Within the very narrow parameters that the Washington Nationals allowed themselves to operate and improve their team at Major League Baseball’s trade deadline Wednesday, they did so.

The Nats acquired three relievers, each with experience closing, two with years of team control beyond 2019, all without giving up any of their top prospects.

Like so many other Nationals decisions over the past few years, Wednesday’s transactions look good enough on paper. In a vacuum, the team addressed a specific need and should get immediately better. Mission accomplished, right?

Right?

As has become tradition in Washington, the Nationals found a way to make overtures at addressing their biggest need without making the most impactful move in front of them.

As they did in 2015, they went looking for relief help on the cheap, both in terms of monetary and personnel cost (and we all know how that ended). Worse, the Nats watched the team they were playing — the team they are chasing — which already had a better bullpen (ninth in MLB in ERA), improve its relief corps more impressively and still at a fairly low cost. Then they lost to them.

With a chance to win a series at home against the Dodgers and Braves, the Nats had the opportunity to announce their presence with authority and assert themselves in the discussion of serious National League contenders. Instead, the Nats did what bad teams do.

They lost the two potentially competitive games to open the set against LA, then salvaged a good-on-paper-and-for-the-run-differential blowout Sunday with their best remaining starting pitcher on the hill, in a matchup they absolutely needed to win.

They did the same against the Braves, just in reverse order, winning the one clearly favorable matchup behind Patrick Corbin (thanks to Anthony Rendon’s grand slam) only to lose the next two.

In truth, the Nationals made only one statement this week — the same one they’ve been making for the better part of the last decade — with their decision at the trade deadline: they’re trying to compete today while keeping an eye on tomorrow.

That’s a statement that sounded good back then, but the lack of results have started to pile up in unsightly heaps of postseason disasters or regular season-flameouts, missing October entirely.

The Braves are anything but infallible; the Nats have split the 12 games against them thus far. Atlanta is a good team, but not on the level of the Dodgers, Yankees or Astros (even before adding Zack Greinke).

The NL East should be a winnable division and easily could be with a better bullpen. It could still be, with some additional regression or batted ball luck, but the Nats are still running with a lot of question marks at this point.

They had the chance to add some more solid answers Wednesday, but chose more of the same low-risk, low-reward types of acquisitions as the Jonny Venters and Fernando Rodney signings in getting Daniel Hudson, Roenis Elias, and Hunter Strickland.

But, hey, that’s what they got. Will this haul makes them any better? Yes.

Well, probably.

If Hudson stays healthy and continues to produce at his current rate, he’ll be an upgrade over the DFA’d Michael Blazek and Javy Guerra, though there’s reason to worry that his 4.21 FIP suggests some regression back toward the 4.49 ERA he has put up in his career before this year (3.00) since moving to the bullpen. He’ll strike out a batter an inning; he’ll walk almost half that. He’s also a two-time Tommy John surgery survivor.

Elias is solid but unspectacular, which you’ll note is, generally, an improvement on the state of affairs. He’s another converted starter, but only in his second full season as a reliever. While his hit rate is about the same and his strikeouts are actually up from a 2018 that saw him post a 2.65 ERA, he’s nearly two points worse this season thanks to a home run rate that has skyrocketed.

He’s also got some bizarrely severe reverse splits this year — righties are slashing just .182/.238/.341 while lefties are crushing the southpaw at a .353/.441/.549 clip. We’ll see which version of Elias the Nats get, but with the expectation they’ll send out one of their two incumbent lefties to clear space, it’s unclear how Elias fits in.

Strickland is a total flyer. He’s been hurt almost all year, but even when healthy hasn’t regained his pre-2018 form. He’s got a lively natural arm, but we’ve seen up close and personal all that’s done for him in the playoffs. Given the history that set of confrontations sparked between Strickland and the Nationals, it’s hard to envision him wearing a Curly W regardless of Bryce Harper’s current status.

But the larger point is that Daniel Hudson and Roenis Elias and Hunter Strickland are not Shane Greene and Mark Melancon. They are not the premiere, high-level back-of-the-bullpen guys who were available Wednesday, who the Nationals had reported interest in, and who ended up in the opposing dugout instead at the deadline.

