This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

Comptroller Peter Franchot, on a continuous loop of shameless self-promotion for governor, might suffer from the Louis L. Goldstein syndrome.

Or curse.

Goldstein, for the new arrivals, was Maryland’s beloved comptroller (Louis pronounced it COMP-troller), fussbudget, cornpone, dumb-as-a-fox, country lawyer for 40 years – that’s 10 terms – and before that a legislator for 20 years, including president of the Senate. (He named one of his daughters Senate.)

In all of those decades of elective office, Goldstein got talked into one major political blunder that haunted him until the day he died in 1998 of a heart attack just after his daily morning laps in his heated swimming pool in Prince Frederick, in Calvert County.

The question for Franchot is: Will he be tempted to make the Goldstein mistake?

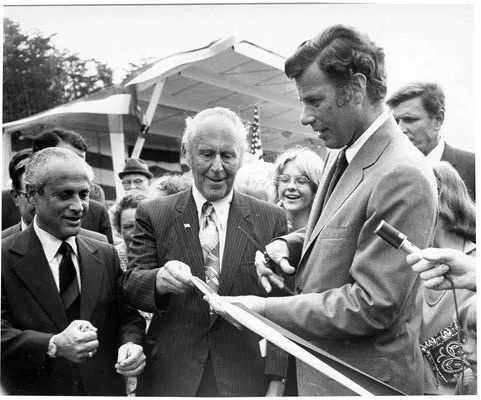

Goldstein’s was a familiar face in and away from his Annapolis office, the only comptroller Marylanders of a certain age ever knew. He was first elected in 1958 and one of only three comptrollers between then and now. Along the same timeline there have been nine full-term governors. At the time of his death, Goldstein had been the longest serving state comptroller in the history of the country. He had attended more national political conventions than any other living Democrat.

(Governors are term-limited; comptrollers are not. At Goldstein’s death in July 1998, his deputy and longtime aide, Robert L. Swann, served the remaining six months of Goldstein’s term. And in 1977, Lt. Gov. Blair Lee III assumed the governorship upon Gov. Marvin Mandel’s conviction on charges of corruption.)

Goldstein, the man, and the office of comptroller, were indistinguishable and inseparable, so much so in the voters’ minds that it was difficult to say whether the man created the office or the office created the man.

His poll numbers in the relatively new science at the time were stratospheric, his recognition was universal and his vote-pulling power was unquestioned. His bully pulpit was his seat on the three-member Board of Public Works, where he railed against government waste and regularly berated unprepared bureaucrats. As comptroller, he also headed the Board of Revenue Estimates which twice a year delivers revenue projections that help shape state budgets and determine spending.

Goldstein’s calling card was a gold souvenir medallion embossed on one side with “Louis L. Goldstein, State Comptroller, Maryland,” and on the other, his familiar benediction, “God bless y’all real good.” His other familiar catchphrase was his constant reference to his “good wife Hazel,” pronounced rapidly, “goodwifeHazel,” as if it were a single word. Hazel was also his law partner.

And as for his personal portfolio, it was said that Goldstein owned land in every county in Maryland. (He owned and sold the land to BGE for the Calvert Cliffs nuclear power plant.)

In the 1960s, Goldstein denounced computers as “idiots.” In the 1970s, The Wall Street Journal praised Goldstein’s office for having the most efficient computerized system of any comptroller’s office in the nation.

On the campaign trail, the ebullient Goldstein served as the warm-up before Sinatra. He once got so carried away in Garrett County that he ended up campaigning in West Virginia without realizing it. On another occasion, he put on a Goldstein performance in a general store in Oakland.

“My God, I’ve never seen bananas like this,” Goldstein said. “These are the most beautiful bananas I’ve ever seen. I’ve got to have some.”

To the delight of the storekeeper and the amusement of bedazzled shoppers around him, Goldstein bought a full hand of bananas – maybe a dozen – and left the store still praising the quality of his purchase. Halfway up the street and out of the store’s line of sight, Goldstein tossed the bananas into a municipal trash can.

