After the discovery of a botched firearms analysis at the D.C. Department of Forensic Sciences led federal prosecutors to review ballistics evidence in dozens of other open cases, the director of the lab told WTOP that her department runs “a darn good lab,” and its results can be trusted.

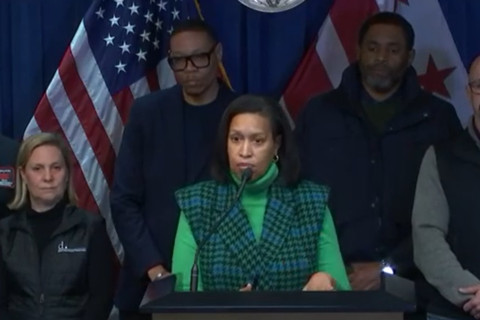

In an exclusive interview with WTOP, Jenifer Smith, director of the D.C. Department of Forensic Sciences, added that while most crime labs across the country are situated within law enforcement agencies, D.C.’s was set up to be independent.

“This is what independence looks like. This is what it feels like,” Smith said, of the relationship between her lab and federal prosecutors, who recently took the lab to court over the release of documents relating to the error.

Speaking from the lab’s headquarters in Southwest D.C., Smith admitted the lab made an error that was initially flagged by prosecutors in January. A DFS examiner, working in 2017, had wrongly concluded that two cartridge casings from two different crime scenes were fired by the same gun. The analysis resulted in a murder indictment that is now being challenged.

Smith told WTOP the error was caused by a “Black Swan”-type event. She said the examiner, who left the agency in 2019, uploaded the wrong photograph into her casefile, depicting two cartridge casings that were, in fact, a match.

The discovery of that error led to a series of new safeguards in the lab’s Firearms Examination Unit — which Smith said have been “blessed” by outside auditors responsible for renewing the lab’s accreditation to continue performing its work, as well as the department’s internal Scientific Advisory Board, made up of top experts in the forensic science field.

After the discovery of the error, however, prosecutors opened a probe into dozens of other cases, and in several of them, the outside experts retained by the U.S. Attorney’s Office reached different conclusions than the lab’s examiners: The outside examiners were able to match bullets or cartridge casings to each other or to a particular firearm, whereas DFS examiners had rendered a different finding — “inconclusive.”

Smith said the different outcomes are an example of the “gray area” in the forensic science fields of pattern matching, which relies on experts examining and comparing microscopic differences under a microscope.

“What we found, when we looked at those five cases, our examiners were always sort of in this more conservative area, whereas the independent examiner was always calling a match,” she said.

Smith also suggested prosecutors would naturally be dissatisfied with analyses that make it harder to make their cases in court.

“’What do you mean you’re inconclusive?’ … That is a classic response we’re going to get from an investigator or a prosecutor because they want some decision,” Smith said. “They don’t like that gray area. But, in our world, there is room for gray.”

The lab stands by its conclusions in those cases, Smith said.

‘There isn’t some horrible fight going on’

As robberies, assaults and murders involving firearms increased in D.C. over the course of 2020, two of the key players in the investigation of crimes in the District — the Department of Forensic Services and the U.S. Attorney’s Office — have been at odds for much of the year over the lab’s analysis of firearms evidence.

In the case involving the botched analysis, prosecutors over the summer sought a trove of documents from the lab explaining how the error happened and how lab personnel reacted to fix it. The agency resisted turning them over, leading to a dispute in D.C. Superior Court that lasted most of the summer.

The judge in the documents case called the tug of war between the two agencies a “side battle at minimum,” and even the lab’s lawyer in the case, Robert Trout, referred to “hyperventilated rhetoric on both sides.”

Speaking to WTOP last week, Smith sought to ratchet down the tensions.

“I just want to be real clear. There isn’t some horrible fight going on” between the two agencies, she said.

She said she views D.C. Superior Court Judge Todd Edelman’s Nov. 10 decision ordering her agency to hand over only about half of the documents sought by prosecutors as actually buttressing the lab’s independence, helping make “a little bit more clear that there will be some documents, there will be information, that we are allowed to maintain as an independent agency,” Smith said.

The idea of independence played a key role in the creation of the lab in 2011, Smith said, which came just a few years after a groundbreaking 2009 report from the National Academy of Sciences aimed at improving the field of forensic science.

At the time, there was concern about unintentional bias at forensic crime labs creeping in from a too cozy relationship with police departments and prosecutors’ offices, Smith said.

“It was clearly a red flag,” she said, and it came just as D.C. was seeking to create its own crime lab. “And as they were talking about building a new laboratory, they decided to create this independent agency in light of that.”

Smith, a retired FBI agent and DNA analyst who worked the Unabomber case and the DNA collection involving President Bill Clinton during the Monica Lewinsky investigation, said the lab’s independence sometimes puts it at cross-purposes with prosecutors.

