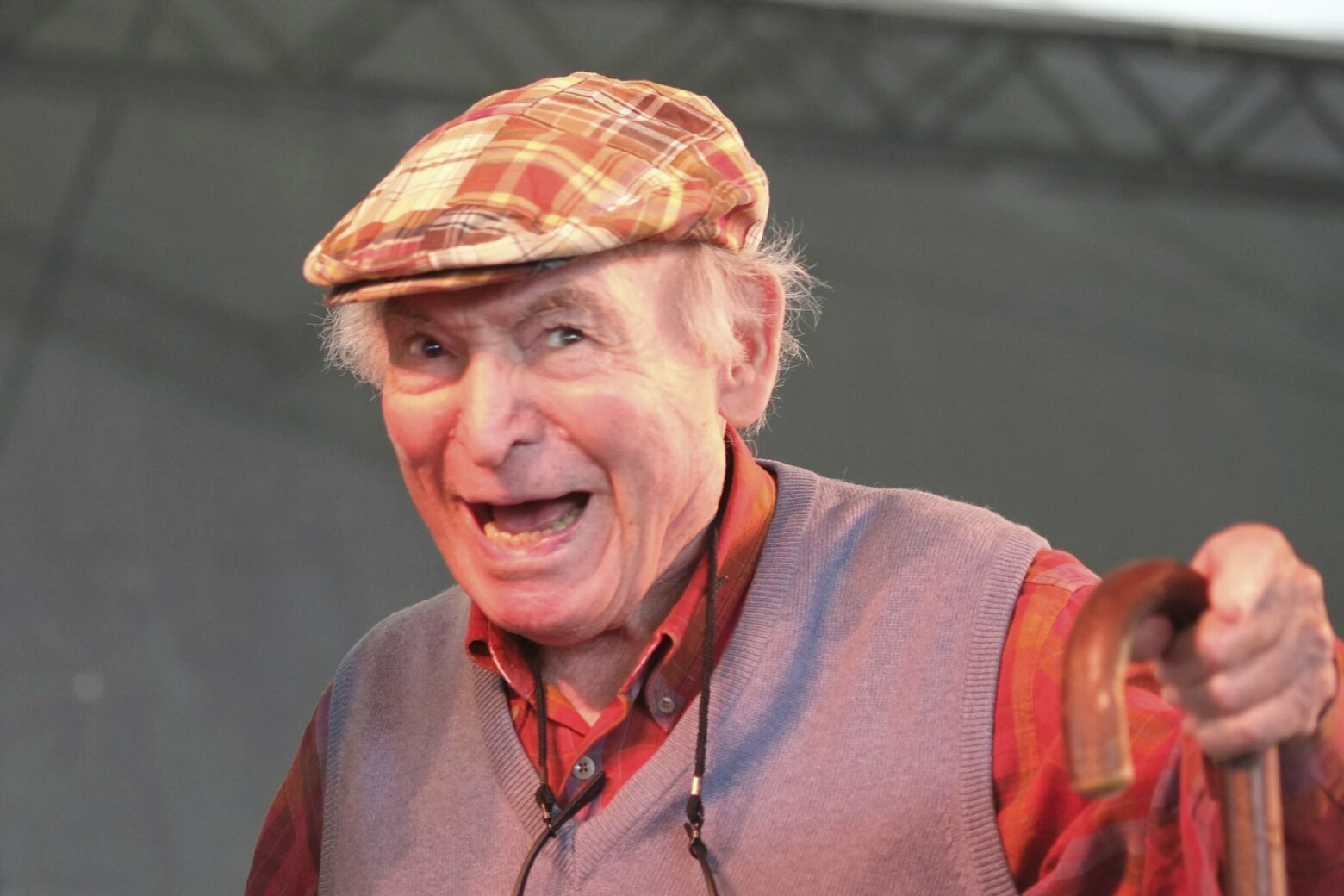

George Wein, the impresario of the Newport jazz and folk festivals who died Monday at 95, essentially invented the American outdoor multi-day music festival, so if you’ve been to Coachella or Bonnaroo, or read about Woodstock or Monterey Pop, you’ve been touched by the idea he brought to life all those years ago.

