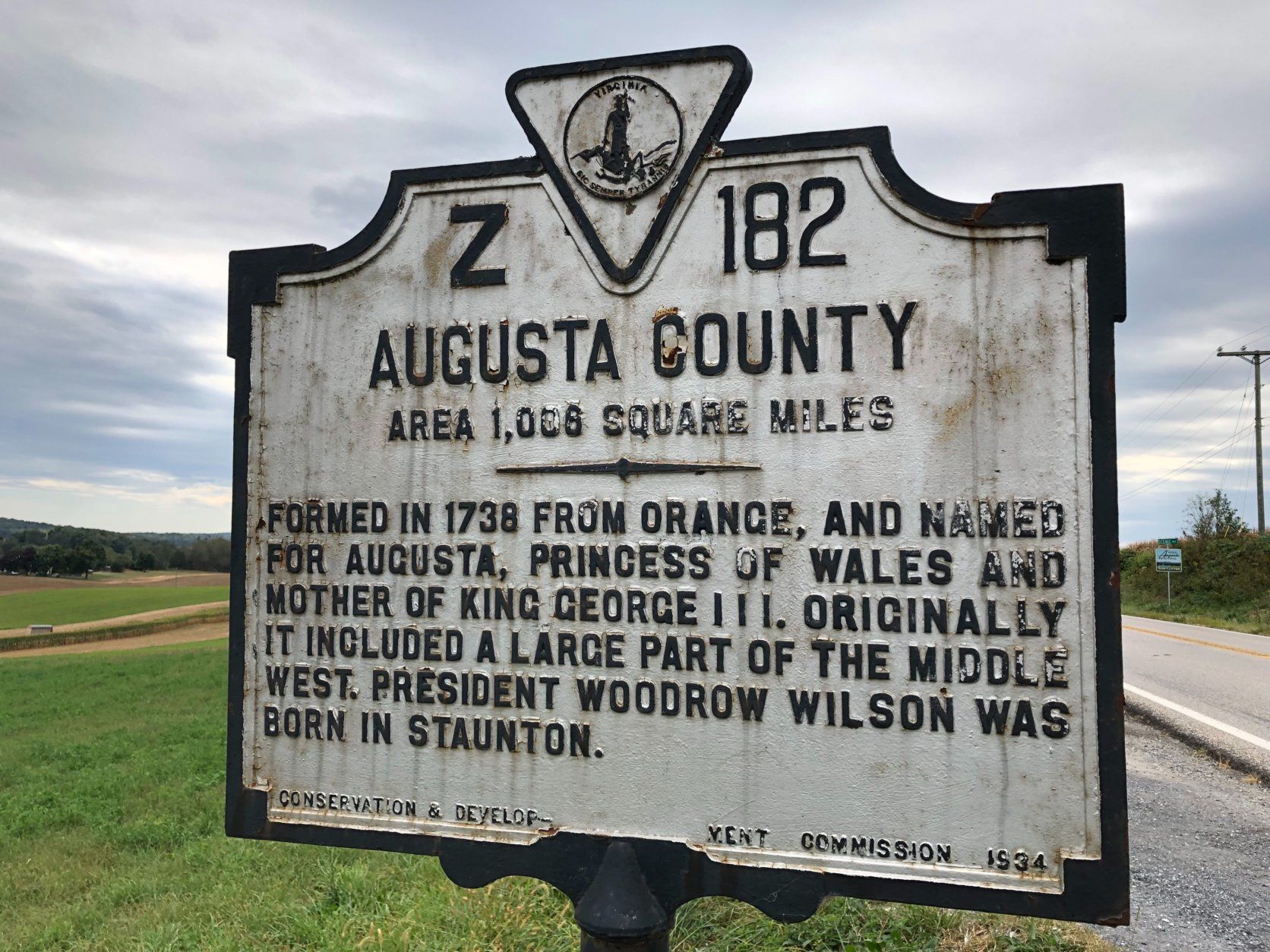

Sturges is president of the Save Lucy Campaign, a nonprofit bat conservation and rehabilitation group headquartered on her property in Mount Solon, Virginia.

