WASHINGTON — Transportation funding issues are impacting the D.C. region and the nation, and the Congressional Budget Office has some suggestions for easing traffic and finding new money.

New tolls or fees for drivers on interstates and other highways, and changes to how money is allocated for repairs and construction, are among the limited options, the agency said in a report this month.

“Charging for the use of roads could allow for more travel overall by reducing congestion, which occurs in many urban areas during peak periods. That counterintuitive effect occurs because user fees, by diverting even a relatively small number of users to other roads or to another time of day on the same road, can cause speeds to rise sharply, increasing the total number of vehicles that can pass through a bottleneck during peak periods,” a report released this month says.

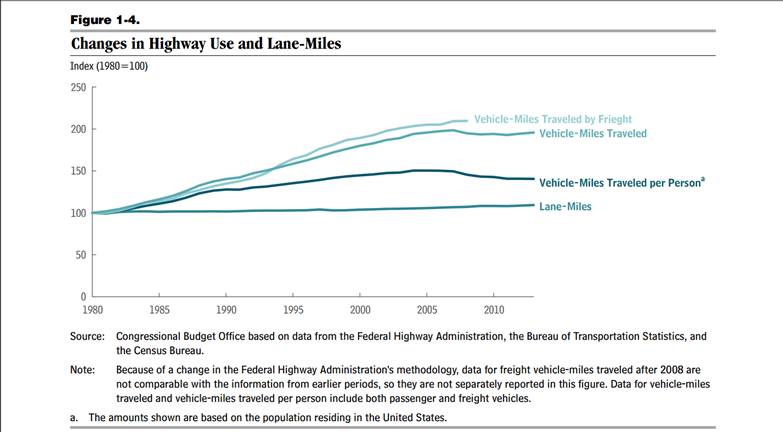

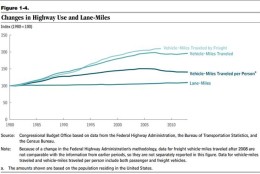

It suggests tolling be allowed on more interstate highways and bridges, or new fees per mile traveled like those being tested in Oregon. Last year, the report estimates the nation’s approximately 4 million miles of roads carried cars, trucks and motorcycles about 3 trillion total miles.

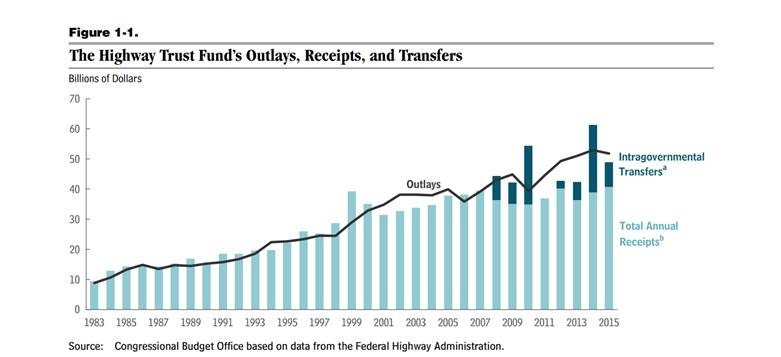

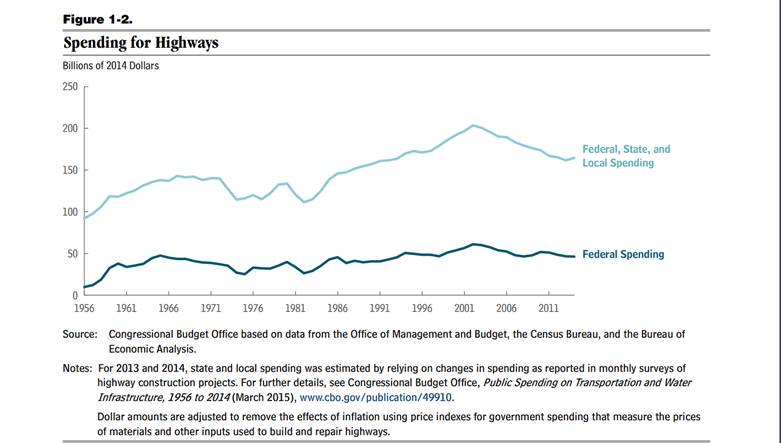

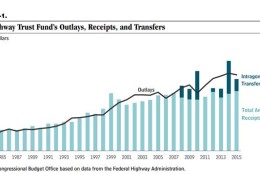

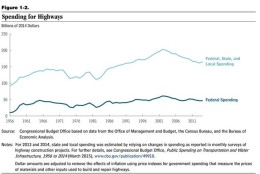

“First, the federal government’s main source of funds for highways — gasoline tax revenues dedicated to the Highway Trust Fund — has been insufficient to pay for federal spending on highways. Since 2008, lawmakers have transferred about $143 billion from other sources to maintain a positive balance in the trust fund. Second, adjusted for changes in construction costs, total federal spending on highways buys less now than at any time since the early 1990s,” the report says.

It acknowledges potential concerns about new tolls or usage fees, including concerns about privacy and a potential burden on lower-income families.

“Moreover, highway users could resent paying tolls if they believed that they had already paid for the roads through gasoline taxes over the years. And technological hurdles may exist: Although the costs of charging drivers are declining with improvements in technology, the costs remain higher than those for collecting revenues through the gasoline tax,” the report says.

The anti-toll sentiment has been expressed particularly strongly in recent months in Washington suburbs like Loudoun and Prince William counties as part of opposition to plans to add tolls for solo drivers on Interstate 66.

