WASHINGTON — From youth sports to the top level of every game, injuries are an inevitable part of sports. But when the skin is broken and bleeding needs to be stopped, there are competing needs of finding a sterile way to protect the wound and trying to stop the bleeding as quickly as possible, by any means possible, to allow the athlete to return to action.

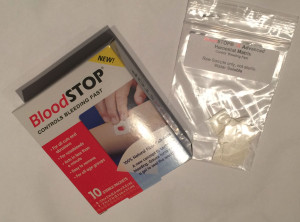

One company has developed a product that strives to achieve both goals at once. Originally designed for and used in military and medical applications, BloodSTOP is a hemostatic, woven matrix of fibers made from plant compounds that looks like a thin strip of gauze. But when applied to an open wound, it absorbs the blood and adheres to the surface to stop bleeding, forming a protective gel layer in less than a minute while the body begins to coagulate underneath.

“All you have to do is apply it directly to the wound site and hold pressure for 30 seconds,” says Lason Magallones, who spent 21 years working in the Air Force cardiopulmonary laboratory before going into the private sector to work for LifeScience. “Then wipe away whatever doesn’t turn to liquid or gel form.”

A sample used on wet skin binds and solidifies, like a piece of paper mache. An hour after application, the remaining bandage can be washed away with water, leaving the wound to heal.

Cut men in boxing will commonly use collagen sponges like Avitene to try to coagulate an open wound. Sometimes they will even use diluted adrenaline on the surface to help constrict blood flow. While these methods help to get the fighter back in the ring more quickly, neither are about helping the wound heal well in the long term. The ability to achieve the same results or better with a product made of cotton is promising for any athlete, whether it be a youth soccer player or LeBron James in the NBA Finals after cutting the top of his head on a piece of camera equipment.

BloodSTOP has yet to break into the sports world, though that seems to be its ideal application outside of a military setting.

“The initial creation of this product was to stop bleeding for everyday injuries, nose bleeds, head-butts,” Magallones says.

One could see how the application might be more crucial for hikers or rock climbers, perhaps stuck halfway up a mountain somewhere, a good distance over tough terrain from getting back to civilization.

There is also the BloodStop iX, a higher density version of the product intended for surgical procedures and hospital use. It is not yet approved for use in the U.S. until it achieves certain testing benchmarks, but is being used abroad in China and Europe already. It was also used in the field by a police officer in Florida earlier this year to treat a gunshot wound to the face.

Successful applications like that ask the question of whether or not the product could also potentially offer hope for those with hemophilia, a condition that keeps blood from clotting, making almost any open wound on the knees, elbows or ankles cause for a hospital visit. For children with hemophilia, athletic endeavors pose a constant risk, especially contact sports. But with a product that does the clotting for you, the pressing concern is not as constant.

“I think there are a lot of issues out there,” says Magallones. “People having heart attacks, putting stents in, using anticoagulants to make their blood thin.”

But in professional sports, where the cost is less of an issue than on a youth team, and where there is such a premium in returning top athletes to the game without missing any time, this could be a major development coming soon.