As Pastor Harry Richard watched the flames consume Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral on Tuesday, his soul swirled with emotions.

Just two weeks earlier, on April 2, Richard’s own church, Greater Union Baptist Church in Opelousas, Louisiana, was set ablaze. It was one of three predominantly black churches in the area that were intentionally burned down, according to police.

“My heart bled for them as much as it did for my own congregation,” said Richard of the Parisians devastated by the damage to their 850-year-old cathedral.

But the Baptist pastor said he also sensed the pull of something deeper, perhaps even divine, in the aftermath of the fires.

“I think that God is using these moments to bring us closer together as a world,” Richard said. “This is God’s hand on our lives to make us realize that we are all connected in some form or fashion.”

In the days after the Notre Dame fire, as money poured in to save the iconic cathedral, an online campaign encouraged people to help rebuild the three Louisiana churches as well. By Friday, more than $2 million had been raised.

While Christians connected to the charred churches appreciate the outpouring, many say they lost more than hallowed ground and irreplaceable artifacts in the smoke and ashes. They lost a part of themselves.

“She is the soul of France,” Archbishop Michel Aupetit of Paris, whose home church is Notre Dame Cathedral, told Le Figaro this week.

And so this Sunday will, in some sense, be remembered as an Easter amid the ashes, as Christians from Louisiana to the Ile de la Cite, the island where Notre Dame Cathedral sits surrounded by the Seine River, take refuge in the hope of resurrection.

“What does the Lord want to tell us through this ordeal?” asked Aupetit. “Here we move from the scandal of death to the mystery of resurrection. Our hope will never disappoint us because it is based not on buildings of stone, which we will rebuild, but on the Risen One who remains forever.”

French connections

Like many in St. Landry Parish, Pastor Richard, whose name is pronounced “ree-SHARD,” has French ancestry.

The parish is named after St. Landry, a seventh-century Parisian bishop memorialized by St. Landry Chapel inside the Notre Dame Cathedral. Yet another connection: The first Louisiana church to burn, St. Mary Baptist Church in Port Barre, shares a patron saint with Notre Dame: Mary, the mother of Jesus.

Greater Union was built around 100 years ago, the pastor said, though it’s difficult to discern the exact date because record-keeping was erratic in those days. His grandfather, who helped construct the brick and wood church by hand, signed his name with an X, Richard said.

Richard’s grandfather is one of several family members buried on a plot of land outside Greater Union that includes his mother and father, sister and brother, grandmother and grandfather. Sometimes he takes a walk among their tombstones and talks to them.

Many of the congregation’s members also have ancestors buried in the cemetery , the pastor said.

“Most of the members of our church are pretty much related, by marriage if not by blood. That cemetery is a sacred place for us.”

For that reason, since the fire, people who have left Opelousas and Greater Union have urged the pastor to rebuild his church on the same hallowed ground.

“As far as I am concerned, that address will always belong to Greater Union Baptist Church. I don’t want to build a cathedral. We don’t have room for that. But I want that land to contain a house of God forever.”

The 66-year-old, who has been pastor of Greater Union for 16 years, said one of his deacons saved a Bible from the charred ruins of the congregation. Richard hopes it’s his, filled with notes about family history and scriptural thoughts, but he’s been too busy to check. A pastor’s first responsibility, he said, is to tend to his flock. And his is grieving.

Asked about the most valuable thing lost in the fire that destroyed his church, Richard said it wasn’t anything tangible. It was trust.

“We are a black Baptist church, and we’ve fellowshipped with some white community members who have come to our church,” the pastor said. “But when the fires started it created an atmosphere of mistrust. The little trust we had was burned up in that fire.”

In Louisiana, as in other Southern states, memories of racial violence and racist policies stay close to the surface, Richard said. It doesn’t take long to recall how the Ku Klux Klan terrorized African-Americans by setting fire to their sacred spaces.

“Our culture has been filled with mistrust and misunderstandings,” the pastor said.

Police say the fires at the three black churches in St. Landry Parish were started by the white son of a sheriff’s deputy who was motivated by black metal music, not racism per se. The accused 21-year-old has pleaded not guilty to charges in the case.

But the fact remains: All three churches were predominantly African-American.

As he prepared for Sunday Easter services, which will be held in a cozy Masonic lodge in Opelousas, Richard said the congregation has already forgiven the “firestarter.” Trust will be harder to rebuild, but he is hopeful.

Richard said he’s been thinking a lot about John’s Gospel, especially the 20th chapter when Mary Magdalene finds Jesus’ empty tomb.

“After witnessing Christ’s crucifixion, it was a traumatic experience for her to go there. And that kind of speaks to us as a congregation, when we realized our church was on fire.