The Nats were limited in prospect capital by their decimated farm system, but they also limited themselves in their thinking.

Nats had significant limitations going into the deadline. They weren’t going over the luxury tax, so they couldn’t take on much money. They weren’t going to trade one of their top prospects for a reliever w/ limited control. Didn’t acquire the biggest names, but got better today.

— Dan Kolko (@masnKolko) July 31, 2019

Those limitations were self-imposed — a decision made intentionally by management/ownership, not because of some rule by which the club is required to abide. It’s a stance to sacrifice the quality of the present team with hopes of improving it in future years. It is a stance the Nats have often taken at the deadline, with little success in their past future years (like, say, this one) to show for it.

Saying that the club wasn’t going to part with their top prospects was, again, a choice. It’s not the one the Astros made, going out and improving an already formidable rotation by adding Zack Greinke. It’s not one the Braves even had to make, it turns out, in getting both the reliever that helped the Nats make their playoff push in 2016 as well as the one they reportedly coveted this year, all without giving up a Top 10 prospect.

Those two teams — the Astros and Braves — have found ways to win their respective divisions (and lead them again) while continuing to develop their farm systems for future years, giving them the flexibility to make such moves.

“The fact that we gave up nobody in our top 20 prospect list was important to us. We stayed under the (competitive balance tax), which was important to us,” said Rizzo. “But most important was that we’ve improved our baseball team with three really good relief pitchers, two of them that we control for the long haul. And it shows the guys in that room that we appreciate how we’ve been playing, and we see you, we believe it, and we’re all in it for the long haul.”

If you listen, you can hear the organizational priorities. Not giving up prospects; not spending into the luxury tax; getting pitchers for more than this year. None of that equals winning this year. By “the long haul,” Rizzo may well have meant the pennant race this fall, but that’s not what he said. You could be forgiven for thinking that this was another move that wasn’t really so much about winning now.

Meanwhile, the Braves also made their moves — better, stronger moves — without giving up top talent. They were willing to take on more salary, and they also got two pitchers they control for an additional year.

About the prospects — they aren’t worth anything to your current club unless they can contribute today (no) or be traded as assets (possibly — certainly, teams were asking). Rizzo may value his own prospects, but outside of a select few, it seems not many other teams do anymore. Perhaps the Nats can mold some of them into serviceable big league talent. Though their track record, particularly with pitchers, has been more than lacking.

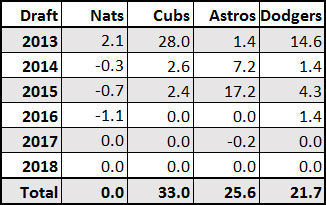

Since selecting Stephen Strasburg in 2009, no pitcher the Nats have drafted has accrued more than the 1.3 career Wins Above Replacement of Matt Grace while wearing a Curly W. They’ve had success in the international signing market with Juan Soto and Victor Robles. But the combined Major League WAR of every player signed from the Nats draft classes since 2013, whether for the Nats or another team? As Dean Wormer put it, zero point zero. And there’s not much help on the way.

Compare that to some of the other consistently successful clubs around the league.

The Nats continue to try to have it both ways, and increasingly end up with neither. They refused to deal Harper at the deadline last year (which might well have gotten them under the luxury tax in 2018, helping them avoid all this current mess), only to fail to re-sign him. If you consider that a positive, in that not landing Harper might help them re-sign Anthony Rendon, you have to consider the very real possibility that re-signing Rendon may not happen either, especially if you listen to him.

At some point, without a foundation of young talent, a team has to accept that it’s worth the risk to push its chips to the middle. Ask the Kansas City Royals if they regret giving up Sean Manaea for Ben Zobrist, who pushed them to the 2015 title.

With as many draft misses as the Nats have had, they’ve also missed chances to restock in years where they couldn’t compete. They refuse to take on salary that might ease the prospect burden of an acquisition.

All of that has led them to an organizational spin cycle in which they don’t have prospects they’re willing to trade or the financial flexibility at the deadline to put their best foot forward toward actually winning a title, only to find themselves in the same position once more the next July.