“The problem, years ago, was singling out Northern Virginia for special treatment. Now we’re singled out for special treatment again and again and again, and that means more tolls,” Del. Bob Marshall told reporters earlier this month as he complained about a deal to fund a third lane on 66 inside the Beltway by 2020 in exchange for tolls being allowed to begin in late 2017.

But Pat Jones, the executive director of the International Bridge, Tunnel and Turnpike Association, a group representing toll facility owners, operators and builders, says the money has to come from somewhere.

“There are no free roads, your road is either going to be supported by taxes, or it’s going to be supported by tolls,” Jones says.

“It’s easy to look at a road and say ‘there it is, we paid for it,’ but people forget that it needs to be maintained and rebuilt over time.”

Jones compares potholes and other road maintenance to issues homeowners face.

“Even if the mortgage is paid off, you still have expenses to live comfortably in your home,” he says.

The CBO report cites research showing that building new highways in many areas no longer boosts economic activity as much as during construction of the Interstate Highway System, but notes that spending of federal dollars has not shifted to focus on needed maintenance in and around urban areas.

“Research suggests that when new capacity is added to existing roads, the benefits — in terms of reduced congestion and, hence, travel times — diminish over time as the roads become more fully used again. As more traffic uses the new lanes, travel speeds decline toward those that existed before the improvement. A recent study finds that the addition of new lanes is likely to have little effect on congestion within 10 years,” the report says.

“Instead, businesses use more trucking, residents drive more, new people move to the area, and traffic is diverted from other roads to the new lanes. Some of the “induced traffic” may represent additional economic activity, and some may represent economic activity redistributed from other areas. Indeed, in some cases, investments in state and local roads have simply led to the redistribution of existing economic activity from adjoining regions,” it continues.

No matter what happens on the funding side, the CBO expects traffic jams will get even worse unless a recent drop in vehicle-miles traveled per person continues.

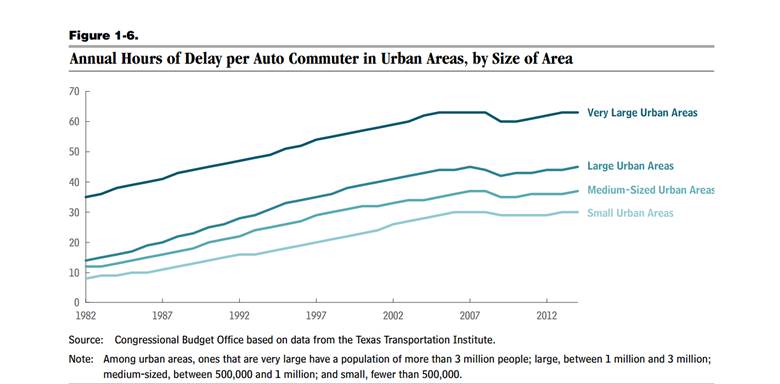

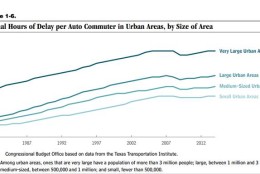

“Delays in urban areas of all sizes have increased substantially since 1982, when such statistics began to be collected, although in recent years, they have moderated because of the decline in travel. Drivers in very large urban areas (defined in terms of population size) experience more than twice as many hours of delay as do their counterparts in small urban areas. In percentage terms, however, delays in small urban areas grew even more than those in very large urban areas. The Census Bureau projects that the United States will add about 100 million people to its population by 2060, suggesting that congestion may become more problematic in the future,” the report says.

In Maryland, the Intercounty Connector toll road, and in Virginia the 95 and 495 Express Lanes have opened in recent years, with ultimate funding expected to come through tolling.

Jones says even if there are people who avoid the tolls, it at least offers a choice.

“Ultimately, every organization like a freight hauler or an individual has to make their own choice about the trade-off between time and money, and we believe that most people place a high value on their own time,” he says.

In Loudoun County, elected leaders argue people have made that choice: they do not want to pay $6.20 per day each way to ride the Dulles Greenway to and from the Dulles Toll Road only to pay more tolls to reach Reston or Interstate 66.

“People along the Toll Road corridor, along the Greenway have felt ignored,” Broad Run District Supervisor Ron Meyer told WTOP this week.

The county is backing a new road parallel to part of the Greenway by 2020.

Del. Jim LeMunyon, who has now signed onto the I-66 toll plan inside the Beltway following the deal to construct a new eastbound lane, still wants to keep tolls from expanding to other roads.

“We’re just going to stop this, it just can’t keep going on forever,” he says.

A bill in Virginia’s General Assembly that has the support of Gov. Terry McAuliffe’s administration would outline where future tolls would be allowed.

The CBO report acknowledges that since technology is only now reaching the point where all-electronic tolling can avoid slowing down traffic and provide up — to-date variable pricing, any widespread tolling changes could require significant trial and error.

However, when the right balance is struck through tolls or travel distance fees, there can be significant drops in the need for future road widening as drivers think harder about whether each trip is really needed.

“Currently, only about 7 percent of the Interstate System is composed of highways with tolls. Interstates, which are typically the most heavily used roads, would yield the greatest benefits from such pricing. The revenues gained from tolling on Interstates could be used to make repairs, expand capacity, or substantially renovate the Interstate System. Or, of course, lawmakers could allow those revenues to be used for other purposes. An alternative approach would be to encourage private companies to own or operate Interstate highways, which would allow them to charge tolls or set prices that corresponded with the amount of congestion at a given time,” the report says.

The concern would be that more people using side roads could increase the costs of maintenance there.

The report says public-private partnerships like the 495 and 95 Express Lanes and the planned Interstate 66 HOV or toll lanes between the Capital Beltway and Gainesville often provide more money up front for states, but appear to end up less beneficial than the initial boost in the long term.