But, as we know, that is not the end of the story.”

‘Notre Dame is still standing!’

Since Notre Dame’s fire, hundreds of people, both Christian and not, have sent “testimonials” about their spiritual and emotional ties to the cathedral. They came in from New Jersey and Seattle, Poland and Japan, Italy, Germany, and, of course, from France.

People recalled the sacred moments of their lives staged in the ancient cathedral: having hasty marriages blessed by Notre Dame priests, hearing the voices of an angelic choir rise through the vaulted arches, watching their children be baptized.

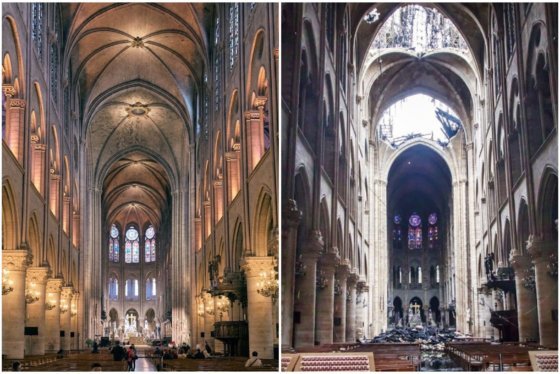

The cause of the fire is still not known, but investigators suspect that it was an unintentional result of repairs at the Gothic masterpiece. Many of its most prized possessions, including the stained-glass rose windows and a crown of thorns believed to have been worn by Jesus, were somehow spared.

Nevertheless, wrote Mother Marie Christine in her testimonial posted on the cathedral’s website, “a whole part of our heritage, our history, has gone up in smoke.”

“And yet, in a few days, another fire will shine in the night opening the solemnity of the solemnities,” Christine wrote, in a sentiment shared by many of the testimonies, “that of the Resurrection of Christ.”

There seemed to be an unspoken assumption that Notre Dame would outlast us, wrote a man named Clemence, just as it had outlasted the Huguenots, French revolutionaries and Nazis who had tried to destroy it.

Parisian priests, too, wrote testimonials about “Our Lady,” as the cathedral was affectionately known among the French.

The Rev. Denis Metzinger, parish priest of Saint-Etienne-du-Mont and a canon of Notre Dame, said that even before the fire, he had been contemplating Jesus’ words upon the cross, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

“I admit that this question has been mounting in me for weeks before the accumulation of scandals of all kinds that have emerged in my family the church in the 21st century,” Metzinger wrote, in an apparent reference to the Catholic Church’s sexual abuse scandal.

Jesus’ question again echoed through the priest’s mind as he watched Notre Dame burn on Tuesday through tears. Metzinger said he was a tour guide at the cathedral, was ordained a priest at Notre Dame and participated for many years in its Masses and other sacred ceremonies.

Like many others, Metzinger said, he took heart in the fact that, when the smoke cleared, Notre Dame’s main altar and the gilded cross above it remained.

“Notre Dame de Paris as the church in our time is disfigured.” he said. “Notre Dame de Paris as the church in our time is standing!”

Serenading ‘Our Lady’

On the day after the fire at Notre Dame Cathedral, John Cavadini, a professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, said a special prayer for the cathedral and put on his fleur-de-lis tie.

As its name suggests, the university has French roots. It was founded by a French missionary order, the Congregation of Holy Cross.

Tuesday morning, Cavadini talked to one of his classes about why the fire at Notre Dame Cathedral seemed to so deeply affect people around the world, Christians and atheists alike.

Somehow, the flames seem to have fanned a latent spiritual impulse among even the most secular-minded, he said.

“I don’t think people would have had that reaction if Notre Dame were not a church,” he said. “If it were the Louvre Museum or even the Vatican Museum, people would have been upset, but not like this.”

Cavadini said he saw faculty members with tears in their eyes after watching the inferno tear down the cathedral’s spire.

“That fire seems to have unleashed a kind of kinetic energy,” the professor continued.

“The cathedral served as an embodiment of our spiritual ideals, and people took it for granted that it would always be there. When it collapsed, it was as if something inside of us collapsed as well.”

In the days after the Notre Dame fire, many commentators referred to the cathedral, and others like it that had stood for centuries, as “monuments to resilience” or “testaments of faith.”

That’s true to an extent.

But watching the crowd of Parisians serenade their burning cathedral Tuesday night with “Ave Maria,” a hymn about St. Mary, the idea arose that any church, even a cathedral, is only a monument to faith. They are expressions of a human longing for the sacred and the spiritual, but they are not the longing itself — and that impulse, if history is any judge, can be much more difficult to destroy.

Or, as Pastor Richard said more succinctly, “Our faith isn’t in any building. Our faith is in us.”