As Smith sees it, they’re seeking to make a case; the lab’s role is about following the science wherever it leads.

“When you tell a prosecutor, ‘This isn’t consistent with your theory of the case,’ they are disappointed,” Smith said. “So that isn’t an unusual experience, to be honest.”

Still, the demand for documents came amid rising tensions between the two agencies. The subpoena from the U.S. Attorney’s Office came shortly after prosecutors announced their intent to “audit” the lab with a focus on the 2017 error — and several months after the same prosecutor’s office had asked the FBI and the Justice Department’s public corruption unit to investigate a separate whistleblower complaint over practices at the lab. (The FBI finished its investigation in January and did not recommend any criminal charges).

In court documents, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for D.C. has positioned its ongoing ballistics review as similar to a 2014-2015 audit of how the lab was processing DNA evidence — a review that ultimately led to a temporary suspension of the lab’s DNA casework.

“This is so not the DNA thing. Trust me — I was brought in for the DNA thing. I know the DNA thing very well,” Smith said, referring to her appointment as the director of the lab after the former head stepped down in 2015 in the wake of the controversy.

“We are not the same agency that we were in 2015 for many reasons, through the help of many, many people, including the 200-and-some people who work here,” she said, adding, “You can trust this laboratory.”

The agency has the backing of Mayor Muriel Bowser, who is “heavily invested in how this laboratory operates,” Smith said. “She pays attention to what we’re doing and, I think, she continues to trust in what we’re doing, because I probably wouldn’t be here if she didn’t.”

‘We’re human beings here’

Nearly a year later and hundreds of pages of competing legal motions and documents in between, it’s now settled that two separate ballistics analyses by DFS in 2016 and 2017, linking two cartridge casings from two separate killings, were faulty. The link helped support murder indictments against two D.C. men, Joseph Brown and Rondell McLeod, whose cases are still wending their way through the D.C. court system.

Smith said the lab has no problem admitting error when it’s at fault.

“Clearly, we accept we’re human beings here and that there are going to be times when an issue comes up, and we’re going to do everything we can to try to address that and make it so it doesn’t happen in the future,” Smith said.

Prosecutors discovered the error in January, when they were preparing to take the case to trial and had the evidence reexamined by an outside expert. That expert came to the exact opposite conclusion as the lab’s: The two cartridge casings were not fired by the same gun.

Prosecutors also took issue with how the lab reacted when it was alerted to the error in the case, according to court papers. When the lab was first notified of the outside examiner’s report concluding that the shell casings were not a match, officials first insisted the outside expert must have analyzed the wrong evidence. Smith then blamed prosecutors’ decision to rework cases for introducing new errors in the process.

Smith told WTOP that because the original DFS examiner had included the wrong photo in the casefile — and the actual physical evidence in the case was still held by the outside examiner — the lab initially thought there had in fact been an evidence mix-up. As for the hasty response, Smith pointed to agency rules that require the lab to respond in a timely manner to any complaints raised.

“Because we knew that they thought [we] had a mistake, that concerned us,” Smith said. But because of the spurious photo in the casefile, it wasn’t immediately clear what the issue was. “It also concerned us because we couldn’t see it … It’s like, OK, we have this rule, we have to get back to you, we can’t dilly-dally around. We aren’t seeing it.”

When the evidence was finally sent back to DFS in April, supervisors in the lab’s Firearms Examination Unit dug in and discovered the error for themselves. The lab wrote to prosecutors in May agreeing the original analysis was flawed.

Still, Smith said, it took the lab time to get to the bottom of the error — and it ultimately sent in for reinforcements.

Smith said the lab asked the American National Standards Institute’s National Accreditation Board, known as ANAB, to take a top-to-bottom review of the firearms unit as part of the regular auditing process through which the lab is accredited.

Smith said the ANAB auditors spent a week at the lab over the summer, interviewing employees, reviewing scores of documents and watching the unit’s examiners at work. At the end, the experts noted a few deficiencies and made suggestions for improvement — all of which the lab agreed to adopt.

Among the reforms undertaken by the lab since the discovery of the error: Examiners are required to add contemporaneous notes and labels to microscopic photographs taken of bullets and shell casings to avoid a similar error in the future, and the independent verification process has been strengthened, adding extra layers of peer reviews, to add extra eyes to the process.

In early October, the board re-accredited the lab.

Unbeknownst to Smith or other members of the lab’s leadership, prosecutors had filed a confidential complaint with ANAB about the lab, which they were also investigating at the same time as they were performing the lab’s regular audit.

In the end, according to Smith, the standards board also closed all complaints raised by prosecutors, including that DFS had failed to properly investigate the erroneous cartridge casing comparison.

