The National Park Service cleared a D.C. park just a block from the White House, where dozens of people had been living in tents in the small green space.

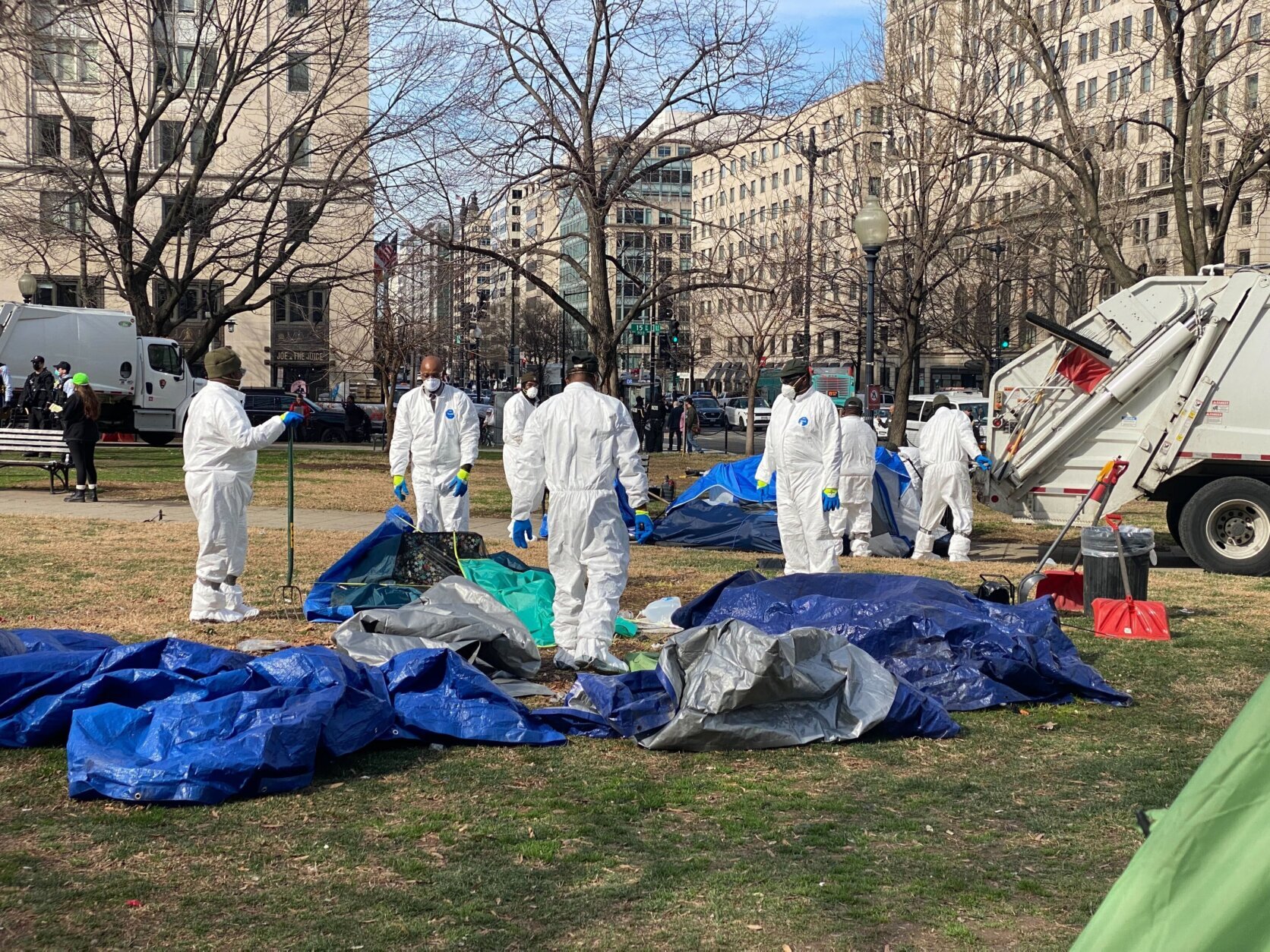

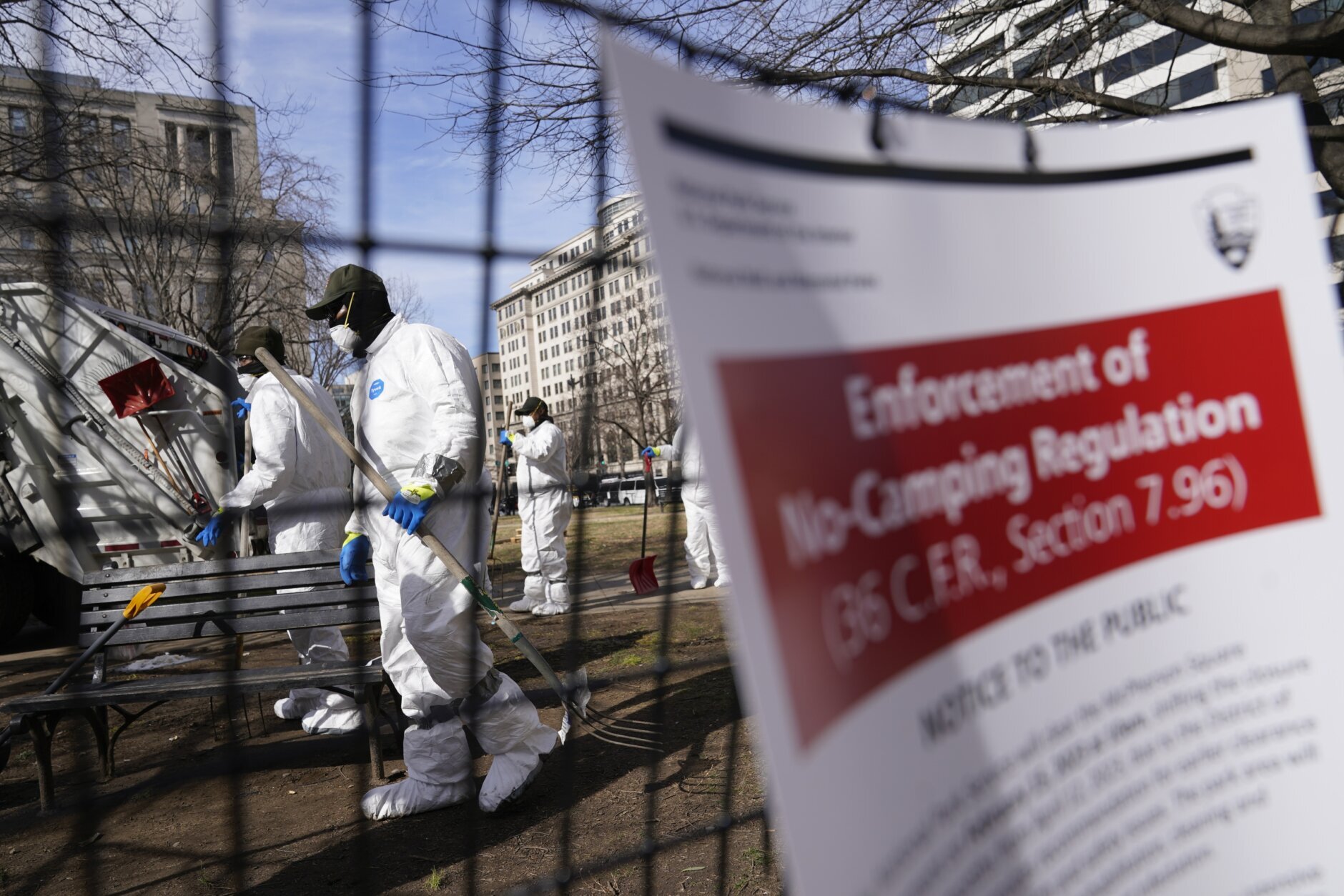

Park Service employees wore white hazmat coveralls as they combed McPherson Square Park on Wednesday morning, filling garbage trucks with tents and trash left behind. Police sealed off the park and repeatedly announced over a loudspeaker that those who refused to leave would risk arrest.

As crews were putting one tent in a garbage truck, the bottom fell out, spilling trash along with numerous rats that scurried to find new hiding spots.

More than 70 unhoused people were living in the tent city by the time the Park Service had requested to move up the clear-out date from its original April plan after Wayne Turnage, the deputy mayor for health and human services, said the encampment was an imminent public health hazard.

Anne Oliva, with the National Alliance to End Homelessness, said that most people left before the clearing date.

“Folks have already left, and we don’t know where they’ve gone. They’ve gone to places where maybe their outreach worker can’t connect with them as easily anymore,” Oliva said. “They’re going to have to go find them again; they have been betrayed yet again by the people who are really supposed to be helping them.”

Mayor Muriel Bowser, speaking about the street cleaning, called conditions unsafe and unsanitary and asked that individuals avoid saying that services aren’t being promoted by the city.

“People who find themselves in a homeless encampment oftentimes have many hurdles to get over that make connecting to services difficult,” Bowser said. “So no one should promote the idea that we’re not trying to connect people to services or the abundance of housing assistance in the D.C. area.”

Despite her comments, calling for the city to “do better than McPherson” after a number of drug-related deaths and bolstering the decision to speed up the encampment removal, housing assistance issues continue to be among the District’s housing controversies.

