Facing rising gun violence and intense scrutiny, it’s not an easy time to be a police officer. To provide additional support, the police department in Prince George’s County, Maryland, is hoping to more than triple its number of five volunteer police chaplains to serve its nearly 1,500 officers.

“Officers get to see the best and the worst there is in society. Unfortunately, when you watch movies you see cops shooting people, the next day they’re drinking coffee and everything is just fine. That’s not the way it works in real life,” said Claudio Consuegra, Prince George’s County police’s lead chaplain.

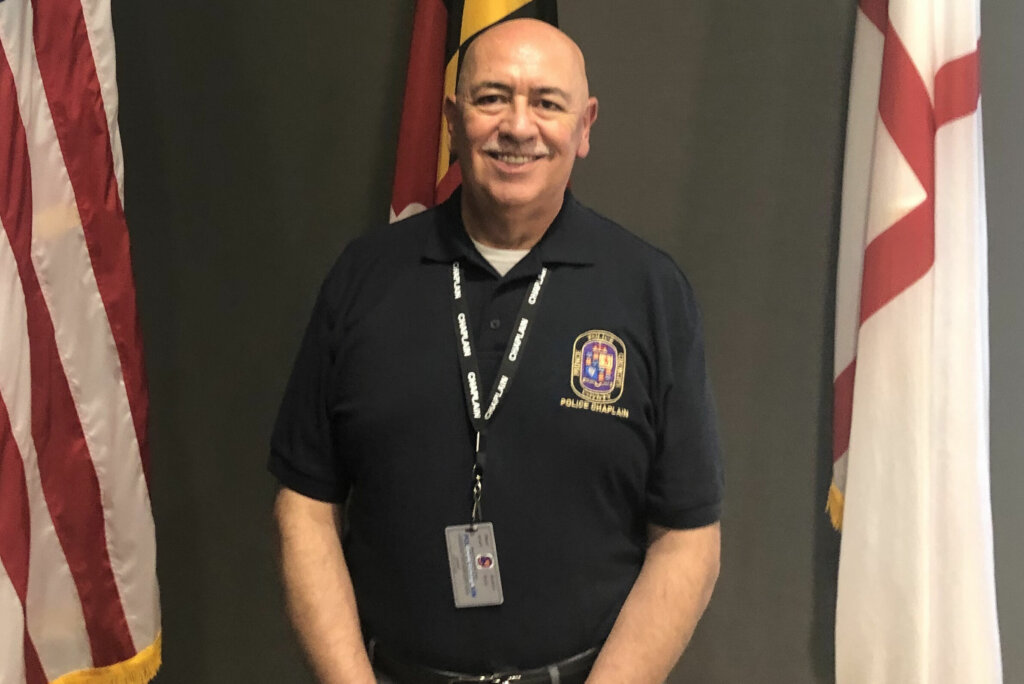

Over 35 years, the past 10 in Prince George’s County, Consuegra, a pastor with the Seventh-day Adventist Church, has volunteered as a police chaplain and is helping lead the effort to recruit more volunteer pastors.

“We’re looking for Christian pastors, priests, Jewish Rabbis, Muslim Imams, anyone who has specific training in a faith-based religion,” Consuegra said.

Like all area police departments, Prince George’s County police has mental health therapists, counsel officers and peer support to help officers cope with the stress, anxiety and trauma that come with the work of public safety.

Consuegra, who has volunteer as a police chaplain in 12 different agencies in six states, said the spiritual element brought by chaplains can also be a powerful healing tool for officers who see and experience things others never do.

“Not only what I find, but research has shown that those who deal with trauma from the spiritual point of view tend to heal faster and better than those who don’t deal with spirituality at all,” said Consuegra.

Capt. Susan Smith, assistant commander of the Beltsville station and a 26-year veteran officer, is in favor of expanding the chaplain program, having witnessed valuable contributions that Consuegra has made in the emotional and spiritual well-being of her officers.

Smith is particularly pleased with his riding along with officers in their cruisers, giving them the chance to talk about their worries and concerns.

“I think it’s a great idea, it gives the officers a kind of a safe place to open up … you need a safe place where you can offload, and I like the idea of him riding in the cruisers because you have privacy and the chaplains get a firsthand experience of what the police officers go through … it’s one more piece in the wellness puzzle,” said Smith.

When officers complete a day’s work, which could include traumatic events such as serious traffic crashes, violent crime or split-second decisions involving life or death, officers benefit by talking about their experiences and the impact on their personal well-being.

Consuegra said he has no magic wand to wave and it’s not necessarily the words he speaks that matter most.

“We mostly listen to what they tell us, but then we can share with them things that they can do to help them process through what they’re going through,” said Consuegra.

The police chaplains are also training in critical stress management.

“We want to have chaplains who are committed to this ministry,” said Consuegra.

Consuegra made clear that police chaplaincy is not about trying to drum religion into anyone.

“We as chaplains are not here to proselytize, to convert anyone, but rather to help them get in touch with their spirituality, whatever they understand it to be,” said Consuegra.

While the department would like to have at least two chaplains for each of its eight district police stations, Consuegra said 25 or more could be needed as the program expands in the years ahead.