Goldstein without question was the most popular politician in Maryland. Then something happened.

In 1964, Joseph D. Tydings, the U.S. attorney for Maryland and a friend of the Kennedys, decided to run for the U.S. Senate. The Democratic establishment – the political machine of Gov. J. Millard Tawes and his moneyman George H. Hocker – needed a candidate to block Tydings from the Democratic nomination. Besides, there was a score to settle. Tydings had indicted House Speaker A. Gordon Boone, of Baltimore County, an organization stalwart, in Maryland’s first savings and loan scandal.

Hocker settled on Goldstein. Goldstein, against his better judgment, and maybe letting his ego get the best of him, allowed himself to be talked into seeking the Senate nomination – with the promise of all the money that was needed to defeat Tydings in the primary election. After all, Goldstein had never lost an election, even the one while he took a leave of absence from the legislature to fight as a Marine in World War II.

But times they were a-changing. The civil rights movement and the anti-Vietnam War sentiment were just beginning to coalesce into an epic anti-incumbent public rage among a new generation of reform-minded voters, dubbed “shiny brights” in the local press. And Goldstein seemed out of his element when juxtaposed with Tydings, the young Kennedy chum and cool gangbuster.

But there was another pathology in play, too. Goldstein was so identified with the state office of comptroller and the cornpone persona that he had created for himself that the voters were reluctant to award him a resume upgrade to the U.S. Senate where the air is more rarefied, or so they like to think.

They loved Goldstein and wanted him to remain where he was. Goldstein got hammered in the only election he ever lost. He happily retreated to being reelected comptroller time and again for another 34 years.

And so it goes with Franchot. He’s now in his fourth term as comptroller, well on his way to the Goldstein trap of being indistinguishable from the job and stuck with it for better or worse. The last comptroller to be elected governor was Tawes in 1958, and that was after two attempts.

In his own way, Franchot is a giant killer. After all, he vanquished the persnickety and increasingly loopy William Donald Schaefer from a lifetime of public service as mayor of Baltimore, governor and, lastly, comptroller, after he was elected to succeed Goldstein. (Schaefer’s downfall came when he asked a governor’s young female aide at a Board of Public Works meeting to turn around and walk by again so he could get a second, better view of her backside. The public outcry was measurable in high-pitched decibels, especially from the young woman’s father.)

To roughly paraphrase Shakespeare, comparisons suck. But it’s easy to see that Franchot mimics the comptroller model perfected by Goldstein right down to handing out rip-off medallions, spending more time out of the office than in, where machines do most of the work. (Goldstein routinely arrived at his office at 7:30 a.m., well ahead of the office staff, personally answered the phones for an hour and then vanished to some ceremonial or campaign functions out in the boondocks. Voters marveled that Goldstein answered his own phone.)

Franchot has few friends in officialdom, but he has a boatload of enemies who would welcome a chance to trounce him at the polls. And after all, members of the General Assembly are an important part of the Democrats’ voter delivery system.

But Franchot can counter that in the last election he received the most votes of any candidate in Maryland history – and it’s smart to remember they were for comptroller. And in his turn, Franchot rails against the Annapolis Democratic machine.

Franchot has cultivated constituencies that rely on the comptroller’s office such as craft brewers and the seasonal merchants at Ocean City. In doing so, he has angered members of the General Assembly who have chipped away at his regulatory authority and the responsibilities of his office

He has formed an alliance with the Republican governor, Larry Hogan, which is a further irritant to Assembly Democrats. The resentment of his showboating is a hangover from Franchot’s years in the House of Delegates, too much of an outlier to be governor.

And now Franchot, 71, in a fundraising letter, has said that he is “seriously considering” running for governor, the customary cheap feeler tossed out to reel in reactions as well as money. Once before, near the conclusion of his second term as comptroller, Franchot employed the same self-serving device and decided to stay put, in his comfort zone, relieved after the decision, safe in the comptroller’s office building that is named for Goldstein.