Ask her what’s special about bats and Sturges has multiple answers at the ready.

“They’re adorable, and that should count for something. They’re the only mammal that’s capable of self-powered flight. They’re the only mammal with wings — amazing. A female bat that’s lactating eats her own body weight in insects every night. Baby bats start out bald and very dependent on their mothers, and within six weeks they have to be able to fly and start catching their own bugs,” Sturges said.

Save Lucy was founded about a decade ago to help spread the word about white nose syndrome, a fungal disease that has devastated bat populations in parts of the U.S. and Canada.

Little brown bats are now functionally extinct in the D.C. area, said Sturges. “Once upon a time the little brown bat was the most abundant bat in North America, and now it’s on just about every state’s endangered species list in the northeast and mid-Atlantic, because of one fungus that appeared in one cave in the mid-2000s.”

The D.C. region still has about nine native species of bats, the most common being the big brown bat. Adults are usually between 12-16 grams in size, but can grow to as large as 20 grams right before hibernating.

“They have a 13-inch wingspan, so when you see them flying at dusk, people tend to think it’s a huge animal, but a bat is 80% wing,” Sturges said.

The second most common bat in our region is the red bat.

The northern long-eared bat is currently being netted in D.C.’s Rock Creek Park for study by Virginia Tech and the D.C. Department of the Environment.

The free-tailed bat is turning up sporadically in our region, and climate change might be the reason why.

“We’re not sure whether those are accidentals, transients, or whether there’s actually a range extension going on, that the climate might be more hospitable for these southern bats that don’t hibernate but tend to migrate,” Sturges said.

Sturges gets about half of her bats from the Wildlife Center of Virginia, which provides initial veterinary care and then hands the animals over to her for long-term care. The other bats she receives come from other rehabilitators or the public.

She keeps some bats in small, individual cages indoors, and others in a large, octagonal outdoor flight cage. The cage is made of screens, and has a black light inside to draw insects in. It’s a place where injured bats can back in flying mode, and young bats can practice hunting. When animals are ready to be released, panels at the back of the cage can be opened to let them out.

About half of the bats that arrive at Sturges’ sanctuary end up back in the wild. Others that can’t be released but are still expected to have a good quality of life join her education collection.

If you spot a bat that you think might need help, Sturges advises, your first move should be to grab your phone.

“The best thing to do, if you see bats in a weird place, is take a picture — don’t touch them — take a picture and text it to your local rehabber,” Sturges said. “I tell you, we have been able to rescue so many bats since the advent of cellphone cameras.”

If you touch or otherwise come in contact with a bat, the bat will need to be tested for rabies and you’ll need to get rabies treatment, just in case.

“If you never touch the bat, and you use gloves and use a towel and pick the bat up and get it safely contained in a box, we can help that bat. People are doing that, and it’s wonderful,” said Sturges.

She mainly brings her bats to schools and libraries, in hopes of giving kids and adults a glimpse of an animal they’ve probably only seen from afar.

“So few people ever see a bat face. People see shadows with wings in the night sky, and they see horrific imaginary bats in TV and movies,” Sturges said.

Bats usually only have one baby — or pup — per year, and the chance of surviving its first year are 50% at best. Bats can also live for a long time. On average, the big brown bat lives about 19 years in the wild. One little brown bat that was wild but banded, was found to be 34 years old.

Bats are also very smart.

“They have very high social intelligence because they live in colonies and they have to know 300 people in their world,” said Sturges. A large study done in Europe found colonial bat social structure is comparable to that of elephants, crows and humans.

If you’d like to give bats a helping hand, installing a bat box isn’t the best way.

“Bats have a lot of available habitat, so building a bat box and sticking it in your backyard is pretty much guaranteed not to get you any bats in the Washington Metro area,” Sturges said.

“If you really want to help bats, pull invasive plants, plant natives (and) keep waterways clean and clear. We have lots and lots of storm management ponds that maybe could be managed better for wildlife. Bats need open water to drink. Your home ponds are not just for mosquito breeding,” she added.