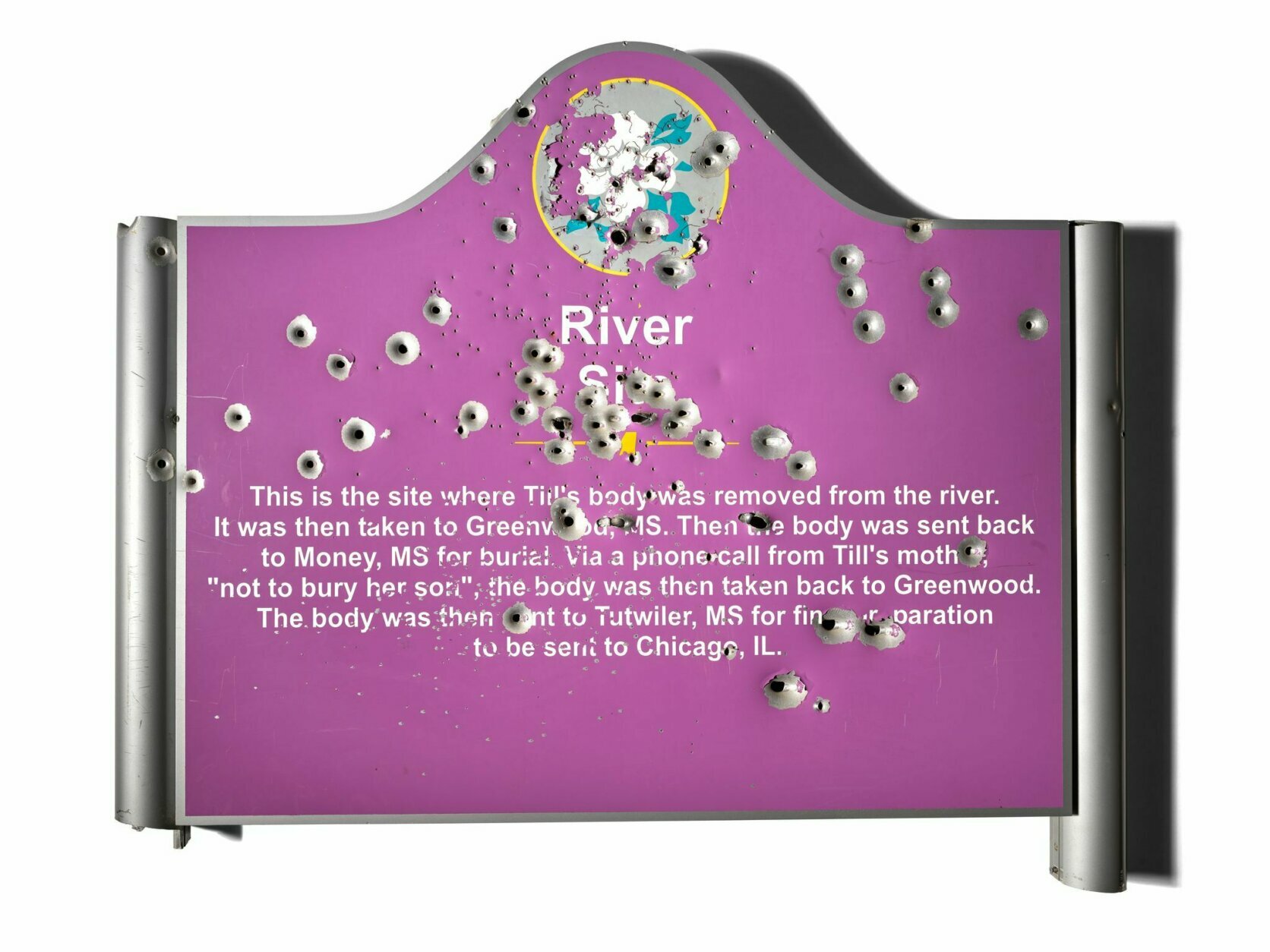

A bullet-riddled sign marking the spot where police pulled Emmett Till’s body out of a Mississippi river is on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in D.C.

Curators unveiled the monthlong exhibit this week.

“Why is it so hard to commemorate the memory of a 14-year-old Black boy?” said Tsione Wolde-Michael, curator of African American Social Justice division at the museum. She said that’s the question the exhibit, which sits in Flag Hall, asks visitors.

The display is called “Reckoning with Remembrance: History, Injustice and the Murder of Emmett Till.”

In 1955, the teenager was on vacation visiting his uncle in Money, Mississippi. Two men were accused of kidnapping him from his uncle’s home and lynching him. Three days later, police recovered his body from the Tallahatchie River.

The men were acquitted by an all-white jury.

Till’s death sparked the nation’s budding civil rights movement.

Then in 2008, the Emmett Till Memorial Commission erected nine historic markers to remember and honor the teen. One of them was the river discovery. The signs have been vandalized and replaced several time.

The sign on display at the Smithsonian was lent by the commission, and it has 317 bullet holes in it.

“We’re connecting this past of anti-Black violence and bringing it into the present,” Wolde-Michael said. “What those 317 bullet holes show is that every single one of those is an attack against national memory.”

Museum curators said the exhibit has a twofold mission: cement the teen’s story in U.S. history, and get people talking about current anti-Black violence.

“Those signs lay bare the ongoing nature of anti-Black violence,” said Wolde-Michael. “If we don’t get this … we don’t get the full picture of our history.”