Tucked away in an upscale hotel in the 2,300-year-old Greek city of Thessaloniki, 50 Ukrainian refugees, living in 16 European countries spent four days in late February and early March immersed in an intense project designed to upend Moscow’s high-powered, sprawling disinformation operations — one voice at a time.

The hotel buzzed with activity from early morning until, oftentimes, the wee hours of the next day, during the event called “TechCamp Thessaloniki 2024: Empowering Ukrainian Voices.”

The participants, many reeling from the deep scars of war, the uncertainty of displacement, but propelled by the burning drive to fight back, listened intently as eight international journalists, storytellers, oral historians and multimedia professionals spoke to them in aptly named “breakout rooms.”

The plan was to share with them the modern tactics, techniques and tools they would need to smash through the complex layers of destructive influence campaigns run by the Kremlin.

The aim of the overall project, run by the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, was “limiting foreign malign influence and building strong people-to-people ties by promoting global alliances built upon shared democratic values.”

The instructors were brought in by program designers J.B. Aloys and Nolan Herrin to teach and mentor the participants as they developed projects to help themselves, other Ukrainian refugees, and those still at home, braving daily Russian attacks.

Aloys is a veteran of TechCamp projects in Vietnam, Kenya and New Zealand, and said the program has a unique format of gathering a lot of people together.

“In this one specifically, they came from all over Europe, all of them Ukrainian,” Aloys said. “And we have trainers from around the world and the U.S., teaching them a variety of topics and tools they can use to help promote their voices and tell their stories.”

Partnering with DCN Global, a multidisciplinary community of digital professionals based in Thessaloniki, TechCamp provided the participants with a space to learn, opportunities to vent their frustrations and a pathway to build a new future for themselves and Ukraine.

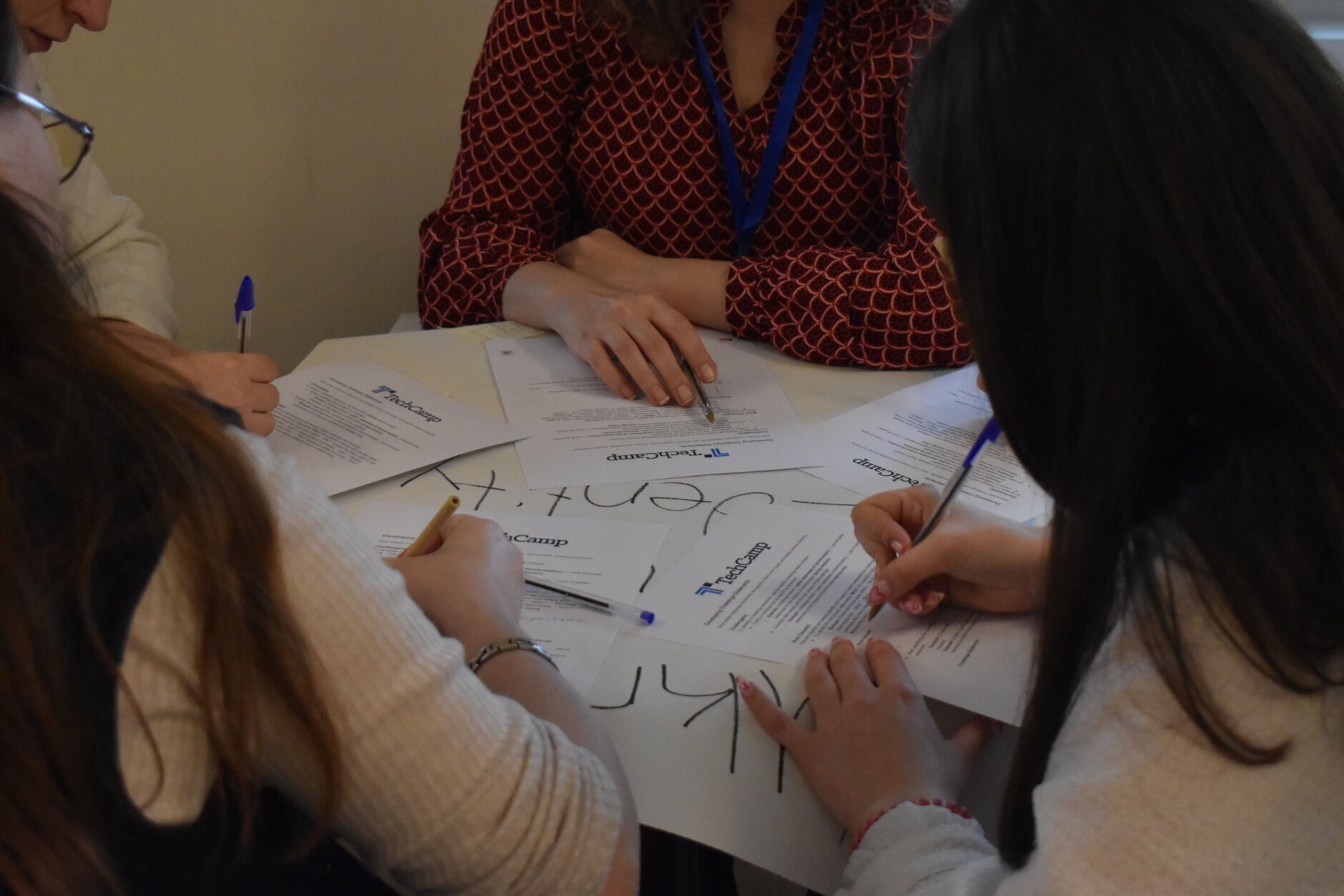

The group bonded, sharing laughter, tears and knowledge. Moreover, they strategized as they prepared to take on the Kremlin and its tools and methods of disinformation that it has used for decades before most of the participants were even born.