The thing I remember best about him, though, was the simple, quiet, persistent way he lived his life — an ethos that anyone in any field of endeavor can learn from.

When George caught the jazz bug, he began as a piano player, and he wasn’t a bad one (he eventually made 12 albums). But he’d be the first to tell you — in fact, he said so in his memoir, “Myself Among Others” — that there were plenty better than him, and when he saw up close how some great players were living, he knew he’d have to find something else to do.

That’s when he opened the Storyville nightclub in Boston; the Newport couple Elaine and Louis Lorillard, looking to shake up the boring Newport society summers, wanted to have a jazz version of summer festivals such as Tanglewood and were put in touch with him, and the rest is history.

The first Newport Jazz Festival was in 1954; five years later, folk was such a popular music that, while George considered having a folk day at the jazz festival, the idea quickly outgrew its bounds, and an entire companion festival was born.

Through it all, there was George — making sure the bills were paid, creating and keeping the schedule, arguing with vendors, complaining to the press and keeping an eye on the weather. Because you can’t have a music festival without musicians, but you can’t have one without someone taking care of all of that too. And he did it for the many other festivals he created over the years, perhaps most notably the Jazz and Heritage Festival in New Orleans.

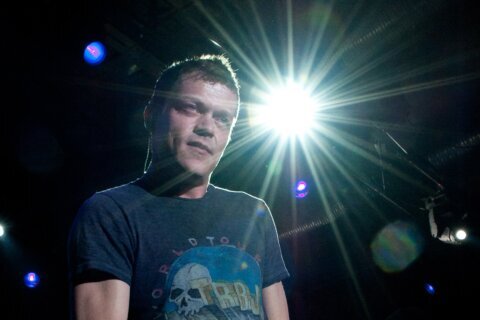

In his later years, he handed off the running of the festivals to deputies, but he prowled the backstages at Newport, keeping an eye on the proceedings onstage and off. The folk festival referred to Wein as “our North Star” in their announcement of his passing, and folk festival producer Jay Sweet told me frequently that “What will George think?” is never far from his mind when making a decision.

But like I said, you don’t have to know anything about the music to draw inspiration from his life.

When Joyce Alexander, a Black woman with a degree in chemistry, married George Wein, the Brockton, Massachusetts, piano player, in 1959, their marriage was illegal in 19 states. And while George would be quick to say he wasn’t on the front lines of the Civil Rights struggle, the two of them (Joyce died in 2005) fought their battle in their own way — by continuing to do their work, and continuing to live with, and insist upon, dignity.

“That’s how I did my fighting,” he told me; “by just being there.”

I spent a day with George Wein in New York in 2009; those hours of interviews became the basis of my book on the history of the Newport Folk Festival. And the spark — the reason I kept working on the book for eight years before it was released — came from the story he told me about his efforts to start a festival in New Orleans.

The city fathers invited him to come start a festival on multiple occasions in the 1960s, but they always fell apart over the question of race — first because George informed them that biggest names in jazz wouldn’t play for segregated audiences, later because they found out about Joyce. They eventually had someone else run the festival for the first year, but when that foundered, they came back to George. “And they treated Joyce like a queen,” he said.

George Wein was one of those people who smiled with his whole body. But he turned serious when he explained that, throughout the process, he knew exactly what he was doing.

“I lived an integrated life,” he told me. “And everywhere I went, I think, I left my mark with people. I never wanted to be a rebel. I never thought I was doing anything different by marrying Joyce. I wanted the same kind of respect my father had as a doctor. I wasn’t going to live an outsider’s life. I was part of society. And to this day I still am. And that’s why I’ve lasted all these years, I think.

“I don’t compromise, but at the same time, I don’t tell anyone else they’re wrong. They have to find out that they’re wrong.

“And they’ll find out.”

All too often, the phrase “He did exactly what he wanted to in life” is a euphemism for “He treated the people around him like toilet paper.” But George Wein did exactly what he wanted to, and in eight years of research and writing — in probably 100 interviews with famous people and hardworking behind-the-scenesters — I never heard one person say “George Wein? Screw that guy — lemme tell you what he’s REALLY like.” Not one.

You don’t have to like jazz or folk music to think that’s a life to be emulated.