Among those dealing with these issues are some campers who remained until the very end, such as Daniel Kingerly who has lived in the park for some three years.

“So here we are working on the homeless again,” said Kingerly, who said it was their constitutional right to use public land.

The square was ordered to be cleared by the National Park Service at the request of the D.C. Office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services after learning about three recent drug overdose deaths at the square.

“The District requested that the National Park Service (NPS) close the encampment earlier out of concern for health and safety and given that the growth of the encampment was impeding effective social service engagement,” National Park Service spokesperson Mike Litterest said in a statement.

NPS notified square inhabitants in October of the plans to clear the park of any encampment on April 15. Two weeks ago, they moved up the date because of the recent deaths.

“How many overdose deaths have there been in the entire city? They don’t close the city now. How many acts of violence have happened throughout the city? Not closing the city down,” Kingerly said.

Oliva said that instead of clearing the camp, they should provide more security to prevent violent crime and drug use. Other housing activists say a government program that offers vouchers for subsidized apartments would be appreciated among the unhoused.

“I actually was here one morning when somebody passed away,” Oliva said. “Nobody wants people to be forced to live in these kinds of conditions. But until they can be connected to the housing and services that they need to end their homelessness, the alternative should be to try and make this as safe a place as possible.”

In a statement, NPS said it met with the National Coalition for Housing Justice and other federal agencies to have a compassionate-focused plan for closure.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.