This video is no longer available.

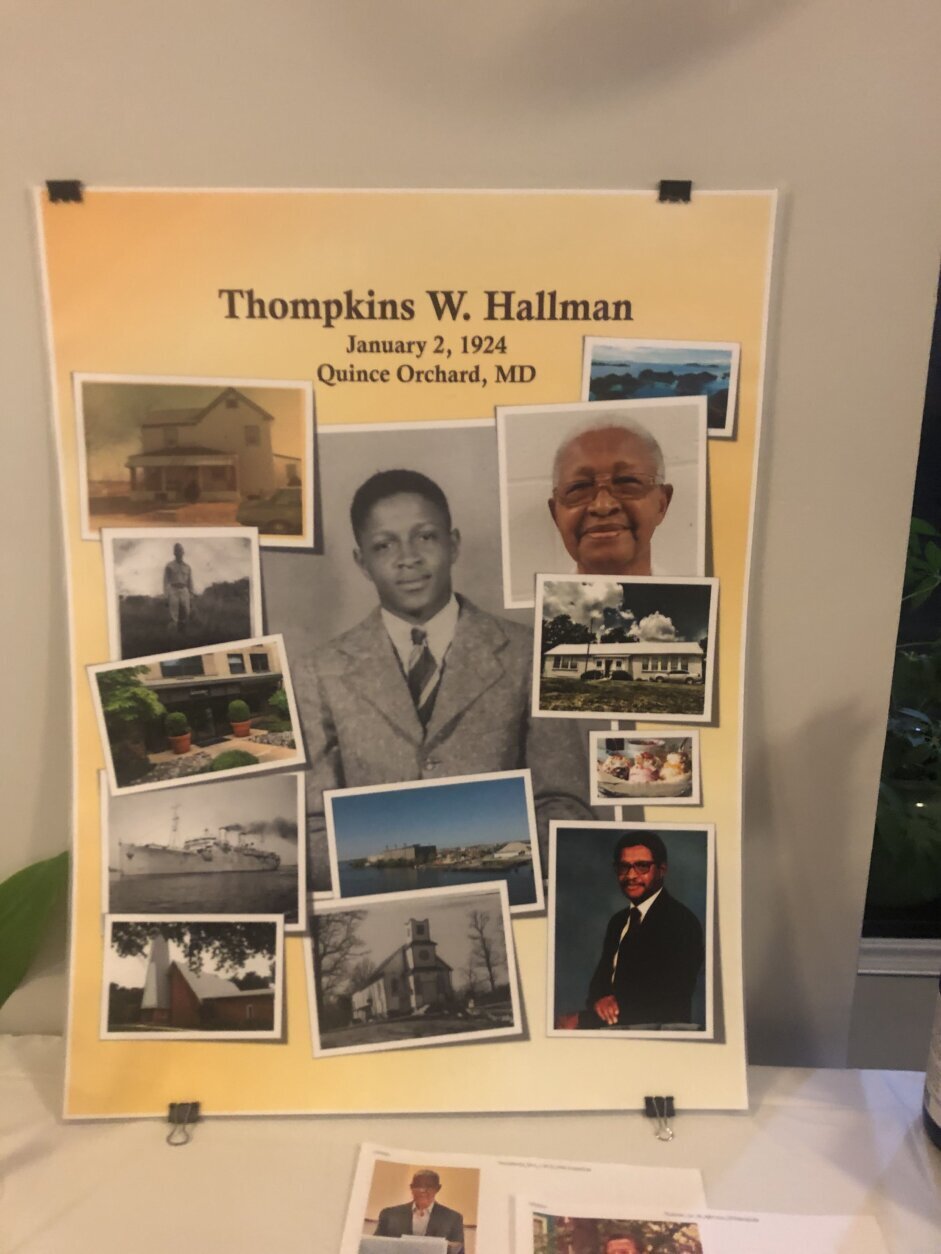

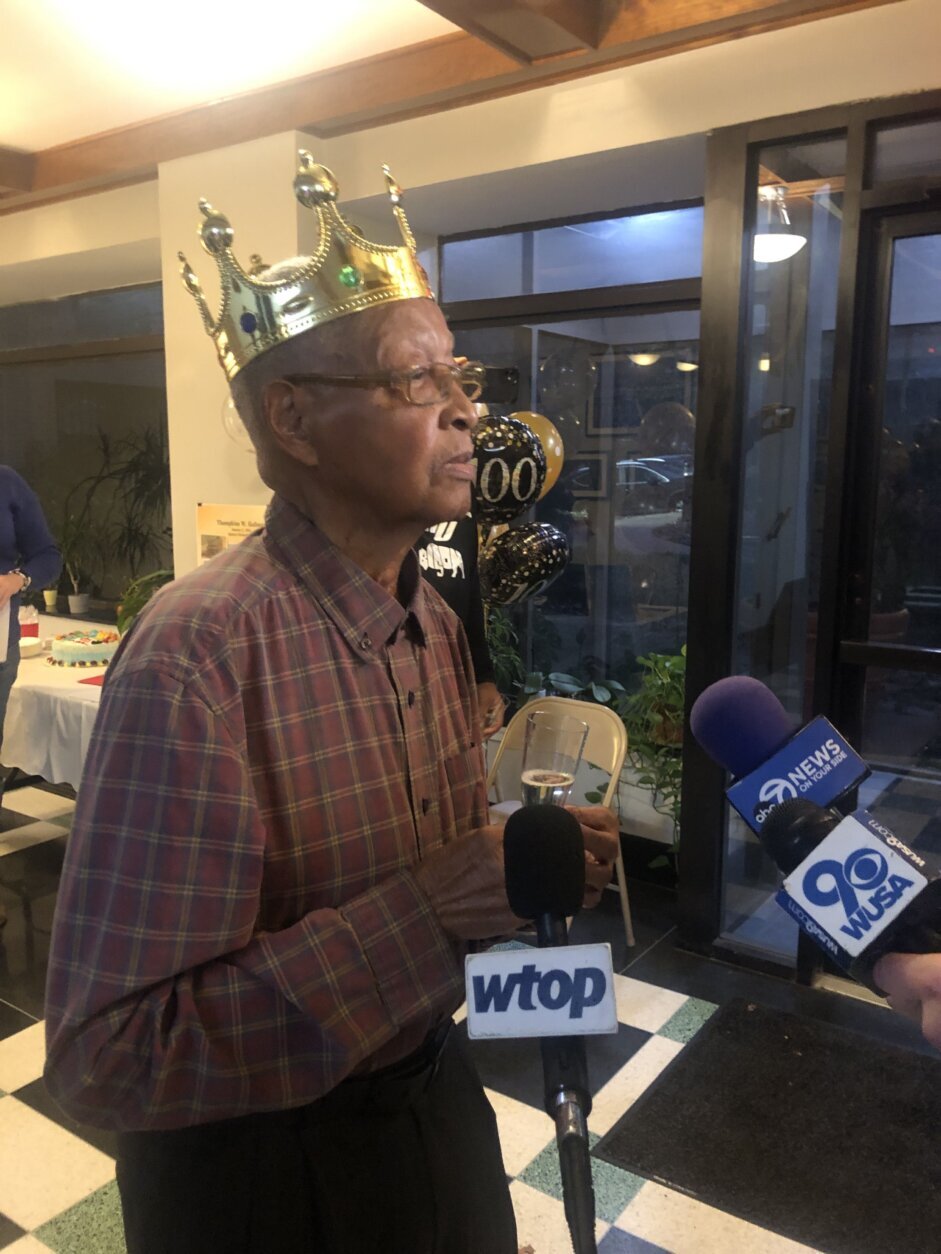

The lobby of a D.C. apartment building was decorated with balloons and streamers, tables were laden with party food and Champagne corks popped, as guests toasted Thompkins Hallman who was born on Jan. 2, 1924.

As his Lanier neighbors inside the seven-story apartment building near Adams Morgan sang happy birthday, the guest of honor bounded down the steps and took his place in the center of the lobby, sporting a cardboard, gold-colored crown atop his head to mark the occasion.

“I take it one day at a time and [do] whatever I decide I want to do. I get up in the morning. I have a bath. I read my Upper Room (a daily devotional) and then I kneel and say a prayer, ‘thank God for a restful night and waking up this morning,'”

Hallman said with a plastic flute of Champagne in his hand. “I have breakfast, I have my black cup of coffee, I read the Washington Post and I’m ready for the day.”

Asked to what he attributes his longevity Hallman answered without hesitation: “Psalm 139,” which is a psalm about an ever-present God.

“He is there when I go out, when I come in, when I stand, when I sit. He knows my thoughts before I speak … God is in control. He knows how long we all live. Some he takes early some he takes late,” Hallman said.

The centenarian still drives twice a week to his long-standing family church, Fairhaven United Methodist Church, in the Quince Orchard community of Gaithersburg in Montgomery County, Maryland. There, on a family farm, Hallman was born.

Hallman is a World War II veteran — having served in the segregated U.S. Army in the Pacific Theater before the U.S. armed forces were desegregated by President Harry Truman in 1948.

He was also an early civil rights, pioneer protesting segregation in public places in D.C., more than a decade before Rosa Parks sparked a Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott in 1955.

“I was involved in 1942 in an organization called the Integration Workshop. It was a part of the Congress of Racial Equality, headquartered in New York,” said Hallman. “I can remember a very segregated city, back in the 1940s. Hotels, restaurants, theaters, all those were segregated downtown,” he said.

Hallman also survived prostate cancer in the 1980s.

“I went to the doctor about two years ago and he said ‘you don’t need to take the shots anymore. There is no sign of cancer there anymore. It’s gone,'” said Hallman, “I guess God said it wasn’t my time to go,” he said.

Hallman is a favorite among the residents in his building.

“He’s just the kindest, gentlest soul that you’ll ever meet. And he shows up at all of our parties. He’s very social. I think he’s lived for a long time because he’s so active and so engaged and so curious,” said Carol Miller who helped organize the party for Hallman.

Get breaking news and daily headlines delivered to your email inbox by signing up here.

© 2024 WTOP. All Rights Reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.