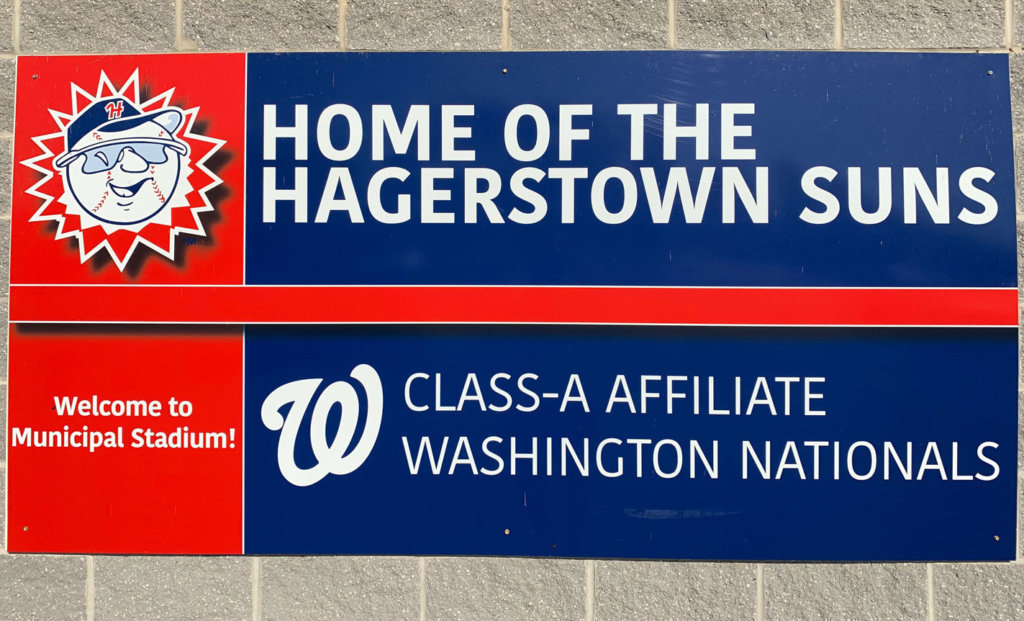

The automated voice that greets you when you call the Hagerstown Suns’ front office announces the club as “your single-A affiliate of the World Champion Washington Nationals.” This should be a time of celebration, considering 17 former Suns players and coaches were part of the Nats’ incredible run, including stars such as Juan Soto, who played in Hagerstown as recently as 2018.

But for dozens of minor league teams this winter — including both the Suns and the Frederick Keys, a Baltimore Orioles affiliate — the hope and anticipation of the season to come has been replaced by anger and fear. That’s because, if Major League Baseball has its way, next spring may be their last.

Baseball America first broke the news in mid-October that MLB was planning to slash 42 minor league clubs — more than a quarter of the total amount — at the conclusion of the current Professional Baseball Agreement at the end of the 2020 season. The proposal would also move certain clubs up or down levels to help balance out the remaining leagues and cut down on travel, focus on upgrading infrastructure, and at least somewhat improve upon the substandard minor league player pay, which MLB has largely done everything in its power not to fix over the last few years.

There are arguments to be made that some of the low-level leagues that simply function out of Spring Training complexes and don’t draw many fans outside of February and March are superfluous. But a number of the proposed teams on MLB’s chopping block are long-held community institutions with rich histories in which municipalities for decades have invested energy and public money.

***

Todd Bolton is a retired National Park Ranger born in Alexandria, Virginia, who moved to Washington County 42 years ago. He’d never been to a minor league game before he attended his first Suns game.

“We didn’t have a lot of money when we were young and the kids were growing up,” he said. “So the opportunity to bring our family out here — my wife and two small children out here to enjoy baseball at an affordable price — where we could, at best, take the kids down to Memorial Stadium (in Baltimore) once or twice a season because it was so expensive. But we were out here all the time. It was great, it was exciting, it was up close.”

