Mapping Asian American history in the nation’s capital

![<p><strong>Union Market</strong></p>

<p>Union Market, formerly Florida Market, has been supplying food products to D.C. businesses and residents since 1931.</p>

<p>“Asians really started going in there and setting up retail and wholesale businesses in the 1970s,” Sojin Kim, curator with the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, said. “The first Korean business to go in there [was when] Sang Oh Choi and his brothers set up ‘Sam Wang Produce,’ which became one of the biggest wholesalers in the city by the 1980s.”</p>

<p>From the 1970s through the 1990s, Kim said most of the proprietors in Union Market were Asian immigrants.</p>

<p>“They were servicing the entire city, both with produce and products that Asian retailers or restaurants might want, but also the place where street vendors can buy tchotchkes and souvenirs,” she said.</p>](https://wtop.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/unionmarket-1.jpg) 1/5

1/5

In the 1970s, Asian businesses started populating Union Market, including here on the 1200 block of Fourth Street NE.

(Courtesy Sojin Kim)

Union Market

Union Market, formerly Florida Market, has been supplying food products to D.C. businesses and residents since 1931.

“Asians really started going in there and setting up retail and wholesale businesses in the 1970s,” Sojin Kim, curator with the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, said. “The first Korean business to go in there [was when] Sang Oh Choi and his brothers set up ‘Sam Wang Produce,’ which became one of the biggest wholesalers in the city by the 1980s.”

From the 1970s through the 1990s, Kim said most of the proprietors in Union Market were Asian immigrants.

“They were servicing the entire city, both with produce and products that Asian retailers or restaurants might want, but also the place where street vendors can buy tchotchkes and souvenirs,” she said.

2/5

2/5

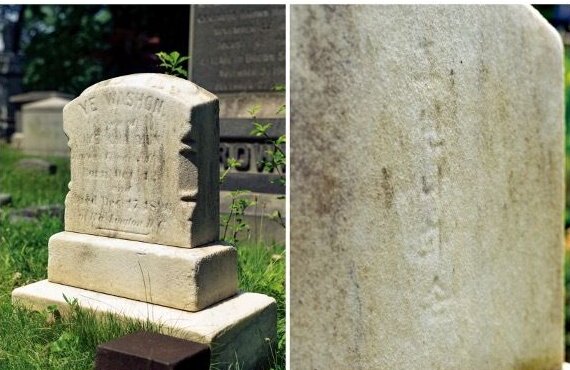

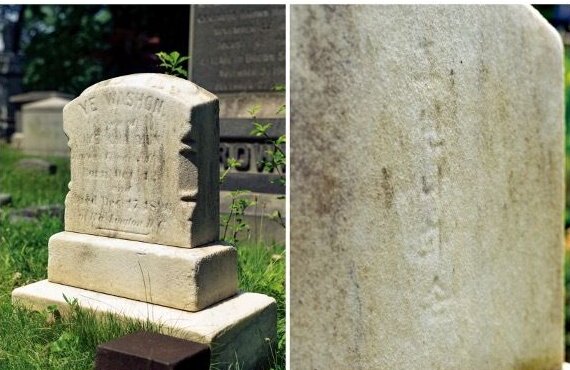

The headstone for Washon Ye is located at Oakhill Cemetery in Georgetown.

(Courtesy Collection of the Old Korean Legation Museum)

Washon Ye headstone

Washon Ye is believed to be the first Korean to be born in the United States on Oct. 12, 1890, according to the curators.

He was the son of Ye Cha Yun, the fourth minister to the Korean Legation in D.C.

“He was born in October 1890 and baptized at the Church of the Covenant at N Street and Connecticut Avenue, ” Kim said. “He was named Washon specifically because he was born in Washington, D.C. — so he was named for the city in which he was born.”

Sadly, the boy died when he was two months old, “and he’s buried in Oakhill Cemetery in Georgetown.”

Ted Gong, executive director with the 1882 Foundation, said Chinese Exclusion Laws enacted in 1882 prohibited Chinese people from immigrating to the U.S. and barred them from citizenships.

The Korean experience was similar, Gong said, so Washon Ye’s role was significant: “First generations coming in, getting settled, trying to survive here, and produce a next generation.”

3/5

3/5

The first Korean Church in Washington was located at Foundry Methodist Church at 1500 16th St. NW.