‘Audit’ disputed

It was the shell casing error that gave prosecutors the impulse to undertake a broader review of cases. But when exactly that began is still unclear to Smith.

“I don’t, to this day, know when it actually started,” Smith said. Prosecutors have not been forthcoming, she said.

“We’ve never had a problem with any side hiring somebody else to review our cases,” Smith said. But she bristles at the prosecutor’s office calling its re-examination of evidence an audit.

Referring to WTOP’s previous report about the prosecutor’s office’s review of cases, Smith said, “you use the word audit, audit, audit — it’s different from what they actually did, which was a case review. And I know it probably doesn’t matter to most people, but it matters to us in the business.”

While two of the three experts retained by the U.S. Attorney’s Office are experienced firearms examiners, Smith said she hasn’t seen anything to indicate they have any experience performing audits.

“You know, you can’t bless yourself and say ‘I’m now an auditor,’” she said. “I may have all the experience in the world … it does not make me an auditor.”

In the case of the botched cartridge casings analysis, after DFS reexamined the evidence, a supervisor in the firearms unit issued a new report with the lab’s new official finding: Inconclusive, meaning it wasn’t clear whether the casings had been fired from the same gun.

However, that retooled finding still conflicts with the conclusion reached by the outside examiners, who said they could conclusively rule out the same gun being used in both crimes.

And that wasn’t the only case reviewed by prosecutors in which outside examiners apparently reached different conclusions on the evidence.

The gray area

An interim report from the prosecutors’ audit team filed in D.C. Superior Court in August uncovered 11 other cases where outside examiners came to different conclusions than the lab’s examiners.

In each of the cases described in detail in the report — the report didn’t provide details about all 11 cases — outside examiners were able to match bullets or cartridge casings where the lab’s examiners were not.

Smith said differences of opinion — when they aren’t direct contradictions — are simply a part of the nature of some fields of forensic science that rely on pattern matching, such as fingerprints and firearms analysis. Examiners are highly trained and follow a scientific method, but concluding that there is enough evidence to say whether a pair of cartridge casings were fired by the same gun, for example, is a judgment call.

The important thing is that a particular lab has a policy spelling out how calls are to be made and that everyone in the lab follows the same process to make conclusions.

Smith said it’s important that examiners have the option to issue an inconclusive finding.

“We have to give pattern recognition examiners that place to go to when they are inconclusive,” she said. “If we force everyone to be either a match or an exclusion, we’re more likely to have false inclusions, and that’s why this area of inconclusive is actually a good thing … We think of that as a more conservative approach.”

In addition, the lab has recently adopted rules regarding when examiners can conclude bullets or cartridge casings were fired by the same gun or when they rule that out. When they don’t have a gun submitted as evidence that can be used to create test fires for comparison, examiners have to rely on at least two characteristics, or “regions,” on the shell casing or bullet itself to make their final analysis.

“We know what our rules are; that’s what the firearms examiners are trained to do,” Smith said. “We can’t speak for any other independent examiner. There’s always a chance that an independent examiner will have slightly different rules of the road by which they go by to determine when something’s inconclusive or not.”

And in the specific example of the redo of the shell casing comparison, Smith said, the independent standards board ANAB looked at all the lab’s documentation and signed off on a finding of inconclusive.

What now?

Still, is the disagreement between the lab and the outside experts cause for concern?

Not necessarily.

At an Oct. 16 meeting of the lab’s Scientific Advisory Board — which is made up of a group of nine outside experts, including several experts in the field of forensic science — several board members said the differing opinions didn’t necessarily mean DFS has erred, but suggested it certainly merited looking into further as it could be a sign of a troubling pattern.

“It would be really interesting for us if we knew how they were able to make the identification on those particular ones where you determined they were inconclusive, and somehow figure out either they’re just way more aggressive, or you have blind spots in your training and your analysis area,” said John Paul Jones II, a top forensic sciences official with the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

“I just feel like there’s something we can learn here, now that all of this has been documented or discussed, to improve operations going forward for the organization.”

At times sounding a bit exasperated, Smith told board members during the October meeting that the lab had sought unsuccessfully for months to get prosecutors to share more information with the lab about the cases they had reworked and specific notes about their findings.

“We don’t have that information,” Smith said. “I mean, all of this has been provided to us by a report — no notes; we’ve seen nothing from them. I’m telling you, I’ve got nothing except the final reports. And that’s it. So I can’t help you there.”

The interim report from the U.S. Attorney’s audit team, which lays out the differing findings in the 11 additional cases, is just five pages long and doesn’t include notes or documentation.

“We will certainly invite the United States Attorney’s Office to share additional information,” she told board members. “But I didn’t want it to go without saying that we have asked and asked and asked.”