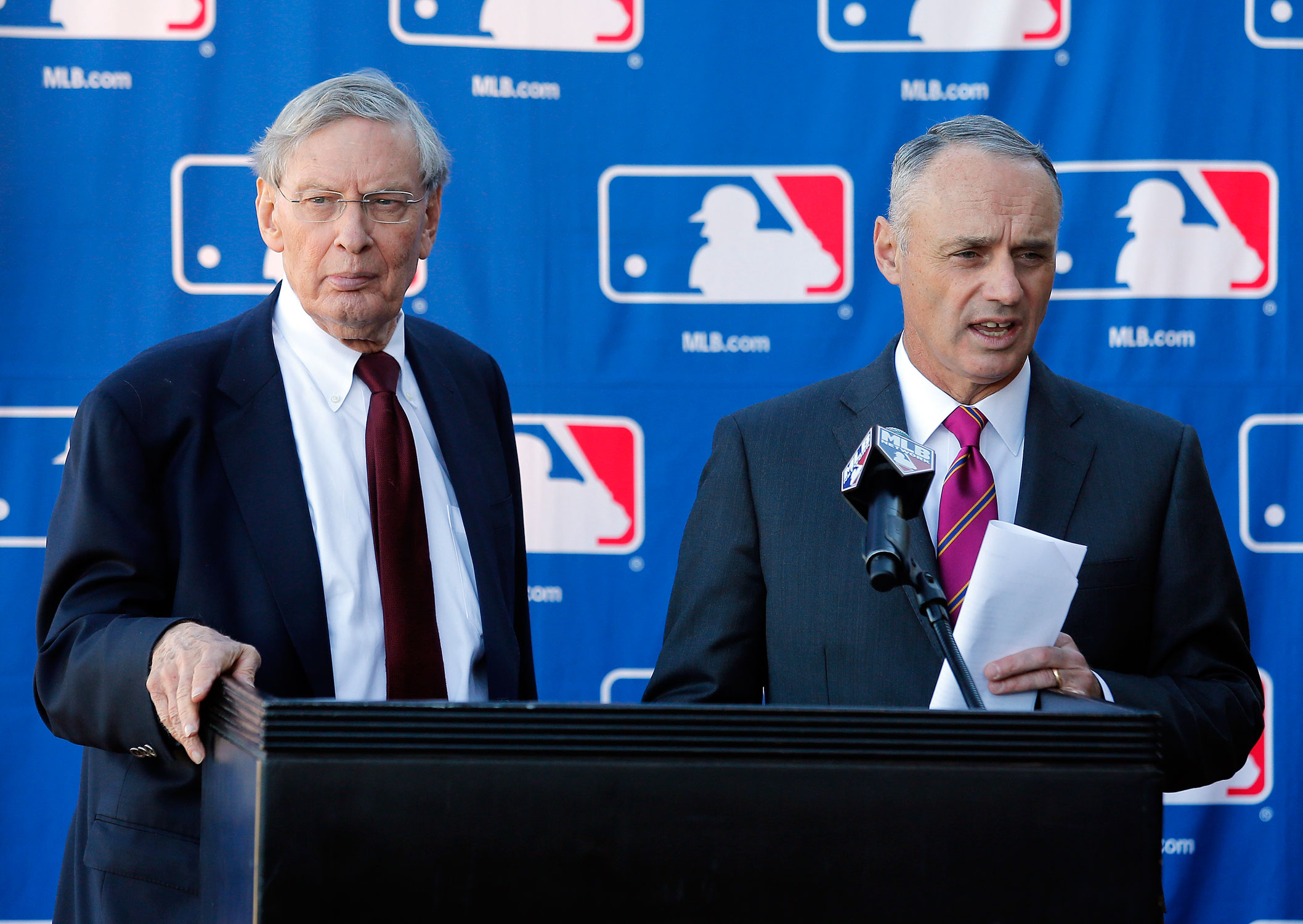

WASHINGTON — It’s been a while since we’ve talked. But Mr. Manfred — Commissioner … Rob … can I call you Rob? — what are you doing?

You’ve floated a number of potential rule changes and other ideas in the past few days, most of which have been set forth in the name of speeding the game up. These proposals — pitch clocks, eliminating the actual pitches thrown in intentional walks, putting a team in Las Vegas — are just that: proposals. Lashing out as you did, at the players union for not automatically agreeing to your ideas, feels like a massive overreaction and that you’re not doing the most important thing you can do in your position, which is to listen.

It feels like you’re not talking to people who actually, you know, like baseball. The ones who actually watch baseball. The ones who play baseball. The ones who make up your core constituency. We’ve reached the point where I’m starting to wonder if you even watch the game you preside over.

