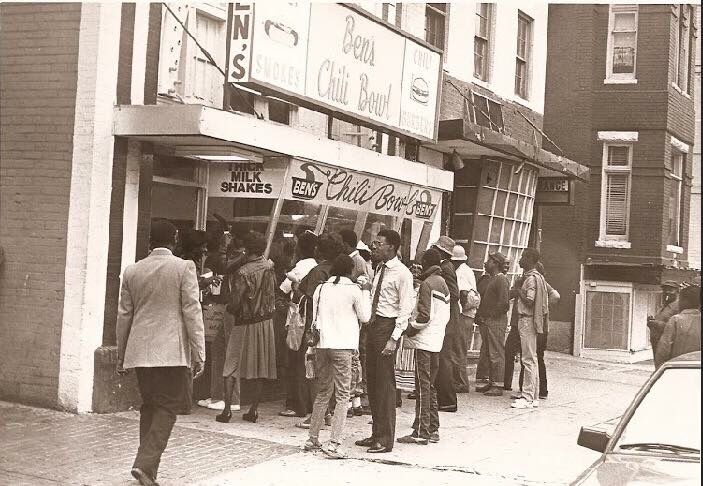

Many things have changed since 1963’s March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom — but not the chili half-smokes at Ben’s Chili Bowl on U Street NW, nor the resolve and recollections of owner Virginia Ali.

On Friday, thousands are expected in the nation’s capital to participate in a march against police brutality. The march — organized by the Rev. Al Sharpton — comes nearly three months after nationwide protests sparked by the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis and amid continued coronavirus restrictions.

Weeks before the Aug. 28, 1963 event, Ali learned of the march from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., whose “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial was a highlight of the event, drawing an estimated 250,000 people from across the country.

”Dr. King had a satellite office just up the street from Ben’s, at 14th and U. So, he would pop in from time to time,” said Ali, who opened the restaurant with her late husband, Ben, in 1958.

“When he was visiting, he would talk to us about his dream, and he told me about the upcoming march,” she said.

Some civil rights protests had turned violent earlier that year, with white people and law enforcement clashing with nonviolent demonstrators.

”As the day approached, and we were seeing things happening in the South, we were a little bit nervous,” Ali recalled. “There had been unrest in the South, and we didn’t want anything to happen that would [negatively] affect the movement.”

The stakes were high.

”Even President Kennedy had said to the leaders of the march that if all these people came to town and there was any kind of disruption, that would set the movement back,” Ali said.

In 1963, the Ali family’s restaurant was already a gathering spot “on our Black Broadway.” Despite segregation in the early 20th century, U Street NW was a thriving cultural center for Blacks, with theaters featuring top performers.

In the days leading up to the march, Ben’s Chili Bowl fed people arriving in D.C.

Virginia and Ben Ali weren’t about to miss the event at the Lincoln Memorial on Aug. 28, 1963.

”I remember we dashed to the Lincoln. We took the bus as far as we could go, and then we walked a long way. It was so crowded,” she said.

Even before King spoke, Ali said the huge gathering was moving and inspirational.

“Everybody was in a great mood, and they were well-dressed. It was wonderful,” Ali said. “I don’t think we thought we were making history, but we were there for a purpose.”

Martin Luther King Jr. addressed the crowd near the end of the program with an undersized public address system.

”We heard enough of it to feel ecstatic about the speech. Certainly, it had a bigger impact when we could hear it clearly, in our own home and on the radio,”

That evening, Ali remembered a feeling of joy, hope and determination on U Street, as those who had been at the march stopped by Ben’s Chili Bowl to eat and revel.

Fifty-seven years later, Ali said she is glad to welcome visitors and participants to Ben’s, before and after Friday’s march.

”You know, it’s very sad to think that we are having to even do this again,” Ali said. “But we have so many issues to deal with this time — we’ve got the police brutality thing going on; we’ve got division in the country; we need education for everybody.”

Ali notes a difference between the civil rights protests in 1963 and today. The 1963 event was organized by several adult leaders, including King, A. Philip Randolph, Whitney Young Jr., James Farmer, Roy Wilkins and John Lewis. Bayard Rustin was the chief organizer.

“Back then we had strong leaders, which was wonderful. Today, we’ve got young people, coming out on their very own because they feel so strongly about what’s going on in this country.”

As in 1963, Ali believes most of the protesters are following examples set by King.

“There are some instigators out there that would not like this to go well, and they’re the problem,” Ali said. “But the protesters that are out there for the reason of systemic change in this country are nonviolent.”

King was assassinated in 1968, prompting the riots on U Street.

Ali is encouraged by the civic mindedness and political activism in the middle of the protests against systemic racism and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since Ben’s Chili Bowl has been an instrumental touchstone in the community for 62 years, Ali hopes D.C. will include the restaurant as one of its mail ballot drop box locations.

To lessen the risk of coronavirus spread at indoor polling locations, the D.C. Board of Elections has chosen drop sites throughout the District, where voters can deposit a completed mail ballot before 8 p.m. on Election Day on Nov. 3, 2020.