This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan Jr. (R) unveiled a $58.2 billion spending plan last month that increased state education funding, but advocates and lawmakers claim that he excluded funds slated to go to some of the state’s most underfunded school systems.

According to a fiscal briefing by the Department of Legislative Services, Hogan’s fiscal 2023 budget does not include $140 million for specific programs stipulated in the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future, a multibillion-dollar education reform plan that ramps up this budget year. Around $125.5 million of the funding at issue is specifically intended for the Baltimore City and Prince George’s County school systems.

At issue is a funding provision in the Blueprint called the “education effort adjustment,” which offset costs for jurisdictions unable to raise enough taxes to fund their local shares of education reform costs. The adjustment allows the state to step in when money runs out at the local level, after recognizing the funding efforts made by local governments.

For fiscal year 2023, legislative analysts say that adjustment should be $99 million for the city of Baltimore and $26.5 million for Prince George’s County. Legislators representing Baltimore and Prince George’s are demanding that Hogan issue a supplementary budget that includes this adjustment funding.

But Hogan spokesman Michael Ricci said that budget mandates typically have “well-defined data points,” and the Department of Budget and Management was not provided with the necessary data to calculate the education effort adjustment for the upcoming fiscal year. He called the funding that lawmakers are calling for a projection, rather than a mandate as defined by state law. “A projection is not a mandate,” Ricci said.

According to the Department of Legislative Services, an attorney general opinion issued in 1980 concluded that budget language passed by the General Assembly must “clearly prescribe a dollar amount or an objective basis from which a level of funding can easily be computed.”

Ricci said when state budget officials asked the Department of Legislative Services how they calculated the education effort adjustment, they did not receive a response. “This lends credence to the notion that DLS used a projection rather than hard data, since some data points do not exist,” Ricci said.

Ricci said he expects that all of the data needed to calculate the education effort adjustment will exist in fiscal year 2024.

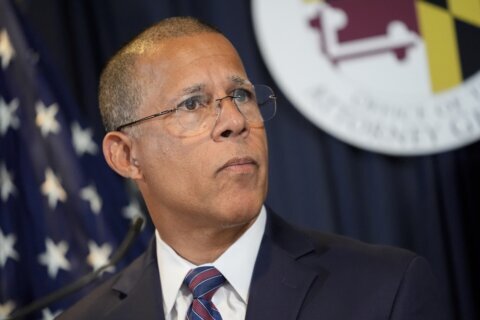

In a letter to the governor, Senate President Bill Ferguson (D-Baltimore) and House Speaker Adrienne Jones (D-Baltimore County) this week, Isiah Leggett, the chair of the Blueprint’s Accountability and Implementation Board, wrote that the Office of the Attorney General has been asked to weigh in on whether the funds are mandated for the fiscal year 2023 budget currently under debate.

Del. Stephanie Smith (D-Baltimore), chair of the Baltimore City House delegation, said that the funding is necessary to comply with the Maryland constitution, which states all students must be provided with a free and adequate public education. Baltimore City Public Schools has more students in poverty, more students who are learning English, and more special education students, she continued.

In Baltimore City Public Schools, 77% of students are Black and 92% are students of color, according to Christopher Meyer, a research analyst for the Maryland Center on Economic Policy. “This really is a targeted cut,” he said. Fifty-four percent of students are Black and 96% are students of color in Prince George’s County public schools, he continued.

“I’m incredibly energized to demand that the governor of this great state move the money in a supplemental budget to where it rightfully belongs — with Baltimore City public school students and their families,” Smith said in a press conference hosted by Strong Schools Maryland, a grassroots organization advocating for the Blueprint, on Thursday.

Del. Nick Charles (D-Prince George’s), the chair of the Prince George’s County House delegation, joined Smith and advocates in pressing for the funding this coming year.

“We all know that education is the greatest equalizer to overcome systemic racism,” Charles said. “Governor Hogan, we are asking you to work with us and fund our damn schools — give us our money,” he said, citing the state’s historic $4.6 billion surplus.

Shamoyia Gardiner, executive director of Strong Schools Maryland, said that the intent of the Blueprint has always been to update the state education funding formulas to provide equity to all school systems across the state. She worried that not funding the counties with the most need now would set a dangerous precedent.

“The entire point of the Blueprint is to address the underfunding of our schools. And once we’ve addressed that, implement the policies that are necessary to create a world class system of public schools. It does not compute to assume otherwise,” Gardiner said.

Legislative analysts have also listed $14 million in other unfunded Blueprint programs not included in Hogan’s budget — including for staff training and curriculum development.

The Accountability and Implementation Board is also facing delays without full staff and funding and recently proposed a new timeline that pushes the implementation of the Blueprint reforms back by almost a year. The panel has also expressed concerns that revenue from the State Lottery and Gaming Control Commission meant to fund the AIB this year will come too late in the fiscal year to spend.

“Based on the flow of fantasy sports and sports betting revenues, the bulk of that funding will be received near the end of the fiscal year. The AIB will not be able to encumber it all and potentially a significant portion will revert at the end of the fiscal year,” Leggett wrote.