Initially, the participants listened to the eight coaches pitch their training sessions during a process called “Speed Geeking.” The process, similar to speed dating, allowed the participants to hear a session pitch for a few minutes before moving to another. They later decided whether they wanted to attend the sessions.

Then, they gathered to determine what their challenges would be in taking on their chosen tasks.

Next, they began attending sessions to learn more about the art of first-person storytelling, oral history collection, multimedia and mobile content creation, and reporting from war zones.

The 90-minute sessions, loaded with detailed instructions on the practical use of equipment and platforms and approaches to collect and tell stories, were also interlaced with live, virtual appearances by internationally known figures, to encourage objective thinking about sensitive issues.

The participants vigorously questioned and prodded the trainers and guests. Some sessions became uncomfortable as several participants questioned the purpose and practicality of the guests.

After the sessions the participants, clutching pens, pads and sticky notes, huddled in small teams, taking over meeting rooms, lounging spaces — even the hotel bar — to plan their operations.

The energetic participants, whose backgrounds included education, journalism, marketing, humanitarian advocacy, LGBTQ rights, science and technology and legal rights, among others, refined their own skills and learned new ones.

The challenges

Skepticism, which many participants have had to wrestle with, was one of the challenges the “Empowering Ukrainian Voices” project had to address.

Journalists are taught to employ a healthy amount of skepticism in their work. But in a culture where disinformation is rampant, it can be hard to control.

“At the beginning of 2022, journalists and everyone around warned that a war might start, but no one believed. I did not believe in it,” said Olena Cherkun, a 30-year-old journalist from Zaporizhzhia who is currently living in Spain.

“I didn’t want to believe it. But on Feb. 24, 2022, I woke up and the first thing I heard was: ‘The war has started. Ukraine is being bombed,’” said Cherkun.

That disbelief is often driven by mixed messages from influential people, said 34-year-old Maria Korolchuk, who relocated from Odesa to Romania.

“During war and uncertain times, it is vital for high-ranking officials and representatives of the state, in particular, to narrate one transparent and clear statement that cannot be misinterpreted in any way, especially during events that have high-media coverage,” Korolchuk said. “We all know that every decision, every meeting, every presence and every speech can transmit several messages.”

A key issue that presented itself at TechCamp was how meticulously many Ukrainians at the training analyzed each word used to describe the war.

To some, phrases such as “the conflict,” “the situation” or “the problem” represented deliberate attempts to minimize the Russian attacks that have killed tens of thousands of Ukrainians and displaced more than six million. Anyone using those words could expect to be corrected often and, sometimes, chastised.

During the sessions, Russians were often regarded with deep skepticism — even Russians who wanted to express solidarity with Ukrainians.

But there were practical challenges, as well.

“I think the most challenging part of TechCamp Thessaloniki 2024 was the recruitment of participants,” program designer Nolan Herrin said. He’s been with the tech camp program since May 2023.

Four hundred applicants from Ukraine living around Europe sought entry into the program, and “the hard part was selecting the right applicants who fit our profile” and would be ready for the intensive program, as well as getting them to Greece, Herrin said.

He credited DCN Global president Nikos Panagiotou and his team for identifying the participants and coordinating the logistics.

“The aim of this workshop was to create a community of action that will actually mobilize people and continue to support the struggle of Ukraine,” Panagiotou said, adding that it was important to document the participants’ stories and help them to change the narrative in Ukraine.

“We want to record their stories. We want to record the stories of war, their personal consequences. We want to empower them in various struggles against the brutal invasion,” Panagiotou said.

Depending on the West

As the participants at the training struggled with their own personal losses, disconnection from their homeland and guilt for leaving, they were profoundly disheartened by the consequences of Western hesitancy to provide Ukraine with weapons to fight off Russia’s attacks.

“I am concerned that the war is dragging on. At first, it seemed like a matter of a few months, and I would be able to return home, but now we are living in uncertainty,” said Nataliia Bozhyk, a 27-year-old journalist from Odesa.

“Every morning, I wake up with thoughts: are we living in a civilized world?” she said. “How can such a scenario be happening now? And here we are, two years later, without a single day of respite, repelling attacks and barely remembering what it was like ‘before.’”

The peace negotiations Russian and Ukrainian diplomats have begun to undertake is useless, according to Bozhyk.

“Surrendering territories and accepting Russia’s terms will not end the war. The ambitions and thirst for blood from the Russians will not disappear.”

While expressing her gratefulness to those fighting and defending Ukraine, as well as those who support her country’s fight, Bozhyk wanted to remind Western leaders that the war is not just Ukraine’s war.

“We need as much support as we can get to continue defending not only our interests but also all of Europe,” Bozhyk said.

As the intense sessions at the hotel drew to a close, each participant, either individually or in a group, had a chance to present an idea they believed would make a difference.

Some ideas will be selected to receive grants that could catapult them into viable programs. The TechCamp team believes the projects will help “foster cross-cultural understanding and amplify the voices of Ukrainian refugees by providing the necessary tools and enable them to develop their own compelling digital stories.”

Regardless of which are chosen at this time, all the participants now have an international network of friends, experts and mentors who will likely become multipliers and champions of their projects and their quests to help Ukraine win the information war with Russia — once and for all.

Get breaking news and daily headlines delivered to your email inbox by signing up here.

© 2024 WTOP. All Rights Reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.