Unlike Major League teams, which can lean on record television revenues and ever-increasing ticket, concessions, parking and merchandise prices for gaudy profits, minor league clubs mostly operate on thin margins. They also provide something their big league brethren don’t — affordable entertainment for middle- and working-class families.

“In terms of the current economy, it’s just as much of a value today for a family as it was for me and my family back in the early 80s,” said Bolton. “It’s a bargain.”

Bolton was also an old Senators fan, and his newfound connection to the Nationals (the Suns have been affiliates since 2007) reignited his Washington fandom. He now makes the trek to South Capitol Street 10 times a year to see the Nats.

“I would think the Nationals would absolutely want to bend over backward to keep a presence in the state of Maryland,” he said. “Every other affiliate in this state is a Baltimore Orioles affiliate.”

The Nationals declined to comment on the MLB proposal.

***

Just down Interstate 70 in Frederick, Maryland, the Keys are facing the same fate. An Orioles affiliate since 1982, they were equally gobsmacked by the news.

“We weren’t aware of what was happening; we weren’t aware of the 42 teams, and certainly we weren’t aware of Frederick,” Keys owner Ken Young, who also owns the Bowie Baysox and Norfolk Tides, told WTOP. “So it was a complete surprise to us.”

Harry Grove Stadium, which the Keys have called home since 1990, isn’t exactly new, but it’s hardly falling apart, either. And whatever improvements the facility might benefit from, their absence hasn’t chased fans away. The Keys are consistently one of the top draws in the Carolina League and led the circuit in attendance this year.

“There’s no rhyme or reason that Frederick should be on that list,” said Young. “Just none at all.”

Young said he’s met with the Orioles, who he says seemed to have been caught off guard by MLB’s plans, even though owners approved the proposal 30-0. Young will have further meetings in San Diego, where he’ll hope to impart what he considers the most vital message in all of this.

“It’s how important these teams are in these smaller communities to the overall health of Major League Baseball,” he said. “That’s where fans are developed, that’s where traditions start, and that’s a message that somehow maybe with this new administration of Major League Baseball, has gotten lost.”

MLB has done plenty of hand-wringing over the last few years about stagnating growth among young people and how to create lifelong fans of the game. But minor league ball offers one of the most accessible price points to get more kids in the stands, something Suns season-ticket holder and president of Visit Hagerstown Dan Spedden can attest to firsthand.

He and his wife brought their son to his first Suns game when he was 8-days-old. As he grew up, he became a bat boy, helped track pitches from behind the backstop and worked in the clubhouse, the dugout and the press box. Now in his 20s, he’s the managing editor for Ballpark Digest.

***

Minor League Baseball has known about the proposal for months before it leaked, working behind the scenes to mitigate damage to its member clubs and find a better solution than cutting entire franchises wholesale.

“Obviously, this was a little more drastic than anybody wanted to see,” MiLB Senior Director of Communications Jeff Lantz told WTOP.

Since the news broke, each side has fought to sway public opinion through public letters. MLB claims to spend $500 million annually on minor league players, to get just $18 million in return.

Baseball America’s JJ Cooper pointed out that a vast majority of MLB’s figure comes from draft bonuses ($316.5 million in 2019) and international signing bonuses (more than $100 million), not actual salaries. The proposal includes cutting the bottom 20 rounds of the draft, and the minor league salaries that come with them. That will certainly reduce some overall cost, but most of that $500 million is going to be spent anyway.

As Cooper pointed out, the signing bonus for a player at the top of the first round is going to cost more than those for every player from rounds 21-40 combined.

Meanwhile, the $18 million MiLB sends MLB in ticket taxes doesn’t take into account the full amount they spend on helping take care of and develop their parent club’s players. MiLB conservatively estimated that expense is more than triple the ticket tax, in the range of $60 million annually.

The two sides met at the MLB Owners Meetings in Arlington in late November, an encounter Lantz described as “cordial and productive,” despite the rhetoric flying around. And while the sides are set to meet again at the Baseball Winter Meetings in San Diego starting this weekend, it’s unlikely we’ll see any kind of concrete resolution out of that affair either.

