Deep inside Walter Reed’s massive Bethesda, Maryland, campus, injured U.S. service members are hiking in the hills and dodging sharks on unsteady seas — all thanks to technology designed specifically to help rehabilitate them.

The system is called CAREN — Computer Assisted Rehab Environment. It’s one of only 10 of its kind and is used to help wounded veterans deal with challenges such as adapting to new prosthetics, coping with stress and re-learning balance and other skills.

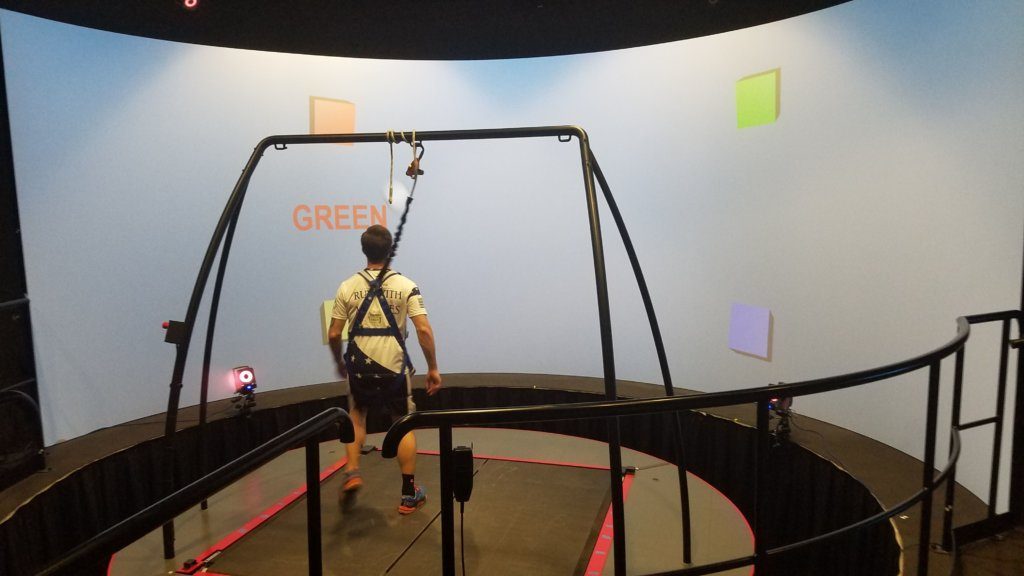

CAREN looks like a huge, personal IMAX screen that wraps around a central platform that houses two side-by-side treadmills. The platform can also be raised or lowered and can tilt along its axis to mimic rising or falling terrain.

The project has been a boon to recovering service members.

In 2016, Marine Cpt. Jason Settlecowski was diagnosed with stage 2 brain cancer. It impacted his left motor cortex (which controls voluntary movement) as well as his somatosensory cortex (which receives sensory input from the body). Both are critical for humans to move properly.

A couple years later, Settlecowski had surgery to remove “about a sugar cube worth of brain matter from my left somatosensory cortex,” he told WTOP during a therapy session at Walter Reed.

“So basically, that affected my right leg from, say — the right side of my foot was numb almost, or it had a very dull sensation, and then that traversed all the way up through the back of my leg basically all the way up through my hip.”

That made merely walking extraordinarily hard.

“The eye-foot coordination was not there at all,” Settlecowski said. “I had no idea how high to lift my leg or my foot or even how far to bend my foot or take a step forward. … It was a difficult recovery there for about a month or so, and then your brain starts rewiring itself.”

But Settlecowski cautioned: It has to be rewired in the right way. “And that’s what we’re here for.”

Settlecowski said he spent a lot of time in simulators for the V-22 Osprey, so he was able to quickly adapt to the CAREN system.

He was blown away by the technology and what physical therapists can offer: “It’s just amazing. I didn’t even know it existed or was possible.”

Motion-sensing cameras ring the walls around the central platform that Settlecowski is hooked into. The cameras, as well as sensors in side-by-side treadmills on the platform itself, track his movements and speed, as well as how his feet are landing.

Settlecowski’s session starts with a simulated hike along a wooded path through digital hills, where occasional wildlife pop up near the edges of the curved screen.

A second game is more physically and mentally demanding: Using motion-tracking sensors (little white balls) attached to his back, he has to jump to a square the color a certain text is, not the color the text spells.

A third game tasks Settlecowski with guiding a boat through a tropical bay, slaloming between buoys and dodging sharks as the central platform tilts. With a laugh, one of the doctors threatens the Marine with rougher seas.

