WASHINGTON — It sure felt like spring for a few days around Washington, and indeed, it may be meteorological spring (more on that later), but Wednesday’s cold, blustery winds and scattered flurries are a reminder that it’s actually still winter.

The National Weather Service has issued a Winter Weather Advisory for the WTOP listening area from 10 p.m. Thursday to 10 a.m. Friday.

From now into the weekend, look for below-average temperatures and the likelihood of more measurable snow. But will it be a “plowable” snow? It’s late winter, so the answer is complicated.

The system that will affect us hasn’t formed yet, but it will result from energy associated with the northern branch of the jet stream (a source of cold, dry air) and the southern branch of the jet stream (a source of moisture).

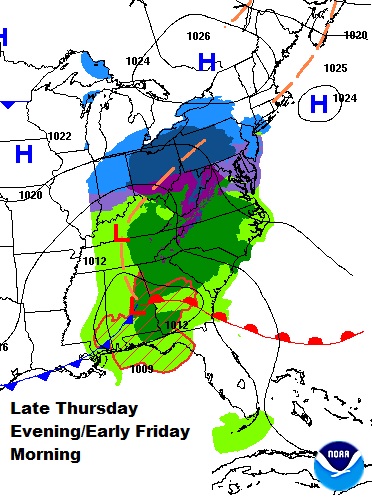

The pieces of energy will form an area of low pressure at the surface that will scoot to our south, as opposed to Wednesday’s low pressure system, which passed up toward our northwest — keeping us in the “warm sector” until the cold front went through and drying us out before we got too cold. This low will intensify as it heads towards the Mid-Atlantic coast, and bands of precipitation will move over the area starting Thursday evening through Friday morning.

“How much snow will we get?” is a difficult enough question in the dead of winter. This time of year, the question is not how much will we get, it’s “How much will we end up with?” because of the issue of melting.

The temperatures in the clouds, the temperatures on the way to the ground and the temperature of the ground itself all come into play. In fact, one reason snow is even on the table at all, instead of just cold rain, is that a lot of the precipitation will fall at night, when we won’t have the benefit of sun angle to keep the ground and atmosphere warm.

Sunshine Thursday morning will help keep the ground thawed and high temperatures close to 40 degrees. Clouds will come in before sunset; clouds keep the sun’s energy from the day from radiating back out to space. That energy gets “reflected” back to the ground to keep it thawed. When the snow first arrives around midnight, the initial rounds of snowflakes will dry up and/or melt before evaporating.

Both processes take heat out of the air and moisten it, allowing more snowflakes to get closer to the ground. Eventually they do. In the dead of winter, they would start accumulating immediately on all surfaces, but not in this case. Here, the most likely areas for sticking will be grassy areas and then pavement and sidewalks.

You may ask yourself this: If there’s melting, how can it stick? It’s a simple comparison of rate of melting versus rate of accumulation. In areas where it is snowing literally faster than it’s melting, you’ll see accumulation on the ground. Without the sun’s energy Thursday night, the melting won’t be as quick as it will be during the day on Friday.

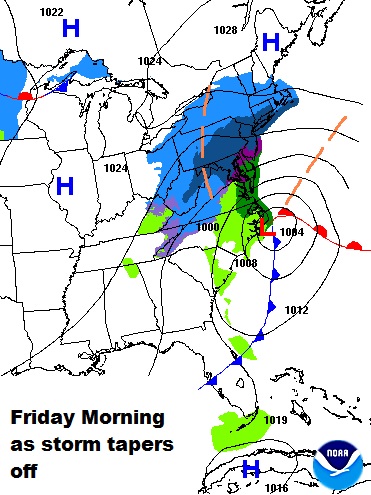

As Storm Team 4 looks at all the ingredients, factors and qualifications, and how they all work together, there’s a belief that many folks could wake up to one to three inches of a slushy, wet, half melted snow Friday, but mostly on the grassy areas. That means the plows may not really be needed for shoveling — only road treatments. And then as the snow ends Friday morning and some sun comes out in the afternoon and temperatures get close to 40 again, even more of the snow will melt away.

This is a scenario in which the largest snow amounts will likely occur close to the rain/snow line. Right along that line is where the snowfall rates are highest and where the most melting is happening in the atmosphere — in turn resulting in the most cooling with height, and thus more snowflakes making it to the ground before melting on the ground.

In a typical winter storm, the ratio of snow to rainfall equivalent is 10:1; in other words, the moisture that would make for one inch of rain would produce 10 inches of snow in a highly idealized environment. This storm will likely have less than that — probably 5:1. That’s another reason it will be very wet and slushy, as opposed to dry and fluffy (the higher those ratios, the higher the fluff).

Okay; the next obvious question is, “Is this winter’s last gasp?” As mentioned before, this is part of a pattern keeping the cold air in the East and the warmer temperatures in the West. The northern branch of the jet stream will send a “clipper”-type system through on Saturday that may produce a few showers of rain and wet snow.

But then high pressure will build in for the second half of the weekend and flatten out the jet stream, keeping the cold air from flowing down from Canada. More sunshine, too, will mean moderating temperatures back closer to our average for Sunday. The arctic air will be trapped in the Arctic.

By the middle of next week, a ridge of high pressure looks like it will set up shop here in the East, and that means temperatures possibly well above average for several days next week. Many computer models suggest that ridge will break down, so it could get chilly again before the end of the month.

But every day we go through March because of the higher sun angles, it gets harder and harder to get snow and ice. It’s not impossible (as we know from blizzards like 1993), but it’s unlikely. So short of a fluke, Friday’s snow may be the last we see this season.

Lastly, what is meteorological spring? It’s simply March 1 through May 31. Because the actual seasons vary so greatly by exact times of solstices and equinoxes and leap years like this year complicate matters even further, meteorologists find the easiest way to keep the books organized is to keep seasons at the beginnings and endings of certain months.

An excellent, detailed explanation can be found here.