Hear our full chat on my podcast “Beyond the Fame with Jason Fraley.”

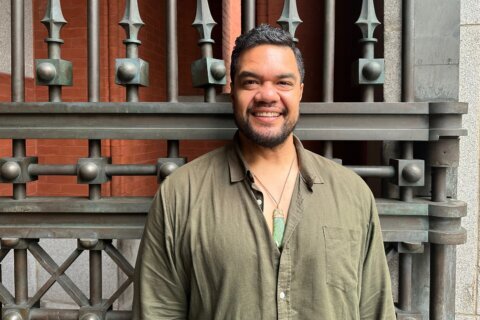

In 2021, Richmond, Virginia, native and American University graduate Jai Jamison, landed his dream job as a Hollywood staff writer on TV’s “Superman & Lois,” which is currently airing its third season on The CW.

On May 2 of this year, that job temporarily halted due to the Writers Guild of America strike, with writers claiming that they are receiving unfair compensation from the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers.

“It’s definitely been an interesting couple of weeks,” Jamison told WTOP. “When we got the word that the AMPTP walked away from negotiations without giving a serious offer or addressing a lot of our very serious demands or concerns, it was like, alright, let’s gear up and get out there and start fighting for what we believe we deserve.”

When WTOP initially reached out for an interview, Jamison was busy marching with his fellow WGA members. Writers and their allies have spent the past few weeks picketing, carrying signs and honking horns outside of Hollywood’s top studios, shutting down productions in solidarity with longtime labor unions, including the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) and International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE).

“These studios have been making billions of dollars on streaming and network television and our ask is just 2% of their profits — something that I don’t think is unreasonable at all,” Jamison said. “We start with a blank page, a kernel of an idea, then it’s up to us to create the document or blueprint that then employs hundreds and thousands of other workers, but you can’t do any of that if you don’t have a script. We’re just asking for a share in the profits.”

The WGA previously went on strike for 21 weeks in 1960, three and a half months in 1973, three months in 1981, two weeks in 1985, a record 22 weeks in 1988, and most recently, 14 weeks from 2007 to 2008. Throughout those efforts, writers secured rights to be paid certain residuals by traditional studios — but the recent streaming revolution by Silicon Valley changed everything, turning Hollywood into a new Wild West of unwritten rules.

“It comes down to streaming,” Jamison said. “These tech companies that have come in, the Netflixes of the world disrupted the way things have worked for 100 years. … We get some residuals, but it’s not the same as what we’d get from network or releasing in theaters. Part of what we’re fighting for is transparency of data to understand what shows people are watching and, if there’s a hit, we share in the success of a hit.”

Gone are the days of judging a film’s success by box-office gross. During the pandemic, studios experimented with day-and-date releases, dropping a Warner Bros. film on HBO Max, Paramount film on Paramount+, MGM film on Amazon Prime or Walt Disney film on Disney+ the same day as theaters. As the pandemic subsided, studios shifted to a 45-day window, while Amazon and Apple recently pledged $1 billion to release theatrically first.

“It used to be that if a movie went to the theaters and it made hundreds of millions of dollars, the people who helped create that movie got to share in those profits,” Jamison said. “Now, if a movie goes straight to a streamer and then gets billions of views or whatever metric they want to use to describe if something is a hit or not, we get the same very small base of residuals. We don’t know. We don’t know what’s successful and what’s not.”

As for television, the old writers’ dream of going into syndication barely exists anymore.

“On network television, if you wrote a script and it re-ran you would get a percentage of that script fee again,” Jamison said. “It would be enough where if you’re between jobs or you’re developing something … it’s enough to keep you going. It’s enough to create a middle class of writers where you’re not struggling between gigs. Now when those same shows go online for streaming, it’s pennies on the dollar in terms of what you used to get.”

In the early streaming days, streaming platforms like Netflix or Hulu would pay licensing fees to air shows created by other studios. Today, they create their own original content, keeping it all in-house with little transparency.

“Early on in the new streaming world, they would license,” Jamison said. “People who had those residual points would get some money from the licensing, but now that all of these streamers have vertical integration of their own original content, there’s no market for licensing. They’re selling to themselves at a very low price, so the people who created it, even if they have points for the residuals, you get less and less.”

Another WGA demand is a minimum number of writers per show, proposing a minimum of one writer per episode for six episodes, then adding an extra writer for each two additional episodes up to 12 writers for 22 episodes.

“It allows for the basis of training,” Jamison said. “Television writing is an apprenticeship profession. You go in as a staff writer and you are mentored and taught by the upper-level staff writers until you move up the ranks yourself. You get experience, you learn how to break story, you learn how to go to set and produce your episode, you learn how to take it to editing and do the mix, then you move up and train those who come after you.”

The WGA balks at recent studio attempts to create “mini rooms” with just three upper-level writers working on a freelance basis for cheaper paychecks where they’re not even involved with going on set during production.

“The streamers are trying to turn our profession into a gig economy,” Jamison said. “We’re pushing to codify norms that have been eroded. What these companies come in and do is, without understanding how things are made, they’re just looking for efficiencies, which I get, but you can’t put numbers on the process of television making.”

The WGA is also worried about the sudden prospect of human writers being replaced by artificial intelligence.

“We went into it with the idea of, hey, this is something coming down the pike, let’s put a nail in it, let’s stop it at the head and agree that A.I. is not something we should be doing, but the AMPTP pushed back harder than we thought, so we said, ‘Oh, this is something we should be fighting for, they won’t commit to not replacing us with robots!'” Jamison said. “They’re not concerned with making good shows or art or exploring the human experience.”

While the WGA and AMPTP negotiate, he waits to learn the fate of his show, “Superman & Lois,” which averages 1.2 million viewers over seven days on The CW. According to The Hollywood Reporter, The CW has already canceled “Kung Fu,” “The Winchesters” and “Walker: Independence,” leaving just three shows left on which to make a decision: “All American: Homecoming,” “Gotham Knights” and Jamison’s livelihood of “Superman & Lois.”

“We’re definitely one of the highest rated shows on the network, but we don’t know if we fit into their new strategy,” he said. “We’re still waiting to hear if we’re going to get a season four, I really hope we do, but if The CW doesn’t pick us up, we’re hoping that HBO Max will. We do pretty well on the platform. … We’re hoping we get another season, we have some really fun things planned for a potential season four, but we’ll have to wait and see.”

As for viewers, we are currently missing new episodes of “Saturday Night Live” and late-night talk shows with Jimmy Fallon, Jimmy Kimmel and Stephen Colbert. These shows will instead air re-runs until the strike is over because there are no writers to write the monologues and sketches. Scripted television series will be next.

“Studios do have a certain number of shows in the bank, but a lot of legacy networks, ABC, NBC, CBS, as soon as September, their fall schedules will be impacted,” Jamison said. “The writers rooms for those shows would be starting about now. ‘Abbott Elementary,’ that writers’ room is not going for next season, so we’ll definitely start seeing [gaps] in the fall, depending how long this goes. Streamers will start losing their content early next year.”

In the end, he hopes for a speedy but meaningful resolution to the WGA’s demands.

“Listen, this thing could end tomorrow if the AMPTP comes with a reasonable offer,” Jamison said. “None of us want to be striking, we all want to be working, we all want to be writing, that’s why we got out here to do it, but we also understand that this is an existential threat to our profession and we need to hold the line here because if it keeps eroding there may not be such thing as a WGA in the future, so we understand we need to stand up now.”

Hear our full chat on my podcast “Beyond the Fame with Jason Fraley.”