After decades of storing the District’s most historic documents in a building that’s just as old as some of the records inside, the D.C. Archives is headed to a new home.

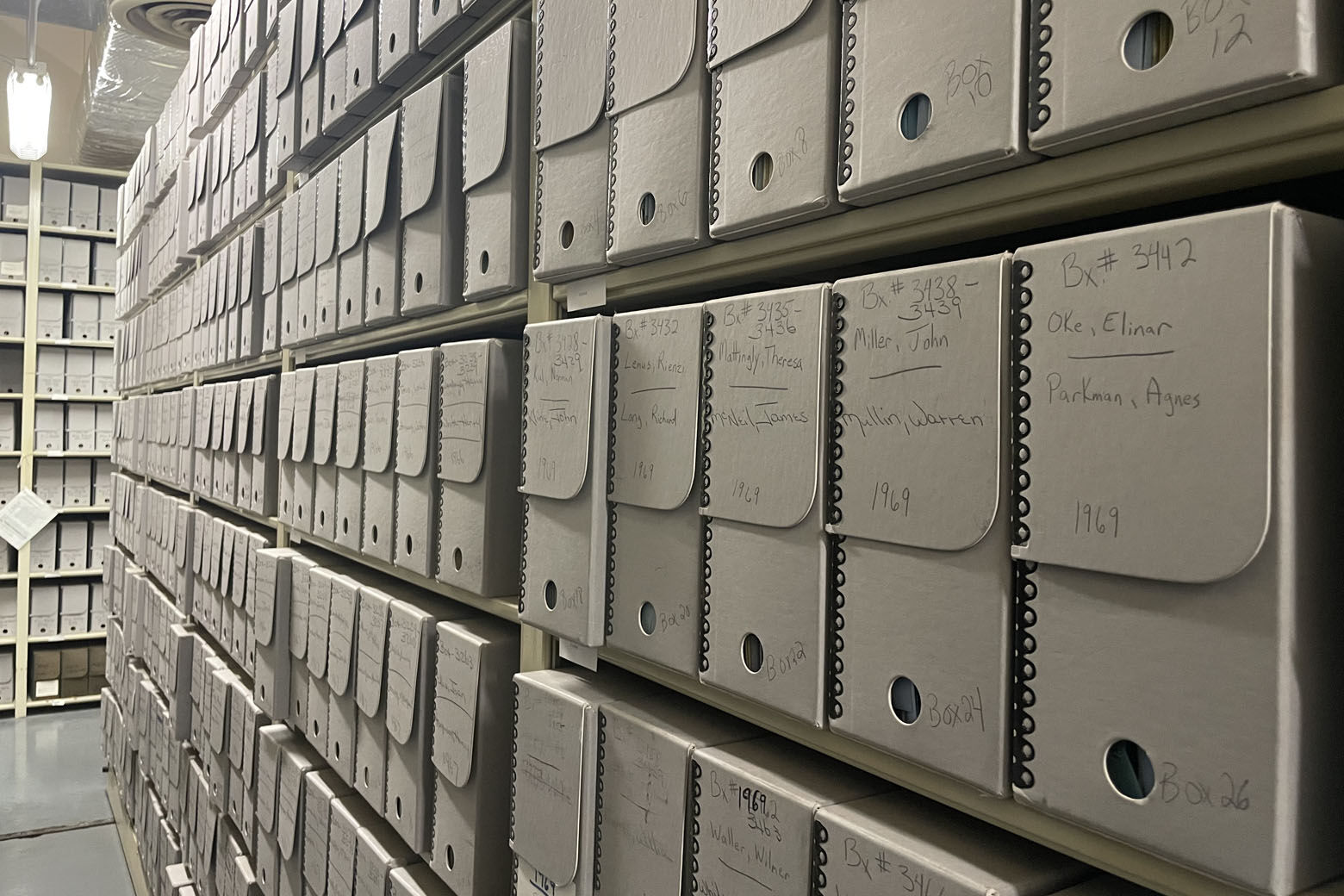

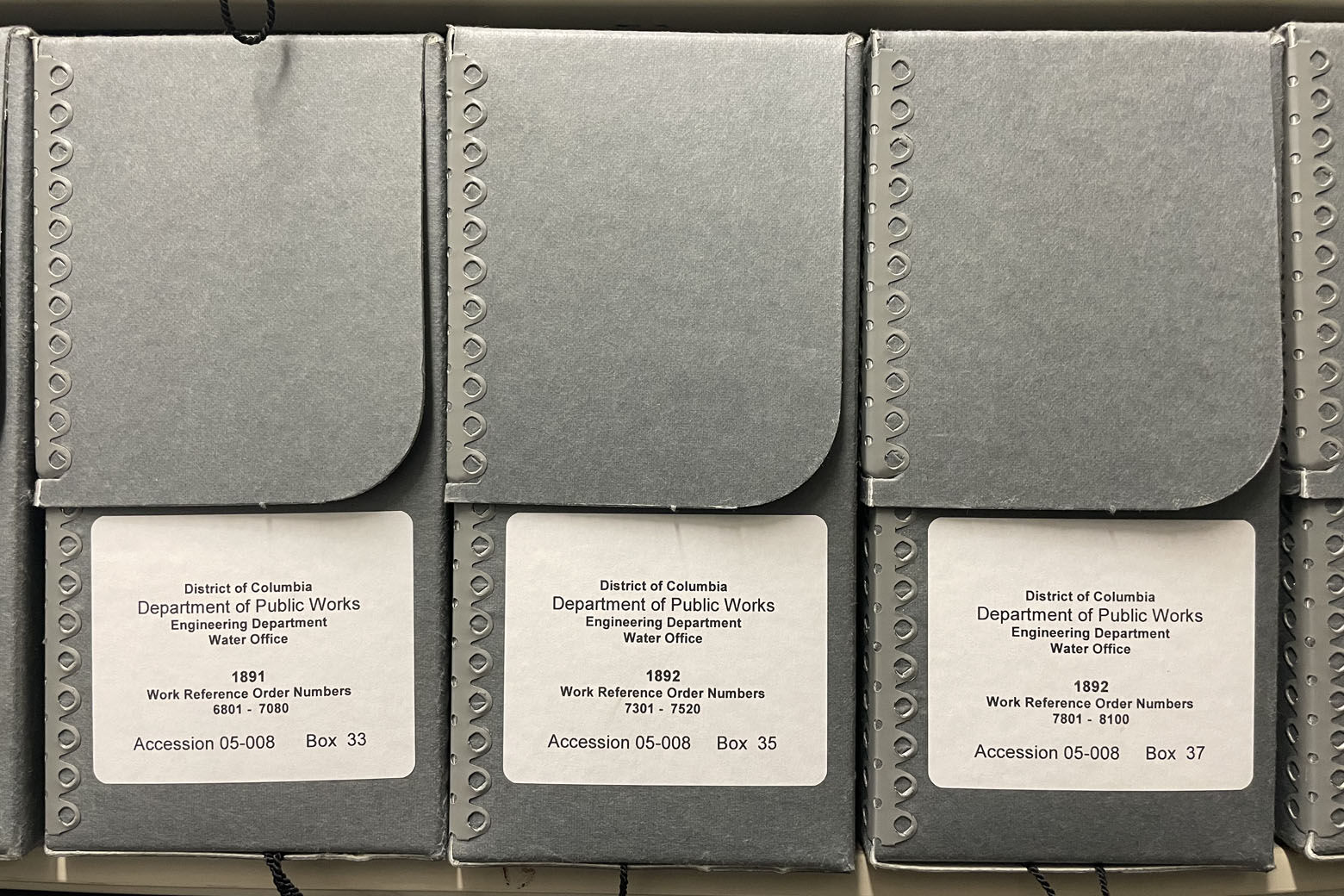

The agency has an impressive collection of documents that go as far back as 1792.

“We have Frederick Douglass’s will, we have Alexander Graham Bell’s will,” Lopez Matthews, Jr., the state archivist and public records administrator at the agency, told WTOP. “Duke Ellington’s birth certificate is also here.”

But those documents are stored in a retrofitted farmhouse that was built in the late 1800s, and space is limited. Some historic records are still housed at the National Archives, Matthews said.

“We have maybe three spaces for research,” he said. “Documents need to be stored at a lower temperature, 65 degrees or lower. They need dark, cool areas. That is something that our new building will do better than this building.”

The city is moving ahead on a new $104 million archives building, slated to open in 2026, on the University of the District of Columbia’s campus in Van Ness. The push to get a new building was primarily spearheaded by historical groups and private donors.

Matthews said Mayor Muriel Bowser and other city leaders have long supported the move, too.

“Their support has been crucial to moving the project forward,” Matthews said.

The head archivist added some items to a wish list for the building. In addition to more space, the new facility will also boast a state-of-the-art digitization lab to preserve old records better.

His team is working on a project to digitize a collection of letters from children to former Mayor Anthony Williams shortly after the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

“They were sending their condolences and sharing their sense of loyalty to the United States,” he said. “They’re a pretty amazing collection of letters. Today they would be around 30 years old. We’re hoping that the people who wrote the letters connect with us and say, ‘Wow! This is a letter I wrote when I was six or seven.’”

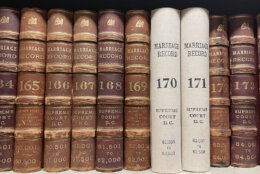

Through D.C.’s oldest documents, Matthews can unveil a slew of life stories from former and current residents — like the love story of a Black couple who were finally able to marry shortly after the Civil War in the late 1860s. The couple had been together for 50 years on their wedding day.

“I just thought how amazing that was that they were able to get married once slavery ended,” he said. “Our records basically document residents’ interaction with the government in any kind of way. You never really realize how much government impacts your life.”