(Courtesy Carol Kim Retka)

First Korean Church

“A lot, but not all, of the Korean immigrants who’ve come to the United States are Christian,” Kim said. “And, many of the pathways to immigration for Koreans came through relationships with missionaries or American Christian educators.”

In 1950, several dozen Koreans in D.C. “decided they wanted to get together and form a congregation so they could provide one another with support and prayer during the Korean War,” said Kim.

It wasn’t clear where the congregation would meet.

“The Foundry Methodist Church — even though most of these people are Presbyterian — welcomed them to use one of the chapels in the church on 16th Street from 1951 through 1978,” said Kim.

It later developed into the Korean United Methodist Church of Greater Washington, which is now based in McLean, Virginia, according to the map curators.

4/5

4/5

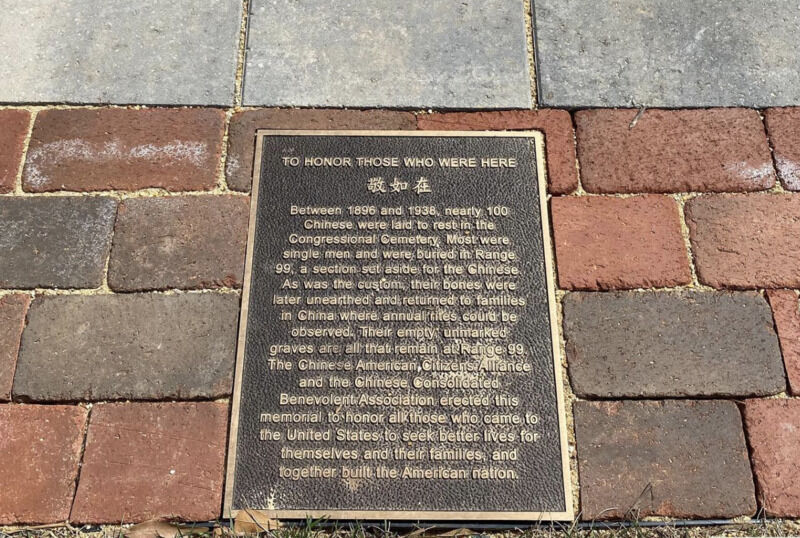

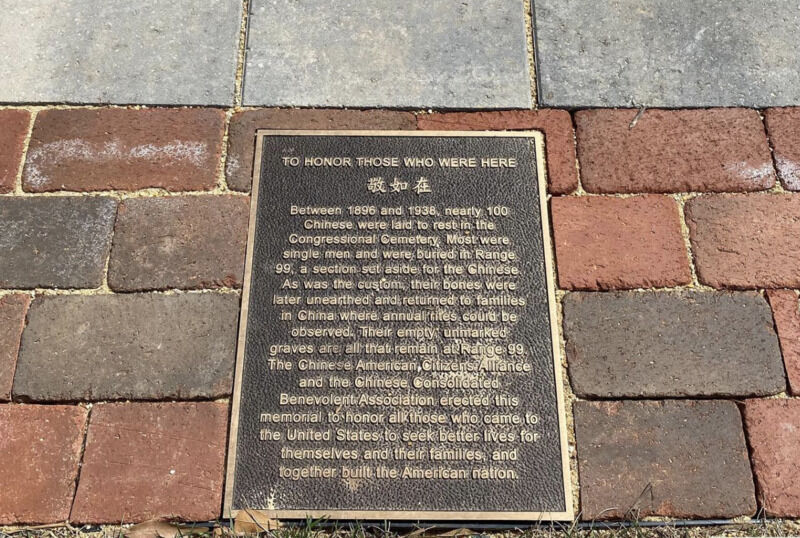

Range 99 at Congressional Cemetery was a temporary resting spot for approximately 100 Chinese people in D.C.

(Courtesy Wei N. Gan)

Range 99 at Congressional Cemetery

Congressional Cemetery, at 18th and E streets SE near the Anacostia River, was the final resting spot for a wide variety of Americans, including Civil War soldiers from both the North and the South, approximately 100 U.S. senators and representatives, Dolly Madison and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover.

Between 1896 and 1938, nearly 100 Chinese residents were laid to rest in Range 99 in the Congressional Cemetery, according to the plaque currently there.