The fourth scenario required Settlecowski to put the sensors on the back of his hands. His mission was to use the treadmills to walk through creepy woods while swatting down pesky birds and bugs with his hands.

Settlecowski and his doctors playfully ribbed each other over his scores during the session, like pals playing video games on the couch in the living room.

Walter Reed has been using technology and video games for years to help patients.

Dr. Barri Schnall, who treats Settlecowski, has been with Walter Reed for almost two decades. She called the CAREN program and the therapy “an iterative process.”

“We’re constantly adapting to meet whatever the military demands are, the mission needs are at the time,” Schnall said. “We’re always changing.”

She explained that the program is based on need.

“In the winter time, we have a big demand for adaptive sports. … We do an adaptive ski program which utilizes the virtual environment,” Schnall said. “We work on weight shifting and balance, and we actually have a ski scene that incorporates use of ski equipment.”

“Patients with amputations, for example, can come down with their prosthetist (a specialist in prosthetics) and we can set them up on the system, and simulate going down a green slope, a blue or a black.”

This allows patients to test their prostheses, and the prosthetist is there to make adjustments and optimize their components, minimizing time spent doing that on the mountain.

“We’ve gotten great feedback from a confidence standpoint,” Schnall said. She and her team regularly survey their patients.

“People who have bilateral lower extremity amputations who are using a monoski, they’re able to sit in an actual monoski bucket on the system and feel what it’s like to go down a mountain.”

Schnall says it’s a huge advantage and a confidence builder for American service members.

Different patients have different needs, and the first part of the therapy process for Settlecowski revolved around collecting data for analysis from the Biomechanics Lab (called the Gait Lab by some), next door to the CAREN.