In the meantime, MiLB President Pat O’Conner met with lawmakers Tuesday on Capitol Hill as they announced the formation of the Save Minor League Baseball Task Force. While he was encouraged by the support Congress has shown — gathering on the way into the Thanksgiving Holiday, despite other pressing business, to collect 106 signatures of bipartisan support on a letter to MLB — he was blunt about the state of affairs.

“This is an existential threat to our organization,” he told WTOP. “If this happens in this way, at this time, what’s to stop it from happening in the future? Too many good communities have invested good time and good money to always be looking over their shoulder.”

***

There is, for starters, the sunk municipal cost of the stadiums that have already been built and/or renovated in recent years by minor league cities. And there are the major expenditures of the past still being amortized, like New York City dropping $71 million for a stadium for the Staten Island Yankees in 2001.

Rep. Max Rose, D-NY, represents Staten Island. He didn’t mince words at the event on Capitol Hill Tuesday.

“Profit ain’t everything. We’re talking about community. We’re talking about the very backbone of our neighborhoods,” he said. “Just so a couple of billionaires can, what, buy another yacht? We’re going to turn our backs on these communities? It’s disgusting.”

There are far more recent examples of municipalities devoting public money to MiLB infrastructure, such as the $12 million Pennsylvania gave the Erie SeaWolves and the $5.1 million in city and state money the Binghamton Rumble Ponies received for renovations — both just last year. Add it all up in every minor league baseball community around the country, and the total invested is in the hundreds of millions.

“Look at how much those communities have invested in these teams. There’s a greater responsibility here,” said Spedden. “It’s obnoxious behavior on the part of Major League Baseball. There’s way too much on the line for small towns like ours.”

And then there’s Hagerstown. Not every team barking for a new ballpark needs one — the Atlanta Braves and Texas Rangers both recently replaced their former homes, each built in the mid-90s — but the Suns are overdue.

Municipal Stadium turned 90 years old this year. Willie Mays played his first professional game there in 1950; four decades later, George H.W. Bush visited Municipal Stadium and became the first sitting president to attend a minor league game.

Built in just six weeks in 1930, it lacks nearly every modern ballpark amenity. Minor improvements have been made over the years, but the original grandstand remains in place, along with the uneven grade of the outfield grass, the result of being constructed atop a hard, rocky surface. They couldn’t even host World Series watch parties this fall, because the water gets turned off once the minor league season ends.

Rep. David Trone, D-Md., has attended minor league games his whole life, from Wilmington, Delaware, to Greenville, South Carolina. He’s been working with the Suns for more than a year on a potential new facility.

“All these little minor league teams are part and parcel of the fabric of small-town America,” Trone told WTOP.

MLB saw record profits of $10.3 billion in 2018. Considering the massive taxpayer benefits Major League Baseball teams have enjoyed, including more than $700 million for Nationals Park, Trone — whose district is home to both the Suns and the Keys — balks at the league’s treatment of the minors.

“Major League Baseball has set a world record for taking money from the public coffers,” he said. “How much money is enough for MLB teams, and don’t they have an obligation to support the minor leagues?”

***

Hagerstown may not have money invested in a new ballpark yet, but just removing the Suns would crush the local economy. Suns GM Travis Painter has done an economic analysis of the money the club brings in, from concessions contracts, hotel rooms for visiting players, families and Nationals officials, and of course taxes on all of the above. Even in their old digs, that number is $4-$5 million per year, a figure one would only expect to rise in a new venue (especially one equipped to host other events). And that analysis doesn’t account for the economic stimulus of increased pay for the minor leaguers who call Hagerstown home five months a year.

“Figuring in all those factors, then you just kind of take it away, that’s going to leave a big blight within the community,” said Painter.

Unlike large cities, entertainment options are more limited in places like Hagerstown, where the moniker of “minor league” may not fully reflect just how big a role an organization plays in civic life.

