This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

If Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan Jr.’s call for new mandatory minimum sentences for repeat violent offenders fails to generate fresh traction in Annapolis, it will primarily be because many lawmakers trust judges more than prosecutors — or politicians.

Late last week, in the wake of another wave of highly-publicized crimes — including the shooting of a police sergeant in Baltimore City — Hogan (R) took to social media to condemn the violence and urge action.

“This senseless violence must stop,” he said on Twitter.

“We’re talking about taking our communities back and saving lives—the time has come for us to take a stand together. I am calling on city and legislative leaders to support our legislation to impose tougher mandatory sentences for those who repeatedly commit violent crimes with guns,” he wrote.

Hogan’s press office followed up on Saturday with details of what he wants: a minimum sentence of five years in prison for a person who commits a first violent crime with a firearm, with 10 years behind bars for a second or subsequent offense.

The proposal mirrored a bill Hogan proposed in January, The Repeat Firearms Offender Act of 2019. The measure had a hearing in each chamber, but lawmakers never voted on it.

Hogan’s new push is not likely to fare much better.

“The science and the research is really inconclusive about whether [mandatory minimum sentences] deter crime — and that’s what we all want,” said Del. Shelly L. Hettleman (D-Baltimore County).

Like many of the current and former officials interviewed over the weekend, Hettleman said mandatory minimums weaken the ability of judges to weigh each case on its merits.

“By taking discretion out of the hands of judges, they hope to eliminate disparities in sentencing,” she said. “But what they really do is shift discretion from the judges to prosecutors.”

In Baltimore and elsewhere, prosecutors have wide discretion in which charges they file. And lawmakers from both parties said they are often influenced by the presence of mandatory minimum sentence laws.

Del. Nick J. Mosby (D-Baltimore City), who opposes mandatory minimums, said high-crime communities need greater investment in education, job opportunities and police reform — “not this ‘tough-on-crime’ approach.”

“If we’re serious about driving down crime, particularly in places like Baltimore City, we’ll be serious about breaking up concentrated pockets of poverty,” he said.

Mosby noted that the legislature passed a bill, with bipartisan support, in 2018 to require new mandatory minimum sentences for certain offenses, yet Baltimore City continues to see massive bloodshed.

They “clearly have not worked,” he said of the new sanctions. “They frankly have failed miserably.”

According to the legislative analysis of Hogan’s 2019 bill, new inmates cost the state $895 per month, excluding overhead ($3,800 per month including overhead).

Sen. Michael J. Hough (R-Frederick & Carroll), a member of the Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee, said mandatory minimum sentences tend to work in places where prosecutors adopt a tougher stance on crime, but not in places like Baltimore City.

“We pass them, but they don’t use them,” he said, a reference to the city’s locally-elected prosecutors.

Hough said he intends to introduce a measure in 2020 to close a “hole” in existing law on gun crimes.

“I don’t want to go back to mandatory minimums for drug trafficking,” he said, echoing a view held by many Democratic lawmakers. “I think that was not a good policy.”

“But if somebody is using a firearm in commission of a violent act, those are the kinds of people that deserve prison time,” Hough added.

Polling over the last decade has shown a sharp decrease in support for mandatory minimum sentences for drug crimes. Research on their use in crimes of violence has drawn mixed conclusions.

According to the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine, “Community-based programs and focused policing interventions in general have been found to be effective in reducing violence in some settings (e.g., high-risk physical locations) and appear to be more effective than prosecutorial policies, including mandatory sentences” their report concludes.

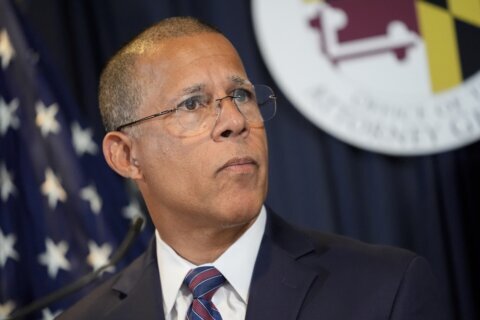

Former state attorney general Douglas F. Gansler (D), who served as a federal prosecutor before entering politics, said there is “one mandatory minimum that we ought to have. A convicted felon who uses a gun in the commission of a subsequent offense should be given a five-year mandatory minimum,” the standard in the federal system.

“If you’re against that proposition, then you have no right to complain about violent crime or murder in Baltimore,” he added, “because that is precisely the person who needs to be removed from the streets.”

But Gansler, who served two terms as Montgomery County state’s attorney and two terms as state AG before running for governor in 2014, sees the flip side of the argument as well.

“The biggest problem with mandatory minimums in general is that you’re taking the discretion away from the judge to appropriately match the criminal and his or her history with the crime that he or she just committed.”

“Every criminal is different and every crime is different,” Gansler said, “so there’s a premium that’s placed on judicial discretion — and rightfully so.”