Before we get into the rules, let’s talk about Vegas. The idea of professional baseball in Las Vegas is terrible for a host of reasons, not the least of which is the fact that it is already terrible in practice. The Las Vegas 51s — the Triple-A affiliate of the New York Mets — have ranked no better than 13th in the 16-team Pacific Coast League in attendance since 2009, drawing fewer than 5,000 fans per game in each of those seasons. This despite playing in the 28th biggest city in the country. Those who travel to Las Vegas are indulging in entertainment on the opposite end of the spectrum from baseball. The people who live in Las Vegas have pretty clearly displayed over the past decade that they have little interest in baseball.

The scalding summer temperatures make the experience a miserable one for players and fans alike, which would no doubt force the construction of a retractable roof ballpark that would be mostly (if not entirely) closed. We know this robs fans of one of the best parts of the game — the outdoors — because cities like Minnesota, Chicago, Boston and New York put up with weather swings of all sorts just to play under the sun. If they put a roof on Wrigley, there would be riots. That’s all more important than any perceived hypocrisy of installing a franchise in America’s gambling capital all while you refuse to allow Pete Rose into the Hall of Fame.

But let’s get back to the rules. I’m hardly a traditionalist: I’m all about innovation and learning how to exploit the small margins of the game to incrementally increase your chances of winning. I’m in favor of the designated hitter in both leagues, considering that no pitcher bats in college or even the minor leagues anymore until they reach Double-A, and even then only if they are a member of a National League affiliate playing against another National League affiliate. But that’s a discussion for another time. The point is, changes are alright, so long as they are practical.

Baseball’s everlasting beauty lies in its idiosyncrasies. Just like a deck of cards, which will appear in a different order nearly every time it is shuffled, the 27 outs on either side of a baseball game will unfold in new and different ways every time a game is played. Each out must be earned, each piece of strategy employed with the implicit risk it carries.

A defensive shift (like the ones you talked about outlawing) is a choice, one that can backfire in any number of ways. So is an intentional walk. While there are many cases where it shouldn’t be used from a strategic standpoint, the chances that the execution might fail are minute, but very real. Do you not see that? Do you not feel your eyebrow raise, your pulse quicken a little when you see an intentional ball float a bit too high, or too low or too close to the plate?

There were 932 intentional walks in baseball last year. That may sound like a lot, until you realize there were 2,428 games played, meaning there was one intentional walk roughly every 23 innings. Saving 45 seconds every two-and-a-half games isn’t a real issue. So even if this rule change does happen, as it appears it will, it shouldn’t actually help shorten games perceptibly.

Besides, intentional walks give the fans a chance to boo, which is just as valid an emotional response as a cheer. They build tension. They are also an actual part of the game.

If you are looking for substantial changes to tighten up the downtime, there are ways to do this without affecting gameplay. A hard time limit on replay reviews — say, 90 seconds — would be enormous. If you can’t overrule the call in that time, it stands. A stricter enforcement of the pre-existing batter’s box rules, penalizing players for the seconds they waste between every single pitch, would have a far greater cumulative effect.

But the larger question here is why you think that speeding the game up should be baseball’s top priority. Who told you that? Did baseball fans — you know, people who actually like and watch baseball — tell you the game was too slow? Or did you hear from some market research that millennials don’t have the attention span for the game? If it’s the latter, do you really think dicing out a few minutes of downtime will be the difference in converting them into fans?

One of the greatest parts of going to (or even watching or listening to) a baseball game is the space interspersed into the game action. It allows for conversation, for time to take a bite of your hot dog or a sip of your beer. For the restless, technology addicted among us, it’s a chance to check your texts, or emails or social media. The concept that fans are prisoners for the duration of time from when they first sit down until the last out is made is not only facile, it’s insulting. You can show up and leave, tune in and tune out, whenever you want. You don’t have to be 100 percent transfixed on every pitch and every action between them.

But you can be, if you choose. You can allow the ballpark to be an escape, one of the few available to us anymore. You can shut out the world and let the sights, smells and sounds of summer flow through you. The absence of a clock rigidly tracking every bit of action is what makes baseball different from other spectator sports.

It’s what makes it baseball.

So hey, you know, keep thinking of new ideas, but maybe consider how much they actually improve the game — if at all — before demanding that everyone go along with them. Maybe stop excoriating the players association for not automatically saying yes, considering that they’re the ones who actually play the game. And maybe take the time to watch a game down with the fans, a hot dog in one hand and a beer in the other, sunshine beaming down on your face. It’s really not that bad. I promise.