“The Hagerstown Suns are the city of Hagerstown’s No. 1 tourist attraction,” said Spedden. “It’s one of the things that we dangle in front of everyone who’s coming to town, whether it’s a heritage or cultural tour, whether you’re here for your kid’s sports tournament, whether it’s just a convenient stop on I-81 heading north or south.”

There are clinics held by the pro ballplayers, inspiring and instructing the next generation. But there are also the ways teams impact their communities that the average person might not see, like the newly painted kitchens at The Women’s Club or the landscaping outside the YMCA, both courtesy of the Suns front office staff. In all, from the donated tickets and services, it comes out to about $40,000 a year in Hagerstown, and in towns across the country with minor league clubs, all of which might evaporate.

“I’m really sad, because it’s such a wonderful thing for this community,” said Bolton. “I don’t think people realize what a blessing it is.”

***

Another component of MLB’s plan is converting existing teams into independent clubs as part of a “Dream League.” But Cooper surmises the franchise values of suddenly nonaffiliated teams would instantly plummet. There would no longer be the opportunity to see Major League stars of the future up close, something important to hardcore baseball fans. Big-league players wouldn’t be swinging through town on injury rehab stints. And there’s the inherent stability a Professional Development Contract provides, knowing that a big-league club is invested in your success.

Put another way, if independent league baseball was a wildly profitable venture, there would be successful independent leagues all over the country. Arguably the top indy league in the country is the eight-member Atlantic League (MLB’s new rules testing ground), formed in 1998. Only two of the league’s founding members remain, and one is a permanently traveling road team with no home ballpark. In addition to the six original teams that have folded, two others — the Aberdeen Arsenal (2000) and Camden Riversharks (2001-15) — have come and gone in the interim.

Meanwhile, the Chattanooga Lookouts, another of the MiLB teams on the chopping block, have been around since 1885, 69 years before the St. Louis Browns moved to Baltimore to become the Orioles, and 120 years before the Montreal Expos moved to Washington to become the Nationals.

There’s good reason for that. As Bill Madden pointed out in the New York Daily News, the added cost on top of operational costs that minor league teams already pay of player, coach and trainer salaries, equipment, and insurance costs currently born by the big league parent clubs would cost something between $350,000-$450,000 a year. That’s not even the Major League minimum salary for the last guy on a big league roster ($555,000 in 2019), but it’s more than entire annual front office payrolls for some lower-level minor league clubs.

“We’re more than willing to participate in the development, but it’s got to be fair and equitable,” said O’Conner.

***

Back in Hagerstown, they wait. The news of MLB’s plans has already put teams such as the Suns at a significant disadvantage in trying to motivate sponsors for the upcoming season, not to mention their broader effort to move ahead on a new ballpark.

The league issued a statement on Monday, following a meeting between Commissioner Rob Manfred and Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., that included the following sentence:

“MLB is committed to negotiating with Minor League Baseball to find solutions that balance the competing interests of local communities, MLB Clubs, Minor League owners, and the young players who pursue their dream of becoming professional baseball players.”

But Spedden doesn’t believe those interests are in competition with each other at all.

“You can imagine how disruptive this news from Major League Baseball has been to what we’re trying to accomplish here,” he said. “What they want is better facilities. And what they’re making it harder for me to provide is better facilities.”

There is anxiety, but there is also palpable anger about how cavalierly they’re being treated by Major League ownership.

“You’re a temporary fixture on the landscape. You should be more of a steward of the game than this,” said Spedden. “Was that your legacy? To have ruined it? I think they’ve got to think long and hard about what they really own. It’s not just their team. It’s part of the heart of America.”

Spedden’s already-uphill battle to convince his town to invest in its team has been compounded by the management consulting attitude that’s leaked into MLB offices everywhere, in which this proposal is steeped. Spedden’s talking about Hagerstown, but he might as well be talking about baseball itself, and its myopic push to shave every bit of perceived excess at the edges without any long term consideration of what far-reaching effects such an approach might bring about.

“It’s as if they think you could cut your way into prosperity,” he said. “Well, you can’t. Every time you cut, you get less back.”