Aquaculture is a growing industry in Maryland. Boosting the state’s oyster population can benefit watermen, who have more oysters to harvest, and the water quality of the Chesapeake Bay.

But it’s not easy. It’s actually quite muddy, and cleaning off that mud requires manual labor. It’s also not that efficient. Typically, an oyster half shell has about 10 oyster spat implanted on it and tossed in the water. About 3% of those seeds ever grow big enough to be harvested and eaten.

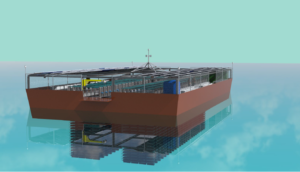

A Baltimore-based company is trying to change that. Solar Oysters LLC is building barges powered by solar energy that take up significantly less space in the water than typical aquaculture facilities, which can spread acres wide on the bottom of rivers and the Chesapeake Bay.

“A normal oyster farm is about 300,000 oysters per acre,” said Mark Rice, a manager at Solar Oysters LLC, which has been testing production on smaller barges in the waters near Solomons Island.

By 2022, the hope is that “we are producing 2.4 million oyster in a spot of water that’s 90 by 53 feet,” Rice said.

(For reference, an acre is about 75% the size of a football field, while Rice’s proposal is about 30% of a football field.)

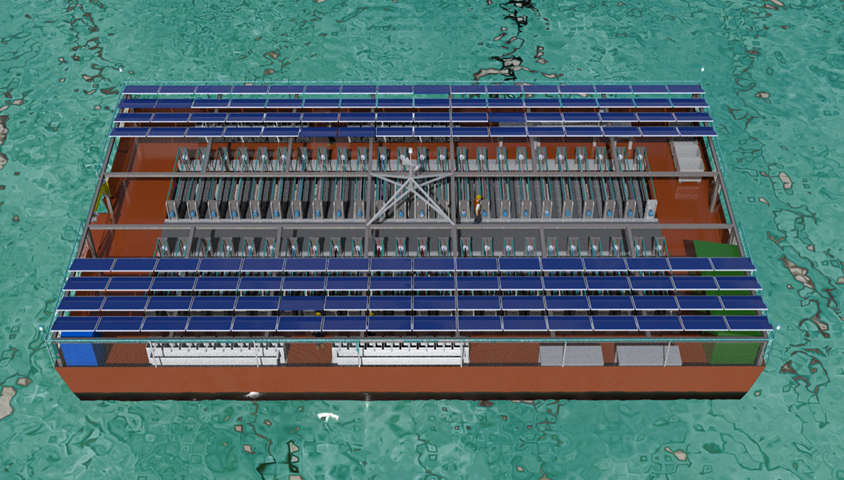

Instead of using cages at the bottom of the water, which eventually fill with mud and where oyster-killing diseases live and spread, the barges they’re building work vertically.

“We have these vertical ladders covered with cages, and those cages rotate vertically,” Rice said.

The machines rotating the cages are powered by solar panels placed on each barge. In all, it juts about 10 feet out of the water. Every other day, those oyster-filled cages are power-washed clean.

“By hanging oysters in the water column, we expose them to clean water, more oxygen, better salinity and more food sources,” Rice said.

The design also allows for air to be pumped down the ladders and into the water where the cages are, providing oxygen even when summertime dead zones start to flourish.

Each barge grows the oysters from the 10 spat on a shell until each oyster is about half an inch wide. In Maryland, oysters need to be at least 3 inches wide to be harvested and sold, so by growing them longer, it increases the likelihood that the oysters would survive long enough to mature to that size.

“Those half-inch sized oysters would go back into natural reefs to increase the population of oysters in Chesapeake Bay,” Rice said. That starts a positive chain reaction of events, since those oysters can start removing more nutrients and sediment out of the water there, which improves water quality and clarity to the benefit of underwater grasses, and thus provides more habitats for crabs, fish and other organisms that make the bay healthy.

Rice readily admits that his company is still new to the aquaculture business, and that it doesn’t have all the answers.

“We’re learning as we go; we’re learning from watermen, we’re learning from aquaculture folks,” as well as the Coast Guard and scientists working for the state and the University of Maryland.

Some of their predictions about how this new process would work proved out right, but others haven’t, he added. “We learned a lot, some good, some bad” in the prototype phase, Rice said.

In the coming months, the company is expecting to build barges with 20-by-20-foot platforms (which grows about 300,000 oysters) as they work to that 90-by-53-foot goal.

“There were once billions of oysters in Chesapeake Bay. We’re down to millions now,” Rice said.

His company wants to help put the population back in the billions. Though they’re still testing out the theory behind all this, they also need to overcome the cost. Each 90-by-53-foot barge costs almost $1 million to build.

“It’s a matter of finding the economic lever to make this happen,” Rice said. “If you’re still doing it for restoration, it still costs a lot of money to do that restoration, and with low survival rates, you don’t get there very quickly.”

But when building enough barges to boost the population for commercial watermen, the financial benefits start to expand. If each big barge is producing 2.4 million oysters per year, and 100 of those barges are put up and down the bay, there could be a billion oysters in a few years time.

“And, if you can sell those oysters at 55 cents apiece, you’re going to have a pretty good return on your investment,” Rice said.