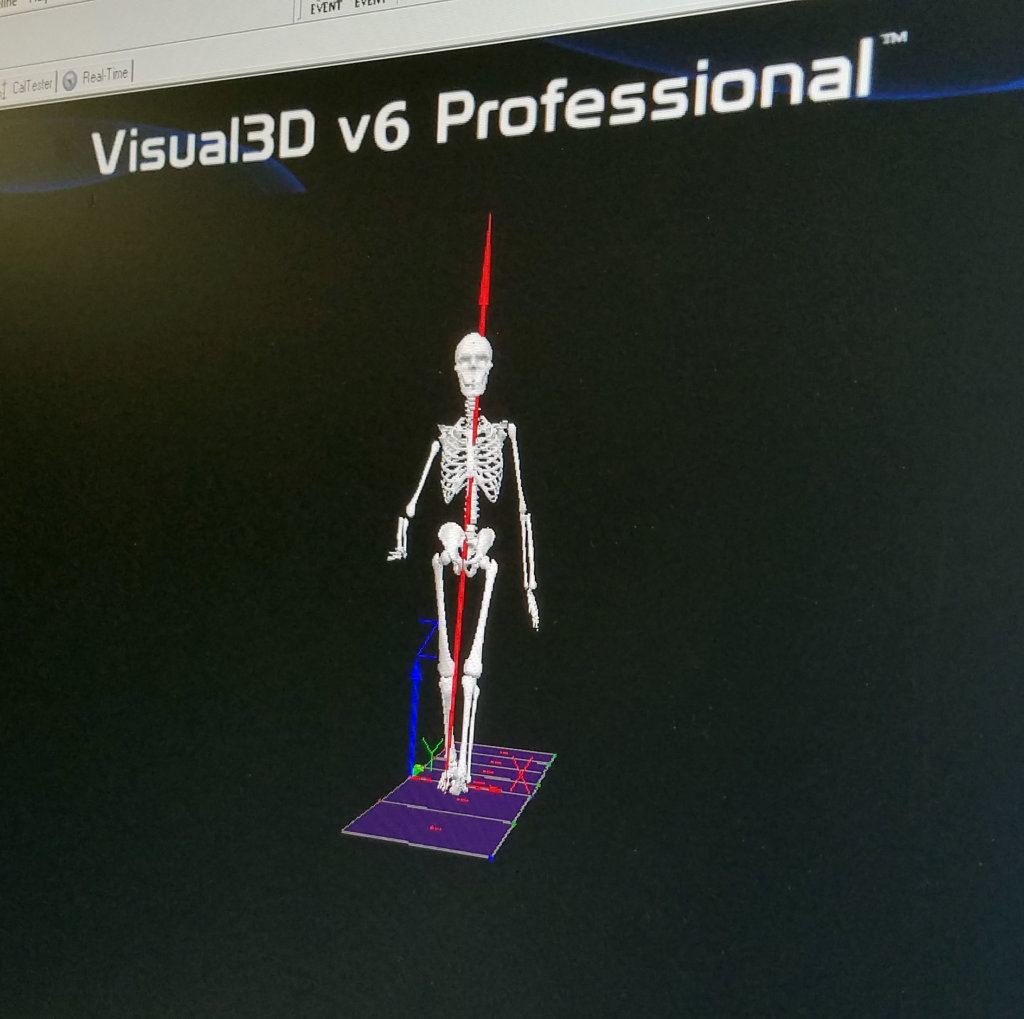

A full-body marker set is attached to patients — similar to what Hollywood uses for motion-capture in movies — who then walk across pressure plates in front of 27 infrared cameras.

“I think I said there’s a ‘Game of Thrones’ prequel I was being interviewed for or something,” Settlecowski joked.

Data collected through the analysis is then used to develop and/or modify treatment for service members.

Patients can even see how their bones are behaving when they move, thanks to 3D animations created by analytical software.

“And after all the data was processed, I got to see my muscular-skeletal system, and we were able to tell exactly where the deficits were,” Settlecowski explained. “Even before [Schnall] saw all the data, she knew that in my right foot, where I said it was numb, she saw it kind of kicking out and then coming down. And then she said, ‘Yeah, that pain’s probably translated up through your knee and your hip.’ And I didn’t even tell her that.”

“She knew just from looking at the data and the skeletal representation where the pain would be and where it would translate to and I said, ‘Yeah, dead on.'”

Settlecowski says the program is important to develop a comprehensive plan for care for service members because it gives the medical staff a way to probe the source of their pain.

“If I came in and just said, ‘My hip is hurting,’ then they might just focus on the hip area instead of where the problem is originating, which is in my foot,” he said.

A wide variety of experts are employed to get to the root of the problem.

“Everybody can contribute their perspective, culminating in the most efficient plan for the patient and [eliminating] guesswork,” Schnall said.

The program also gets digital video of the sessions, not just motion capture.

Those cameras “can give us digital video that we can then overlay with the markers, what we get with the motion capture cameras, so you can get two different pictures of it,” said Dr. Sarah Bass, who works alongside Schnall.

“We can use it as a system of checks and balances,” Schnall said. “The information that we get from the biomechanics is all the time-distance aspects of somebody’s walking. We also get all the joint angles, which we call the kinematics. And that’s without respect to any kind of forces. It’s just: Do they land with one knee straighter than the other? Do they bend their hip more on one side than the other? The most meaningful data for me is the force and power data because you cannot obtain that through observation.”

Patients are also compared to an uninjured control group with data collected from other military members in the Biomechanics Lab.

“We want to serve whatever the need of the day is,” Schnall said. “We’re trying to meet the needs of all of our service members and work with our sister sites.”

She noted that CAREN is an expensive system — not every facility will have it — and that they can’t process all the service members whom it can help at Walter Reed.

“However, if we can continue the research and get funding to support additional research to validate the CAREN as a rehab tool, and be able to say, ‘This correlates well to this type of training’ … There are readily available VR headsets that we can potentially validate using the CAREN and vice-versa,” Schnall said.

Bass explained that the CAREN system works on various levels. Less-expensive, less-complicated versions can be used clinically to treat the troops as well.

“I think if we can show that it really is good for outcome measures (assessing a patient’s status), or it correlates to some good outcome measures, then it’s a greater justification to have them more available in clinics and to help people justify people getting some version of them in their clinic,” she said.

Schnall and Bass agreed that increasing awareness of programs available for veterans at Walter Reed is a great way for the public to help and support their efforts.

For those who want to donate to support the troops, Charity Navigator (itself a charity) put together a list of 10 charities they view as the best at helping wounded service members.

They include:

- Rockville, Maryland-based Fisher House Foundation

- Silver Spring, Maryland-based Air Warrior Courage Foundation

- Bethesda, Maryland-based Operation Second Chance

- Springfield, Virginia-based Hope For The Warriors

- The Gary Sinise Foundation

- The Semper Fi Fund

- The Special Operations Warrior Foundation

- Freedom Service Dogs of America

- Operation Homefront

- The Navy-Marine Corps Relief Society