Ted Gong of the 1882 Project said it wasn’t because of segregation. Initially, most of the Chinese immigrants to the United States were bachelors, Gong said.

When a Chinese immigrant died in the U.S., it was considered an obligation to have the loved ones’ remains shipped back to their home village, where the family, clan or territory association could continue traditional rites.

“The tradition at the time was if you died in the U.S., your family association or territory association would exhume you after about 10 years,” Gong said. “Your bones would be collected in a prescribed way and shipped back to your home village.”

No bones from Chinese immigrants remain in Congressional Cemetery, although cenotaphs — memorials to people buried elsewhere — are present, along with the plaque describing Range 99.

5/5

5/5

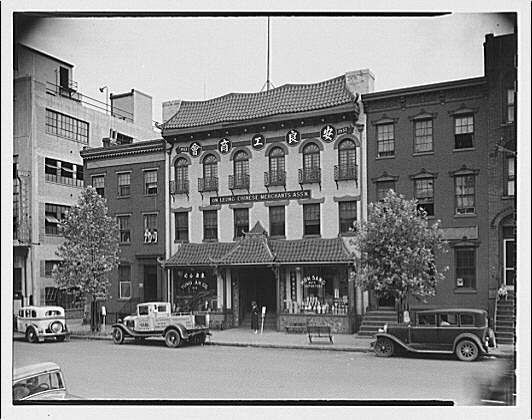

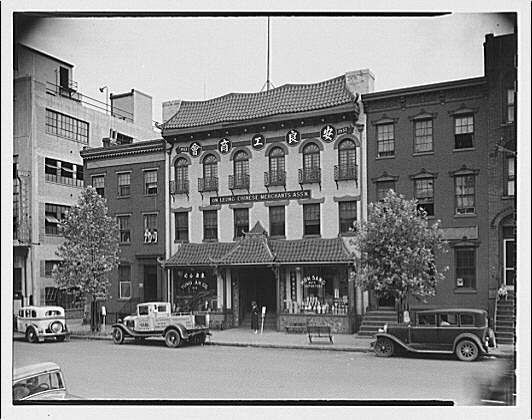

The On Leong Chinese Merchants Association played a major role in the move to D.C.’s current Chinatown.

(Courtesy Library of Congress)

On Leong Chinese Merchants Association building

While most are familiar with D.C.’s current Chinatown on H Street NW, many don’t realize it’s not the District’s first Chinatown.

In 1851, the first documented Chinese person registered an address on Pennsylvania Avenue. His name was Chiang Kai. Over the next several decades, D.C.’s original Chinatown became established along Pennsylvania Avenue near Third Street NW.

“When the Federal Triangle development was going on, by the late 1930s, the Chinese merchants and other people over there had to relocate,” said Gong.

D.C.’s preeminent Chinese Benevolent Association was called “On Leong Tong.” It provided legal and social services and functioned as a board of trade.

The merchant association relocated to the On Leong building on H Street NW by 1857.

“Other people, seeing this leading organization move into this H Street area, followed, and that’s where we established the current Chinatown,” said Gong.

The “Finding Asian American History in Washington, D.C.” tour is one of 59 listed on the D.C. Historic Sites page, curated by the D.C. Preservation League.

Get breaking news and daily headlines delivered to your email inbox by signing up here.

© 2024 WTOP. All Rights Reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.

Neal Augenstein

Neal Augenstein has been a general assignment reporter with WTOP since 1997. He says he looks forward to coming to work every day, even though that means waking up at 3:30 a.m.

![<p><strong>Union Market</strong></p>

<p>Union Market, formerly Florida Market, has been supplying food products to D.C. businesses and residents since 1931.</p>

<p>“Asians really started going in there and setting up retail and wholesale businesses in the 1970s,” Sojin Kim, curator with the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, said. “The first Korean business to go in there [was when] Sang Oh Choi and his brothers set up ‘Sam Wang Produce,’ which became one of the biggest wholesalers in the city by the 1980s.”</p>

<p>From the 1970s through the 1990s, Kim said most of the proprietors in Union Market were Asian immigrants.</p>

<p>“They were servicing the entire city, both with produce and products that Asian retailers or restaurants might want, but also the place where street vendors can buy tchotchkes and souvenirs,” she said.</p>](https://wtop.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/unionmarket-1.jpg)